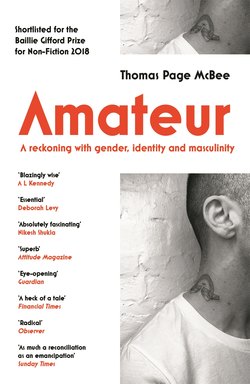

Читать книгу Amateur - Thomas Page McBee - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеWhy Am I Doing This?

Why do men fight? What makes some of us want to get hit in the face? What makes others show up to watch?

What makes a man?

When I first began injecting testosterone, I was thirty years old and needed to become beautiful to myself. I clocked my becoming primarily in aesthetic terms: the T-shirt that now fit me, the graceful curl of a biceps, the glorious sprinkle of a beard. I loved the way men looked, and smelled, and held themselves. I loved their lank and bulk and ease, their straight-razor barbershop shaves, their chest-first centers of balance. I loved the quiet efficiency of the men’s restroom, the ineffable physical joy of running alongside my brother, the shadows we cut against the buildings we passed.

I loved being a man in that I loved having a body. I had surgery to reconstruct my chest; I stuck a long needle into the meat of my thigh each week; I changed my name and my place in the world—all so I could quit hiding behind pulled-low baseball hats and rash guards, free to pull off my shirt and jump right into the waves.

The joys I found at first were daily, simple, and rooted in the warm physicality of a new freedom—toweling off after a shower and catching a glimpse of my flat chest in a foggy mirror; the way clothes suddenly fit my squarer shoulders and slimmer hips. The extra muscle mass that squared my walk, broadened my hands, my calves, my throat. I touched the dip of my abs, half-naked in the bathroom, and the muscle and skin synced in the mirror. I turned, and he turned. I smiled, and he smiled. I expanded, and so did he.

Stories about trans people, when we hear them at all, often end with such shining symbolism, meant to indicate that the man or woman in question has succeeded, in the transition, in the grand task of finally being themselves. Though that’s lovely, and even a little true, in the same way a pregnancy or a near-death experience can act on the body like gravity, reshaping our days and memories and even time around its impact—it isn’t where my story ends. Not even close.

I am a beginner, a man born at thirty, with a body that reveals a reality about being human that is rarely examined. Most of us experience gender conditioning so young—research shows it begins in infancy—that we misunderstand the relationship between nature and nurture, culture and biology, fitting in and being oneself.

This book is an attempt to pull apart those strands. It also became, as I wrote it, a kind of personal insurance, a way to track and shape my own becoming in a culture where so many men are poisonous.

I too come from a long line of poisonous men.

• • •

As the testosterone took hold and reshaped my body, its impact as an object in space grew increasingly bewildering: the expectation that I not be afraid juxtaposed against the fear I inspired in a woman, alone on a dark street; the silencing effect of my voice in a meeting; the unearned presumption of my competence; my power; my potential.

I could feel myself forming in response to conference calls and tollbooth workers and first dates. I was like a plant in the sun, moving toward whatever was rewarded in me: aggression, ambition, fearlessness.

So I shrugged into men’s T-shirts, which suddenly and beautifully fit, trying to pretend that I wasn’t stuck between stations, the static giving way to errant pieces of concerning advice I picked up along the way, a mounting dissonance I pushed aside until an otherwise ordinary spring day when the troubling gap between my past life and my new body could no longer be ignored.

• • •

To the strangers nearby on Orchard Street, the scene must have seemed innocuous. I looked like any other Lower East Side white guy in his thirties: tattooed, skinny, in sneakers and sunglasses. But I was just four years on testosterone. My beard, complete with errant gray hairs, telegraphed a life I hadn’t yet fully lived.

Plus, my guard was down. I’d just left Jess, my new girlfriend, upstairs in my apartment, the promise of an empty evening spread out before us, and I was on my way to the bodega for ice cream when I clocked that the new restaurant with the beautiful front window had finally opened up next door. With a learned confidence I texted, “I’m taking you here tonight,” alongside a photo I snapped of the “modern British” spot, capturing—in the glarey bounce of my accidental flash—its impossibly cool new denizens, framed by that window in a soft and romantic light.

