Читать книгу Posters for Peace - Thomas W. Benson - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

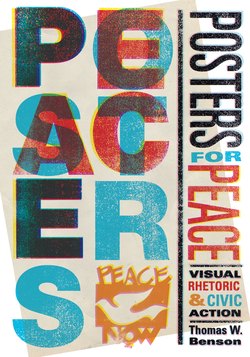

ОглавлениеPOSTERS FOR PEACE

Visual Rhetoric and Civic Action

FIGURE 1 “Peace Now.” Berkeley, California, 1970. Thomas W. Benson Political Protest Collection, Historical Collections and Labor Archives, Eberly Family Special Collections Library, University Libraries, The Pennsylvania State University.

This book is an account of the visual rhetoric of a collection of peace posters created in Berkeley, California, in 1970, and of the circumstances in which they were brought into being and given meaning. The posters themselves were a small but telling part of an energetic and diverse movement by American college students in the 1960s and early 1970s against war and racism. Student activism in the United States in the 1960s was part of a loosely connected worldwide movement that took on different forms—most memorably, perhaps, in 1968. The events of May 1970 brought a terrible climax to a long period of confusion and turmoil.

Posters for Peace begins with an extended essay on the rhetorical history of the posters and their immediate and longer-term historical context. It offers close readings of the posters from a rhetorical perspective, with comparisons to other visual examples where appropriate, and with annotations to explain some of the posters’ multiple cultural meanings. The rhetorical approach attempted here regards the posters as addressed to viewers—in this case, by unknown artists to unspecified audiences—and it explores their antecedents, contexts, and forms. Through close reading and comparative analysis, this approach attempts to recover and reimagine the potential experiences invited by the posters as rhetoric. The second section of the book presents a gallery of the Berkeley posters in the Protest Posters Collection at the Penn State University Libraries. The posters themselves are now owned by the Historical Collections and Labor Archives in the Eberly Family Special Collections Library. A condition of their gift to Penn State was that they should be freely available for nonprofit educational uses. They are also available online at the library and at the Flickr Creative Commons.1

The close-reading approach is an attempt to recover how the posters might have looked in 1970. This is partly an exercise in recovery—recovery of the meanings that might have been invited by and achieved by these posters in 1970—but also reflects an understanding that the posters are of interest as part of the continuing conversation of American culture. Recovering the meanings that might have been circulating in 1970 is not simply an exercise in taxidermy, the recovery of an inert and bygone moment. Our own historical and political context may distort our capacity to recover the posters’ rhetoric as it existed in 1970. And yet, a reader of this book might very well want to look at these posters precisely to make use of them. Understanding something more about them as part of a context will perhaps make that recovery more useful.

The close reading of visual rhetoric begins by attending to the primary, manifest verbal and visual content, as well as the primary stylistic features—color, form, line, and so on. Comparative, inventional, and audience perspectives guide the analysis. A comparative approach, when undertaken from a rhetorical perspective, as in this study, has multiple, overlapping dimensions. The posters’ direct appeal stems from their location within the larger rhetorical currents of the time—both the “moment” of May 1970 and the broader political and cultural rhetorics of the long 1960s. A comparative approach to the posters as visual rhetoric seeks to invite the reader to view the posters in context and in contrast to earlier and later visual rhetorics that may or may not have been accessible to the artists and audiences of the posters in 1970; such an approach helps us to see what contemporaries probably took for granted, things seen but not explicitly noticed by artists and audiences in 1970. A study of the pre-1970 history of the poster and of political graphics may provide clues into what may be called the inventional rhetoric of the posters—that is, the resources, traditions, and rhetorical iconographies that the poster artists may have consulted, directly or indirectly, as they created the images considered here. A parallel comparative approach attempts to reconstruct what might be called the rhetoric of reception, which takes into account the resources of those who viewed and perhaps recirculated the posters in 1970. These three comparative approaches—of the poster artist, of the 1970 poster viewer, and of the reader who comes upon the posters decades later and seeks to recover them for the present—are not entirely exclusive, but they are conceptually different. In any case, the close readings and the comparisons are undertaken from a rhetorical perspective—this study seeks to understand the posters not primarily as part of the history of art but as works of visual rhetoric and civic persuasion.

The study of rhetoric was itself at a transformative moment in 1970, and that transformation is part of the story I attempt to tell in these pages. In May 1970, the month these posters were circulating in Berkeley, a group of scholars came together in the National Developmental Project in Rhetoric. The 1960s campus politics of civil liberties, civil rights, and peace helped to prompt a redirection and renewal of rhetorical studies; those changes in rhetorical studies, especially the development of studies in visual rhetoric, provide some of the grounding of the present study, and they may be seen as one example of how the 1960s prompted transformations in disciplines across the humanities and social sciences.

In 1970 some art historians would have argued that these posters were mere illustration or graphic design, but not art. Similarly, some rhetorical scholars would have argued that posters were not rhetoric in the full sense of the term—some scholars and gatekeepers saw “rhetoric” as being limited to persuasive verbal discourse, or even more narrowly to public oratory. In this study, I do not ask whether the posters are art or rhetoric (or even whether they are neither). Instead, I assume they are at least in some sense both, and I inquire into how they played their part in the politics of 1970. “Posters,” writes Jeffrey T. Schnapp, “provide a literal, material bridge between the new public sphere constituted by mass communications and the public spaces that become the sites of modern politics as street theater.”2 For decades, posters had been employed as agencies of state propaganda and popular protest. In The Power of the Poster, Margaret Timmers notes, “By its nature, the poster has the ability to seize the immediate attention of the viewer, and then to retain it for what is usually a brief but intense period. During that span of attention, it can provoke and motivate its audience—it can make the viewer gasp, laugh, reflect, question, assent, protest, recoil, or otherwise react. This is part of the process by which the message is conveyed and, in successful cases, ultimately acted upon. At its most effective, the poster is a dynamic force for change.”3 So familiar are we with the poster as a rhetorical object that when we notice a poster we instantly understand that it is asking something of us—or of someone. Posters, as they exist in our vernacular cultural experience, are fundamentally rhetorical. In Berkeley, California, in May 1970, student protesters used posters to mobilize citizens for continuing opposition to the Vietnam War in the name of enduring American ideals.

A Time to Kill, and a Time to Heal

On the evening of April 30, 1970, President Richard Nixon addressed the country on national television, announcing that US forces were entering Cambodia—an incursion that would expand the Vietnam War (see fig. 2). He said, in part,

FIGURE 2 Richard Nixon, Cambodia Address, April 30, 1970. Photograph by Jack E. Kightlinger. White House Photo Office, WHPO 3448–21A. Courtesy Richard Nixon Library, National Archives and Records Administration.

Tonight, American and South Vietnamese units will attack the headquarters for the entire Communist military operation in South Vietnam. This key control center has been occupied by the North Vietnamese and Vietcong for five years in blatant violation of Cambodia’s neutrality.

This is not an invasion of Cambodia. The areas in which these attacks will be launched are completely occupied and controlled by North Vietnamese forces. Our purpose is not to occupy the areas. Once enemy forces are driven out of these sanctuaries, and once their military supplies are destroyed, we will withdraw.

