Читать книгу Bent Street 3 - Tiffany Jones - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

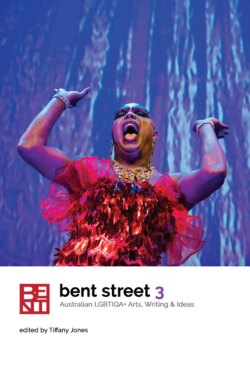

OUT ON THE FRINGES STEPHANIE AMIR

ОглавлениеMy legs and hands become increasingly paralysed for three days and four nights before I decide to go to a doctor. By then my feet are cold, lifeless lumps. Bending my knees even slightly causes my legs to sear with pain and collapse, but somehow it is not until my hands are too weak to pick up my morning cup of coffee that I admit to myself that something is very wrong.

In the emergency ward, I have blood tests and muscle tests and a test for the flu. Later the doctor orders a lumbar puncture, which involves sticking a giant needle between my vertebrae to extract spinal fluid. He asks me to curl into a ball and hold still.

To keep my mind off the pain I focus on memories of doubles-trapeze training, imagining myself bracing my abdominal muscles and holding tight to the forearms of my flyer so she won’t fall. Surely if I can flip a woman through the air, I can hold tight in a ball.

Twenty minutes later, the neurologist comes in with my diagnosis. ‘You have Guillain-Barré Syndrome.’

‘Nah,’ I say, trying to be funny. ‘I ordered an acute potassium deficiency, so that you could give me one injection and my legs would work again.’

‘Well,’ he responds with a raised eyebrow. ‘We’d narrowed it down to Guillain-Barré, Multiple Sclerosis or spinal tumours, so from that list you got the pick of the bunch—at least you’ll recover.’

Not everyone does recover from Guillain-Barré. It’s an autoimmune illness that attacks the nerves and the myelin sheaths that protect them, causing ‘ascending paralysis’ that starts in the hands and feet then gradually ascends up the body over hours, days or weeks. For some people, their whole body, including their lungs, become completely paralysed. There’s no reliable cure, so it’s mostly just a matter of keeping the patient alive until the acute phase is over, then months of rehab while the myelin sheaths grow back. Most people survive, but usually their bodies don’t go back to how they were before.

I went to sleep in the Intensive Care Unit as the paralysis crept through my thighs and across my hips, through my fingers and towards my wrists. I could still move my arms and torso, but knew that by morning they might be cut off from my brain too.

An hour later, I woke up freezing cold and shaking violently, my blood pressure plummeting. Terrified, I cried out and begged the nurse for more blankets. She turned off the drip (intravenous immunoglobulins, an immune-system transplant) and gave me some kind of opioid.

Eventually the shaking stopped. As my body temperature returned to normal I felt hot under the mountain of blankets and absent-mindedly kicked them off. The nurse and I both looked at the blankets, then my legs, then each other. Then I was crying again, but this time with relief. The nurse said in twenty years working in ICU, she’d never seen such a quick turnaround of a Guillain-Barré patient.

I thought the worst was over, and the most dangerous part was, but I’d entered a messier, more enduring stage. My friend Ben came to visit me and quipped: ‘You’re already a young queer woman with a baby and a Middle Eastern name. You didn’t need to add ‘disability’ to your list of minority groups.’

When I got home from hospital, dinners arrived on our doorstep each evening. At first, showering and dressing used up almost my entire day’s energy so I spent the rest of it lying down and reading on the bed, couch or banana-lounge. I couldn’t parent beyond letting my eight-month-old crawl on or around me, so was totally reliant on my partner. A month later I was tanned from the banana-lounging and able to hobble around the house. ‘You don’t look sick,’ some friends said, meaning it as a compliment. But I was. I couldn’t even stand up to wash the dishes without collapsing in a feverish heap.

Two months after leaving hospital my in-laws visited from Canberra and we went on a daytrip to Healesville Sanctuary, because we knew my daughter would love the bird show. I still couldn’t stand for more than a few minutes at a time so we borrowed a wheelchair. People smiled appreciatively at my father-in-law as he pushed me around, but either ignored me or gave a well-intended but infantilising smile, like someone might give a small child sitting obediently in her pram.

Those patronising smiles jarred with my sense of self, and I wondered how long other wheelchair-users lasted before yelling at people. ‘This isn’t all that I am!’ I was tempted to shout, ‘I’m a politician and community leader! I was elected with the highest primary vote in my ward! I am responsible for millions of dollars of public infrastructure! I’ve already fulfilled five of my six election commitments in my first year! LOOK, I CAN SHOW YOU OUR STRATEGIC PLAN ON MY PHONE RIGHT NOW!!’

