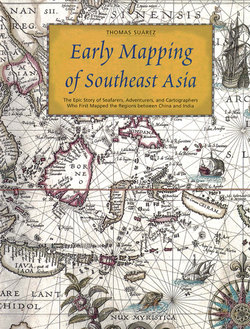

Читать книгу Early Mapping of Southeast Asia - Thomas Suarez - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 4

Asia and Classical Europe

Of the various peoples inhabiting Europe in ancient times, only the dominant Greek and Roman civilizations were in a position to seriously consider who and what lay far to their east. It is doubtful if those who lived in western and northern Europe, whatever their sophistication and aspirations, learned anything about the East which had not been sifted through those Mediterranean powers.

Greece

The earliest known cartographic allusion in Greek civilization, is the so-called 'shield of Achilles' from the Iliad of Homer (before 700 B.C.). This was a cosmological device not intended to show specific geographic features; neither Asia as an entity, or even the divisions of the continents, were reflected in this view. Achilles' shield depicted a 'River Ocean' surrounding the cosmological whole, which foreshadowed the idea of an ocean sea encircling the continenral land. The enrire earth, as well as the seas, sun, moon and stars, all formed part of the center of the disk. True geographic divisions were drawn in the sixth century B.C. by Anaximander, a theoretician who, like Homer, lived in what is now Turkey. The Greek world, itself blessed with a wealth of islands, probably envisioned islands dotting much of the ocean sea.

The Name 'Asia'

'Asia' is an ancient name. In the fifth century B.C., Herodotus was already speculating about its origin, noting that most Greeks believed the continent to have been named after the wife of Prometheus. Other accounrs describe Asia as the mother, by Iapetus, of Atlas, Prometheus, and Epimetheus. In any event, Asia was an Oceanid, a sea-nymph daughter of Oceanus and Tethys, similar to a Nereid.

Greek Excursions to the East

In about 513 B.C., the region of the Indus valley was taken by Darius of Persia. A Greek officer, Scylax of Caryanda, was sent into the newly-acquired territory, sailing much of the Indus River and helping to push the Persian − and ultimately the Greek − world view eastward into Asia. Scylax, however, reponed that the Indus flowed to the southeast, an error that, as we shall see, helped stunt even a hypothetical expansion of the continent farther east (although segments of the river do indeed flow to the southeast, the overall orientation is flowing to the southwest). Scylax also initiated the durable tradition of concocting strange quasi-human inhabitants for the Orient, such as the people whose feet are so large that they use them as umbrellas.

The ancient world never reached any consensus regarding the extent of Asia. About 500 B.C., Hecataeus of Miletus espoused the notion of a disc-shaped earth with Asia and Europe of roughly equal size. Herodotus (ca. 484-425 B.C.), remembered fondly as the 'father of history', argued instead that Europe was larger than Asia, and questioned whether the inhabited world was entirely surrounded by water. "I cannot help laughing," Herodotus mused, "at the absurdity of all the map makers- there were plenty of them -who show Ocean running like a river round a perfectly circular earth, with Asia and Europe of the same size." He believed Europe robe as large as Asia and Africa combined. Among his early critics was Ctesias of Cnidus (ca. 400 B.C.); whereas Herodotus vastly understated the size of Asia, Ctesias exaggerated it.

A proponent of experience-founded empirical geography, Herodotus reviewed a great number of writings and reports about Asia. In his opinion, ''Asia is inhabited as far as India; further east the country is uninhabited, and nobody knows what it is like." He dismisses reports furnished by his countryman Aristaeus95 of the sundry people said to live far across Asia, flatly stating that "eastward of India lies [an uninhabitable] desert of sand; indeed, of all the inhabitants of Asia of whom we have any reliable information, the Indians are the most easterly."

Alexander the Great

Thus by the time Alexander the Great (356-323 B.C.) pushed eastward in his attempt to conquer the world, Greek civilization had diverse ideas regarding the eastern end of the world. Some of Alexander's soldiers probably believed that they would need only to subdue India before meeting the ocean sea which ringed the earth. But Alexander had been tutored by the great philosopher Aristotle (384-322 B.C.), who postulated a vast Asian continent, extending much farther to the east than Alexander's exploits. Aristotle believed that the circumference of the earth was 400,000 stades, which exceeded the correct figure by at least 50 percent, and that the expanse of sea separating the eastern shores of 'India' from Spain was not great. Thus he envisioned the Asian continent extending through, and well beyond, our Southeast Asia. Alexander never learned for himself what lay past the Indus, since his troops refused to advance past the river. "Those who accompanied Alexander the Great," noted Pliny in the first century A.D., "have written... that India comprises a third of the whole land surface of the world and that its populations are uncountable."

