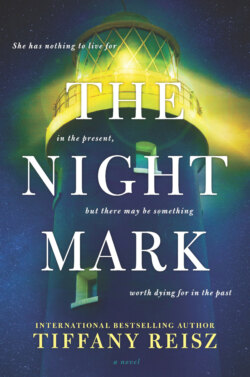

Читать книгу The Night Mark - Tiffany Reisz - Страница 10

Оглавление4

When the Beaufort County Library opened the next morning, Faye was the first one through the double doors. Unfortunately, the librarian at the reference desk was fairly new to the area, a transplant from Tennessee, and she’d never heard of Bride Island and/or Seaport Island and had no idea there was a lighthouse other than the Hunting Island Light. She suggested Faye walk down to the local tourist center with a smile and a “God bless.”

Thankfully everything that wasn’t an island was within walking distance in Beaufort. The tourist center was housed in a clementine-colored brick storefront house on Bay Street. Between last night and this morning, the wholly uncanny feeling of the lighthouse keeper’s photograph had faded from her consciousness the way a nightmare fades, mostly gone but leaving a strange, smoky pall over the day.

And yet...it was strange. Too strange to ignore, although too strange to take seriously, as well. But finding out the man’s name wouldn’t hurt, would it?

In the front window sat six watercolor paintings on easels. All of them were paintings of Lowcountry—the beach, the Hunting Island lighthouse, the Penn School...

And there it was, set off behind the others, a single painting of a solid white lighthouse and the pier that no longer existed. At the end of the pier stood a woman in a light gray trench coat. The woman faced the ocean and seemed to be holding something in her hand, something Faye couldn’t see. And behind the woman on the pier?

A large white bird perched on a pillar.

Faye froze, unable to walk away from the painting, unable to look away. The uncanny feeling returned times a hundred. First the photograph and now this...

What the hell was going on?

Faye tore herself from the painting and entered the tourist center’s front office. She found a teenage boy with his nose buried in his phone manning the receptionist’s desk. Either covering for his mother, she surmised, or doing community service for any of the usual teenage misdemeanors that deserved a punishment more than grounding but less than prison.

“Do you know anything about that painting of the lighthouse in the window?” she asked.

“Which one?”

“The one with the lady in the painting.”

“Lady painting. Um...hold on,” he said, sounding tired, hungover, stoned maybe. He wasn’t moving very fast, either, as he took a binder off a shelf and flipped through the pages. She’d been amused by the terrapin-crossing warning signs she’d seen around Beaufort with the outline of the turtle in the middle. If she had such a sign she’d hang it over this boy’s head. Then she would clobber him with it.

“Okay, here it is,” the boy said between yawns. “Watercolor. Sixteen by twenty inches. The Lady of the Light. Fifty bucks.”

“That’s it? That’s all it says about the painting?”

“Um...no. It says if you buy it, the artist accepts personal checks made out to the Historical Society.”

“I wasn’t planning on buying it. I want to know who the woman in the painting is.”

“I told you—the Lady of the Light.”

“Who’s that?”

“Some lady.”

“Okay,” Faye said, counting to ten before she murdered this boy. “What about the artist? From the angle of the painting, it looks like he or she painted it from the beach, which meant they were out there. You’re not supposed to be out there, since it’s a private island. You know anything about any of that?”

“Um...”

“I’ll take that as a no.”

“You can ask Father Pat about it, I guess.”

“Father Pat?”

“He’s a priest.”

“Why would I ask a priest about the painting?”

“Because he painted it.”

“He’s a priest and a painter?”

The boy shrugged. “What else are you going to do if you’re a priest? Not like you can join Tinder. Maybe you can. I’m not Catholic.”

“Is his number in the phone book?”

“What’s the phone book?”

Now he was just messing with her. She hoped.

“His number’s in here. Hold on.” The boy waved her off and flipped through the binder again. Finally, he found the phone number and wrote it down for her.

“Thank you,” she said.

“You should buy the painting. Father Pat would really like that.”

“I just got divorced. Took one week. Do you know how much money I had to give up to get my divorce finalized in one week?”