Nixon acknowledged that the American people wanted to see an end to the war, but he appealed for support for an invasion that he described as part of a plan that would allow the United States to withdraw from Vietnam. He issued a warning to those people, especially student radicals, opposing his program: “My fellow Americans, we live in an age of anarchy, both abroad and at home. We see mindless attacks on all the great institutions which have been created by free civilizations in the last 500 years. Even here in the United States, great universities are being systematically destroyed.”4 Despite Nixon’s attempt to portray the Cambodian adventure as merely an “incursion” by the armed forces of South Vietnam, the growing opposition to the president’s Vietnam policies in Congress and among the press strongly denounced the action as an illegal US invasion of Cambodia.5

Senator Charles Goodell, a Republican from New York who had been appointed to fill the unexpired term of the assassinated Robert F. Kennedy in 1968, introduced a resolution of impeachment. Two days after Nixon’s speech, James Reston wrote in the New York Times that “it is a thunderingly silly argument to suggest [as Nixon had] that wiping out the enemy’s bases in Cambodia will get to ‘the heart of the trouble.’” Reston argued that “as a television show and a political exercise it [the speech] may have been effective, but as a serious Presidential presentation of the brutal facts of a tragic and dangerous problem of world politics, it was ridiculous.”6

By 1970 student opposition to the war had become widespread, and the Cambodian invasion stimulated protests across the country. In some cases, ROTC buildings on campuses were destroyed, although it was not always clear whether students were responsible.7 Student leaders called for a national student strike against the war. It is difficult now to recall how unsteady the United States seemed to be in those days. Watergate, with all of its dislocations, was still ahead, but in less than ten years America had witnessed the murders of President John F. Kennedy and his brother, Robert, and African American leaders Malcolm X, Medgar Evers, and Martin Luther King Jr. Police attacked dissidents in Chicago for the 1968 Democratic National Convention in what official reports later called a police riot, and rioters torched America’s inner cities. Analysts wrote of “student unrest” and “civil disturbances,” and wondered whether history itself was broken.

President Nixon and other national politicians stoked resentment against the students. On May 1, the day after his Cambodia address, Nixon visited the Pentagon for a military briefing and stopped to speak with a group of civilian employees. A woman in the group told Nixon, “I loved your speech. It made me proud to be an American.” A New York Times reporter recounts the incident:

Smiling and obviously pleased, Mr. Nixon stopped and told how he had been thinking, as he wrote his speech, about “those kids out there [in Vietnam].”

“I have seen them. They are the greatest,” he said. Then he contrasted them with antiwar activists on university campuses. According to a White House text of his remarks, he said:

“You see these bums, you know, blowing up the campuses. Listen, the boys that are on the college campuses today are the luckiest people in the world, going to the greatest universities, and here they are burning up the books, storming around about this issue. You name it. Get rid of the war there will be another one.”

The Times reporter wrote, “The President’s use of the term ‘bums’ to refer to student radicals was the strongest language he has used publicly on the subject of campus violence, although he has been known to employ such terms in private.”8

On May 2, the Army ROTC building at Kent State University in Ohio was burned down during a student antiwar demonstration. The circumstances were suspicious enough that serious observers speculated the fire might have been part of a scenario of provocation by police or other government agents.9 On Sunday, May 3, Ohio governor James Rhodes, a Republican who was trailing in his Senate primary campaign, took advantage of the situation to visit Kent State, where he vowed to keep the university open despite the advice of others that closing it for a time would allow things to calm down. Rhodes held a news conference, warning,

The scene here that the city of Kent is facing is probably the most vicious form of campus-oriented violence yet perpetrated by dissident groups and their allies in the State of Ohio. . . . We’re going to use every weapon of law enforcement agencies of Ohio to drive them out of Kent. . . . They’re worse than the brownshirts and the Communist element and also the night riders and the vigilantes. They’re the worst type of people that we harbor in America. . . . We are going to eradicate the problem, we’re not going to treat the symptoms.10

Asked by reporters what the governor’s remarks meant for the National Guard, “General Del Corso clarified it for the newsmen. ‘As the Ohio law says,’ the general pointed out, ‘use any force that’s necessary even to the point of shooting. We don’t want to get into that, but the law says we can if necessary.’”11

The next day they did. After chasing students, including many who were simply walking to class, across the Kent State campus, the National Guard slashed several students with bayonets and later fired at students who presented no immediate threat to the Guard or others. Four students were killed. Nine were wounded by gunfire.

The events at Kent State intensified campus protests across the nation. After Nixon’s Cambodia speech, many university presidents shut down their campuses for short periods or for the rest of the academic year—Columbia University was closed from May 2, and some other campuses followed after Kent State. Student strikes and demonstrations spread rapidly.

Nixon supported the National Guard while implicitly disclaiming responsibility for the massacre. At the regular White House news briefing on May 4, press secretary Ronald Ziegler read a statement from the president: “This should remind us all once again that when dissent turns to violence, it invites tragedy. It is my hope that this tragic and unfortunate incident will strengthen the determination of all the Nation’s campuses—administration, faculty, and students alike—to stand firmly for the right which exists in this country of peaceful dissent and just as strongly against the resort to violence as a means of such expression.”12 Nixon’s rhetoric in this statement is peculiar—the only active agents to whom he alludes are “administration, faculty, and students,” who appear to be responsible for inviting tragedy. The National Guard and Nixon himself disappear into the passive voice. But the president also professed his good intentions.

In New York City on May 8, construction workers using crowbars, other tools, and hard hats attacked an antiwar rally on Wall Street held in honor of the Kent State victims. Seventy people were injured. The mayhem spread to City Hall, where an American flag flew at half staff to commemorate the Kent State students: the construction workers demanded that it be raised to full staff. Other rioters attacked the nearby Trinity Episcopal Church, tearing down its flag and a Red Cross banner.13 It was rhetorically convenient for the Nixon administration and its supporters to depict resistance to the Vietnam War as limited to radical, privileged college students, and this depiction has survived in collective memory. And yet many working-class Americans opposed the war, and the draft, and resistance to the war could be found in all ranks of society and in the military.14

At his evening news conference on May 8, President Nixon was asked repeatedly about student dissent and his administration’s reaction to it. Herbert Kaplow of NBC News questioned the president about what he thought the students were trying to say. Nixon replied, “They are trying to say they want peace. They are trying to say they want to stop the killing. They are trying to say that they want to end the draft. They are trying to say that we ought to get out of Vietnam. I agree with everything that they are trying to accomplish.”15 At five o’clock the next morning, President Nixon, accompanied by his valet, Manolo Sanchez, traveled to the Lincoln Memorial for an unplanned predawn conversation with fifty or so students who were in town for antiwar protests. In his Vietnam: A History, Stanley Karnow wrote that Nixon “treated them to a clumsy and condescending monologue, which he made public in an awkward attempt to display his benevolence.”16 Soon afterward, in actions that led directly to Watergate and the fall of his presidency, Nixon “ordered the formation of a covert team headed by Tom Huston, a former Army intelligence specialist, to improve the surveillance of domestic critics. During later investigations into Nixon’s alleged violations of the law, Senator Sam Ervin of North Carolina called the Huston project evidence of a ‘Gestapo mentality,’ and Huston himself warned Nixon that the internal espionage was illicit.”17

Shortly after midnight on May 15, 1970, on the campus of Jackson State University in Jackson, Mississippi, city and state police fired at a group of protesting students. Two students, one from Jackson State and the other a local high school student, were killed; twelve others were struck by gunfire. President Nixon expressed his regrets and continued his public campaign for support of his war policies. At the end of May, he appeared at a Billy Graham revival for a photo opportunity. Meanwhile, student protests continued around the country.

