Читать книгу Wines of the New South Africa - Tim James - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

WINE AND THE NEW SOUTH AFRICA

In 1994, in a hopeful time as a new democracy came to the land of apartheid, South African wine ventured out into the world—a world of which it was terribly ignorant, and which, in turn, had largely forgotten about it during years of boycott. Perhaps, though, an atavistic memory clung from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when wines from Constantia were welcomed among the world’s greatest. Now, a figure shrunken from long years of isolation, South African wine blinked in the light, a little tentative but with more confidence than was justified—as was to be demonstrated, when the international wine market made it clear that it was going to demand more than just the reflected glow of Nelson Mandela in the background.

Marketers and makers of Cape wine saw and tasted what was selling in London, Amsterdam, and New York, and the alert among them might have realized a problem. But many were slow, reluctant, or complacently ignorant of any problems, while international wine-lovers, still curious and generous about the “new” South Africa, were being indulgent. One moment that can be seen as symbolic, as well as having had an actual salutary effect, came in 1995 when South Africa was trounced in a comprehensive wine competition against Australia, held in Cape Town with judges from both countries. Producers were shaken, many disbelieving: something was undoubtedly wrong, but surely not their wines!

Various industry bodies seem to have then put pressure on SAA, the national airline that had supported the competition, to abandon its three-year sponsorship. Another international competition that had been planned—against Argentina and Chile—never took place. Winemaker André van Rensburg (whose Stellenzicht Syrah had beaten the famous Grange in the match against Australia) reacted trenchantly to this sulky refusal to face reality: “If a winemaker is scared of competing against Chile, he should stop making wine and grow vegetables. The objections of the better-known estates are based on their unjust reputations earned from wine writers who have been too kind to them.”

Fortunately for South African wine, the estates continued to farm grapes rather than turn to broccoli and carrots. Meanwhile, the most important competitions took place when the buyers for supermarkets, national monopolies, and wine shops around the world made their choices. Too many Cape wines were, for example, clearly made from stressed fruit off virused vineyards where the grapes struggled to ripen; too many were overacidified, in accordance with the abstract dictates of the local university enology department, which encouraged safety above all; oaking was not always carried out in a sophisticated manner—and there was some suspicion that the barrels themselves were not always of the highest quality. Furthermore, tastes had changed in the larger world of wine, in ways many in South Africa were only coming to realize.

The local wine industry seized upon the few years of indulgence it was granted; lessons were learned, and the pace of transformation was astonishing. Some changes could come quickly—in the cellar, especially, and some aspects of vineyard management. Other changes—such as finding the land best suited to particular varieties, improved viticultural practices, and working with better and cleaner plant material—would take longer. Those longer-term changes, whose effects would be observed only ten years later, were to constitute something like a second stage in the South African winemaking revolution. But all these effects were part of a more fundamental shift in quality, particularly at the most ambitious end of Cape winemaking.

Other than the swift adaptation to what the world demanded of a modern wine producer, something else was astonishing. In one way, it was precisely the opposite of adaptation, although it did not rest on complacency. Within the arrogant response of producers to their humiliation in the test match against Australia had been a few grains of truth that might become useful and valuable if properly understood and used. It was not certain that the ripe fruitiness that had made Australian wine the darling of the vital British market in particular was entirely something to aim for at all costs. More important was to recognize and assert an independent tradition and some older-fashioned virtues that should not be too hastily discarded. The Cape had nearly 350 years of winemaking behind it. In some of the urging to modernize in order to compete effectively on the international market a demand could also be heard to abandon tradition and the claims of a specific winegrowing landscape in favor of the blandness of internationalist winemaking competence and globalized fashion.