“You can have it for twenty-five dollars. It says so in the book.”

“Fine. Give it to me.”

Faye wrote out her personal check to the Historical Society. At least it was a tax write-off. The boy offered to wrap up the painting for her in some newspaper—she was shocked he knew what a newspaper was—but she declined and carried it back to the Church Street house. Faye wondered if sweat could damage a watercolor before recalling how much she had paid for it. As she opened the gate, Ty opened the front door. He stopped, looked at her and at the painting.

“Don’t ask,” she said.

He held up his hands in mock surrender. “I’m not asking a thing,” he said before putting on his helmet and scootering away.

Faye set the painting on her desk, propping it against the wall. Father Patrick Cahill might be an amateur, but he was a talented one. His work had a Degas flavor to it, blurry, shaky, giving the impression of the lighthouse and the outline of the woman without giving way the details. She wondered if he painted en plein air or if this had been a work of pure imagination. He could have seen the lighthouse from a boat like she had and then painted it at a different angle later. But what about the woman? What about the white bird on the pier? Either the universe was trying to tell her something, or...

She was losing her mind. Faye thought she could put money on the second option.

First, so as not to be intrusive, Faye attempted to send Patrick Cahill a text message. She composed it carefully, saying she had bought the painting of the lighthouse and the lady and admired it greatly, and if it wasn’t too much of a bother, she’d like to ask him a few questions about it. She signed her name and sent the message. She received an immediate error message.

It was a landline.

Fabulous. Father Cahill had a landline. How quaint. Now Faye understood why Hagen was so annoyed with her wanting to live in the past. She took a deep breath and dialed the number next. She hated cold-calling the man. Priests didn’t make her nervous, but she’d talked to very few of them in her time. Even when on assignment photographing the interiors of churches, she’d spent more time with the secretaries and deacons than the priests, who had more pressing matters to attend to. Father Cahill didn’t answer, but he did have an answering machine. Not voice mail. Answering machine. Would she need a time machine just to find the man?

She relayed her message to his answering machine and thanked him profusely for his time, which he actually hadn’t given to her yet. Still, this was the South, and she knew it was best to play the honey card instead of the vinegar card if she wanted a man to do her bidding.

After gathering her gear, she set out again to work. She had never accomplished anything by sitting and waiting for the phone to ring, so she drove out to Saint Helena Island. She preferred shooting her outdoor photography in the early-morning and late-evening hours, but she didn’t want to waste an entire day brooding and overthinking things. She’d done enough of that in her life.

First stop, the Penn School. According to its historical marker, Northerners during the Civil War had come to the region to start a school for the people newly freed from slavery. Faye could imagine how well that went over with the local white population. But the school, with its cream-colored exterior and red tile roof, was lovely even in the vertical noon sunlight. Faye made a circuit of the school, shooting it at every angle, even climbing a tree to get a shot of it through the branches sagging with Spanish moss. A good picture, but not good enough. She would have to suck it up and come back tomorrow morning around dawn to get the shot the way she envisioned it.

Next Faye drove down to the Chapel of Ease, or what was left of it. Four walls of tabby plaster, no roof and that was it. She took a few shots of the chapel but focused most of her pictures on the adjacent cemetery. A lovely, peaceful place until a bus arrived and belched tourists out onto the hallowed ground. Faye waited until they loaded up again and had driven off before taking the picture the way she wanted, with the chapel in the background and the cemetery in focus front and center.

The chapel’s historical marker said the place had burned in the 1860s—a forest fire—and no one had bothered to rebuild it. Now it was a ruin, a beautiful relic, perhaps more loved in its wreckage and decay than it had been while intact. Were it still an active church, Faye would have driven past it like she’d driven past a dozen other churches on this stretch of road. Perhaps Ty was onto something with his sangfroid about the imminent destruction of the Sea Islands. Those people taking pictures of the Chapel of Ease wouldn’t have set foot inside it during a Sunday service. Maybe it was simply human nature to only love a thing after losing it. Maybe they should all lose more things so they could appreciate what they had. Faye could count her possessions now on her two hands—car, camera, laptop, suitcase of clothes and shoes, phone, her beloved grandmother’s necklace and an old ring she couldn’t wear because it was much too big for her hands. Yet she wouldn’t get rid of it. Not to her dying day.

