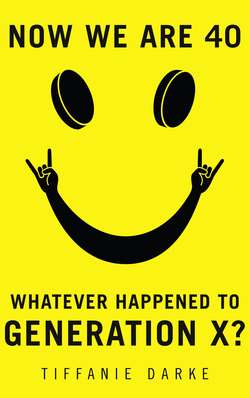

Читать книгу Now We Are 40 - Tiffanie Darke, Tiffanie Darke - Страница 12

Four Go to Ibiza

ОглавлениеIn the summer of 1987 London’s nightlife scene was fractured. The Leigh Bowery performance art scene at the Blitz was burning itself out and the music of soul boys, hip hop, rare groove and pop was progressing independently of each other. Four friends who worked the scene as DJs and promoters decided to celebrate a birthday with a trip to Ibiza. The birthday was Paul Oakenfold’s, and his friends were Danny Rampling, Nicky Holloway and Johnny Walker.

They had been to Ibiza before but had never experienced the ‘after hours’ scene that people were beginning to talk about – the places people went to after the clubs had shut. They had heard of a place called Amnesia, an old farmhouse out in the countryside that was an outdoor club for those in the know. It opened at 3 am and went on till noon the following day. They had also heard about this new drug, ecstasy. None of them felt inclined to take it until they got there – but under the stars, in the warm summer air, ‘hearing this amazing mix that DJ Alfredo was playing’, and finding themselves in the middle of a scene not even they could have anticipated, everything changed. ‘I was really anti-drugs in those days,’ says Nicky Holloway. ‘I used to chuck people out of my clubs for having a puff. But everyone round us was doing it, and it looked like so much fun. I was like, alright then.’

‘There were no laws: people were making love on the dance floor, drinking and dancing, taking litres of liquid ecstasy between them,’ reported one of the barmen at Amnesia, a German by the name of Ulises Braun. ‘It looked like a Federico Fellini movie; every personality was different. Everyone was dressed up. I dressed like d’Artagnan, in high boots.’

In the middle of the dancefloor was a mirrored pyramid, around the edges were bars and chill-out areas with cushions and plants. It was like being in a tropical garden.

‘It was a complete revelation to all four of us,’ says Danny Rampling, ‘out there in the open air, on that dance floor on that Mediterranean island. It was all about music and hedonism, but what was so unique were the people – they were really cosmopolitan. Even the DJ, Alfredo, was a maverick on the run from the junta in Argentina. He had fled to Ibiza as a political refugee.’

‘We would never have gone to a place with 40- or 50-year-olds back in London,’ says Holloway, ‘but Amnesia didn’t have any barrier – of age, colour or country. There were people from Switzerland, Holland, Singapore, Germany, Brazil. And the music was completely different, too. It was Balearic, which means it would go up and down. There was house music, but then Alfredo would play Carly Simon or Kate Bush – things we would turn our noses up at, at home. But on ecstasy, in that euphoric club, the whole thing made sense. At 7 am, in the morning light, Alfredo put on U2’s “I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For”. It opened our ears and our eyes. Everything fell into place.’

‘All four of us changed that night,’ says Rampling. ‘In Ibiza I got my brief to do what I wanted – I wanted to play to my own crowd of people.’

‘We came back like salesmen,’ says Holloway.

Within five months of their return to London Paul Oakenfold started Spectrum, Danny Rampling started Shoom and Nicky Holloway started Trip. ‘At that point the London club scene was based in the past – funk and soul and things,’ says Rampling. ‘When house music came along it completely changed everything. It was revolutionary. It brought with it a wave of empathy and unity, fuelled by one thing and another. Ecstasy, yes, but also the political and economic situation in the mid Eighties. At that time Great Britain was very depressed – there was high unemployment. A lot was changing around the world: the apartheid regime in South Africa was imploding, the Wall was coming down in Berlin – there was change going on and we all were experiencing it.’

