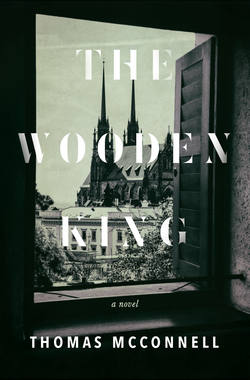

Читать книгу The Wooden King - Thomas Maxwell McConnell - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление15 MARCH 1939

They came through the snow, trucks of infantry, motorcycles with men in trench coats riding the sidecars, platoons by bicycle hurling back the barriers at the frontiers for half-tracks, a few tanks, armored cars. A dress rehearsal for Poland six months later. Hitler himself came in the secure evening and the next day processed through the cities in his bullet-proof Mercedes. In the clamorous squares children peeked out from forests of legs to glimpse him, to wave little red flags with broken crosses while their cheering parents among the German minority gave the salute. The Ides of March, 1939. Their infamous day.

In Munich the fall before, Chamberlain and Daladier had cast the die, assigned to Hitler all he needed to render the country indefensible. Across the table the statesmen shook hands over the dissected map of what had been Czechoslovakia. No Czech was in the room while their nation was dismembered. Hungary hacked away a whole province. Poland gouged its portion. Slovakia was amputated into independence but might as well have been kept in a jar in Berlin.

So under a March snow their republic melted into the haze of the past and a new word came into the language for Hitler’s man in the castle: Reichsprotektor. A new word for the land he ruled: Protektorate. Czechs had known twenty years as a free people since that day in Philadelphia at the end of the Great War when their liberator, their first president, Thomas Masaryk, had declared their birth in a street beside Independence Hall. For the rest of his life Masaryk reasoned with his countrymen, goaded them together toward middle Europe’s first democracy until, exhausted at eighty-seven, he died when they needed his wisdom most. He was spared the fate of his country as his two successors were not. The bookish one, Benes, resigned after the disaster at Munich and went into exile. The old judge, Hacha, the last alternative, a grandfather doting on senility, collapsed across a carpet in Hitler’s chancellery the night of the invasion. He had to be revived with an injection so he could sign the death warrant for the corpse that remained. And the assassination was complete.

What the people inherited was the gun and the Gestapo, the parading field gray of the Wehrmacht and thugs on the corners. Jews lost their jobs. The universities, except the ones for Germans, were closed. The blackouts began and the whispering. Schools became jails, the palaces of Bohemian kings became prisons, beams in their cellars hung with nooses of wire. So the people waited in line for black bread and bits of meat, for the will to go on and whatever the gods of fate or the lords of war would bring them.

Watching the great wet flakes descend on the eve of spring they parted their lace curtains with almost steady hands and looked out at the boots and tires splashing through their streets. Breaths misting on the pane, they murmured to one another, “It’s bad.”