The shots of the cemetery turned out better than she’d anticipated. If they didn’t end up in the calendar, she could sell them to a stock-photo website. When she packed up her gear in the car, she had a missed call. The voice mail message said it was Pat Cahill calling and he was more than happy to hear someone had finally gotten suckered into buying one of his masterpieces. If she wanted to see him today, he’d be painting the marshlands on Federal Street, and she surely couldn’t miss him. He’d be the old man on the front lawn covered in paint.

On the way to Federal Street, Faye’s phone rang again. She didn’t want to answer, not because she was driving, but because this time she knew who was calling.

“Hello,” she said, keeping her voice even, flat, unemotional. It was easy for her to do, too easy.

“That’s all I get? Hello?”

“Hello there? That better?” she said.

“You know I’m not the bad guy, remember? You can at least fake being polite to me.”

“Hello there, Hagen. How are you?”

“God, you are really something.”

Faye heard his aggravated exhalation on the other end of the line.

“What do you want?” she asked. “I’m driving and can’t really talk.”

“I don’t want anything. I’m calling to see how you’re doing. Call it a bad habit.”

“I’m fine. Just working. How are you?”

“Working. Look, I found some stuff of yours in the guest room closet. Do you want it?”

Faye should have known he wasn’t calling just out of the goodness of his heart.

“What is it?”

“I don’t know. Do you really want me digging through your stuff?”

Faye sighed. Hagen had a gift for making things more difficult than they needed to be.

“How am I supposed to tell you if I want it or not if you won’t tell me what it is?”

“You could come here and look at it.”

“You can look in the box.”

“I don’t want to.”

“Hagen, I didn’t keep pet snakes. You can look in the damn box.”

“I think it’s Will’s stuff.”

Faye fell silent. She saw a gas station on the right, pulled in and shut off the car. It took her ten full seconds before she could speak again.

“It’s not Will’s stuff,” she said finally. “I have a few things, and his family has the rest.”

“And what about, you know... Will?”

Faye rubbed at her forehead. “I would not leave Will’s ashes in a cardboard box in a guest room closet. I scattered them in the ocean two years ago.”

“Without me?”

“I was in Newport visiting family. It seemed like the right time and the right place.”

“Without me, you mean. He was my best friend,” Hagen said.

“He was my husband.”

“Yeah, so was I.” Hagen nearly shouted the words, and each one landed on her like a heavyweight champ’s fist. A right, a right, a left and then a brutal jab straight to the solar plexus.

“I’m sorry,” she whispered. “I had to do it alone.”

“You were alone?”

“Yes,” Faye said. “I mean, except for a bird. There was a big white bird there, too. Maybe he knew Will.” She laughed at herself, and fresh hot tears fell from her burning eyes.

“You don’t sound good, Faye. Where are you?”

She wished he wouldn’t talk to her so gently. It made it harder to stay angry, and she needed her anger. It gave her energy.

“I don’t have to tell you that.”

“Jesus, do you think I’m going to stalk you or something? If I was obsessed with you I could have dragged the divorce out a couple years. It could have been ugly. I didn’t, though, and I don’t remember you saying thank you for that.”

“I’m supposed to thank you for not torturing me with a protracted divorce? Okay. Thank you, Hagen. Thank you very much.”

The pause between her last words and his next words was so long she thought he’d hung up on her. No such luck.

“I was never going to be Will,” Hagen said at last. “And it wasn’t fair of you to expect me to be him.”

“I never expected you to be Will, and I didn’t want you to be Will.”

“Because no one could be Will, right? Except Will, because Will was perfect.”

“Will wasn’t perfect,” Faye said slowly, as if speaking to a child. “No one is perfect. Especially not a man who left dirty dishes under the bed and never cleaned a toilet in his life. But this is what Will was—Will was the man who loved me, all of me, even though I yelled at him and called him a thoughtless child when he almost burned the house down trying to cure a baseball mitt in the oven. He cleaned the oven, he bought me flowers and he told me he was sorry. So no, Will was not perfect. Will was better than perfect. He was too good for this world. The world didn’t deserve him and neither did I.”