At the Berkeley campus of the University of California, political protest had been intense since the day after Nixon’s Cambodia speech. Berkeley had been the scene of student political activity since at least 1958, when some student leaders founded SLATE, a loose confederation of progressive students, both graduate and undergraduate, to run as a united ticket in student-government elections. The administration had responded by removing graduate students from the student-government elections and by taking other actions to impede student political action. In 1960, the House Un-American Activities Committee held hearings at City Hall in San Francisco. Students from around the Bay Area picketed the hearings to protest that the committee was an enemy of civil liberties. Police with fire hoses attacked them and dragged them down the long flight of marble steps at the center of the City Hall rotunda, hauling the protesters away in paddy wagons.

As the civil rights movement gained momentum, especially after the sit-ins of 1960, the Freedom Rides of 1961, and voter registration campaigns in Mississippi, Berkeley students circulated information and collected money on campus and at the traditional cluster of tables at the southern entrance of the university at the intersection of Telegraph and Bancroft. The university responded by declaring new rules prohibiting any campus political activity about anything other than purely university business. These restrictions gave rise to the Free Speech Movement at Berkeley, which played out over the academic year of 1964–65. On October 1, 1964, a former graduate student who was sitting at the CORE table was arrested. The police car was immediately surrounded by hundreds of students. Over the next several days, support for the students grew. These were the demonstrations that made Mario Savio famous nationally.18

In April 1969 a loose coalition of Berkeley residents and students declared the inauguration of what they called People’s Park on a vacant lot that the university had designated for eventual development but which was sitting unused just a short walk south of the university. The People’s Park movement quickly drew the enthusiasm of a diverse group of students, progressives, hippies, and local community activists. The university responded that they had no business being on the site, but then agreed that it would not evict them from the park without further negotiations. At this point, Ronald Reagan, who had been elected governor in 1966 in a campaign partly directed against the Berkeley campus, intervened.

Reagan sent the National Guard—almost 3,000 troops—and a large group of sheriff’s deputies—nearly 800—into Berkeley, where, in May 1969, the deputies shot and killed Berkeley student James Rector, an innocent bystander, with a volley of buckshot. Today a mural at the corner of Haste Street and Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley depicts the moment just after Rector was shot (see fig. 3); this section of the mural is based on a photograph taken on the scene by Kathryn Bigelow that was widely circulated at the time. The first publication of the Bigelow photograph of the dying James Rector appears to have been in the Berkeley Barb, an underground newspaper, in its May 23–29 issue, where it features in a group of photographs that also show armed and uniformed men on the street pointing their weapons at the rooftops.19 The Bigelow photograph does not include the men who were aiming shotguns at the rooftop.20 Others were wounded by buckshot and tear gas that day and in the weeks of the occupation.

FIGURE 3 James Rector mural (detail). Haste Street and Telegraph Avenue, Berkeley, California. Photograph by the author, 2013.

The long history of these events created a student movement of considerable experience and commitment. It also created a long history of distrust between the university administration and the governor’s office, on the one hand, and the student leaders and those who sympathized with them on the other, with the Berkeley faculty distributed across the spectrum of opinion and in the middle. The experience of a campus community, and especially of its students, is in many ways discontinuous, because the students are on campus for only a few years. Not all of the history that it is possible to summarize now would have been entirely accessible to the student body. But this truism can work both ways. The indignation and the organizational skills that had repeatedly sparked into being in the decade before May 1970, both over broad issues such as race and war and over the more local frictions between administrators and students, were partly carried off campus with each graduating class. On the other hand, Berkeley gained a reputation as a center of campus activism, which attracted new recruits and allowed the creation of a large core of committed and experienced organizers. The intensity and visibility of the 1960s protest movement in Berkeley, and the continuing publication of movement news and history in local and national sources, kept the history alive and vivid.

As the new academic year of 1969–70 began, just months after the People’s Park attacks, political activity was in daily evidence on campus, especially antiwar appeals, but the tone was muted for the most part, and politics and the war were clearly not the main interests of most students. Yet the war and the state did intrude.

On November 12, 1969, Seymour Hersh of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch broke the story of the My Lai massacre, which had taken place in March 1968. At the village of My Lai, some 350 to 500 innocents, mostly women, children, and old men, had been killed by US troops: many of the victims were lined up at a ditch and executed. News of My Lai left faculty and students shaken and shocked.21

Governor Reagan continued to campaign against the students. In early fall 1969, he announced plans for a 25 percent budget cut for the University of California. In the spring, he intensified his anti-university campaign. As the story is told by Reagan biographer Lou Cannon, three weeks before President Nixon’s Cambodian invasion was announced, Governor Reagan made a remark that seemed consistent with his actions toward Berkeley. “On April 7, 1970, addressing the California Council of Growers at Yosemite, Reagan was asked about the on-campus tactics of the New Left. ‘If it takes a bloodbath, let’s get it over with,’ Reagan responded. ‘No more appeasement.’”22 Reagan’s remarks were quoted in a widely circulated underground newspaper, the Berkeley Tribe.23

On the Berkeley campus in the days after President Nixon’s Cambodia speech, having heard Reagan’s threatening words and others like them, students tried to thread their way safely to class through roving bands of aggressive deputies and sought to avoid clouds of tear gas, fired sometimes from grenade launchers, other times from hovering helicopters: it seemed as if the governor’s office was at war with the university. This experience on the campus went on, day after day, and with special intensity after Nixon’s Cambodia speech.

At Berkeley and many other universities and colleges, demonstrations and strikes were called. When, after the Kent State killings on May 4, several college presidents shut down their institutions for the rest of the academic year, students at Berkeley, instead of declaring a boycott or simply going home, adopted the slogan “On Strike—Keep It Open.” They in effect declared a campus-wide teach-in, asserting and identifying with the ongoing value of the university’s core educational mission. Student and faculty activity persisted even after Governor Reagan ordered the campus shut down for the remainder of the week after Kent State.24 Some classes were canceled, and some students went home. Other classes continued to meet, in some cases revising their agendas to address the current emergency. At least one class was canceled when the teacher and students arrived to find that a tear gas grenade had been thrown through a closed window into the classroom shortly before. There were daily rallies in Sproul Plaza.

Be Young and Shut Up

Some yards east of Sproul Plaza and up the hill is Wurster Hall, home of the College of Environmental Design. Early in May, students there began to create and freely distribute antiwar posters. The Berkeley poster project may have been inspired in part by the posters produced by art students in Paris in May 1968—who were in turn, perhaps, indirectly inspired by the Berkeley protests of the early 1960s. The Paris students had created what they called the Atelier Populaire, producing a series of freely distributed posters. The Atelier Populaire was the name given to themselves by a group of Parisian students at the École des Beaux-Arts. On May 8, 1968, the École des Beaux-Arts went on strike. A series of massive demonstrations was called, involving both workers and students, in Paris and around the country. According to an account by striking students, on May 14 a “provisional strike committee informs the Administrative Council of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts that the students are taking possession of the premises.”25 This passage first appears, in French, in a small book published in Paris in 1969. In Posters from the Revolution, Paris, May, 1968, a translated version appeared that included, in large format, color prints of some of the posters. Records of the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, indicate that the library owns two copies of the 1969 English version, and that one of them is in the library of the College of Environmental Design, where the Berkeley posters were produced. If the book was there in 1970 (and there is every reason to suppose that it was), then it would have been available as a resource for Berkeley faculty and students involved in the Berkeley poster project.