Alexander's conquests, and his decision to split his people into three segments for a return via inland, coastal, and ocean routes, greatly expanded Greek knowledge of the East and of the western Indian Ocean region. With his conquests began regular trade in India's ivory and spices. Despite Alexander the Great's failure to reach Southeast Asia, two thousand years later some 'credible' European writers would claim that the extraordinary Cambodian edifices at Angkor were built by him.96 As absurd as such an assertion was, it would lend legitimacy to European designs on Southeast Asian soil.

Following the death of Alexander, the various factions of the Greek empire fell into ruinous warfare among themselves, dampening any energy for exploits into India until Seleucus Nikator consolidated power in about 300 B.C. Seleucus, realizing that he could not overpower the Maurya rulers east of the Indus, instead negotiated safe passage for an ambassador named Megasthenes to cross India to the Maurya court in Pãtaliputra (Patna), along the valley of the Ganges. Megasthenes was, indeed, on the frontier of 'India beyond the Ganges', Southeast Asia. His account of India, Indica, was the paramount Greek record of 'eastern' Asia. It was Europe's first notice of Ceylon, of Tibet, of the origin of the Ganges in the Himalayas, the shape of the Indian subcontinent, and of the monsoons, that great natural engine which would facilitate travel across the Indian Ocean.

The various reports gained from Alexander's exploits and Megasthenes' embassy were examined by Eratosthenes (ca. 276-ca.196 B.C.), a brilliant librarian at Alexandria, born about a half century after Alexander's death. Eratosthenes, who is best remembered for having calculated an uncannily accurate figure for the earth's circumference, learned of Ceylon and the peninsular nature of India from Megasthenes' reports.

But Eratosthenes, perhaps extrapolating from the erroneous southeasterly flow of the Indus assigned by Scylax, concluded that the Indian subcontinent was oriented to the southeast, leading him and his contemporaries to believe that India formed the southeastern threshold of the Asian continent. It is true, of course, that the Ganges River was now known, suggesting that 'India beyond the Ganges', our Southeast Asia, was there by implication, since something obviously had to form the eastern banks of the Ganges. But the Ganges was instead adapted to fit the existing world view, flowing to the east into the ocean sea rather than south into the Indian Ocean. As a result of their misconceptions, 'beyond the Ganges' meant north of the Ganges. In the mid-sixteenth century Gerard Mercator, under entirely different circumstances and for unrelated reasons, reached the same conclusion, deciding that the Ganges was in reality the Canton River in southern China (see page 101, below).

With the decline of the Greek empire, Greek civilization and the Hellenic world effectively lost touch with the world east of the Hindu Kush mountain range in Central Asia, dampening any dreams of further expansion. Intermediaries seized the opportunity for trade, and Indian merchants may have reached Alexandria directly by the second century B.C. In 146 B.C., the remnants of the Greek states were effectively subjugated by the next emerging European superpower, Rome.

Rome

Contact between Rome and entrepôts far to the east is recorded in 26 B.C., in which year Augustus received envoys from Sri Lanka. A white elephant exhibited in Rome during Augustus' time may have originated in Southeast Asia, in the general region of what is now Thailand (the 'white' elephant in this case was probably an albino animal rather than the so-called 'white elephant' which is revered in Siam and Burma- the latter is identified by a number of physical traits, of which color is of relatively minor importance).97 In about 166 A.D., a group of Roman musicians and acrobats traveled to China via Burma; a Roman lamp dating from this era has been unearthed in P'ong Tük, on the northeast part of the Malay Peninsula, along what may have then been a trans-peninsular shortcut.98

Hippalus

The consolidation of the Roman Empire helped circumvent many of the middle-traders who had come into the Indian trade after Alexander. But until the very early Christian era, Mediterranean merchants had either to rely on the monopoly of traders in southwestern Arabia, or sail the lengthy, dangerous route along the coast of Persia and the Arabian Sea. This limitation, however, was broken in the middle of the first century, when a Greek sailor named Hippalus revealed one of nature's great secrets: Hippalus learned how to harness the seasonal winds.