Even in the recent decades, when South Africa’s isolation had undoubtedly led to provincialism, a (small) number of fine wines had not quite fitted what seemed to be demanded by those for whom the new-world standards were provided by Australia and California. Those were the days of Australian ascendancy in the United Kingdom, South Africa’s largest market. Forward fruit and a touch of sweetness seemed to beguile everyone there, from the supermarket customer to the lofty critic. The makers of some apparently old-fashioned Cape wines had endured sniffs and sneers, but they resisted stylistic demands while striving to improve the quality of what they were creating. There was a vague but not unjustified idea abroad, which encouraged them, that South Africa’s natural position in the world of wine was somewhere between the respective styles associated with the New World and the Old. But if ripeness was all for some enthusiasts of modern winemaking, the old-fashioned were not always right, either. There were winemakers for whom defense of tradition was associated with hard, overacidified reds kept too long in barrels of dubious quality, insipidly flabby or too-acidic whites, or ultrasweet fortified wines.

In the introduction to the 1995 edition of his annual South African Wine Guide, when the revolution in local wine was scarcely under way, John Platter described what was happening in tones different from those of his introduction of the previous year, when recession and poor-quality exports had edged his words with despair. He wrote percipiently in his necessarily enlarged Guide:

The stampede of new wines—nearly 400 this season alone—is neither a completely chaotic second-coming, nor a chase into the unknown. South Africa has had a foot in both the Old and New worlds of wine. In reclaiming the past—and past overseas markets—the re-launch of the Cape was always going to be steadied by its long traditions, its ease with wine. The old profile of Cape wine would be swiveled a bit on its plinth, to catch different beams of light, to offer new outlines. But the soils and climates and many of the ways of the Cape remain inimitable and impose a continuity too.

Platter might not even have apprehended the extent of the change that was just starting, but he was perceptive in his conclusion: “Often, the Cape’s youngest wines are its best. And the finest have not yet been bottled.”

In one of the most important developments of all, many in a remarkable younger generation of winemakers (sadly, only a few viticulturists as yet) traveled the wine lands of the world, not just to learn new-world cellaring techniques, but also to taste and marvel at and seek to understand the classic wines of Europe. They brought home reminders of the great fundamental that the finest wine is true to its origins, the soil and climate in which grapevines are nurtured. There was undoubtedly a qualitative leap in Cape wine in the late 1990s, but another, more profound change—precisely, the emergence of increasing numbers of authentic wines—seems to have happened in the first decade of the twenty-first century. In fact, that is why a number of the wineries profiled in this book are so young. John Platter’s point in 1994 remains perhaps more clearly true now: a significant proportion of the best South African wines today were not being made in 2000, and many of what are now recognized as the finest wineries were not yet established.

It is worth stressing the point: the reentry of South Africa into the world since the early 1990s has meant a growth in international sophistication for its wine. At its best, that has meant not the imposition of a bland “international style,” but the emergence of the local story, better told.

Here is an example that works as an argument for this claim, and for the previous one about the more recent deepening of transformation in South African wine, as well as for an illustration of the rich dialectic between local and international in that reinvigorated transformation. For many observers, the class of South African wine that today comes closest to excellence is that of blended whites. In fact, one should say two classes, for two distinct styles are emerging. In the cooler areas, many blends are based on the Bordeaux-blessed marriage of Sauvignon Blanc and Sémillon, taking the classics of Graves as their model. This style was inaugurated here with a Vergelegen wine as recently as 2001, the second style a year later with Sadie Family Palladius. Their successors—and competitors—are now numerous. The second style emerged under the wide, warm skies of the Swartland and has at its core the old-vine Chenin Blanc of the region, with a diverse range of partners. (There’s more Chenin in the Cape than in its Loire homeland, but it was long despised, or at best tolerated for its willing service.)

