Читать книгу The Night Mark - Tiffany Reisz, Tiffany Reisz - Страница 9

Оглавление3

Ty had the boat, but Faye had the car. Unless she wanted to ride twenty miles on the back of Ty’s scooter, she would be driving herself on her own date. It was nice. She felt very modern. Old but modern.

Ten minutes into the drive to the dock on Saint Helena Island, Faye pulled over in a church parking lot and gave Ty the keys.

“You want me to drive?” he asked, cocking his pierced eyebrow at her.

“I can’t drive and location scout at the same time without getting us in a wreck. I assume you can drive?”

“I have my learner’s permit,” he said, taking the keys.

“You’re cute.”

“The goddamn cutest,” he said as he opened the door and got behind the wheel.

As Ty drove, Faye stared out the window and jotted the occasional note on her steno pad. She should take pics of the old Penn School. The trees surrounding it were some of the most photogenic she’d ever seen. She also noted a crumbling ruin of a church that would make for a beautiful shot, maybe even the cover of the calendar. Thankfully Ty didn’t pester her with small talk as he drove them to the boat. He pointed out interesting scenery here and there—that road took her down to the old fort, this road took her to a converted plantation house... Useful things. Helpful things. She made notes of them all.

They arrived at the dock, and Faye nodded her approval at the boat. It looked adequately seaworthy, some kind of speedy fishing boat converted into a research vessel. It had a blue-and-white hull with the words CCU Marine Science painted on the bow and the number four on the stern.

“You won’t get in trouble for taking me out on your school’s boat, will you?” she asked.

“It’s mine for the summer. As long as I give it back in one piece with a full tank of gas, and I get my work done, they don’t care what I do with it.”

“What are you working on this summer?” Faye asked as Ty took her hand to steady her on the wobbling boat ramp. Inside the boat she sat on the battered white vinyl seat, mindful of the box of instruments on the floor as Ty settled in behind the wheel.

“Beach pollution mostly,” he said, as he steered the boat away from the dock. “The effects of pollution on coastal wildlife, the fish especially. I’m taking water samples all summer up and down the coast.”

“Are these beaches polluted?” she asked. “They look clean to me.”

“Think about rain,” Ty said. “Think about a rainstorm in your town. Water comes down and washes everything clean, right? What sort of stuff gets washed away in a rainstorm?”

“Bird shit,” she said.

“Squirrel shit.”

“Bat shit,” she said, and they both laughed.

“Oil from your car on the street. All that gets washed into the gutter, which goes into the sewer. Where does that sewer go?”

“Please don’t tell me the ocean.”

“Goes right to the ocean. Decades ago they built these drainage pipes from the cities, and those pipes empty into the ocean near the beaches. That’s why you shouldn’t swim around here after a rainstorm. Like swimming in a sewer.”

“That’s disgusting.”

“It is what it is,” he said with a shrug. “People want to pretend all that shit magically disappears into the gutter and is never seen again. But it’s gotta go somewhere, right?” He started the engine and eased the boat toward open water, steering it neatly between two sailboats, one with the elegant name Silver Girl and the other with the less-than-elegant name The Wet Dream.

The boat bounced hard as it skimmed over the top of a large wake left by a fifty-foot yacht. But Ty seemed imperturbable at the helm. He drove with a focused calm, intent without intensity—a true expert. She liked experts. The world needed more people who were good at their jobs.

“So why marine biology?” Faye asked, shouting over the steady hum of the engine.

“Grew up near Myrtle Beach, watched sea turtles hatching when I was a kid and fell in love. That’s all I’m trying to do—keep these beaches for the turtles. Don’t give a shit about the people.”

“That’s not very nice.”

“People are why we’re in this mess. Last year I pulled ten plastic bags, two Coke cans, half a nylon fishnet, and a goddamn pink Croc shoe, size six, out of the stomach of a shark. You know what we say about that down here?”

“What do we say about that down here?”

“That ain’t right. That’s what you say. You try it.”