Hippalus determined that the prevailing winds in the Indian Ocean reversed direction seasonally, and thereby theorized that one could sail to India via open ocean, out of sight of land, and return when the winds reversed. In about 45 A.D., he successfully sailed from the mouth of the Red Sea to the delta of the Indus River, and thence to ports along the Malabar Coast. The spring and summer monsoons upon which he had gambled then safely returned his vessel, now filled with Indian goods, to Egypt. A record of his voyage was preserved in the writings of the Roman historian Pliny, as well as in an anonymous document written in the first century, the Periplus of the Erythrean Sea, (i.e., Indian Ocean), a guide for mariners wishing to trade with India.

Both the Peripfus and Pliny helped relay the new reports about India. The Peri plus described the coasts from the Indus to the Ganges delta, as well as information about Sri Lanka based on secondary sources. Pliny records information clearly based on actual navigation of the waters east of India, noting that "the sea between Taprobana [Sri Lanka] and the Indian mainland is shallow, not more than 18 feet deep, but in certain channels the depth is such that no anchors can rest on the sea-bed." He also noted the voyage to Ceylon from Prasii being made in seven days "in boats built of papyrus and with the kind of rigging employed in the Nile."

The new sailing method brought India much closer to Europe and the Mediterranean, and this, in turn, brought Southeast Asia that much closer as well. With Roman sailors frequenting the eastern coast of India by the second century A.D., Asian commodities were reaching the Mediterranean world in generous quantities, silks generally coming by land via Antioch (Syria), and spices by sea via Alexandria. Merchandise being sent on to Italy was generally shipped to Pozzuoli, near Naples.

Though profit rather than knowledge was the driving force (Pliny remarking that "India is brought near by lust for gain"), more extensive commerce provided new channels through which geographers could enrich their storehouse of data. The fact that products from eastern Asia reached Rome meant that ideas, information, and perhaps even geographic data, could make that journey as well.

The range of marketable Asian goods increased as well. Diverse commodities were imported, from 'exotic' Asian animals to asbestos (used for oil lamp wicks) and slave women- a far greater range of valuables than just silks and spices. An ivory statue of an Indian goddess of fortune, Lakshmi, unearthed in the twentieth century in the remains of Pompeii, was clearly acquired before the city was buried by Vesuvius in 79 A.D. Chinese earthenware and bronzes have been excavated in Roman cities, and Roman traders appear to have reached China in the second and third centuries A.D. Roman coins, directly or indirectly, reached the kingdom of Funan in the Mekong River delta as early as the second century.

In our day of cheap, plentiful spices, it is difficult to imagine the fuss made about spice-producing regions in ancient times, and indeed up until relatively recent times. Two thousand years ago, Pliny wondered similarly:

It is amazing that pepper is so popular. Some substances attract by their sweetness, others by their appearance, yet pepper has neither fruit nor berries to commend it. Its only attraction is its bitter flavor, and to think that we travel to India for it! Both pepper and ginger grow wild in their own countries, yet they are purchased by weight as if they were gold and silver.

Chryse and Argyre

Gold and silver, in fact, characterize the earliest extant specific Western reference to Southeast Asia. Pomponius Mela (fl. 37-43 A.D.), a Roman geographer and native of southern Spain, largely carried on the Greek tradition about the East, perpetuating stories about Amazons, people without heads, griffins, and other such characters, but adds two lands which lay to the east of India. One was Chryse, said to boast soil of gold, the other Argyre, said to have soil of silver:

In the vicinity of Tamus is the island of Chryse; in the vicinity of the Ganges that of Argyre. According to olden writers, the soil of the former consists of gold, that of the latter is of silver and it seems very probable that either the name arises from this fact or the legend derives from the name.

Mela was quoting earlier, unknown sources and he goes on to vaguely menrion the possibility of a Southeast Asian peninsula:

Between Colis [southeastern tip of Asia] and Tamus [China'] the coast runs straight. It is inhabited by retiring peoples who garner rich harvests from the sea.