Of course, such wines are a tiny proportion of South African production and a tiny part of the rebirth of the country’s wine industry, however appealing they may be as signs of achievement and possibility. For the larger picture, statistics of change can serve well (a synoptic table listing many of them appears in the appendix). The most remarkable index of international acceptance is the increase in wine exports over the period from 1993 to 2011, from nearly twenty-five million liters to well over four hundred million. In 2011, exports, having fallen a little over the previous few years in the adverse international financial climate, amounted to 43 percent of total wine production. (It was 6.2 percent in 1993!) That was perhaps just as well, considering that domestic per-capita consumption of South African wine is low and declining, at just seven liters annually. Getting the domestic black population to drink wine at all levels is a challenge the wine industry wants to meet—although it is being a trifle lackadaisical about it. Beer, including traditional African beer, has more than 60 percent of the market share of alcoholic beverages based on alcohol content; wine has little more than 15 percent, somewhat less than spirits.

The most significant political context of the rebirth of South African wine has been the reentry into the world market. (Repercussions of socioeconomic relations within the industry are discussed later in this chapter.) But an important enabling feature has been the unshackling of Cape wine from certain restrictions, which coincided precisely with a situation in which the industry could benefit from greater freedom. Chapter 2 will discuss the effect, through much of the twentieth century, of the all-powerful KWV, which began its life as a national producer cooperative, the Koöperatieve Wijnbouwers Vereniging, but rapidly acquired substantial statutory powers in managing the industry. In the context of the continuing deregulation of other parts of agriculture, which had already taken place before 1994, and faced with further governmental policy changes, the KWV from the early 1990s started to reconstruct itself as a more conventionally commercial force without national administrative duties or powers. For an organization like this, which had been so cozily intertwined with the apartheid government, the prospect of an African National Congress government was not encouraging.

When the KWV applied for permission to convert its legal status from a cooperative to a company, the government opposed the court application until the KWV agreed to make available, in a trust set up for various wine industry purposes, some 477 million rand (the notional value of the benefits to the KWV of its statutory functions). By the time permission was granted, in 1997, the KWV’s abandonment of two of the most important parts of its rule had started having a major effect on the industry: the “quota system,” which, in the name of preventing overproduction, had disallowed expansion into promising new winegrowing areas; and the guaranteed minimum price for wine, which had been part of a system that effectively encouraged production for quantity rather than quality.

It must be said that the KWV left behind it a system that manages well the bureaucratic needs of the wine industry, where control is unquestionably in the public interest. The appellation system that was introduced in the early 1970s, and its associated certification process, work efficiently under the Wine and Spirit Board, the control function contracted since 1999 to SAWIS (South African Wine Industry Information and Systems). Some of the funds wrested from the KWV went to research and generic promotion, and these are also generally well handled. And the industry flourished in the new regime of regulatory freedom, despite the lack of a continuing body to represent and strategically manage the industry. The South African Wine and Brandy Company was formed in 2002 to implement a strategic outline called Vision 2020. It lasted, without apparently achieving much, until 2006. Out of its “restructuring” emerged the South African Wine Industry Council, which was intended to deal with major wine-industry issues, from socioeconomic transformation to streamlining relations among the industry, government, and other relevant stakeholders. It, too, lasted only a few years before being abandoned. There is, at present, no pretense that any body is guiding, or even representing, the industry at the highest level.

THE WINE PRODUCERS

There’s a lot more South African wine about these days than there was in 1993—approximately half as much again. Total production (along with total vineyard area) has only increased by not much more than 20 percent, but now less of what the vineyards yield is doomed to distillation or diversion to unfermented grape juice. The 2011 vintage produced a record 831 million liters of wine, which was about 80 percent of the total wine-grape crop—the remainder going for brandy, distillation, or juice.

More important is the basic quality, and one useful indication of improvement here is the amount that is certified. In South Africa, no wine may carry any information on its label about vintage, origin, or grape variety unless it has undergone a rigorous process of certification. This involves a good deal of record-keeping and paperwork, as all stages of production are monitored to see that the basic sums add up: if so many tons of Cabernet grapes were produced on a particular farm in a particular year, producing so many liters, the authorities will get very anxious if a different volume is bottled. For a wine to be certified it must also meet a minimum level of quality, as adjudged by official tasting panels. In 1993, just 12 percent of wine was thus certified, but the proportion rose steadily each year to about 57 percent in 2011—showing a major increase in ambition.