Shoom became a legendary success. There were 50 people on the first night and twelve weeks later 2,000 people were queuing down the street. Spectrum and Trip were similarly groundbreaking. ‘It just caught a wave,’ says Holloway. ‘It couldn’t have happened without E – let’s not pretend – but overnight it went whoosh! We were doing Tripping the Sin at Centrepoint, and everyone would empty out of the club in the morning and start dancing in the fountain, singing songs and hugging each other. The police just stood there – they didn’t know what to make of it.’

Without the internet – with only word of mouth, flyers and some helpful PR from the tabloids – the scene still went national. ‘I remember the Sun doing a story on evil acid house and how bad it was,’ laughs Holloway. ‘They had pictures from a rave at an airfield – but by putting it on the front page they were unwittingly advertising it to everyone. Everyone was thinking, “That looks fun. I’ll have some of that!”’

Every kid who dropped one of those tablets – Doves, Rhubarb and Custard, Pink Cadillacs, Mitsubishi; they were given cutesie names to describe the experience they gave – felt the ‘shoom’ as the rush tore through their body, and the transitory, almost hallucinatory feeling that they had found the secret key to a better world, one where everyone could come together and live in sweet harmony.

‘There was a lot of spirituality in the music. Songs of hope, like Joe Smooth’s “Promised Land”, were gospel-driven records. All these records out of Chicago and New York were made by former disco producers who were really into gospel and great songwriting, and that fuelled all this optimism and hope and unity – and change. With everything that was going on, this was quite overwhelming to some people.’

There were a lot of sweaty hugs and ‘I really love you, man’ uttered in the early hours of the morning on heaving dance floors, often just to the stranger standing next to you – whoever they were. ‘You’d go out with one set of friends and come home with another,’ says Holloway. ‘It smashed down the walls,’ says Rampling. It helped everyone feel everyone else’s importance, it put us all on an equal footing.

There was one apocryphal moment in Shoom when a punter opened a page in the Bible and insisted that Daniel – Jesus’ disciple – was in fact Danny Rampling. ‘This is you! This is you! This is what’s happening now!’ he insisted. ‘These people were using a lot of LSD,’ grins Rampling.

Parts of the country that did not have access to nightclubs were just as involved – in the form of illegal raves conducted outside in fields or inside in disused warehouses. They were staged by the traveller community, do-it-yourself DJs, sound systems and party collectives, as the craze spread like wildfire through the towns and country.

‘I was living in the Somerset countryside at the time,’ says the fashion designer Alice Temperley. ‘It was like discovering this underground culture. The whole thing started with the music and that sense of liberation, that you felt like you were able to express yourself. It was like being swept up in a cult-like movement, you felt you were part of something, part of a pack. I was about fifteen or sixteen, and in some sense it was just kids wanting to misbehave – getting into a car and ending up in a convoy in some field and partying until sunrise – but it was very seductive.’

A couple who straddled both scenes, fields and clubs, were Pearl Lowe and Danny Goffey. Pearl was a fixture on the London club scene, Danny was a schoolkid in Oxford. Both went on to form successful bands and become part of the tapestry of Nineties culture, but this was where it started.

‘I was expelled from Wheatley Park Comp in Oxford just at the start of the illegal rave thing,’ says Danny. ‘The sound system Spiral Tribe was going all round Oxfordshire. I didn’t tell my parents I’d been chucked out of school. Instead I signed on and started to hang out at travellers’ sites, going off in convoys to Gloucestershire or wherever the next rave was happening. I went to stay in a caravan with some travellers called Chris and Julie. I used to smoke dope with them and listen to techno. They had an Alsatian dog called Skewer. It was a bit like a second home for a while. I started a band called the Jennifers. Chris played guitar; he was in a band called White Lightning after the acid. We used to sit up and play really mad music, lots of Hawkwind and rave. He was into thrash metal – that was the crossover of those two scenes – sort of crusty dance.’

‘I was putting on nights in Chelsea with two friends,’ says Pearl. ‘The three of us hosted these raves for this dodgy guy. We would go up the Kings Road with flyers, and he would make loads of money – there were queues down the road. We’d go to Subterrania on Friday nights and my friend Jasmine Lewis, who was quite a big model, and I would dance on the stage. Joe Corré, Steve Strange, Jeanette Calliva were all there. Then there was the Limelight that everyone went to, Boy George and Rusty Egan and Philip Salon. Es had just come out, so we would end up at Ministry of Sound at 5 am.’