“Hey!” I looked up, catching the gooey spring light through the trees like a breath before going under, knowing, in the way of animals, that I’d surrendered my night to the big-bicepsed guy in a white T-shirt coming my way. “Are you taking a picture of my fucking car, man?” he shouted, his voice strangely hoarse.

I studied his approach, the moment expanding already into something bigger, people dumbly moving out of the way, gawking but not interfering. This was the third near scuffle I’d found myself in, in as many months. It was otherworldly the way an otherwise-idyllic moment could suddenly tip toward violence. As he came into focus, I locked up with dread.

A queasy fear wavered through me.

The Before me wanted to run, as I had run from my stepfather as a child, this stranger and the man who’d raised me sharing, momentarily, the same scary, bald menace.

“Hey!” the stranger said. He had dark, wavy hair and a blurry mass of tattoos on his forearm, and the unkempt look of the newly divorced. He seemed drunk.

I intuited that he wanted attention, that he hoped to not only cause a scene, but to leave the exchange with black-eyed proof of it.

Men don’t run. The unwanted thought appeared in my brain, through the static.

And so I heaved a great sigh and turned toward him because that’s what men do. I asked him in the lowest tone I could rumble “What in the fuck” he wanted. He pointed at a bright red Mercedes parked in front of the restaurant—the kind of car that looked like a dick. Sweat clung to his face, too much for the chilly afternoon. I took in the wildness in his eyes and was surprise to feel both scared of and sorry for him. What would Mom say? Keep it in perspective. The voice was so precisely hers, it was as if she were really next to me. Thomas, she warned me, when I balled my fists.

He looked haunted, I thought, relaxing my hands.

“I was taking a photo of the restaurant in front of your car,” I tried, softening my tone a bit, breaking the rules of the scene. “I want to take my girlfriend on a date there.” I remembered, at the last moment, not to add an upward lilt to the end of my thought.

“I saw the flash!” he growled, beyond logic, a man committed to his part.

That was the worst of it, I realized. He couldn’t even see me.

I could be anyone.

• • •

“Men don’t hug,” my uncle told me, extending his hand on a warm day a few years before. It was offered kindly, my new life a stream of unsolicited advice, a guide to the construction of a passable masculinity.

He wasn’t wrong. Jess was often the only person who touched me. It struck me that this unfriendly, unshaven man before me now needed human contact.

I too knew what it was like to be near-mad with that sort of need. I may have learned through dumb practice to walk with my chest out, just as I’d trained myself to limit exclamation points in my correspondence, but I felt all the absences my male body created too: the cool distance of friends in tough moments, stemming to some degree from the self-conscious way I held myself apart from women especially, so concerned with being perceived as a threat that I’d become a ghost instead. I’d accepted these prices of admission at first, but lately every day felt like a struggle against a bad translation. What had happened to me?

Done with the charade, I turned away from the angry stranger on Orchard Street, but he clotheslined me as I attempted to move on, his meaty arm stretching out across the length of my chest scars, matching with odd precision the reminder of the technology that allowed me this moment, this rich reward of being “in the right body” at last.

I could smell a mint on his breath, and the confirmation of liquor beneath it. It was late afternoon. I looked at him sadly. “Give. Me. Your. Phone,” he said, emphasizing each word, as if he sensed my empathy and wanted to destroy it.

He and I both waited for me to do something. But what? He had seventy-five pounds and five inches on me. Was I to hit him? Could I? I studied the dart of his eyes. I could, if I had to.

A base and primal instinct grabbed me as I waited for him to twitch. It felt terrible and good to give into it. I stared at him, calculating the distance between us. He wobbled, and then smiled viciously when I flinched, telegraphing the kind of masculinity that I knew, that I could smell, compensated for some deep maw of insecurity. It was hard to tell, as it always is, if he was the kid who got bullied or the bully himself. Still, a part of me wanted to live out that worn masculine narrative of risking my body to prove my right to exist in it.