Faye put on her thickest faux Southern accent. “That ain’t right.”

“Not bad. I took pics of all that mess, made signs and hung them up on every beach from here to Savannah.”

“You must make lots of friends that way.”

Ty snorted a laugh. “Yeah, they aren’t too happy with us when we tell everybody their fun summer vacations are killing the wildlife. They think we’re scaring off tourists. We are, but we’re not doing it to be assholes. We’re doing it to wake people up.”

“Are you waking them up?”

“All we can do is ring the alarm. Most people aren’t going to start paying attention until they have dirty ocean water on their doorstep. Bad as it is, I admit I’m gonna laugh when those rich white boys are playing golf in three feet of seawater.”

“My ex-husband was one of those rich white boys. He loved coming down here to golf with his buddies.”

“Sorry,” he said, looking awkward.

“I’m not.” She winked at him.

Ty smiled and hit the gas. Coming here had been a good idea. She should thank Richard for sending her the job. This job was just what she needed—work. Real work. Meaningful work. Plus sand, surf, seafood and a chance to be her old self again. She knew the old Faye, the Faye who’d existed before the miscarriages and the failed marriage... The old Faye wasn’t sad like the new Faye. The old Faye felt things, felt them deeply. The old Faye fought for things, too, didn’t give up or give in. And the old Faye would definitely go on a date with Ty. Absolutely.

Ty glanced at her out of the corner of his eye. A college boy had just checked her out.

Maybe the old Faye and the new Faye had something in common.

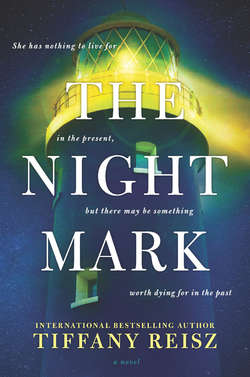

“Is that it?” Faye asked, pointing to the top of a lighthouse peeking out from the tree canopy.

“That’s Hunting Island. Pretty lighthouse. You can climb it for two dollars.”

“I think I can cover that. I’ll go tomorrow. Today I want to see Bride Island’s lighthouse.”

“We’re a couple miles out from there still. The lighthouse is on the north beach. You can see it a lot better than the Hunting Island lighthouse. It was never moved so it’s right on the water.”

“What do you mean it was never moved?” Faye asked, pausing to dig a strand of hair out of her mouth. She’d forgotten how windy it got on a boat.

“You see that long spit of sand there?” Ty pointed to what looked like a yellow cat’s tail lounging a few hundred yards out into the water.

“I see it.”

“That used to be land. And that’s where the Hunting Island lighthouse stood. Built in the 1870s, but they had to move just a few years later. The land had eroded that much already. Going, gone, almost gone...”

“It’s really all going away, isn’t it? The coast?”

“Let’s just say you won’t catch me buying a beach house.”

“It’s too bad. I always feel like a better person when I’m on the water.” The air smelled cleaner here. The water seemed purer. She wanted to strip off her clothes and dive off the side of the boat and let the water baptize her a free woman.

“The ocean is big,” Ty said. “And we aren’t. It’s good to be humbled every now and then.”

“You ever go through a divorce?” she asked.

“Not yet.”

“Trust me, I know from humble.”

“You don’t seem humbled,” Ty said.

“What do I seem like?”

“Like a woman who just got out of jail.”

Faye grinned and was about to ask him what a woman just out of jail ought to do first when Ty raised his arm and pointed.

“There it is,” Ty said, and Faye looked up from the dancing blue water to the island on their port side.

“That’s Bride Island?”

“That’s it.”

Faye studied it, not sure what she was looking for except something to justify the trip out here. From this distance, about five hundred yards from shore according to Ty, it looked like Hunting Island. White sandy beach, a line of ocean debris where the tide met the shore and a thick forest of trees. Faye picked up the binoculars and studied the trees. She saw no palms or palmettos, no pines, no evergreens at all.

“Are those live oaks?”

“I don’t think they’re dead oaks,” Ty said.