In the pit of the night when Faye was alone with her thoughts and her loneliness, she would tell herself that Will was too good for her. It was her only explanation for why he was taken from her. The only explanation that ever made sense.

“Hagen, I know—I do—that you thought by marrying me you were honoring Will, doing what he would have wanted you to do, doing what he would have done in your place. I thought so, too. But it was a mistake.”

“I kept you from killing yourself for nearly four years and you call that a mistake?”

Faye shrugged, shook her head and remembered the night Hagen had taken the pill bottle out of her hand. By the next day every gun, knife and pill in the house had been locked in a safe.

She didn’t have the heart to tell him half the reason she’d had that pill bottle in her hand was because she’d married him.

“Hagen, I really have to go.”

“Can I ask you one thing now that’s it’s all over? One question, one answer. I think you owe me that after four years of marriage and carrying my child and eating my food and sleeping in my bed and living in my house and taking my cock without complaint all that time.”

Faye sighed. She’d been pregnant for a mere six weeks three years ago and Hagen still talked about that lost pregnancy like she’d given birth to a living child who’d died in his arms. He’d lost children. Faye had lost herself. They couldn’t even grieve together.

“Faye?”

“Ask,” she said. “But don’t get pissed at me if you don’t like the answer.”

“Did you ever love me?”

“I tried.” Faye closed her eyes, and twin tears rolled down her cheeks, scalding hot on her cold skin. “I swear I did try.”

“So no?”

“No,” Faye said.

This time when the silence came she knew Hagen had hung up.

Faye hated this part, hated when it hit her full body like she’d been thrown against a wall and nothing could stop her from feeling everything she didn’t want to feel. Her chest ached and her face, too. Her throat tightened like a strong man’s hand was clutched around it, squeezing. Her stomach roiled like boiling water. From her feet to her guts to her heart to her eyes, she ached with pure unadulterated panic. She hadn’t had a panic attack since before Will died. But she remembered this feeling, this vise on her chest, this unbearable urge to run away, to scream, to fly and to fight. She’d tumbled headfirst into the pit, and nothing could get her out of it—not a rope or a pickax or her own bare hands clawing at the dirt walls.

She lowered her head to the steering wheel and squeezed the leather as hard as she could. In her twenties her panic attacks had been triggered by her student loan debt combined with her erratic income from freelancing. One bill could send her spiraling into the cold sweats, nausea and a sense of being choked to death by an invisible hand. Pills helped a little, but nothing helped more than Will putting her on his lap and holding her as he rubbed her back.

“Breathe, babe. In and out,” he’d say, his voice strong and calm as she gasped and swallowed air. “It’s not the end of the world. It only feels that way. We’ll just be poor,” he would say to make her smile. “We’ll live in a cabin in the middle of nowhere with no electricity or running water. We’ll smell horrible. We’ll grow our own food. We’ll have cows and chickens and no TVs. We’ll have so much free time, babe. I don’t even know what we’ll do with all that free time... Wait. I got it. Blow jobs three times a day.”

And Faye would laugh through her tears, which only Will could make her do.

“What about baseball?” she’d asked him.

“Just a game, babe. It’s just a game. You and me, we’re the real thing. Right?”

“Right.” She’d put her head back on his big broad chest and ride out the wave of her panic in his arms.

“Breathe, sweetheart,” Will would say, rocking her like a child. “I’m here, and I love you.”

But he wasn’t here anymore.

And he didn’t love her anymore.

If the dead could love, they had a terrible way of showing it.

But breathe she did—in and out—and sure enough, when she raised her head she saw people walking into the gas station, a little boy racing to beat his sister to the door so he could be the one to hold it open for their mother. A robin pecked at a rotting pretzel on the asphalt. A shiny blue Corvette with Georgia plates pulled in for a fill-up. Life. It was still happening. The world hadn’t ended. Not even her little corner of it.