‘In London things were trending quite quickly,’ says Danny. ‘Where I was, there were no clubs, or one in Oxford. So when that all kicked in it was a scene like punk – everyone who was my age got really into it. Everyone who could drive would go off on these two-day adventures. Then the band started kicking off, and Oxford seemed quite small, and I wanted to move to London. We got signed and then I met Pearl and went to live in her house.’ The tribes started to move together.

Before it became polluted by gangs and bad drugs, marketing and commoditisation, the house music scene had a very positive effect on society. It quelled the football terraces, brought down class, sex and race barriers, and imbued an entire generation with the belief they could go out and express themselves, do something they believed in. ‘It was a Do It Yourself culture,’ says Rampling. ‘We created our own industry and scene, which allowed people to create their own jobs and follow their dreams, whereas punk, which certainly had great energy, had been all about anarchy – leave your job and stick two fingers up. It was very destructive. Acid house, by contrast, was all about positivity, hope, optimism and bringing people together.’

The DIY nature of the movement – that it was happening despite government and law – was profoundly influential. Why trust and accept the structures around you, if they don’t trust or accept you?

The size of the scene eventually became too much to ignore, and led to the Criminal Justice Bill. Bizarrely wide-ranging, the bill sought to criminalise offences previously termed as ‘civil’, giving police and the courts greater powers to prosecute. It included everything from extending the definition of rape to include ‘anal’, to the criminalisation of the use of cells from embryos and foetuses. However it drew the biggest objection for its response to the free parties put on by the traveller community, whose occupation of common ground was causing middle England some distress.

Plenty of Gen X youth were extending their summers of love at these parties, the most famous of which was a week-long festival at Castlemorton in Worcestershire. In May 1992 tens of thousands of travellers had already amassed in the area for the Avon Free Festival, which the police cancelled, fearing a noisy party that would get out of hand. All the groups ended up settling on Castlemorton Common. As the sound systems cranked up, the police were left powerless to act, marooned helplessly at the bottom of the hill. The media swarmed around the event, which had now become something of a spectacle, but their headlines and front-page coverage only served to swell the numbers.

These free parties were quite something when you consider they were all organised in the pre-internet and pre-mobile world. Living in Oxford at the time, I also got caught up in this scene, and it was thrilling to be a part of it. Word would get out to meet at service stations on B roads, sketchy directions would be distributed by Chinese whispers, shouted through car windows at traffic lights – as an overloaded Vauxhall Astra playing house music off a mix tape on a tinny stereo would pull up beside you, clouds of spliff smoke pouring out of the windows. We would sometimes just literally head off into the dark, following the tail lights of the car in front, listening out for the distant thumping of a sound system.

Finally, when it didn’t look like we could get any closer, we would abandon the car and head across fields towards the noise, blood pumping through our bodies in expectation of the revelry ahead. There was such an illicit thrill to the whole thing – the idea that there was this self-created network, unchecked by the authorities, creating a scene beyond their control, connecting people and beliefs through ‘ley lines’ and ‘energy centres’. We were another, alternative lifestyle, a different community; this was our new world, beginning under the moonlight, in fields, warehouses and squats all over the country. As the sun came up, our new best friends from the night before would still be dancing on the top of cars, grinning from ear to ear with the innocent joy of discovery, drugs and the sense of being part of something new. It was huge, and it was beautiful.

It reached its apotheosis in that May of 1992 as the police looked on at the ravers, crusties and their dogs bouncing around on the top of Castlemorton Common. All the sound systems amassed together that week – Spiral Tribe, Bedlam, Circus Warp and DiY. Me too, although my memory is, funnily enough, patchy. I do remember the generator running out of power at one point and some dreadlocked dudes doing a whip round with a bucket. Some time later I saw the same dudes chasing a guy down the hill before beating him up viciously with fists and sticks. I think he had tried to nick the bucket of money. That bit definitely wasn’t beautiful.