“You know what I mean.”

“They’re white oaks. Lady who owns the island owns a bourbon distillery in Kentucky. They get the trees for the bourbon barrels from here.”

“White oak? Interesting. Naturally occurring or did the owner plant them?”

“You know anything about Bride Island?” Ty asked, slowing the boat.

“Not a thing except I couldn’t find it on the guidebook map.”

“It’s just Seaport Island on the maps,” he said. “But call it Bride Island if you want to sound like a local.”

Ty turned off the boat and let it bob gently in the water.

“Where’d the name come from?” Faye asked.

“Some rich planter came over from France in 1820 or something. He sent home for a girl to marry and they shipped her over here, got her in the rowboat to bring her in. They say it was love at first sight. She was so beautiful he waded right into the water to meet her boat. And when she saw him coming for her, she got out of the boat in her fancy dress and eight hundred skirts underneath and waded out to meet him. But the water weighed her down so hard, she started to go under, and he picked her right out of the water and carried his bride to shore. So it’s Bride Island.”

“Romantic,” Faye said. “Minus the almost drowning. Don’t swim in big dresses.”

“Gets more romantic. Their kid fell out of a tree and broke his neck. The bride drowned herself. And the husband went crazy and committed suicide by burning the house down with him inside it. But he was a slave owner so you know what we say to that?”

“That ain’t right?” Faye asked.

“Nope. We say this.” Ty raised his hand and defiantly flipped off the island. Faye smiled. She appreciated the sentiment. “Legend is, if a girl swims naked in those waters, she’ll find her true love right after. But don’t do that. Lotta girls have drowned out here. Only man they meet is Jesus.”

“I’ll make a note not to do that, then.”

“You don’t want to find your true love?” he teased. “Or drown trying?”

“I just got divorced.”

Ty shrugged. “Nobody wants to be alone.”

“I do. I’m never getting married again—that’s for sure.”

“You say that now...”

Faye shook her head, tried not to smile. Had she been this sure of herself at twenty-two? Probably. She wouldn’t tell him he’d be awash with self-doubt by thirty. Maybe he was one of the lucky ones blessed with eternal certainty of purpose. Once she thought she knew it all, too. All Faye knew now was that she knew nothing except what she’d told Ty—she never wanted to be anyone’s wife ever again.

While pretty and picturesque, Faye didn’t see anything on the south shore of the island worth photographing. No houses, no landmarks, no rock formations or wildlife. Only sand and grass and trees. Ty started the boat back up, and they made their way around a bend to the north shore of the island.

And there it was.

Faye stood up and gripped the gunwale, camera momentarily forgotten.

The lighthouse appeared like something from a dream or a painting of a dream. Solid white and shimmering wet after a recent rain, it shone like a pillar of pure moonstone. The roof of the lighthouse was black and glinting and below it the widow’s walk around the lantern room was like an iron choker. The glass panels surrounding the lantern room looked intact, and in the evening sunlight they winked and flashed, casting the illusion that the beacon inside still burned. True, the paint was peeling and the stone facade chipped and cracked, but it was magnificent, dignified and elegant, like an English stage actor who’d played Hamlet in his youth and in his later years strode the boards as Lear. Once a mad prince, now a mad king.

“You like it?” Ty asked.

“I love it,” she breathed.

“It’s not bad,” Ty said. “Only one on the East Coast with a solid white day mark.”

“Day mark?” Faye repeated.

“Lighthouses have a day mark and a night mark. The day mark is what they call the paint job,” Ty said. “Some lighthouses have wild paint jobs. I’ve seen candy stripes and diamond patterns, red stripes and black stripes.”

“And the night mark?”

“The night mark is the pattern the light flashed. Some lighthouses had a steady beam. Some lights flashed. That’s how navigators told lighthouses apart. Every part of a lighthouse had a use. You have electronics and radar and sonar and GPS on boats now. Imagine trying to get from here to Maine without any of that.”