You are a child of the universe, read the poem my mom had given me in a birthday card long ago, you have a right to be here. Grief whistled through my chest. My phone buzzed, disrupting our dark reverie. It was surely Jess, asking after me. I wanted to be upstairs with her, eating ice cream in that narcotic new-love bliss. Why was I down here, making my body a weapon instead?

I was a man, that much was clear. But, years after I became one, I still wondered what, exactly, that meant.

• • •

It wasn’t lost on me that others were asking the same question.

The first few years I’d injected testosterone coincided with a period of anxious headlines about men in economic turmoil. Post-recession, a surge in suicides, drug addiction, and even beards were all blamed on a broader insecurity about the massive loss of jobs and the shake-up of male-led households after the crash. It was dubbed a global “masculinity crisis.” (This idea, not new in academic circles, now caught fire in popular culture.) In the United States, the story went, men were (sometimes reluctantly) becoming stay-at-home dads, or going back to school in traditionally female-dominated fields such as nursing, or—to avoid doing that—moving back in with their parents and playing video games all day. It was, according to a 2010 cover story in The Atlantic, “the end of men.”

A certain sort of man—white, rural, older—it seemed, was disappearing, and dying, and killing, and overdosing. These men did seem to be in crisis, in the broadest possible sense. But it did not appear to be the end of the masculinity, at least not to me. From the moment the testosterone kicked in, nearly everyone around me was invested in educating me in how to ape the strong-and-silent stereotype of the man whose reign was “over”—a socialization that involved relentless policing by strangers and friends alike, and across gender, geographic, and socioeconomic lines. Whatever compelled these instructions, they seemed core to manhood itself, and maybe that’s why I became obsessed with chronicling the “masculinity crisis”—both the unfolding economic fallout that stemmed from a fundamentalist gender narrative linking masculinity to work, and the way I found its many echoes in my own experience of dislocation in this body. Because of my conditioning, I suspected that the “crisis” was far more complex than people understood, that its root cause was far deeper than class and race and “tradition,” that the bedrock of the crisis was inherent in masculinity itself, and therefore it encompassed all men, even the ones who felt they successfully defied outdated conventions. It was, after all, the men who read books on emotional intelligence and wore tailored shirts who often advised me, with the casual, camouflaged sexism of the urbane, to treat dating like warfare, or to dominate meetings with primate body language.

It seemed to me that being in crisis was a natural reaction to being a man, any man, even if that wasn’t precisely what anyone else meant.

I started thinking about all of this back in 2011, the year I first injected testosterone. I’d just landed my first full-time journalism job as an editor at a newspaper in Boston, following the headlines with macabre curiosity from the United States to the United Kingdom and eventually as far east as China. In the United States, the story morphed quickly into the now-familiar tale of class and generational stratification: Poorer men were being “left behind” by the rise of education rates for women and the trend away from marriage in lower income brackets.

Meanwhile, well-off “makers” in cities dressed like lumberjacks and dabbled in bespoke artisan crafts to reconnect with old-fashioned, hands-on work, but with attitudes toward masculinity that many men insisted were radically different from previous generations. Millennial guys seemed, to the sociologists and anthropologists who studied them, to have attitudes toward women that portended a new era of equity—especially at work. But the reality was, indeed, far more complicated. Later surveys and studies would suggest that Millennial men as a whole turned out to be as “traditional,” and even less egalitarian, in their attitudes toward gender as their fathers—which made experts eventually posit that growing up with fathers impacted by the masculinity crisis made them more, not less, resistant to gender equality.

But that came later. Back in 2013, about a year before that disappointing story began to emerge, I lost my journalism job in Boston to massive layoffs. I was living cheaply enough to subsist on freelance and contract work, so I chose optimism, casting around for story ideas about men who seemed to be using the crisis as an opportunity to challenge the negative aspects of manhood. And they were out there: Men were more engaged fathers, experts said. Rap stars and pro athletes came out. Bromantic comedies about the platonic love between friends beat out traditional, more sexist buddy comedies at the box office. I needed those stories, needed those men, taking solace in the idea that I wasn’t the only guy seeking a different answer from the one I’d found in the models that had shaped me, growing up in a small town outside Pittsburgh.