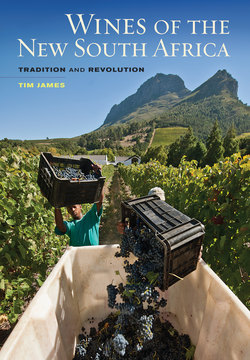

The classic tourist image of the South African wine farm is of the whitewashed homestead and sturdy outbuildings sheltered by oaks at the foot of purple mountains, with grape pickers bearing (no doubt cheerfully) their boxes of golden or purple fruit to the crusher. But as the tourists (also hopefully cheerful) make their harvesttime way around the wine lands, they will inevitably have to wait occasionally behind slow-moving trucks piled high with grapes, and might see them turn down a side road toward what looks like a small oil refinery or industrial plant. With any luck the trucks will not have to stand too long in line there, with the sun beating down on their fragile freight, awaiting their turn to deliver the crop to the crusher. By far the larger proportion of wine, both certified and uncertified (destined for the distillery), is made at such places—unromantic, perhaps, but immensely impressive, with their miles of coiling or rigid pipes, dials and switches, hardworking attendants, and rows of gleaming and enormous stainless steel tanks, some containing a million liters of wine.

Most of these are the country’s cooperative wineries and the wineries that used to be cooperatives before converting to companies. There are still fifty-two of these “producer cellars,” as they are officially known collectively. More and more cooperatives have been commercialized since the early 1990s, largely because of the demand for higher-quality wines. Older arrangements of paying for members’ produce, with acceptance of everything guaranteed, are not feasible in today’s tougher and more exacting market. The KWV is no longer there to take, in its turn, anything unsalable by the cooperative—the national minimum price arrangement, which guaranteed an income, was finally abandoned in 1995. Now the former co-ops are generally owned, as companies, by the farmers who supply them with grapes; the latter’s income, however, now depends much more than before on such matters as grape variety and quality of fruit delivered to the crusher, because there is no longer an obligation to accept substandard or unmarketable material.

The producer cellars crush more than three-quarters of the entire wine-grape harvest—in 2011, 82 percent of the white grapes (some of which are grown specifically for brandy) and 72 percent of the red. Many of them have raised their game significantly, with increased attention to viticulture as well as to what happens in the cellar. A few of them now market single-vineyard and other prestige bottlings—more as a way of encouraging farmers to aim for quality and to build the general reputation of the winery, perhaps, than to maximize income. Generally they bottle and sell under their own label an increasing but still fairly small proportion of their own wine; the larger part is sold off to supplement the needs of private cellars or (most of it) in bulk to the wholesalers and exporters.

The wholesalers and specialist exporters—now including giants like Distell and the KWV—have a long and important history in South African wine. Before the rise of the private estates and of direct sales by the cooperatives, it was the wholesalers who were responsible for the overwhelming proportion of wines on the market, while the KWV had a virtual monopoly on exports. Wholesalers continue to market South Africa’s biggest brands locally and internationally, though they no longer have things all their own way. There are also far more of them around than there were in the ultracentralized days before the revolution of the 1990s. There were fewer than half a dozen bulk buyers in the early 1990s; now there are more than a hundred, many of which buy wines solely for export under labels that South African wine-lovers would not recognize.

Many such merchants are fairly small, of course, and none is anywhere near as large as Distell, which accounts for up to a third of all South Africa’s still and sparkling wine production. Distell was the result of a merger in 2000 of Stellenbosch Farmers’ Winery and Distillers Corporation. They had, in fact, been united for some years as Cape Wines and Distillers until 1988, when government decreed their separation; in 2000 there was no opposition from the Competition Board to the merger. And in fact the improvement in some of the well-known brands offered by Distell has paralleled the country’s general improvement, with labels like Nederburg and Fleur du Cap offering excellent quality at different levels. Distell does own some vineyards and crushes some of its own and bought-in grapes, as well as having some joint ventures with important estates; but the great majority of its wine, especially of what it produces for the middle and lower parts of the market, comes from the producing cellars. The wholesalers that crush at least some of their own grapes account for about 7 percent of the total harvest each year.