Once she was back in control of her emotions, Faye started her Prius. As always she was taken aback by how quietly the car ran. She really never knew if it was running until it moved. Same with her—she didn’t know she was alive unless she was moving—so she kept moving.

The phone rang again. Hagen calling back, either to keep fighting or to apologize. She ignored the call, and she also ignored the urge to toss the phone out of the car window into Port Royal Sound.

Faye found Federal Street easily, thanks to her tourist’s map. Father Pat Cahill had said he’d be painting the marshlands, but that didn’t narrow things down much. The entire place was surrounded by marshlands. She drove to the very end of the road; if she’d kept driving she’d drive straight into the water. Although tempting—today especially—Faye imagined with her luck the car would land on a dense patch of swamp, and she’d have a few hours to wait before sinking enough to even get her feet wet. Although she couldn’t think of many good reasons to go on living, she also couldn’t think of any good reasons for dying. So she went on as most people did for want of a viable alternative.

Two beautiful old white houses stood proud and dignified on either side of Federal Street, but only one of them had a man sitting on the lawn in front of an easel. The house he painted was a grand antebellum mansion, three stories, white, red roof, green shutters and a porch one could get lost on without a map and a compass. Before leaving the car, Faye checked her face in the mirror looking for any telltale signs of her recent breakdown. The makeup was an easy fix, but she couldn’t do a thing about the redness in her eyes except hope Father Cahill didn’t notice it. She grabbed her camera bag from the backseat. Might as well get some work done while she was here.

She strode across the lawn toward him, and he turned her way and gave her a broad smile.

“Are you my new patron?” he called out. “If so, I thank you and owe you an apology.”

Faye smiled back. “No apologies necessary. The kid let me have it for twenty-five bucks.”

“Twenty-five? Highway robbery.” He rubbed his palms on his paint-smeared khaki slacks, and then held out his hand to her. She was struck by how much he looked like Gregory Peck in the late actor’s last years. Minus the mustache but still with the glasses. His black T-shirt was as paint riddled as his pants. Did he wipe his paintbrushes on his clothes?

“Thanks for meeting with me, Father Cahill.” He had a nice handshake, firm and friendly.

“Pat, please. And I’m retired, so it’s not like I have a full dance card. Pull up the stool and tell me about yourself.” He didn’t say card, he’d said cahd. She knew she was dealing with an old Boston boy. If Kennedy had lived, this was probably how he would have sounded in his seventies.

He passed her his wooden stool and he sat on the stone bench where he’d set up his paints and brushes.

“Not much to tell. I’m in town for a couple months taking pictures for a fund-raising calendar.”

“I know that calendar well. They preservation society ladies are nice enough to buy my paintings every now and then. Their mission in life is to take pity on old relics.”

Faye laughed. “You’re not an old relic.”

“What makes you think I was talking about me?” He winked at her to show he was kidding. “How’d you swing this gig? You’re not a local. Sound like a damn Yankee to me.”

“Friend got me the job. But you’re not a local, either,” Faye said.

“What gave it away?” he asked.

She smiled. “I’m from New Hampshire. You’re not my first Masshole.”

Pat laughed loudly, a good rich laugh.

“Guilty. I was a pastor here in the midsixties. My first church. Fell in love with the islands back then. Always planned to come back, and here I am.”

“Midsixties? You must have been a baby.”

“I was. Big twenty-seven-year-old baby. God help that dumb do-gooder kid. I was not ready for the South during desegregation. Let me tell you this—anyone nostalgic for the past never lived there.”

“Says the man who is painting a two-hundred-year-old plantation house. Thought you were painting the marshes.”

“Marshlands. That’s the name of the house. The owner wasn’t a planter. He was a doctor. The doctor who discovered a treatment for yellow fever. You discover something that can save lives during an epidemic and you get a free pass to own a nice house.”

“Fair enough,” she said. “It is a gorgeous house.” Faye pulled out her camera and examined it through the viewfinder.

“Light’s not very good today,” he said. “Too overcast. I doubt you’ll get a decent shot. At least in painting I can pretend the sun’s there.”