But the more I felt at home in my body, the more my discomfort with what was expected of it deepened. Later that year, I moved to New York and spent most of my free time on terrible first dates I couldn’t afford with women I couldn’t figure out. I wasn’t sure how to tell them I was trans, or if I even should, but I also didn’t understand how to transcend the surprising traditionalism that masked our every interaction.

As I struggled to make sense of my place in the world, the economy improved and certain cultural shifts around fatherhood in particular did seem to take hold, but the masculinity crisis raged on. Men I grew up with killed themselves. As an opioid epidemic surged, social media bifurcated Americans. I could see the splinter in my own feeds, where I found a reader-ship for my stories, but trolls tweeted at me in response to nearly everything I wrote. “You’re not a man,” they said, over and over. “And you never will be.”

It was 2015. Everyone told me to “not read the comments,” but it all—the policing, the dating, the sexism, the trolls, the Millennials, the opioids, the “makers”— it all seemed connected. I couldn’t shake the idea that this larger masculinity crisis held in its bitter center a truth that reflected something important and terrifying about what we talk about when we talk about men. All men. Something bigger than a generation, or a political moment, or an economic crash—a story about masculinity that we all, every one of us, has been taught to believe.

• • •

“Maybe, instead of looking for the men you want to be, you need to face your worst fears about who you are,” Jess said, early in our courtship. She wondered if my notions of masculinity were unrealistically “romantic.” I wasn’t so sure she was right, but her invitation to examine my fears so terrified me, I tried to avoid thinking about it, until my run-in with the man on Orchard Street clarified her wisdom. There he was, finally, my awful mirror: when he balled his fists, I balled mine. If you happened upon the scene and didn’t know me, you’d be hard-pressed to identify what made us so different, and you’d be right.

“Hey!” the man shouted, and that wickedness coursed through me even as I marshaled the self-control to turn and walk away, tracking his ever-louder footfalls, leading him toward Seward Park, where at least there were parents and children playing on the slides, New Yorkers who, I hoped, would tend to me if I was knocked to my knees in front of them.

Moms, I mean.

“Hey!” he shouted, as we approached the corner, and then, more menacingly, “Asshole!”

A group of roughhousing boys, quieted perhaps by a real-life scene of what they playacted, turned to look.

I was embarrassed. I wanted to be held. I wanted to drink tea in a living room warm with sunlight in a world I could understand. I wanted a life I would never again have. I looked at the man with the sweaty forehead and dusty beard, and I let an acidic rage bloom in the place of all I’d lost, coloring my tone such a ragged mess I didn’t recognize my own voice. “I. Did. Not. Take. A. Picture. Of. Your. Fucking. Car.”

He backed away with his hands up. “Okay, okay,” he mumbled. “Jesus.”

I leaned against a wall. Something had to change.

• • •

In my corner of New York, the masculinity crisis was increasingly taken for granted—something happening to other men, far away.

“Men keep trying to fight me,” I told my friends, my brother, my coworkers after that day on Orchard Street. Most people shrugged. Weird, they said. What could you do?

It was 2015, when I began this book, and we were looking toward the future. When I said I was writing about masculinity, people didn’t react as they did at the start of the crisis—more and more, they smiled politely and changed the subject. I understood. A lot of people felt as if we had been talking about a certain kind of man for long enough. It was easier to believe that we lived in the age of progress, and that progress would just keep moving us all forward on its tide. President Obama illuminated the White House in rainbow light, after all, and Beyoncé was on the cover of Vogue’s September issue. Transparent was a critically acclaimed show on Amazon, and Hillary Clinton had just officially announced her intention to become the first woman president of the United States. But underneath the smooth momentum, I could feel the rumbling, like plates moving.

