Читать книгу Called to Community - Thomas Merton - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

Charles E. Moore

how would you go about destroying community, isolating people from one another and from a life shared with others? Over thirty years ago Howard Snyder asked this question and offered the following strategies: fragment family life, move people away from the neighborhoods where they grew up, set people farther apart by giving them bigger houses and yards, and separate the places people work from where they live.1 In other words, “partition off people’s lives into as many worlds as possible.” To facilitate the process, get everyone their own car. Replace meaningful communication with television. And finally, cut down on family size and fill people’s homes with things instead. The result? A post-familial, disconnected culture where self is king, relationships are thin, and individuals fend for themselves.

On the whole, this destruction of community has only been compounded by the advance of digital technology. As Sherry Turkle observes in her book Alone Together, the web’s promise of “bottomless abundance” has left millions inwardly and relationally famished. We live, Turkle suggests, in a “culture of simulation,” where real, tactile, face-to-face relationships of loyalty and intimacy are all but a memory. Ours is truly an age of isolation, with relationships that may be friction free but also very shallow and fleeting.2

In a culture of connectivity, where we have countless people to text and tweet, millions are under the illusion that a networked life is a rich, meaningful life. But community is more than connectivity. Although it is easier than ever to communicate and stay in touch with one another, we are fast losing the ability to commune with one another. We know how to text, but we don’t know how to converse. We exchange vast amounts of information, but find it increasingly difficult to confide in one another. We no longer know how, or think we don’t have the time, to give each other our full attention. Though we may not be alone in our virtual worlds, we remain lonely. Our lives lack cohesion: we live in pieces, in fragments, lacking any overall pattern or any steady, identifiable community in which to belong.3

Social commentator Michael Frost suggests that our culture has become like an airport departure lounge, “full of people who don’t belong where they currently find themselves and whose interactions with others are fleeting, perfunctory, and trivial.”4 Nobody belongs there, nobody is truly present, and nobody wants to be there. We’re tourists who graze from one experience to another, nibbling here and sampling there, but with very little commitment to bind us to one another. We exist in an untethered “nowhereness,” under the illusion that we are free. And yet, as Robert Wuthnow observes, “community is sputtering to an undignified halt, leaving many people stranded and alone.”5

The disappearance of community has led to a plethora of human and social problems, which have been exposed and explored in countless books. The question this collection of readings seeks to answer is what we can do about it. Many social commentators have addressed the problem and continue to grapple with it. New structures of belonging have been proposed, many of which hold promise. But as good and viable as these may be, the main thrust behind this book is that the answer lies in the hands of God’s people. We need more than new structures. We need a spirit-filled life that is capable of combatting the corrosive ideologies of our age. Only when the church lives out its original calling, as a contrast community and foretaste of God’s coming reign, is there hope for the world. And there is hope. The Bible assures us that through faith in Jesus and by God’s spirit a new kind of social existence is possible. Christ has defeated the principalities and powers that keep people apart. In him relationships can be healed and transformed. This is what being the church is all about.

Although many people bemoan the fact that society is so fragmented, a small but growing number of people are daring to step away from the status quo and follow the beat of a different drummer. Committed followers of Christ from every corner of society and from all walks of life are responding to Christ’s call to embody an integrated spirituality that encompasses the whole of life and is lived out with others. New intentional communities are emerging that bear witness to Christ’s healing power. A radical renaissance is unfolding among disenchanted Christians who are no longer satisfied with either Sunday religion or social activism. Today’s Christians want to be the church, to follow Christ together and demonstrate in their daily lives the radical, transforming love of God.

Of course, in a world in which family life is undermined and faithfulness and loyalty are old-fashioned concepts, living in community will not be easy. The broader culture rarely reinforces values such as fidelity, the common good, and social solidarity. It’s everyone out for themselves. We’re on our own, whether we like it or not. And yet for growing numbers of Christians this world, with its dominant ideology of expressive individualism, is not the final adjudicator of what is or is not possible, let alone desirable. The world Christ was born into was also splintered and confused; it was violent, factious, morally corrupt, spiritually bankrupt, full of tensions, and teeming with competing interests. Yet, into this world a brand new social order erupted. It caught everybody’s attention, and eventually transformed the entire Roman pagan system.

Throughout the history of the church, movements of renewal have arisen. In each instance, the church’s spiritual and corporate life was revitalized. The question before us today is this: Are we ready and eager for a new work of the Spirit in which everything, including our lifestyles and corporate structures, is turned upside down?

If so, this book can help. It is intended to encourage and strengthen the current movement of the Spirit in which people are consciously pledging themselves to live out their faith with others on a radically new basis. Part I presents a vision of community, supplying a theological and biblical ground on which to be God’s people together. Many people seek out intentional community to ameliorate such problems as loneliness, economic injustice, racial division, and environmental destruction. These are good, and yet we must step back and first grasp what God’s plan is for his people and the way in which we are to build for God’s kingdom. Part II tackles the question of what community means and what it takes to nurture it. Forming community is not just living close to one another. Prisoners do that. Rather, community demands personal sacrifice and personal transformation.