Pliny also alludes to a Southeast Asian peninsula. Noting that the Seres [Chinese) wait for trade to come to them, he lists three rivers of China, which are followed by "the promontory of Chryse", and then a bay. Elsewhere in his Natural History, however, Pliny refers to Chryse as an island. The discrepancy probably results from his having compiled news of the 'land of gold' from contact via land (peninsula) and sea (island). It was more often mapped as an island in medieval mappaemundi.

Fig 29. World map after Strabo/Mela. An anonymous sixteenth century manuscript. (30.5 x 43.5 cm) [Sidney R. Knafel]

Fig. 30 The 'Turin' world map, twelfth century. Of the two islands in the ocean sea immediately above Adam and Eve, the righthand one represents the Southeast Asian realms of Argyre and Chryse. Reproduced from the facsimile in Nordenskiold, Facsimile Atlas, Stockholm, 1889.

Fig. 31 'Turin' world map (detail). Adam and Eve, the Serpent and the island of Chryse and Argyre.

Chryse most likely represented Malaya, while Argyre was probably Burma, perhaps Arakan. Both are seen as islands in the world map after Mela (fig. 9), Chryse being the island off the east Asian coast, and Argyre the island at the Ganges delta next to Taprobana. On the twelfth-century 'Turin' world map (figs. 30 & 31), they appear as a single island in the easternmost ocean sea, the right-hand isle of the two immediately above Adam and Eve (the left-hand isle is simply designated insula, and thus may have been intended for either Chryse or Argyre).

Mention of Chryse is also made in the Periplus of the Erythrean Sea, which describes Chryse as "the last part of the inhabited world toward the east, under the rising sun itself, " a land from which comes "the best tortoise-shell of all the places on the Erythr;can Sea." The work's anonymous author then described the land of This (China) and city of Thint£, from which raw silk, silk yarn, and silk cloth, acquired through silent barter, were brought overland to India.99 Isidorus Hispalensis (Isidore of Seville, ca. 560-636 A.D.), in his Etymologiae, one of the most popular cosmographies of the Middle Ages, also placed the lands of Chryse and Argyre in the southeastern extreme of the world, along with Taprobana and Tyle (Tile, an island near India).

Interestingly, Chryse and Argyre are reminiscent of some aspects of Buddhist cosmology where the waters that pour forth from Sumeru flow into four canals separated by four mountains, of which one is gold, another silver, and theother two, precious stones and crystal.100 The image of four canals separating four landmasses, can also be compared with a view of the Arctic region found in a medieval European text and used in later world maps by the Renaissance cartographers Ruysch (1507, fig. 56), Fine (1 531, fig.48) and Mercator (1569).

The search for gold also promoted intra-Asian maritime trade in the Indian Ocean during the first century A.D. As a result of the disruption by internal disorders of the traditional routes through the steppes of Central Asia to Siberian gold reserves, new sources for the metal, a medium of exchange between various Asian peoples, were sought. Rome decreased the gold content of its coins and introduced measures to halt their exportation. At the same time, new ocean-going vessels and navigational techniques made it more feasible for Indian merchants to pursue the 'Islands of Gold' to their east.

The association of Southeast Asia with gold was so strong that Josephus, in his Antiquities of the jews (second half of the first century), wrote that Ophir, the land from which King Solomon had fetched gold, is now known as Aurea Chersonesus (Golden Peninsula, i.e. Malaya). Josephus thus began the recurring idea that the Ophir of the Bible was in Southeast Asia, a belief that can be found in earnest through the latter nineteenth century. Various places were believed to have been the site of Ophir, from Malaya to Indochina, Sumatra, and the Pacific Ocean.

Marinus and Ptolemy

At about the same time as Josephus, a 'Golden Peninsula' in Southeast Asia was described by a geographer from Tyre by the name of Marin us. Tyre lies on the eastern Mediterranean coast, in what is now Lebanon. Today it is a peninsula, but in ancient times it was an island blessed with two bustling ports. Tyre had been the capital of Phoenicia from the eleventh to sixth centuries B.C., but was captured by Alexander in the fourth century B.C. It subsequently came under the control of Rome, remaining in Roman hands until the seventh century A.D. Tyre was ideally situated for gathering information about the East from traders and seafarers, and Marinus used his city's advantageous location to expand the world map from their reports.