“I couldn’t get from Columbia to Beaufort without my GPS.”

“Yeah, I’d last three days if that before I ran into a sandbar or reef. Lighthouses saved a shit ton of lives.” Ty narrowed his eyes at the lighthouse and shook his head. “Probably won’t last much longer before it falls into the ocean.”

“I’ll make it immortal,” Faye said, pulling her camera out of her bag. She lifted it to her eye and got off a few dozen shots as quickly as she could. Despite sitting on the very edge of the water, the lighthouse looked secure enough to climb if she could find a way to it. It sat on a base of rock four feet or more above the sand. Behind it she saw another line of rock.

“What’s back there?” Faye asked, pointing at the rocks.

“Probably where the keeper’s cottage stood,” Ty said, squinting at the shore. “It was a nice job if you could get it. You get a house and you go to work ten feet from your back door. The beach is your front lawn. Of course, you have to climb about a million stairs a day. And there’s nobody else for miles around if you get hurt or get sick. And when the hurricane hits, you got nowhere to go except inside the lighthouse.”

“That sounds like my dream job,” Faye said. “I’d take pictures of the beach every single day and watch it change through the seasons. And I’d have killer quads climbing those stairs three and four times a day.”

“Sounds boring as shit to me,” Ty said.

“Maybe I was a lighthouse keeper in my past life.”

“Maybe you were boring as shit in your past life.”

“Distinct possibility,” she said, getting off a couple more shots as they rounded the island’s northern shore.

“It’s a shame the lighthouse is locked away on a private island. It should be open to the public.”

“What? You want tourists climbing up and down it every day, putting their gum on the steps and tossing their Coke bottles off the top?”

“Maybe not. But I want to climb it,” Faye said. She didn’t want to climb it. She needed to climb it.

“I’m sure there’s a way. Just not from here. You can’t see it from here, but there’s one nasty sandbar under the water by the pier.”

“It’s okay. I’ll find a way out there. I’ll sweet-talk anyone I need to.”

Near the base of the lighthouse, Faye noticed the remnants of an old pier, thick, rotting wood pillars poking out of the water like a hundred tiny islands. At the last pillar where the pier had once ended, Faye saw a bird land—a white bird with a long bill and a blue-black head.

“Ty? Do you know what that is?” She pointed at the bird. Ty narrowed his eyes. She handed him the binoculars and he peered through them. He laughed.

“Somebody must be having a baby,” he said.

“What is it?”

“A stork. A wood stork.”

“Do you see wood storks around here often?” she asked.

“Never seen one out here. Not too many of them around anywhere.”

“I swear to God that very same bird or its identical twin was perched on my balcony at six o’clock this morning. Bizarre.” She didn’t tell Ty about seeing a bird just like it when she’d scattered Will’s ashes. She liked Ty and didn’t want him thinking she was imagining things like birds stalking her.

“You sure you aren’t pregnant?” Ty asked.

“If I were, I’d still be married.”

“Just checking. I mean, you know how storks are.”

Faye stared across the water at the stork. It turned its large head and seemed to stare back at her.

“I had this baby book once,” Faye said. “Don’t ask me why, doesn’t matter. But it had a whole chapter on the stork symbol. Supposedly in Egyptian mythology, the stork was the symbol of ‘ba’ or the soul. While a person slept, their soul would fly in the form of a stork and come back to him. They could even carry the souls of the dead back to the body. I think. Read it a long time ago.”

“That stork is carrying some dead guy’s soul? I like babies better. Long as it’s not my baby.”

“Can you kill the engine? I don’t want to scare it away.”

Ty cut the engine and peered through the binoculars again. Faye lifted her camera to her eye but took no pictures. She was waiting. She sensed the second her shutter snapped the bird would fly off, and she would lose the shot. She had to get it right the first time.

The boat bobbed in the water, drifting ever closer to the pier. The shot lined up the way she wanted—the lighthouse filled the background, the pillar and the stork were left of center and the trees formed a frame on either side.

One...two...three...