While the larger producers have increased their penetration of the fine wine market, the sort of wine that is the main concern of this book, which approaches the level of artisanal rather than industrial, comes mostly from the cellars of private producers. Their share of the total crush rose to 17 percent in 2011, but their numbers have grown even more substantially than their share of the crush, from 170 in 1993 to more than 500 by 2011. This is a total that will still seem surprisingly small, however, to someone who knows that the young wine industry of Washington state, for example, has many more wineries than this, despite a much smaller area under vine. The discrepancy is explained partly by the average price reached per bottle of wine and partly by the presence of many more wealthy people in and near Washington to buy the wine and—at a different level of wealth perhaps—to invest in wineries. It seems inevitable that the number of “lifestyle” farmers in the United States would be much greater than here—though certainly some of the new wineries and estates in the Cape have been established by wealthy outsiders willing to do what one of them, banker G.T. Ferreira of Tokara, self-deprecatingly described as seeking “return on ego” rather than “return on investment.”

Furthermore, of course, the cooperative tradition in South Africa is a drag on the number of grape-crushing facilities. Although the number of grape farmers has declined in recent years, largely because of consolidation in tough economic times, there are more than 3,500 of them—many more than in Washington state. A minuscule proportion of these grape farmers has either converted entirely to producing their own wine or has started diverting some of their grapes—sometimes from their best vineyard blocks, separately farmed for quality rather than quantity—into bottles under their own labels. That would account for some of the rise in the number of private wineries. Many of these producers are small, though few are as tiny as Bein, which makes good Merlot off its 2 hectares of vines; and they range up from there. Koopmanskloof (in Stellenbosch, like Bein) has 520 hectares, while Willie Dreyer harvests more than 1,100 hectares of vines on his four farms in the Swartland and Voor-Paardeberg, most of the grapes going elsewhere for vinification.

THE CHANGING VINEYARD

A more important contribution to the development of South African wine since 1994 than grape farmers being tempted into making wine for their own labels has been the appearance of entirely new wineries. Many of them have planted vines on virgin land—occasionally in the traditional wine lands, but more in new areas that have opened up since the early 1990s. To taste the Berrio Sauvignon Blanc, grown amid the salty bluster of Agulhas, or a Crystallum Pinot Noir from Hemel-en-Aarde, and realize that they were simply not permissible before 1992 adds a bizarre note to the pleasure. That was the year that the KWV abandoned the quota system, freeing would-be winegrowers to spend their money as foolishly as they wished, driven by ambition to make fine wine.

This expansion has been one of the most exciting aspects of the history of South African wine in recent times. There has even been growth as far distant from Stellenbosch as the subtropical province of KwaZulu-Natal. But new vineyards have also usefully extended the range of such well-established areas as Constantia and Stellenbosch. On the other hand, much of the significant change to the vine landscape has come about, first, through better viticultural practices, and second, through replanting. Sometimes the same vineyard has been replanted with a more suitable variety or better combination of variety and rootstock; sometimes an estate has abandoned the vineyards in the rich alluvial soils of a warm valley floor and dragged the vines, as it were, up the lower slopes of the mountains to cooler sites where lower yields will come from the poorer soils. Virgil knew that vines love hillsides (Bacchus amat colles), and would have nodded approval of the changing view from a good vantage point in Franschhoek, Stellenbosch, or Constantia—seeing those high verdant patches.