The public–police stand-off at Castlemorton provoked the Criminal Justice Bill – in particular Section 63, which banned ‘sounds wholly or predominantly characterised by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats’. This lit up the music industry. The band Autechre released a three-track EP labelled ‘Warning: “Lost” and “Djarum” contain repetitive beats’. Orbital released a mix of its track ‘Are We Here?’ that it titled ‘Criminal Justice Bill?’ and which consisted of four minutes of silence. The Prodigy included a track ‘Their Law’ on their album Music for a Jilted Generation, which was introduced in the sleeve notes with: ‘How can the government stop young people having a good time? Fight this bollocks.’ Meanwhile Dreadzone released the single ‘Fight the Power’, which sampled Noam Chomsky urging people to think about ‘taking control of your lives’, and advocating political resistance. The ruling party was as culturally divorced from its youth as it was possible to be.

The bill didn’t just target ravers – the legislation also attacked hunt saboteurs, squatters and football fans. Essentially it amounted to a judgement on people’s lifestyles – which enraged us. It repealed the councils’ duty to provide permanent sites for travellers; police would have new powers of stop and search; the right to silence would be affected; and the criminalisation of ‘disruptive trespass’ had consequences for squatters, travellers and protesters alike. Uniting in protest, formerly unrelated movements began to come together in coalitions: students, trade unions, sound systems, traveller communities and direct action groups.

Three marches were planned in central London, the first two of which passed peacefully, with Tony Benn standing on a box in Trafalgar Square. Raves in London squats and on Wanstead Common took them into the night. The third ended in a riot. Tear gas was deployed, civilians were beaten up by police, dogs died, and any impression the groups had given the establishment that they were a civilised bunch with a civilised point of view was seriously damaged.

Once the bill came into effect, the free party scene withered. Instead, the right to party went overground and became a thriving industry. Nightclubs, DJs and festivals were the ultimate winners. Festivals still loosely embed political and socially conscious messaging into their line-ups, in a nod to the DNA of the scene that birthed them, but actually they are more about having fun and taking a break from normal life than raging against the machine. Your alternative lifestyle in one three-day £150 ticket. Sponsored by Vodafone. If you go to a festival now you are part of an entertainment culture, with nice bathroom facilities, wrist bands, glamping and fancy cocktails. It’s a long way from those crusty sound systems and cans of Strongbow. Those sound systems headed into Europe, making way for Paul Oakenfold, Carl Cox and their progeny – Calvin Harris, David Guetta, Tiesto – to embrace a life of money and fame.

Ibiza went on to flourish. Surviving the scandal of Ibiza Uncovered, the television series that exposed the messy ‘Brits on tour’ years, it has remained a hedonist’s destination. It continues to supply a 24/7 smorgasbord of distraction, and when the low-cost airlines opened it up to weekend clubbers, no one ever caught their flight home. It was like a super, sunny, brown-limbed version of Castlemorton, with glamour, glitter and sand.

These days Ibiza is mostly off limits except to the super rich. It has risen above the raving riff-raff by hiking prices, and much of the partying takes places in expensively built private villas rather than the clubs. Many who built and bought those villas passed through the raving nineties – Ibiza’s hippie values and dance music culture suit their millions very well, even if they have built their own private nightclubs underneath their tennis courts. They no longer smile at strangers as the sun comes up, but at each other on board a yacht back from Formentera where they have just blown a grand on a rosé-soaked lunch at the see-and-be-seen beachside restaurant.

For the rest of us, there is ‘glamping’. Evolving the notion of abandoning yourself to the countryside for a night of hedonism, Generation X has consciously curated the experience – applying all the signifiers of cool to the original idea of striking out and leaving societies and communities behind. Being out in the open, ignoring the rules around night and day, creating your own environment to suit you, somehow morphed into £400 bell tents and Cath Kidston bunting. ‘Wild’ camping converged with the ‘free’ party experience, and we styled it up with duvets, double-lilo blow-up beds, tealight chandeliers and yurt hotels to make it as luxurious as possible. If your urban experience traps you Monday to Friday, you can load up the car on a Friday night and head off with your mates (and kids) for a weekend of (relatively) comfortable escape. Someone can always bring a sound system.