Other lines of apparent or potential connection link the Berkeley posters with the Paris of May 1968. A famous Paris poster from that month shows Adolf Hitler holding a mask of Charles de Gaulle (see fig. 4).26 A corresponding Berkeley poster of May 1970 shows Hitler holding a mask of Richard Nixon (plate 16). Since the de Gaulle–Hitler poster does not appear in the 1968 Paris book Atelier Populaire or in Posters from the Revolution, there must have been several routes of influence between Berkeley and Paris. The behind-the-mask iconology has a long history. In the collection of the Imperial War Museum in the United Kingdom is a German World War I poster, “Hinter der Maske,” showing a lean, angry, red-faced man holding up a smiling, round-faced, white mask—a spy pretending to be a friendly burgher.27 The theme has a still longer history in the wolf-in-sheep’s-clothing fable, which appears in the New Testament (“Beware of false prophets, which come to you in sheep’s clothing, but inwardly they are ravening wolves” [Matthew 7:15]), and in a tale that became associated with an Aesop fable about a wolf, raised among sheep dogs, that reverted to type.

FIGURE 4 [Hitler tenant à la main le masque de de Gaulle (Hitler holding in his hand the mask of de Gaulle)]. Atelier Populaire, May 1968. Bibliothèque nationale de France.

The Paris protests arose most immediately from brutal police attacks on demonstrating students, creating a widespread student movement that was joined by factory workers and other labor groups. A key theme in Paris, as in the Berkeley demonstrations of 1970, was to protest the suppression of free speech, as in the poster “Sois jeune et tais toi” (see fig. 5), in which a silhouette of de Gaulle holds his hand over the mouth of a student and admonishes him, “Be young and shut up.”

FIGURE 5 “Sois jeune et tais toi” (Be young and shut up). Atelier Populaire, May 1968. Bibliothèque nationale de France.

The Paris posters celebrated the solidarity of the students and striking factory workers, mocked state-owned national television as a propaganda apparatus, depicted de Gaulle as a monarch, and scorned an emergency election as a mere plebiscite, after which de Gaulle would simply resume his rule.28 Several posters asserted that the struggle would continue—a slogan that still echoes in European political graffiti decades later. The Vietnam War had less salience in Paris than in the United States in 1968, but it was a theme of some posters and, according to participants, partly motivated their objection to state authority.

French thought and French student politics probably had some influence on developments in the United States, but this influence was mostly indirect and cultural. The works of existentialists Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus had been widely read in American colleges for years. Student and counterculture magazines carried news of the New Left and its thought. French cultural theory that had informed Paris ’68—for example, the Situationist International theories of Guy Debord—was in circulation in the United States from the mid-1960s, although it was not widely known.29 Debord’s La société du spectacle was published in Paris in 1967; the first English translation appeared in 1970. Debord argued that all contemporary experience occurs as spectacle, in which the dominant order presents itself everywhere—public and private, work and leisure—as normal: “The spectacle is the existing order’s uninterrupted discourse about itself, its laudatory monologue. It is the self-portrait of power in the epoch of its totalitarian management of the conditions of existence.”30 American radicals were also familiar with British radical thought. The New Left Review had begun publication in 1960, in London, circulating New Left thinking internationally.

In the United States, the New Left was perhaps most clearly identified with Students for a Democratic Society, although liberal, radical, and countercultural thought was fragmented and widespread in and beyond SDS. Berkeley, a center of political action through the decade, was not reducible to SDS, according to contemporary and later accounts. The SDS itself went through rapid change throughout the period. In addition to the diverse political atmosphere in and accessible to Berkeley, the musical and cultural revolutions of the 1960s were everywhere visible and audible, with the nearby, iconic Haight-Ashbury counterculture and the strong Bay Area presence of rock concerts and psychedelic art. And yet with all the sources that the Berkeley graphic artists had available to them, the overriding tone in May 1970 seems to appeal to fundamentally liberal and democratic values—though of course this might be because as a rhetorical matter the discourse was addressed and not simply expressed. By May 1970, Students for a Democratic Society had become radicalized to the threshold of self-destruction, although SDS leaders were still active at Berkeley. In fact, Tom Hayden, who had helped found SDS and who was the author of its founding manifesto, The Port Huron Statement, addressed an audience at the outdoor theater on campus in May 1970.31

The Paris posters, and the entire Paris ’68 movement, were on the whole much more militant than the Berkeley posters.32 The Paris posters denounced President de Gaulle and the French police, whose brutal suppression of peaceful demonstrations at the Sorbonne and among workers led to waves of protest and the near destruction of the government itself (see fig. 6). At one point, in the face of continued demonstrations and a general strike in all segments of the economy, and fearing that his government could collapse within forty-eight hours, de Gaulle secretly left Paris to consult with a French general stationed in Germany to bargain for army support. The student posters in Paris celebrated a unity and common interest between workers and students in a way that never applied in the United States, where the Nixon administration retained the support of a large segment of the white working class. But for all its militancy, the poster campaign of the Atelier Populaire was deliberately not sectarian. In 2012, William Bostwick interviewed Philippe Vermés, one of the Atelier Populaire artists, on the occasion of the publication of a new book on the Paris posters. Vermés recalls that “when we were occupying the Beaux-Arts, we’d have a meeting every night at 7 P.M. to decide on a slogan. We said, We have to not be Trotskyites, Situationists, anarchists. We have to get the right slogan that hits people the strongest. We’d vote. . . . One time, we made a flag, blue, white, and red. And the red overlapped the other colors, and—no, no, no, we said. Because maybe it’s a Communist red. Everyone had to put their ideologies behind them.”33

FIGURE 6 “La beauté est dans la rue” (Beauty is in the street). Atelier Populaire. Bibliothèque nationale de France.

The Paris posters were almost certainly known to at least some of the Berkeley artists. The first published versions, together with an account of how they were created, in Atelier Populaire: Présenté par lui-meme (Paris, 1968) were succeeded the next year by a large-format English translation copublished by Dobson Books in London and Bobbs-Merrill in Indianapolis as Posters from the Revolution, Paris, May, 1968: Texts and Posters (1969). On the copyright page of both books, here using the English version of 1969, is this statement:

To the reader:

The posters reproduced by the Atelier Populaire are weapons in the service of the struggle and are an inseparable part of it.

Their rightful place is in the centres of conflict, that is to say in the streets and on the walls of the factories. To use them for decorative purposes, to display them in bourgeois places of culture or to consider them as objects of aesthetic interest is to impair both their function and their effect. This is why the Atelier Populaire has always refused to put them on sale.

Even to keep them as historical evidence of a certain stage of the struggle is a betrayal, for the struggle itself is of such primary importance that the position of an “outside” observer is a fiction which inevitably plays into the hands of the ruling class.

