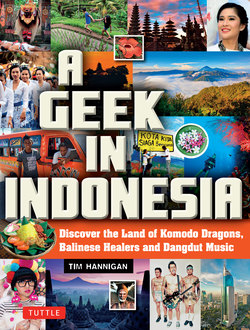

Читать книгу A Geek in Indonesia - Tim Hannigan - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеAn Archipelago of Superlatives

So let’s start with the superlatives… Indonesia is the world’s fourth most populous country, and its biggest Muslim-majority state. It has more than one hundred active volcanoes and something like 17,000 islands, making it the biggest archipelagic nation and the most volcanic place on the planet. It is home to more than a quarter of a billion people, but most of them live on Java which is about the same size as Illinois and is therefore, somewhat predictably, the most densely populated island on earth. The distance between Indonesia’s westernmost and easternmost extremities is about the same as that between London and Tehran. Indonesia is also Southeast Asia’s biggest economy, and the world’s third largest democracy.

And that’s usually about as far as anyone gets. It’s almost as if Indonesia is just too big to make sense of; the safest option has long been to ignore it. For many years, when I mentioned Indonesia to people—be they Brits, Americans, or Indians—all too often they’d respond as if I was talking about a miniscule banana republic. Either that, or they’d enthuse about Bali, as if that was all there was to Indonesia. And on the rare occasions when Indonesia made it into the international headlines, the news was almost always bad.

But in the last few years things have started to change. First up, in 2013 the influential economist Jim O’Neill decided that Indonesia was a “MINT”, one of the emerging nations likely to be the economic superpowers of the 21st century (along with Mexico, Nigeria, and Turkey, plus an earlier acronym-making quartet, the BRICs of Brazil, Russia, India, and China). Stock newsreel footage started showing gleaming Jakarta skyscrapers instead of smoking volcanoes, and alongside stories of astronomical economic potential came tales of mind-boggling social media usage. An edgy Indonesian novelist got flavor-of-the-month status with New York literati; a Welsh film director made Indonesian martial arts the coolest thing on the planet for violence-loving movie geeks; and Internet news feeds started pointing out that the country’s president was a hard-rocking Metallica fan. Oh, and Agnes Monica, Indonesia’s favorite child star turned pop princess, recorded a single with Timbaland. Seriously. There was still plenty of bad news about natural and manmade disasters, but it suddenly seemed that the people affected were as likely to be urban hipsters as rice farmers.

Macet—the Indonesian word for gridlock—is an unavoidable fact of life in the nation’s cities.

The becak is the Indonesian incarnation of the pedicab.

The tourist brochure version of Indonesia does still exist, in the rice terraces of Bali and in plenty of other places besides!

But if it’s no longer possible to totally ignore Indonesia, it can still be very difficult to make sense of it. Tourist guidebooks still paint it as a place of temples, rice terraces, and timeless tradition, in wild contrast to the journalists poring over the latest growth figures, or bemoaning environmental catastrophes. The country’s status as one of the most successful democracies in Asia doesn’t sit easily with bad memories of violence and political turmoil, and the idea that it’s “the world’s biggest Muslim country” can be very confusing when you take into account lurid stories of celebrity scandals. And Agnes Monica’s Timbaland collaboration is about a million miles away from the plaintive tones of a gamelan orchestra.

In places like Kupang, West Timor, public transport comes with a punky style and a bass-heavy sound system blaring the latest hits.

One of the unifying elements of Indonesia is a passion for flavorful street food, on offer in lively night markets and roadside stalls.

Modern Jakarta—known by many foreigners but few locals as “the Big Durian”—is one of Asia’s biggest and most frenetic cities, a place with a constant construction boom and similarly constant traffic problems.

Part kitsch, part cool—a classic Indonesian combination—finds colorful expression in these vintage bikes for hire in Jakarta’s Fatahillah Square, complete with pink colonial pith helmet.

This book is an introduction to what Indonesia has on offer for travelers—its beaches, its mountains, its traditions. But it’s also about the space between the hard news stories and the soft guidebook images where millions of Indonesians lead their lives, a paradise for foodies, surfers, and punks, and a country with 700 indigenous languages and 30 million Twitter users. With any luck it might just convince you that Indonesia deserves to add another superlative to its already impressive roster: the coolest country on the planet…

Hello Mister!—My Personal Journey

Photo! Photo! Village kids in Sumatra jostle for center-stage whenever a foreigner happens to pass by with a camera.

I must have been about seven years old when we did the project about Indonesia at school. Why the teacher thought that a tropical country 7,000 miles (11,300 kilometers) away might be of relevance to a bunch of kids from a little mining village on the brink of the North Atlantic, I’ll never know, but I do remember learning about buffaloes pulling ploughs in paddy fields. I went home, dug a trench in the yard, filled it with water, and threw in a handful of my mum’s pudding rice. It didn’t grow. And neither, to be honest, did the idea of Indonesia.

But fast-forward to the middle of my second decade, and Indonesia was looming large in my imagination. Like many teenagers from Cornwall, I was a fanatical surfer, and on chilly onshore days I’d lie on my bed poring over the cobalt-blue pages of surf magazines. I’d still have struggled to pinpoint Indonesia on the map, but I knew the names of its fabled surf breaks by heart—Uluwatu, Padang-Padang, G-Land, Desert Point.

A few years later, and my peers who had spent summers saving their pennies working on farms or in restaurant kitchens started disappearing eastwards for months each winter. Indonesia, they said, was the cheapest place on the planet to score good waves in warm water. They generally didn’t bring home any souvenirs, but one friend, Stefan, did buy something in Indonesia. It was a cassette tape. We had a shared love of American punk rock, and he handed it to me saying, “It sounds a bit like NOFX.” It was the second album from the Balinese punk band Superman is Dead, and Stefan was right: they did sound a bit like NOFX.

By the time I’d saved enough of my own pennies to head for Indonesia myself—winging my way to Bali through the monsoon thunderheads in the immediate aftermath of the 2002 Bali Bomb—I had a peculiar image of the place. I was expecting to find surf, paddy fields, and punk rock. I found all of them, and a lot more besides.

The wide blue yonder: exploring a remote corner of Indonesia by motorbike and backpack.

I’ve been in and out of Indonesia for a decade and a half now, sometimes wandering the outer reaches of the archipelago as a backpacker; sometimes living and working for extended periods closer to the heart of the country as an English teacher and a journalist, and I’ve still got a geeky enthusiasm for all things Indonesian. There’s a past and a present that are equally colorful. There’s a music scene that might just be the most multifaceted in the universe. There’s food that’ll have you scurrying for second helpings (or, occasionally, recoiling in terror!). There are mountains to climb, football hooligans to dodge, urban chic to admire, and always a new journey to be plotted—these days usually with a whole legion of hip local travel bloggers to give you inspiration.

But the single best thing about Indonesia is just how much Indonesian people like to talk. It’s always dangerous to make sweeping generalizations about any country, let alone one this big, but I can safely say that talking is one thing that unites Indonesians—whether they’re smartphone-toting mallrats in Jakarta, or villagers in the wilds of Nusa Tenggara. Wherever I’m wandering, when locals lounging in some roadside warung shout “Hello mister!”—the standard greeting for a passing foreigner—if I pause to chat, once they’ve stopped laughing at the concept of a bule (“whitey”) speaking Indonesian with a (sort of) East Java accent, I’ll often find myself still there two hours later, still shooting the breeze. And when the topic is Indonesia itself, there’s always plenty to talk about…