Instead I stayed quiet. Rationally I knew that a person’s worth wasn’t related to their career achievements. Yet despite my frustration at the stereotyped expectations of what a person with a disability should look like or how they should act, I felt bound to fulfil them. On the days I was out in a wheelchair, I felt like I shouldn’t stand up in case someone thought I was ‘faking it’. When I returned to work I used a walking-stick, not because it made walking easier but because I was convinced that otherwise no one would believe I really did need the tram seat, or to sit down for the duration of any networking function.

I felt disabled in the sense that I was not physically able to live as I did before, but also didn’t feel disabled ‘enough’ to consider myself a ‘real’ person with a disability. It started to mess with my head. Seeking clarity I messaged my friend Brigid, who has albinism and also understands people and humanity in a deep way that I, as a science-minded feelings-phobe, do not.

‘Oh, everyone feels like that,’ she said. ‘I feel like that. I have a mate who has cerebral palsy and most other people would consider her to have really significant disabilities but she still feels on the fringes of the disability community.’ I didn’t know how to respond. The idealistic part of my brain couldn’t get past the principle of equity of access for everyone including access to community and collective identity, but the logical part wondered whether inclusion in a community required active participation and contribution. Meanwhile the frightened part of my brain resisted any challenge to my former identity.

Brigid—astute as always—shifted to a frame I’d understand better.

‘Imagine if a young bisexual woman came to you, as someone active in the LGBTIQ community, and said ‘I don’t deserve to be here because I only came out a few months ago, and I don’t feel like I’m gay enough’. What would you say to her?’

‘I’d say that that LGBTIQ community is for all LGBTIQ people, regardless of how long they’ve been out or who they’ve been with or how they identify,’ I responded.

It seemed too obvious to even bother articulating.

I mused over this in the months that followed. I’d held leadership roles in the LGBTIQ community for more than a decade and had been proud of promoting inclusion across the spectrums, but the more I thought about it, looked around me and spoke to friends and colleagues, the more I realised how—unlike me—many people in Melbourne’s LGBTIQ community felt on the fringes. I started listing the people I knew who have said they didn’t feel like they belonged: there were people who identified more strongly with other parts of themselves, people who felt like they were ‘too young’ or ‘too old’ to fit in, people with a culture or religion other than Anglo-atheism, people who couldn’t afford to go out to queer events, people for whom it’s not safe to come out, neurodiverse people, pretty much anyone identifying with the letters beyond the ‘LG’ part of the alphabet-list, and many more.

That didn’t leave many people in the middle, who felt that they belonged within the LGBTIQ community. Perhaps this meant there were even more LGBTIQ people at the fringes than in the centre. What did that mean for our community? What did it mean for any community?

I am still contemplating those questions, but I guess it just means that we all continue to live loudly and proudly—or equally valid: quietly and contentedly—from the centre of some circles and the edges of others. Inclusion is a collective responsibility, while identity is an individual decision; both contribute to the creation of culture within communities.

According to the neurologist’s definition, I have ‘recovered’ from Guillain-Barré. I can now walk, run and work fulltime, but my legs start shaking and my brain stops working properly if I sit or stand for too long, and there’s no way my hands or abdominal muscles are strong enough to return to doubles-trapeze.

I now directly tell people that I have a disability, and the reaction is almost identical to when I tell people that I’m gay. Often they flinch or raise their eyebrows in surprise, so slightly that it’s almost hidden, but not quite. Then they try to say something supportive while rapidly scanning their memories for anything accidentally-offensive or exclusionary that they might have ever said to me. Usually it’s ok. The awkwardness is the price I pay to be myself, and to improve visibility for the sake of others living at the fringes.

Being confronted with the decision of whether to embrace or reject my new identity as a person with a disability has reminded me that it’s not a binary decision: the strength with which we hold each of our identities is different for each person, and maybe even each day. Currently I am very queer, slightly disabled, a proud mum, a somewhat successful local politician, and a totally useless trapeze artist.

I bet one of those labels made you flinch, just slightly.

Stephanie Amir is a public health researcher and elected local councillor. She has been actively involved in the LGBTIQ community for many years including as a radio presenter and on the Board of Directors at LGBTIQ radio station JOY 94.9, Program Manager for Safe Schools Coalition Australia, inaugural Co-Convenor of Queer Greens Victoria, and Chair of the Sex, Sexuality and Gender Diversity community advisory committee at the City of Darebin. She lives in Melbourne with her partner and daughter.