That is why this book should not be taken as the final outcome of an experience, but as an inducement for finding, through contact with the masses, new levels of action both on the cultural and the political plane.34

The Atelier Populaire posters may themselves have been inspired by posters from Berkeley in the mid-1960s, when artists were experimenting with silk screen and photo-offset techniques for creating psychedelic poster art and political protest posters. John Barnicoat, author of a standard history of the poster, in an article in Grove Art Online, traces Berkeley psychedelic posters of 1965 back to the late nineteenth century. Rather than suggesting that the earlier Berkeley posters directly influenced the Atelier Populaire posters of 1968, Barnicoat appears to argue that similar political and material circumstances were the occasion of a parallel movement.

The events of May 1968 in Paris also produced posters that were evidence of a new generation asserting itself. A more serious political aim provided the background to the crude, screen-printed images generated by the Atelier Populaire, established in May 1968. Here cooperation between amateur and professional talent resulted in a series of small posters such as the caricature of General de Gaulle in La Chienlit—c’est lui (1968; Paris, Lesley Hamilton priv. col.), which restored the poster to its original function as a fly-posted handbill. Such had been the poster’s development as a sophisticated vehicle, expensive to produce and dependent on the support of the social and business establishments and their technical resources, that when such support was removed, poster design reverted to its origin as a hand-printed sheet. Inevitably, the situation affected both image and form, and helped restore the poster to its original function as a “noisy” street announcement.35

Historian Michael Seidman notes that the Paris posters were “the most striking and enduring cultural legacy” of May 1968.36 He argues that the practical effects of May 1968 in Paris were limited, but that they have achieved a place in collective memory, perhaps in large part because of the afterlife of the posters, and have “become a symbol of a youthful, renewed, and freer France.”37 Marc Rohan, who as a student participated in the Paris demonstrations, recalls that the posters and graffiti “covered the walls” and that they “were to become the most imaginative art form of the period.”38

In an oral history interview, artist Rupert Garcia testifies to a direct link between the Atelier Populaire and posters in the Bay Area. Garcia, then an art student at San Francisco State, recalls that in late 1968 or early 1969,

well, in the art department we did eventually respond, in terms of faculty. . . . We had a big meeting of art students and faculty about how to address the campus strike. And one faculty—I guess, a faculty from England, who had just come back from visiting France and Paris—mentioned to us what he saw some students doing there—which was to make posters. And so we—some faculty and students—organized a poster brigade. And we used Dennis Beall’s print studios and his instruction on how to do silk screen and so we learned this technique, like on-the-job training. There was no course, no class. And I was a liaison between the art department and the other members of the Third World Liberation Front organizations. I would go talk to them and come back, and this kind of thing. And so we began to make posters dealing with the issues—issues from racism to better education to police brutality, anti-war, and much more. I mean, all the issues that were being addressed at that time made for a heady experience. Many of those issues were being dealt with in our poster brigade. And the posters were used in the demonstrations on campus, and some were used outside of campus, and some were sold to raise money to get people out on bail, people who had been arrested. And it was going very well. We had really wonderful teamwork.39

Peace Is Patriotic

In Berkeley itself, the posters from 1970 were clearly a continuation of the local posters from the mid-1960s and earlier.40 In January 1966, Bill Graham began organizing rock music dance concerts at the Fillmore Auditorium in San Francisco, and he hired artists to create posters advertising the events. The posters spread throughout the Bay Area and attracted international attention. The posters, by a variety of artists, suggested both the psychedelic subculture centered in San Francisco and the rock music that was their direct subject. Walter Medeiros, a historian of the posters, describes them as handmade and hand-lettered, with rich decorative patterns, “abstract, undulating, stretched or warped,” with bright colors in unusual combinations, and with images that are “sensual, bizarre or beautiful, philosophical or metaphysical.”41 The handmade posters were then commercially printed in large numbers and distributed throughout the Bay Area, a congenial place for the circulation and viewing of posters. Graham later recalled,

I was possessed. I’d go out there all speeded up on my scooter with my Army pack. . . . I would stick a big pile of posters in there with my industrial stapler. And in my coat, my fiberglass 3M tape, so I could put posters up on steel or concrete, not just wood. I would leave the city at four in the morning and go up to Berkeley . . . [and] when people woke up in the morning, full. Every wall. I knew then that the posters were hitting home, because as I went back down the block, I would see people taking them off the wall for their own.42

The dance concert posters and the Berkeley peace posters also shared a common space that was, it turned out, suited to the display of posters and directed to a public familiar with street poster art. In a 1974 article, Marc Treib described how the mild weather in Berkeley drew people onto the streets, especially in the Telegraph Avenue area just south of campus at Sproul Plaza. After earlier demonstrators had broken storefront windows along Telegraph, owners replaced glass with plywood or with windowless walls, and these surfaces became prime locations for posters, especially “cheap photocopy and offset lithography . . . in near standard format. The machines limit the message size to 8” by 11” or 8½” by 14”, usually one color.” The posters were stapled or taped to telephone poles, walls, and kiosks, becoming a “town crier, the information source.”43 Alton Kelley, one of the dance concert poster artists, observed later that Berkeley and San Francisco were ideal physical settings for the concert posters, a setting that was much the same in May 1970 when the Berkeley peace posters were in circulation. Kelley recalls, “The posters wouldn’t have worked in any other city. New York’s too big, and nobody walks in L.A. So what you had in San Francisco was the right combination of people walking around the streets and timing. Everything that was happening in the culture came together—at least for a while.”44

The dance concert posters were not “political” in the same way that the peace posters were. In his dissertation on the psychedelic rock concert posters, Kevin Moist nevertheless identifies what he calls a “form of subcultural visionary rhetoric.” Moist writes that in Haight-Ashbury, the core of the psychedelic culture, “during the mid-to-late 1960s we find nary a protest nor political demonstration of any kind.”45 Moist argues that the Haight subculture did have a politics, but that hippie politics refused what it and Moist characterized as the old-fashioned, polarized, either-or of the New Left taking on the Establishment. Moist elaborates on the cultural meanings and the politics of “dropping out” as a rejection of the futility and violence of the old order. To be sure, the New Left had its share of ambitious posturing and sectarian struggle, although Moist’s portrayal of these traits is too sweeping. In any case, Moist’s observation about the dropout culture as an alternative prompts the question of whether the Berkeley peace posters themselves share the doctrinaire rigidity Moist seems to attribute to the New Left. The psychedelic posters were available to the artists and viewers of the Berkeley peace posters as examples of the power of poster art. It may even be that, besides enriching the storehouse of poster styles, the dropout culture’s suspicion of sectarian leftism tempered and provided a more complex context for the peace demonstrations of May 1970.