Because of the dramatic changes to South African wine, one might have expected more absolute growth than has in fact happened. Australia and Chile, for example, have enormous new plantings, while the net growth in the total wine-grape vineyard area of South Africa in the fifteen years since 1996 (from 95,721 to 100,568 hectares) has been minimal. Much of that 5,000 hectares is accounted for by vineyards intended for high-quality wine in the recently opened cooler areas. In terms of the total production of wine, South Africa ranks eighth in the world, recently overtaken by Chile. In the early 1990s South Africa’s vineyard area and wine production were far ahead of Australia’s (and, even more, Chile’s). But Australia’s international success was accompanied by great expansion of vineyard area and production: the latter rose by something like two-thirds in the decade and a half to 2011 (something now regretted by many, of course). Chile’s production much more than doubled in the same period. Such spectacular growth did not happen in South Africa, for various reasons: a less overwhelming international success, less interest in investment by local or foreign forces, but also, significantly, the lack of irrigation potential, which means that South Africa is close to its limit of irrigable vineyard.

Faltering exports in a time of world economic sluggishness, together with depressed local demand, have even led recently to a reduction in the total vineyard hectarage. Since 2003 the number of hectares newly planted has been declining, and since 2006 it has been exceeded by the hectares uprooted or abandoned. The troubling aspect of this trend is its implication that vineyards are not being renewed as often as is generally thought desirable for the health of the industry: while carefully maintained older vines are frequently good news for high-quality production, an aging vineyard is not conducive to economically viable higher-yield production. Furthermore, there is every likelihood that in hard times for farmers, more and more vineyards are not being cared for as assiduously as they should be.

The expansion that has occurred over the past decades has brought continuous development of the pattern of official appellations. South Africa’s Wine of Origin (WO) system, which covers origin in terms of vintage and cultivar as well as appellation, is the most established and elaborated of any wine-producing country outside Europe. It was initially promulgated into law in 1973 (details of its workings are given in chapter 4). Although the WO system does not stipulate such things as viticultural and cellar practices, it is becoming increasingly refined, through subdivision of larger appellations into smaller ones, based on identity of terroir (soil and mesoclimate particularly). This in turn is both an expression of and encouragement for a degree of specialization—at least marking an emerging association between particular areas and grape varieties or styles of wine: Elgin, Constantia, and Elim for Sauvignon Blanc, for example; Hemel-en-Aarde for Pinot Noir and Chardonnay; Stellenbosch for Cabernet Sauvignon; and the Swartland for Syrah and a particular approach to white blends. While this process is starting to happen and is likely to continue, the associations are as yet necessarily tentative and exploratory, and far from exclusive, let alone definitive. The dominant practice remains for wineries from large to small to produce a fairly wide range of wine, although this is also starting to change, as individual estates discover what their climates and soils do best and concentrate on that. But as many will claim, some climates and soil serve a diversity of cultivars, and the large ranges persist, though generally on a less extensive scale than in the 1980s.

If the total size of the South African vineyard did not change drastically in the first fifteen years of the new South Africa, that is not true of its nature, particularly in terms of varietal composition—precursor, of course, to changes in the wine being made. The most obvious shift has been from the overwhelming preponderance of white grapes: in 1993 white grapes occupied 81 percent of the total vineyard area, much of the harvest destined for distillation. International demand required more red wine than the Cape was producing, especially of the best-known varieties, and the pattern started changing rapidly. There was even something of an overcorrection. In 2005 the white grape percentage was down to 54.3, but it rose again, to 55.6 percent in 2011. Especially because a good deal of the white grape crop goes into brandy and comes from high-yielding vineyards, the proportion of white wine to red is higher than the proportion of the respective vineyard areas: white wine is now 62.4 percent of total production.

The prime grape victim in the great color shift was Chenin Blanc. At just over 18 percent it remains by far the most planted variety, down from about 33 percent in 1993 (its high point was five years previously). Patterns of change are discussed more fully in chapter 3, but it is worth noting here how planting patterns have responded to the demand of international markets for wines from the best-known varieties, especially red wine grapes. In terms of vineyard area Cabernet Sauvignon grew from 5.5 percent of the total in 1993 to 12 percent in 2011, Syrah from 1.0 percent to 10.3 percent, Merlot from 1.8 percent to 6.4 percent. Of the important white grapes, Sauvignon Blanc went up from 4.5 percent to 9.6 percent and Chardonnay from 3.2 percent to 8 percent.