Faye clicked the shutter and got off as many shots as she could in quick succession. Her instincts had been right. As soon as the clicking reverberated over the water, the bird took off. Faye couldn’t have planned it better. The wood stork soared into the sky, heading straight toward the sun fearless as Icarus, and she captured every last beat of its wings.

“Perfect,” she said, flipping the camera over. She scrolled through the pictures, creating a sort of flipbook as the bird tensed, stretched its wings and then launched itself into the sky. She scrolled backward and set the stork back down onto the pier like magic.

“Damn,” Ty said, glancing over Faye’s shoulder. “You’re good.” His shoulder butted against hers, and he seemed genuinely impressed by her work.

“I’m not bad.”

“You make much money doing this?” he asked.

“I didn’t become a photographer for the money. Nobody does, I promise.”

“Why’d you do it, then?”

“When I was younger, I thought I wanted to be a photojournalist. A modern Dorothea Lange.”

“Who?”

“You’ve seen her pictures. She took photographs of migrant workers during the Great Depression. People in bread lines, starving people, people driving across the country to get jobs picking fruit in California. When those pictures were published, it woke the country up. FDR’s New Deal might not have happened without her pictures. Before her the poor were seen as defective, as inferior. She took beautiful pictures of poor people, dignified pictures. People saw themselves in the suffering. They saw the humanity. One photographer, one woman, in the right place and the right time could change the world.”

“You gonna change the world?”

“That was the plan. Once upon a time. But every college kid thinks they can save the world.” She grinned at him, and he rolled his eyes. “But it’s a hard gig to get into, the changing-the-world gig. I settled for working at a tiny newspaper in Rhode Island out of college. Newspaper jobs are nearly impossible to get now. Good thing my ex-husband had money or I might have starved. Or worse, had to get a real job.”

She joked about it, but the truth was, she regretted letting Hagen’s money keep her at home when what she should have done was go back to work doing what she loved. But when they’d gotten married she’d been in no shape to save the world. She could barely get out of bed the morning of their wedding. So what was stopping her now?

“Dorothea Lange took pictures of people suffering from the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl, and now the Social Security Administration and Medicaid exist. I take pictures of lighthouses for desk calendars. So much for saving the world.”

“Hey,” Ty said, “your pictures could save that lighthouse. It’s a piece of history. That light saved lives, and you can return the favor. People see that lighthouse and they start to care about it. Out of sight, out of mind, right? So isn’t the reverse in sight, in mind? Maybe if somebody like you took pictures of these islands a hundred years ago, they wouldn’t be in the shape they are now. And even when that lighthouse is gone, when all the islands are gone, we’ll have your pictures. Better than nothing.”

“Right. Better than nothing.”

Faye smiled and looked at her pictures again. She couldn’t believe her luck. A dozen gorgeous shots, any one of them could grace the cover of the calendar. A home run on her first at bat. That never happened.

Ty started the boat’s engine up again. With a relaxed, practiced air, he steered them around the ruins of the pier and back into open water.

“Where to now?” Faye asked, slipping her camera back into her bag.

“Dinner. Oysters if you can handle it.”

“I can handle oysters. You buying?” she teased. She’d never make a college kid buy her dinner.

“How about this? I’ll give you the oysters in exchange for the clam.”

Faye stared at him. “That is the grossest thing anyone has ever said to me. I’m almost impressed. No, I am impressed. Good job.” She slapped him on the back.

“Thank you, baby. I’ll be here all week.”

Faye was too amused and too happy to be offended. Not that Ty could offend her if he tried. After four years in a bad marriage, one dirty pussy joke couldn’t begin to ding her armor. Oh, but that smile of Ty’s, that sweet, sexy smile could. It wriggled its way through the chinks in her chain mail.

Tonight she was going to make very bad decisions.

The rest of the evening passed in a blur. Faye and Ty both had a little to drink at dinner and then a lot to drink back at the Church Street house. So it wasn’t that much of a rude awakening to find Ty still in her bed when she woke up around 3:00 a.m.