Matthieu Poirer argues that the Paris uprisings of May 1968 were directly linked to the international and the specifically French psychedelic avant-garde of the 1960s. Poirer draws attention to the immersive, participatory sensory disruptions of French psychedelic art that stood in contrast to the countercultural utopian dropout strain noted by Moist. May 1968, argues Poirer, drew inspiration from the ambition of psychedelic art to change “consciousness, disturbing sensorial stability.” It also drew inspiration from the development of the “happening,” an immersive artistic and theatrical experience that directly engaged the audience. Poirer observes that “it is no coincidence that the [French] minister of education at the time, Edgar Faure, likened May 1968 to a large ‘happening.’” In French psychedelic visual art, Poirer continues, “these intransitive works appeal directly to the senses and are subsequently stripped of any cross-reference to external style other than their own phenomenological reality.”46 In the case of the Atelier Populaire, it seems evident in retrospect that the ambition of the poster artists to induce something like the direct, pure, social, and perceptual disruption of the happening and of psychedelic art was paired simultaneously with traditional poster-art appeals to militant political dissent. Such a pairing may have contributed to their peculiar power and to the unlikelihood that they would stimulate lasting social and political change. Writing of the British psychedelic scene in the 1960s, Andrew Wilson argues that “1968 marked the moment in which a belief that social and political change might happen naturally was exchanged for an understanding that such change had to be organized for, willed and made to happen. . . . However necessary thought, feeling, and imagination might be for such a revolution to succeed, the events of May 1968 exposed the split between those voyagers of inner space who believed that imagination was enough, and activists who understood that social and political struggle entailed a return to more orthodox—even Marxian—forms of analysis, conflict and action.”47

Walter Medeiros, in contrast to Moist on the San Francisco scene and Wilson on the British 1960s, describes not so much a sharp break between the political and the psychedelic but a highly complex mix of shifting activities and people, many of whom crossed the lines of art, music, and politics. It seems likely that attendees at dance concerts and political rallies, though sometimes entirely separate populations, were often the same people. Rather than viewing the political and the cultural as two separate strains, and without simply collapsing the whole Bay Area experience of the 1960s into an amorphous mix, Medeiros sees common strains of impatience with politics and culture stimulating a variety of sometimes divergent, sometimes interactive political and cultural events.48 Underground newspapers in the Bay Area liberally mixed sex, drugs, rock and roll, radical cultural movements, massage parlors, Black Panthers, and antiwar activism. A cover drawing in the Berkeley Barb for June 12–18, 1970, is typical: a pistol-packing seminude woman; a naked cop with Black Panther tattoo carrying a “Now” placard with raised black and white fists; a Capitol dome toppling in an explosion of smoke and psychedelic stars; a street fighter raising his fist; and the slogan “Only a United People’s Liberation Front Can Win—The Pigs Are Everywhere.”

It seems clear that there were at least some direct connections among the Berkeley peace posters of May 1970 and the poster art of the Atelier Populaire, the politics of Paris in May 1968, and the worldwide uprisings in 1968. But it seems unlikely that May 1968 was a dominating force in the rhetorical consciousness of the United States in the late 1960s or in May 1970. The war in Vietnam and turmoil over civil rights and racial justice, together with assassinations, riots, and political instability, consumed the country’s attention. The assassination of John Kennedy in 1963 created grief and uncertainty. Historian James T. Patterson identifies 1965, “the year of military escalation, of Watts, of the splintering of the civil rights movement, and of mounting cultural and political change and polarization, . . . as the time when America’s social cohesion began to unravel and when the turbulent phenomenon that would be called ‘the Sixties’ broke into view” and “lasted into the early 1970s.”49 Every year seemed to bring new disturbances, with even the great progressive changes in civil rights—voting rights, public accommodations—bringing their own backlashes. In 1967, riots spread through the inner city of Detroit. That fall saw large demonstrations in Washington against the war. In addition to the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy, 1968 brought the Tet Offensive and Lyndon Johnson’s announcement that he would not run for reelection.50 George Wallace of Alabama emerged as a candidate of the Southern backlash against civil rights, and Richard Nixon won the presidency with a promise to execute his secret plan to end the war and to restore order in the streets, along with the code words of the new Republican Southern strategy. The year 1969 brought further frustration in Vietnam and further division at home. The political and civil turmoil of the 1960s was matched by a widespread cultural upheaval. The Berkeley posters themselves have direct antecedents in Paris of May 1968, but the larger political and rhetorical climate of Berkeley in May 1970 was distinctively American.

The antecedents of the Berkeley peace posters reach beyond the recent Paris posters and the local psychedelic posters to the nineteenth-century development of the poster for commerce, art, propaganda, and protest, and further back through a long history of prints, handbills, broadsides, signs, and graffiti.51 In the United States, poster art was employed as government rhetoric in World Wars I and II, as well as in the New Deal. The New Deal stimulated a rich government investment in public arts of all sorts, partly to develop a sense of national cohesion and optimism, and partly as a means of providing direct support to artists in all spheres—painters, writers, actors, musicians, photographers, filmmakers, designers, architects, and poster and print artists. Roger G. Kennedy and David Larkin note that in announcing the New Deal, Franklin Delano Roosevelt “was not announcing a program of princely patronage or largesse. He was, instead, inviting each of his countrymen, artists among them, to come forward in a covenant of service. Artists were among the many who needed work in 1932, and the nation needed the work artists could do.”52 Kennedy and Larkin emphasize that New Deal art was not simply propaganda or make-work, but a diverse and needed contribution to the public good “that summoned forth pride out of common experience.”53 In his pioneering 1987 study of the posters produced by artists recruited by the Works Progress Administration, Christopher DeNoon recalls the ephemerality of the posters. From 1935 to 1943, WPA artists “printed two million posters from thirty-five thousand designs.” Of all those posters, only about two thousand are known to have survived. With the coming of World War II and after a red-baiting witch hunt against WPA art programs led by Martin Dies—a headline-hunting, conservative, anti–New Deal congressman from Texas and chair of the House Un-American Activities Committee—the WPA project came to an end, and most of the posters disappeared into landfills and pulp mills, along with much other New Deal public art.54 The Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs Division collected 907 of the WPA posters in the 1940s; that collection is now supplemented by the WPA Living Archive project, which collected additional posters from various sources. By 2012 the Living Archive had brought the total of rescued posters to 1,601.55

The WPA posters were created for the most part by the silk screen process. Anthony Velonis, a WPA poster artist who taught classes in the technique to students and fellow WPA artists, wrote a classic forty-four-page handbook on the method. Velonis remarked that silk screen printing, although two thousand years old, had not been used in the United States until the early twentieth century, and yet, despite the availability of various mass production printing techniques, the “Chinese stencil process has had a greater proportional growth the last five years [before 1939] than any other modern printing technique.” Velonis observes that “although silk screen cannot approach the chiaroscuro of offset and lithography, it makes up for this by the richness of its pigment layer and the highly valued effect of its ‘personal touch.’” And, he adds, “its initial cost is much less.”56 The WPA posters promoted public health and safety, tourism and travel, exhibitions and performances, and a wide variety of community themes (see figs. 7 and 8).

FIGURE 7 “See America. Welcome to Montana.” Jerome Rothstein, Works Progress Administration. United States Travel Bureau. WPA Poster Collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

FIGURE 8 “Work Pays America! Prosperity.” Vera Bock, Works Progress Administration, 1936–41. WPA Poster Collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

President Roosevelt spoke repeatedly about the pragmatic need to put aside class and regional conflict. FDR sounded a similar note when he encouraged tourism and travel as an economic stimulus and as a way to encourage citizens to cultivate their shared identity as Americans. The WPA poster “Work Pays America!,” by Vera Bock, echoes a theme common in Roosevelt’s speeches—that in the Great Depression, recovery depended on stimulating both the farmer and the laborer; each needed to be put back to work to aid the recovery of the other. While campaigning for a second term in 1936, FDR’s campaign train made a short stop in Hayfield, Minnesota, where he began his rear-platform remarks by referring to tourism and regional and economic mutuality:

I am glad to come to this section of Minnesota. I have never been on this railroad before. I hope in the next three or four years to come through by automobile and get a better idea of this country.