“I’ll come back tomorrow if the sun’s out. I got some beautiful shots of the Bride Island lighthouse yesterday. A friend took me out on his boat.”

“Yes. It’s very nice.” He didn’t sound as enthusiastic as she’d expect from someone who had painted the lighthouse so lovingly. Very nice? That’s all?

“What can you tell me about the lighthouse?”

“Not much. Only what Ms. Shelby told me. She said it was built to protect ships from the sandbar. Third-order Fresnel lens. Seven-second night mark. Solid white day mark. Decommissioned in, oh, ’45, ’46? It’s been rotting there ever since. That’s about it.”

“Ms. Shelby? You know her?”

“I do. Met her at a party, and she and I had a nice talk. I asked if I could paint it, and she said I could go out there anytime I want as long I stayed out of the lighthouse. It’s not structurally sound anymore. That whole corner of the island is very dangerous.”

“What else is out there?”

“Ms. Shelby prefers to keep the land as pristine as possible. There’s not much out there.” He flicked a fly off his canvas. “Trees. A few houses, but those are on the south side of the island. A barn. Handful of horses and horse trails. A few ruins. A few graves. And then there’s the lighthouse and what’s left of the keeper’s cottage, which isn’t anything but the stone foundation.”

“How did a lighthouse get on private property?”

“The government leased the land from the old owners. Four acres, which is a postage stamp on that island. That was back in the 1800s, when lighthouses were popping up along the coast. After they decommissioned the light in the forties, they left it up. Cheaper to let the elements have it than tear it down. Can I ask what your interest is in the lighthouse?”

Before Faye could answer, a small gray tour bus rattled up the driveway to the Marshlands and stopped. Pat gave a dramatic sigh as it unloaded a batch of tourists onto the lawn.

“Now, before we go into the house,” the pretty young tour guide said, shouting over the murmur of elderly tourists, “let’s walk over to the telescope and take a look at the sound.”

“Every single damn day...” Pat sighed. “I should have found a different mansion to paint.”

“Through the telescope,” the tour guide went on, oblivious to Pat’s annoyance, “you can see the sound side of Seaport Island, or what we locals call Bride Island. It’s an unusual island rich with history. If you look up you’ll see the top of a beautiful white lighthouse peeking through the tree line,” the woman said in her sweet-as-pecan-pie accent. “Pretty as it may be, the lighthouse is closed to the public. The water is notoriously choppy at the north seaside of the island, and more than three dozen people have lost their lives in those waters in the past hundred years—”

“Including the Lady of the Light,” Pat recited along with the tour guide, word for word, not missing a single beat. “Faith Morgan, the lighthouse keeper’s beautiful teenaged daughter...”

“You’ve heard this all before?” Faye asked.

“It’s enough to make a man toss a tour guide into the swamp. That’s her in the painting, by the way.”

“The tour guide?”

“No,” he said. “Faith Morgan.”

“The girl on the pier with the bird? That’s her?”

Pat nodded as he capped a paint tube and dropped it into his gear bag.

“Why did you paint her?” Faye asked. “Why not the Bride of Bride Island? Didn’t she drown, too?”

“The subject picks the artist, not the other way around.”

“That’s not very helpful.”

Pat glanced at her before turning his attention back to his painting.

“I didn’t realize you needed my help,” he said.

Faye sensed she was asking Pat questions he didn’t particularly want to answer.

“I’m sorry,” she said. “I know I’m being nosy. I have a reason for asking, I promise.”

“What’s the reason?”

“It’s a stupid reason.”

“Tell me your stupid reason, Faye. You’ve piqued my curiosity.”

“I just... When I saw the painting, I thought she was someone I knew. That’s all.”

He gave her a long searching look.

“Someone you knew. Who?” he asked.

“You’ll laugh.”

“I’d never laugh.”

Faye sighed. She was pretty sure the man would laugh.

“Who did you think the woman in the painting was?” Pat asked, his voice awash with the tender concern that must have served him well in his decades as a priest.

“I thought, maybe... I thought she was me.”