He lay on his stomach, facing away from her, looking so painfully young and terribly sweet. She forced down any guilt she might have felt. This hadn’t been his first time, and it wouldn’t be his last. Might not even be his last time tonight. She’d almost told him during their first round that it was the best sex she’d had since getting married, but she kept that comment to herself. After all, Hagen had set a low bar.

Faye slipped out of bed, put on her bathrobe and went to the bathroom. Ty stirred as she slid back in next to him.

“Just me,” she whispered as Ty rolled over to face her.

“Did I fall asleep? Sorry. Your bed is bigger than mine.”

“I don’t mind. Just be careful sneaking out. I don’t want to get in trouble with Miss Lizzie. She seems a little on the religious side.”

“She makes Mother Teresa look like Miley Cyrus.” Ty slid from bed and started gathering his clothes. She rolled over onto her side to watch him dress in the dark. “Luckily she sleeps so hard we could knock the headboard through the wall and she wouldn’t wake up.”

“That sounds like the voice of experience.”

“Did you think I was a virgin?” he asked, crawling over the bed to her.

“No, but I was.”

He laughed softly and kissed her. “Hope you had fun,” he said.

“I did.”

“You sure?” he asked. Faye blushed in the dark. She hadn’t been able to come during the sex. She’d tried, but it was going to take a while before she figured how to use her body for anything other than baby making again. But Ty didn’t need to hear that.

“I did have fun,” she said. “Don’t take my lack of orgasms personally. I’m a little out of practice.”

One more kiss and one more smile. “Practice makes perfect.”

On his way out of her room she stopped him with a whispered question.

“Hey,” she said. “What’s the name of the island with the lighthouse again? Not Bride Island, the real name? Sea Island?”

“Seaport Island.”

“Thanks. I need it for the caption.”

“I’ll take you out there again anytime you want.”

“I might take you up on that. How much will you charge me for it?” she asked, smiling.

“One clam.”

Ty crept into the hallway and was gone, leaving Faye laughing in bed. She didn’t hear a single footstep creaking on the hardwood.

Faye tried to go back to sleep, but it eluded her. Her new life had officially begun with a bang and a whimper or two. Sliding out from under the covers, she walked naked to her camera bag sitting on the floor. She enjoyed the breezy tickle of the night air on her breasts as it wafted in under the blinds. It made her tingle in a pleasant way.

She hadn’t had a chance to upload today’s pictures yet and wanted to see the lighthouse again. She plugged her camera into her computer. Ah, there they were, her beautiful photos. The stork, the trees, the glimmering ivory lighthouse. Faye would get this photo printed out and she’d hang it in her room. It was possibly the best work she’d ever done. Maybe she’d finally found her subject. Man Ray had his nudes. Dorothea Lange had her migrant workers. Ansel Adams had his landscapes. Maybe Faye Barlow would have her lighthouses.

She typed “Seaport Island Lighthouse” into the spreadsheet she kept to label her photographs. Out of curiosity she entered that phrase into Google image search to see who else had been taking pictures of the lighthouse. She found a few amateur pictures of the island, most of them obvious iPhone pictures posted on Pinterest. As she scrolled through the results she found a few historical pictures. One of the iron skeleton of the lighthouse as it was being built in 1884. Another when it was completed.

Faye was about to shut her computer down when a tiny thumbprint photograph caught her eye. It was a faded and sepia-toned picture of one of the lighthouse’s keepers who’d been stationed there after World War I, according to the caption.

Faye narrowed her eyes at the photograph. Her heart raced. She clicked on the link and enlarged the picture until the face of the lighthouse keeper filled up the fifteen-inch screen.

“No way...” she breathed, putting the laptop onto the sewing table and leaning in closer, staring at the photograph until her eyes watered. And she stared at it even longer until the watering turned to tears.

Faye reached out to touch the photograph on her screen.

She knew the face in the photograph, knew it well.

It was the face of the only man she’d ever loved.

Will’s face.