One of the things we ought to think a lot about in this campaign is what has happened to our national point of view in the last four years. In every section of the United States we have gained the understanding that prosperity in one section of the country is absolutely tied in with prosperity in all the other sections. Even back in the Eastern States and cities, they are beginning to realize that the purchasing power of the farmers of the Northwest will have a big effect on the prosperity of the industry and of the industrial workers of the East. In just the same way, I know you realize that if the factories in the big industrial cities are running full speed, people will have more money to buy the foodstuffs you raise.57

By the late 1930s, the Federal Arts Project began to shrink, owing to changing policies and an economy stimulated by defense preparations. DeNoon writes, “In 1942, after the United States entered World War II and the nation’s energies turned in a new direction, the Federal Art Project was transferred to Defense Department sponsorship and renamed the Graphics Section of the War Service Division. Under this new sponsorship, the government-employed poster artists produced training aids, airport plans, rifle sight charts, silhouettes of German and Japanese aircraft, ‘Buy Bonds’ booths, and patriotic posters such as one designed to encourage homefront knitting: ‘Remember Pearl Harbor—Purl Harder.’”58 The themes and motifs in the World War II posters (see figs. 9–13) are all echoed, sometimes with new meanings and valences, in the Berkeley antiwar posters of May 1970—speech and silence, the safety of children, unity across class and racial boundaries, the flag.

FIGURE 9 “Silence Means Security.” Office for Emergency Management. Office of War Information. Collection of the author.

FIGURE 10 “Who Wants to Know? Silence Means Security.” US Adjutant General’s Office, 1943. World War II Poster Collection, Digitized Collections, Northwestern University Library.

FIGURE 11 “Don’t Let That Shadow Touch Them. Buy War Bonds.” Lawrence Beall Smith, US Department of the Treasury, 1942. World War II Poster Collection, Digitized Collections, Northwestern University Library.

FIGURE 12 “Men Working Together!” Office for Emergency Management, Division of Information, 1941. World War II Poster Collection, Digitized Collections, Northwestern University Library.

FIGURE 13 “Give It Your Best!” Office of War Information, 1942. World War II Poster Collection, Digitized Collections, Northwestern University Library.

The WPA artists and their successors who created the World War II posters reinvented a genre that had first flourished in the United States, Europe, and other participating nations in World War I. Pearl James writes of the World War I posters that “mass-produced, full-color, large-format war posters . . . were both signs and instruments of two modern innovations in warfare—the military deployment of modern technology and the development of the home front. . . . Posters nationalized, mobilized, and modernized civilian populations.”59 A strikingly similar claim is offered by William L. Bird Jr. and Harry R. Rubenstein in the opening pages of Design for Victory, their account of home-front posters in World War II America: “World War II posters helped mobilize a nation. Inexpensive, accessible, and ever-present, the poster was an ideal agent for making war aims the personal mission of every citizen.”60

The widespread view that World War II was a total war, in which victory depended on the mobilization of national industries, had the effect of at least implicitly justifying large-scale bombing campaigns against industrial and civilian targets. If every citizen was a soldier, every citizen was a potentially legitimate target. The home-front posters themselves sometimes emphasized the risks of defeat, but were largely directed at the mobilization of effort and related themes of the “loose-lips-sink-ships” variety, war bond campaigns, and thrift. Private manufacturers joined the government in the production of home-front posters. “The volume of privately printed posters for factories and plant communities was said to be greater than the number of posters issued from any and all sources during World War I,” Bird and Rubenstein write.61 When large advertising firms brought their talents to the poster effort, debates took shape in the Office of War Information, which was to “review and approve the design and distribution of government posters. Eventually, contending groups within the OWI clashed over poster design. While some embraced the poster as a demonstration of the practical utility of art, others valued it as evidence of the power of advertising. . . . [Those] who saw posters as ‘war graphics’ favored stylized images and symbolism, while recruits drawn from the world of advertising predictably wanted posters to be more like ads.”62 The advertising industry won the argument, partly by winning the support of conservative members of Congress. This in turn influenced the development of home-front posters and secured a financial windfall for advertising firms. During World War II, the effect of posters was almost certainly exceeded by radio, motion pictures, and print. After the war, the introduction of television contributed to the decline of the poster as a primary mode of public and commercial communication. “Not since World War II have government, business, and labor used a wide array of posters as a major form of communication,” Bird and Rubenstein conclude.63 Although their importance as a medium of mass communication diminished after World War II, posters did appear regularly through the 1960s, both as wall posters and as portable signs in citizen demonstrations for peace and civil rights (see figs. 14–17).

FIGURE 14 “Sit-In and Demonstration (Atlanta, Georgia): Congress of Racial Equality, 1963.” The sign carried by the man being assaulted by police officers reads, “July 4th 1776 to 1863: Slavery. 1863–1963: Poverty. Freedom Now. L. I. CORE.” Robert Joyce Papers, 1952–1973, Historical Collections and Labor Archives, Special Collections Library, University Libraries, The Pennsylvania State University. Box 6, Folder 9.

FIGURE 15 “March for Peace (Washington, D.C.): Stop the Bombing; End the War, 1965.” Robert Joyce Papers, 1952–1973, Historical Collections and Labor Archives, Special Collections Library, University Libraries, The Pennsylvania State University. Box 6, Folder 12.

FIGURE 16 “Reaffirm America’s Revolutionary Heritage; Florida Confronts the Pentagon; Vets for Peace in Vietnam: March on Washington Against the War in Vietnam, October 21–22, 1967.” Thomas W. Benson Political Protest Collection, Historical Collections and Labor Archives, Eberly Family Special Collections Library, University Libraries, The Pennsylvania State University. Photograph by the author.

FIGURE 17 “Save Lives, Not Face.” March on Washington against the war in Vietnam, October 21–22, 1967. Photograph by the author.

The psychedelic posters, especially in the Bay Area, helped stimulate a poster culture in the 1960s, which was amplified by the establishment of commercial poster production for private use. College dormitory walls were commonly decorated with locally purchased, mass-produced posters that were in national circulation. Also in the 1960s, some fine artists, turning away from the dominant abstract and pop styles, were creating visual art with strong social content.64 No later than 1965, antiwar posters and paintings were in wide circulation. For the catalogue of an exhibition of protest posters at the New School in New York, in October–December 1971, David Kunzle wrote, “The Poster of Protest was triggered by the sudden, unexpected and massive escalation of the war in Vietnam 1965–66. By 1968 enough antiwar posters had appeared to form an exhibition (mounted in Italy) containing about seventy items. Two years later this number had more than doubled, but there are signs that the wave of the ‘commercial’ poster of protest, with which we are concerned here, is beginning to break, or to move in a new direction: the non-commercial, utilitarian ‘action’ poster, modeled on the famous French student affiches de mai.”65

At Berkeley in May 1970, posters were simply laid out in stacks on tables in the lobby of the College of Environmental Design. Every day, it seemed, there was a fresh supply.66 Lincoln Cushing says that at Berkeley the “short-lived workshop . . . created an estimated fifty thousand copies of hundreds of works.”67 The posters were made with the approval and assistance of the University Art Museum and the faculty of the College of Environmental Design. According to Cushing, “UC Berkeley art history professor Herschel B. Chipp was a faculty advocate for the workshop artists, and he threw his support behind a student-curated exhibition at the then-new University Art Museum. It included work from the University of California, the California College of Arts and Crafts, the San Francisco Art Institute, Stanford, and other schools, as well as posters from Mexico and Paris from May 1968.”68