Some of the activist momentum was retained, however. ‘I remember being in Shepherd’s Bush when Reclaim the Streets took over the roundabout,’ says Martha Lane Fox. ‘Which I guess was to do with politics loosely, but it might just have been a massive rave. I’m not sure we had a sense of social purpose. We didn’t want to change the health service or change governments. We were just like, Fuck Thatcher, here’s a new way of being.’ However anti-establishment and vaguely political the movement felt, it was more a feeling that we were different from the world we had been born into, and that we were going to express ourselves differently. ‘We were culturally ambitious, but not politically,’ says Martha. ‘We went because it was a laugh, not because everyone was really up in arms.’

The Criminal Justice Bill succeeded then – despite the protest. It forced music and dance culture to be legalised, regulated and commodified, so it could be moderated and taxed. But it didn’t kill the music. Far from it – the Nineties were a period of incredible musical creativity, producing wave after wave of new music culture, from rave to Britpop to house to trip hop, to acid jazz to trance and drum ’n’ bass.

Much of that was to do with the growing multiculturalism of British society, and all the glorious influences that brought with it, in music, politics, fashion and community. Britain’s second generation of immigrant culture was just coming of age, and the social take of what those kids were offering up was absolutely the height of cool. As June Sarpong, a Ghanaian who grew up in Walthamstow, says, ‘Being in London during that time was so interesting. We were immigrants who had grown up and integrated with white people in a way that our parents just hadn’t. I was hanging out with Jazzie B and the Soul II Soul crowd at that time, and I found myself at the heart of this shift in the thinking of the city, the birth of a culture.’

Second-generation immigration culture was nowhere near the ruling elite economically or politically – but culturally they were absolutely centre. Economically, there was displacement, and violence and drugs. ‘I had a terrible car accident in 1989 that took me out of action for two years,’ says June. ‘I was hospitalised, stuck in a bed unable to move. Those big, formative teenage years were wiped out. All my friends grew up in social housing, they were doing drugs and getting wasted, things you do at that age. The accident was like a crazy intervention from the universe because I missed out on all of that. That’s the reason I don’t drink, or smoke, or do anything now, not because I’m judgmental but because the time I would’ve started I was ill. By the time I got better, I’d spent a lot of time on my own thinking in a way that would keep me from going mad. I had had to grow up.’

When June came out of hospital, Soul II Soul took her under their wing and got her a job at Kiss FM. ‘It was when Kiss had just become legal and they had all of the cool DJs from the illegal days – Trevor Nelson, Judge Jules, all those guys. I started working with them, going to Ibiza and Manumission. It was crazy, I used to go out dancing Thursday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday, out till 4 am and still manage to get to work on Monday!’

Kiss was the platform for all the new music coming through, breaking acts like Jamiroquai and providing a platform for labels like Acid Jazz (set up by Gilles Peterson to promote the music he found to play in the back room in Paul Oakenfold’s club). ‘The tide had changed,’ says June. ‘Kiss was a legal radio station playing the kinds of music our generation wanted to listen to. It went on to completely change the content of Radio One, and that brought cool into the mainstream.’

Scenes were taking off in Manchester and Liverpool too. Down in Bristol the Wild Bunch sound system birthed Massive Attack, Tricky and Bristol’s trip hop scene. Nellee Hooper moved to London and became a producer for Madonna and U2. Meanwhile Bristol University was bringing in a bunch of white kids from privileged backgrounds and mixing it all up. Ben Elliot, the Etonian who went on to found the luxury concierge company Quintessentially, got his first taste of clubbing in Bristol. Before he went up, he was working at the Independent; Massive Attack had just released Blue Lines and a copy had come in for review.