It occurred to me that maybe it wasn’t just being trans, but the precise timing of my transition that allowed me to see what other people didn’t. The rules that newly defined my life were not futuristic: Do not let yourself be dominated. Do not apologize when you are the one inconvenienced. Do not make your body smaller. Do not smile at strangers. Do not show weakness. The kumbaya narrative of a world without borders, driven by change, wasn’t the whole story. I could see it every day, in the way my body got shaped, read it in the headlines, feel it in the edgy encounters I had with man after man: something terrible was always already happening.

Maybe, instead of looking for the men you want to be, you need to face your worst fears about who you are.

Soon enough, nations would be beset by a wave of authoritarian leaders, including the election in the United States of Donald Trump, a man whose campaign for higher office against the first female major party candidate was, in many ways, an open referendum on bodies and the rules regulating them, especially the recent social and political gains made by those whose existence challenged the long reign of white masculinity: women, trans people of all genders, and people of color. Soon enough, a wave of harassment and assault allegations would topple Hollywood executives, actors, and titans of industry. These men weren’t dinosaurs. They were everywhere, all along.

But back in 2015, in the weeks and months after that day on Orchard Street, as friends shrugged off my question, the crisis within and beyond me continued its slow boil. So I began to look for a new way to shape my own becoming. I was itchy, compelled in the same way I’d felt, pre-testosterone, when I saw a vision of a man bearded and shirtless, sitting at some future kitchen table, and I knew in my gut that it was my destiny to become him.

Why do men fight? I began to see the question as a proxy, a starting point, for what I initially thought of as a very personal experiment: If I shone a light on the shadowy truths about how I’d come by my own notions of what makes a man, could I change the story of what being a man means?

Which is how I found myself, less than two months later, boiling a mouthguard in my kitchen, priming it for my bite.

• • •

The brutal intimacies of boxing—between coaches and fighters, and even between opponents—are part of our cultural narrative, and I imagined they might help me address the question of male violence with some ritual and containment. I was a longtime fan, fascinated by Mike Tyson’s steroidal press conferences, and the Rumble in the Jungle and the Brawl in Montreal and the War, but mostly by the literary quality to what struck me as a compelling allusion and troubling metaphor for my own experience of manhood: two men, stripped and slowly ground down to their essences in front of a blood-thirsty crowd in a wounding ballet of fists and a losing battle with time. There was an honesty in that violence, a kind of grace that both referenced and eclipsed my more toxic notions of masculinity. I couldn’t think of a more visceral way to face it.

I’d pitched a feature story about the men who elected to fight in white-collar charity matches, and the guys who trained them, to my bosses at Quartz. Through a buddy who’d done the same fight a couple years before, I signed up to train for a cancer-fighting charity called Haymakers for Hope.

As I was nervously loading up on sweat-wicking gear and boxing shoes, I couldn’t have guessed how much my struggle with toxic masculinity would eventually lead me to zoom out, asking questions about my own body in space that required me to chase increasingly urgent economic, environmental, and political implications of the masculinity crisis I’d suspected was connected to me, all along.

But, then again, I had been reading the psychologist Carl Jung, who, after World War II, long consumed by the question of what made people evil, or complicit in evil, settled on a single, elegant explanation. He believed that ostracizing any aspect of the human experience, however ugly, created a “shadow” of our rejected bits that we drag behind us. If we do not see that the shadow belongs to us, we project it onto others, both individually and as a culture. To face and own what most disturbs you about yourself, Jung believed, is among the central moral tasks of being human.

I began this book because, though I could not articulate it then, I understood that I could not know why I wanted to break that man’s teeth on Orchard Street without understanding, in turn, why he wanted to break mine.

In pursuit of that night under the bright bulbs of the most famous boxing ring in the world, I spoke to executives and academics, but I also interviewed my siblings, and Jess, and the men who punched me in the face and allowed me to hit them back. I tried to look at masculinity with a beginner’s mind, and I asked questions even when I was embarrassed, or when my mouth was full of blood, or when I was afraid of looking stupid, or lost, or weak. Especially then.

Why do men fight? This is the story of how I found the answer.