In his Art of Engagement: Visual Politics in California and Beyond, Peter Selz, former director of the University Art Museum, recalls,

Many antiwar posters were produced in the University Art Museum on the Berkeley campus during this time. In response to the American invasion of Cambodia in 1970, there was an outcry against the war among students, faculty, and staff at Berkeley, as at many universities in America. As director of the University Art Museum at the time, I was approached by students who wanted to turn the gallery into “campus central” for the printing of posters and the mimeographing (since this was before the time of the photocopier) of position papers. I felt that this action was called for, even though the gallery was just then the venue for two major sculpture exhibitions. . . . I placed the sculptures behind a screen to make room for silkscreen presses and mimeograph machines, feeling that, just as art is often political, politics is sometimes art.69

At the time, of course, these posters were not presented in any particular groupings, though perhaps the recurrence of themes would have helped some of them become recognizable while framing the others. The posters are primarily antiwar, at least by context if not by direct reference; a few refer to civil rights or the larger political process. In any case, the political themes raised in the posters do not divide neatly into mutually exclusive categories; instead, they overlap and intertwine along a variety of dimensions. Our groupings here should thus be regarded with some reservations, to avoid political or rhetorical reductionism. In any case, though the “arguments” of the posters are crucial to their meanings, the posters are not, taken one at a time or together, reducible to any single proposition.

Most of the posters are original art on silk screen; some are based on photographs, and some are produced by photo offset. Some of the art is purely typographic. The color palette is typically limited, giving the posters a simplicity, directness, immediacy, vividness, and in some cases a beauty that is striking. All of it provides symbolic dimensions through pure design by creating tone and stance.

One cluster shows a variety of Vietnamese or more broadly Asian themes, with strong appeals for identification. In “This Is Life—This Cuts It Short” (see fig. 18), a mother and child (life) are juxtaposed against a rifle (this cuts it short) gripped in an unknown hand. The mother and child are clearly Asian but are also familiar, in a pose that might suggest a Madonna and child. The child directs its gaze at the viewer, with a look that, in context, must suggest alarm, even fear. The theme of violence directed against women and children recalls the My Lai massacre of the previous year, and of continuing stories of civilian deaths in Vietnam, which was the subject of the widely circulated “And Babies? And Babies” poster created in December 1969 by members of the Art Workers Coalition. “And Babies” reproduces a photograph of the My Lai massacre showing a row of bodies, including several babies; printed on the poster is the question “And babies?” and the answer, “And babies,” from an interview of Paul Meadlo, one of the US soldiers involved at My Lai, conducted by Mike Wallace of CBS News. The “And Babies” poster had been commissioned by the Museum of Modern Art and the Artist Workers Coalition; when a proof copy of the poster was shown to William Paley and Nelson Rockefeller, trustees of MoMA, the poster was rejected and the MoMA director was fired. The Artist Workers Coalition printed the posters on its own, and they were quickly circulated in New York and around the world. Copies of the poster apparently arrived in Berkeley in late December 1969 or early January 1970.70

FIGURE 18 “This Is Life—This Cuts It Short.” Thomas W. Benson Political Protest Collection, Historical Collections and Labor Archives, Eberly Family Special Collections Library, University Libraries, The Pennsylvania State University.

“Does He Destroy Your Way of Life?” (fig. 19) repeats the appeal to identification, but adds a theme of distance. A peasant farmer, shown in silhouette, follows a buffalo pulling a plow. The viewer may identify with this homely, harmless figure as a fellow creature, but, with the buffalo and the conical straw hat, the poster also denotes something exotic and remote, amplifying the question “Does he destroy your way of life?”—a question clearly addressed to an American viewer who has been told by his government that the Vietnam War is required to halt worldwide Communist aggression. On the contrary, the poster seems to assert, this is a figure whose simplicity should prompt us to identify with his humanity, but whose remoteness should convince us that he is not a threat to us, on the other side of the world.

FIGURE 19 “Does He Destroy Your Way of Life?” Thomas W. Benson Political Protest Collection, Historical Collections and Labor Archives, Eberly Family Special Collections Library, University Libraries, The Pennsylvania State University.

The danger to the Vietnamese implied by figures 18 and 19 is more directly asserted in plate 4, “Vietnamization,” which shows a photograph of a bloodied mother and infant, apparently collateral damage from a US attack. These depictions of victims of war’s violence are a counterpart to a common theme of war posters, in which images of victims or potential victims are offered as justification for war (compare plate 4 to fig. 11, “Don’t Let That Shadow Touch Them”). The “Vietnamization” poster also uses the trope of irony by juxtaposing a verbal quotation with the actuality that it implies—a trope also at work in “And Babies.” Such comparisons appear frequently in the posters, sometimes by using contrasts within the imagery, sometimes in contrasts between the image and the words. Juxtaposition is a key rhetorical structure in generating meaning. Ironic juxtaposition motivates plate 5, “It Became Necessary to Destroy the Town to Save It”—the title draws on a quotation from an on-camera interview between a US Army major and AP reporter Peter Arnett. The poster features a photograph by Paul Avery of a terrified, elderly Vietnamese couple.71

Other posters showing Vietnamese or Southeast Asian settings are “Nature Is Beautiful (So Is Human Nature) Conserve It” (plate 2), one of several posters gesturing toward the developing environmental movement, and in this case suggesting a link between the environmental movement and the peace movement from which it seemed in danger of diverging; and “Free Asia—U.S. Get Out Now” (plate 6); “Asia for Asians!!” (plate 7); “Her Suffering for Our Comfort? STRIKE” (plate 8); “Vietnam: Spilled Blood Split the Country” (plate 30), again an image of a Vietnamese mother, this time with a dead or injured baby—the country split is the United States; and “Unity in Our Love of Man” (plate 33). “Did You Vote for This? Who Did?” (plate 13) is based on a 1968 AP photograph of the bodies of US Marines on Hill 689 in Khe Sanh, South Vietnam.72 The image of a woman carrying a child in plate 30 is apparently based on a news photograph of a Vietnamese woman carrying a horribly burned baby “after an accidental napalm raid twenty-six miles southwest of Saigon.”73

“Did You Vote for This? Who Did?” is an indirect invocation of the political order in the United States, and, for those who remember, a reminder that both Lyndon Johnson (in 1964) and Richard Nixon (in 1968) won the presidency with promises of peace—which were then contradicted by their actions—and that the evident futility of the war drove Lyndon Johnson from the presidency in 1968. The “Who Did?” is a rhetorical question, implying that because both winning candidates—and in 1968 both Hubert Humphrey and Richard Nixon—promised peace, in effect no one voted for “this.” Similarly, “Vietnam: Spilled Blood Split the Country” refers to the double collateral damage of the war—to innocent civilians in Vietnam and to the civic peace of the United States. Implicitly, such appeals are not a rejection of the political order in the United States but a lament for its weakening by the war. plate 26, “War Is Unhealthy for America,” similarly implies that the war is damaging the people and America itself, including its civic life.74