The ideal of togetherness is one thing; becoming a vibrant, united circle of comrades that remain together is another. Part III covers some of the nitty-gritty issues of living in community. New communities of faith often fall to pieces simply because they are not able to navigate the mundane matters of human coexistence. We need to unlearn certain ways of being before we can go the long haul with others. Finally, Part IV addresses the need for every community to see beyond itself. Community is not an end in itself. An inward looking community will eventually implode. Christ gathered his disciples together to serve a purpose larger than themselves, to pioneer God’s coming reign in which all things will be reconciled.

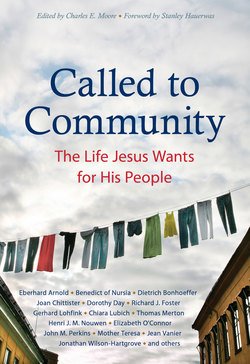

The selections in this volume are, by and large, written by practitioners – people who have lived in community and who have discovered what it takes to fruitfully live a common life with others. The writings of Eberhard Arnold, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, and Jean Vanier are especially notable. Nothing can replace Arnold’s Why We Live in Community, Bonhoeffer’s Life Together, or Vanier’s Community and Growth. These books should be read in their entirety. Yet there are countless other voices that have wisdom and insight to offer. This collection brings many of these diverse voices together to address some of the most essential issues of community life.

You may be reading this book on your own. However, it is best read and discussed together with others. There is little point in reading a book such as this unless it actually helps you to build community with others. Whether you have just begun thinking about communal living, have already embarked on a shared life with others, or have been part of a community for many years, the selections in this collection are meant to encourage, challenge, and strengthen you to follow the call to live as brothers and sisters in Christ. Growing together takes time. That’s why the book has been divided into fifty-two chapters, so you can read one chapter a week and then meet together to discuss what you’ve read.

It has been said that true community is all or nothing, and that communities which try to get there by degrees just get stuck. This may be true. And yet, much like a healthy marriage, it takes time and wisdom to build a community. It also takes very little to break and destroy a community. Perhaps this is one of the reasons why so few people dare to commit themselves to building a common life. As Henri Nouwen writes, fearful distance is awful, but fearful closeness, if not properly navigated, can turn into a nightmare.6

Thomas Merton once noted that living alone does not necessarily isolate people, and that merely living together does not necessarily bring us into communion with one another.7 So what is the key to communing with one another? Hopefully the selections in this book will help to answer this question. In the meantime, community as Christ intended it demands, if nothing else, a commitment to care for one another – to be our brother’s and sister’s keeper. Without simple deeds of love, community is not possible.

Dr. Paul Brand, who devoted himself to eliminating leprosy, was once working alone in an attic when he came across some boxes of skeletons that had been dug up from a monastery. He remembered a lecture he heard given by anthropologist Margaret Mead, who spent much of her life researching prehistoric peoples. She asked her audience, “What is the earliest sign of civilization? A clay pot? Iron? Tools? Agriculture?” No, she claimed, it was a healed leg bone. Brand recalls:

She explained that such healings were never found in the remains of competitive, savage societies. There, clues of violence abounded: temples pierced by arrows, skulls crushed by clubs. But the healed femur showed that someone must have cared for the injured person – hunted on his behalf, brought him food, and served him at personal sacrifice. Savage societies could not afford such pity. I found similar evidence of healing in the bones from the churchyard. I later learned that an order of monks had worked among the victims: their concern came to light five hundred years later in the thin lines of healing where infected bone had cracked apart or eroded and then grown back together.8

Community is all about helping each other – caring enough to invest oneself in the “thin lines of healing.” There is no other way to have community. The apostle Paul wrote, “The only thing that counts is faith expressing itself through love” (Gal. 5:6). Words and ideas, forms and structures can take us only so far. In the end, it’s a matter of whether we will lay down our lives for one another. For Christ’s followers, this is not just a matter of obedience but the distinguishing mark of our witness. Jesus says, “A new command I give you: Love one another. As I have loved you, so you must love one another. By this everyone will know that you are my disciples, if you love one another” (John 13:34–35). ◆

1 Howard A. Snyder, Liberating the Church: The Ecology of Church and Kingdom (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1983), 113–114.

2 Sherry Turkle, Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other (New York: Basic Books, 2011), 6–12.

3 Robert N. Bellah, Habits of the Heart: Individualism and Commitment in American Life (New York: Harper and Row, 1985), 177.

4 Michael Frost, Incarnate: The Body of Christ in an Age of Disengagement (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Books, 2014), 16.

5 Robert Wuthnow, Sharing the Journey: Support Groups and America’s New Quest for Community (New York: Simon and Shuster, 1994), 5.

6 Henri J. M. Nouwen, Lifesigns: Intimacy, Fecundity, and Ecstasy in Christian Perspective (New York: Doubleday, 2013), 19.

7 Thomas Merton, New Seeds of Contemplation (New York: New Directions Books, 1972), 55.

8 Paul Brand and Philip Yancey, Fearfully and Wonderfully Made (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1980), 68.