‘The Independent was brilliant at that point. Their Saturday Review magazine was running all these great, edgy black and white photos, reflecting a lot of what was going on. When Blue Lines came in I remember thinking, “That looks cool,” and nicking it and thinking it was incredible. Then I arrived in Bristol. Even though I went there with no friends, because of this scene I suddenly met masses of different people. I met a huge Pakistani guy from Somerset who sells furniture now. Another guy was a mature student who was really in with 3D and Tricky. I began to put on club nights and we’d get Daddy G [of Massive Attack] to come and DJ. I think at one stage I even had a pair of silver trousers. There were shops on Park Street in Bristol where everyone would go to get kitted up for Friday or Saturday night.’

It didn’t take long to spread north. ‘When I was 16 and growing up in Wakefield I remember going out to the local club, where they played terrible music – Stock Aitken Waterman,’ says Richard Reed. ‘Everyone got really drunk and I remember seeing this guy getting a glass smashed in his face. Later that night I saw the same guy in a kebab shop, still with the blood running down his face. It was dripping into his kebab, and he was eating it. No one was having any fun, it was all drunken aggression. A year later I went out again and the music had changed, everything had changed. Everyone was happy – smiles on their faces, hands in the air. House music had ushered in some kind of difference.’

The son of a nurse and a bus conductor, Reed was surprised when his school suggested he apply for Cambridge University. ‘I wanted to go to Nottingham because that was where all the best clubs and DJs were. I thought Cambridge was going to be full of posh people talking about rugby. I got to Cambridge and guess what? It was full of rugby blokes singing rugby songs, listening to terrible music. Everything I feared. I thought, we need a bit of house music here. I met Adam, from London, who loved the acid jazz scene, and this guy John and us started to put on house music nights. We realised we were having more fun organising them than the people who were queuing and paying to come in – at that point we realised we’ve got something here, this is what we should do.’ The three of them still work together today.

This time in our lives taught us influence can lie with the individual rather than the organisation. It empowered us, made us question the establishment. ‘The Criminal Justice Bill and the Poll Tax riots made everyone realise you can’t keep on telling us what to do,’ says Reed. ‘We can be subversive, question the status quo, do things differently from the way they have been done before. The Nineties roughed things up a bit – you couldn’t go out and dance all night in strict fashion, you needed to be comfortable in trainers. There was a bit of darkness going on with the political unrest and that helped people question things and reject the choice architecture.’

Cool, which we got from music, fed into fashion, film and everything else that sprang out of that scene. Cool was our possession, we loved it, nurtured it, crafted it. ‘Contrived it, yes, but that’s because we actually considered it,’ says June. ‘We cared. It didn’t matter what music scene it was, whether it was Indie, Blur or acid jazz, all of them were cool. You just wanted to be part of them, didn’t you? I wanted to be friends with Oasis and Meg and all that lot, they were just so fricking cool. Still are!

‘I think the legacy of that cool is, our generation will be forever young. My mother was late thirties, forties, at that time, which was like an old woman. Whereas we will be like this for another 20 years. I don’t think that’s the same for the younger ones. I think we’re going to catch up. When we’re 60 and they’re 40, I don’t think there’ll be much difference at all!

‘Also we monetised cool, exploited it, which is a good thing because for so many years interesting artists have been broke. Thank goodness the Damien Hirsts and Tracy Emins made loads of money. Great, why not? But at the same time, it meant that we lost some of the really important changes. And one of them for sure is making politics interesting for a disengaged group.’

With cool comes irony, and in the end irony is a great dehabilitator of progress. Irony eventually means you believe in nothing – it leads to nihilism. Maybe the reason we dropped the ball politically is because we couldn’t take anything seriously – even ourselves – in the end. The political denouement to all of this was starkly illustrated in the Brexit vote. The inclusive, liberal, multicultural society we thought we had built was rejected by just over half the country. Brexit was a shout from those whom this society did not benefit – or who did not understand its benefits. Those for whom multiculturalism was not a benevolent positive force; for whom the metropolitan acceleration was too fast and too self-oriented; whose sense of nostalgia and nationalism extended back to before this time. There’s a job to do now, to bring those two halves together, and a lesson for Generation X that when cool becomes too exclusive, it writes itself out of the system.

But politics aside, we had learned a lot from the dance music revolution – it was time to make a living out of what we had learned.