As for managing these vineyards, viticulture has improved greatly in recent years. For one thing, there are now many more professional viticulturists than there were, although it must be said that they are unfortunately generally less appreciated than winemakers, are sent abroad less often to gather expertise, and are less well paid. Francois Viljoen, from the country’s most important viticultural consultation service and one of the country’s foremost viticulturists, points out that when he started work in 1986 there were some twenty-five trained viticulturists in the Cape; the number rose to probably more than forty by the turn of the century; today he estimates there are about eighty—not including those formally untrained but with great local and international experience. And the latter category is, in fact, vital at the most ambitious end of wine production, for it’s certain that most of the Cape’s best producers have a closer link between cellar and vineyard work than ever before. Nonetheless, the cult of the winemaker is as established a religion in South Africa as it is elsewhere in the New World. At wine competitions it is invariably the winemaker called up to receive the medal and then, usually, to mouth platitudes (which he—usually he—possibly even believes) about “wines being made in the vineyard.” In fact, in many of the foremost wineries, and certainly the smaller ones, it is nowadays common for the cellarmaster and viticulturist to be one person: the traditional vigneron of Europe, in fact (and the traditional wine-farmer of South Africa too, for that matter, though now hopefully on a rather more convinced and convincing level).

So far, so good, but two important negative factors in South African winegrowing must also be mentioned. While the shift in the vineyard to superior varieties is an undoubted improvement, bringing South Africa more in line with its international competitors, the limited choice of clonal material and the limited availability of less mainstream but high-quality grapes are problems. It is one of many shortcomings that can be ascribed to poor leadership from the KWV in its days of overlordship. Through much of the twentieth century in South Africa not only was clonal material sought and developed with the aim of maximizing yield rather than quality, but there was little useful experimentation in finding varieties well suited to the Mediterranean climate of the Cape. The difficulty of obtaining good and sought-after vines was made particularly clear in the 1970s and 1980s, when ambitious producers felt obliged to resort to illegal smuggling in response to a lack of suitable available material and to long bureaucratic delays in bringing vines though quarantine. Chardonnay was the variety most famously involved, and there was even a governmental commission of inquiry into the matter.

Systems were subsequently streamlined, but leadership, at least, remained lacking, and a number of varieties that should be available—from similar climates in Italy and Portugal above all—are not. This remains a big problem in taking development forward. Diversity within the vineyards is sorely lacking: the five most planted varieties occupy more than 60 percent of the vineyard area, the ten most planted occupy more than 85 percent. Most producers with ambitions to produce high-quality wines limit themselves to the same “big five” that the rest of the world also dutifully worships (and of course the market demanding what amounts to brand names is a real problem): Cabernet Sauvignon, Syrah, Merlot, Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc. Chenin Blanc and Pinotage are the most significant local additions to this depressingly small list. (See chapter 3 for further considerations on varieties and varietalism.)

Somewhat ironically, the marketing body Wines of South Africa (WOSA) uses “Diversity is in our nature” as a central slogan in its international campaigns. This diversity refers, of course, not to imported vines but above all to the Cape floral kingdom, the world’s smallest and incomparably richest: the Cape botanical region has 1,385 species per ten thousand square kilometers (the standard measure), while the second highest figure is 340, for the Neotropic floral kingdom (the Americas from the southern parts of North America southward). Generally difficult growing conditions and a wide range of topographical and climatological factors give rise to this diversity, and since this is where most of the wine lands are situated, WOSA not unreasonably encourages a perceived alignment between the natural beauty and biodiversity of the wine lands and the image of South African wine. The link has been made more profound since 2004 through the Biodiversity and Wine Initiative, a partnership between the wine industry and important environmental bodies that encourages wine farmers to set aside land for encouraging natural flora, in a situation where invasive plant species as well as agriculture and urban creep have severely compromised the natural environment. The program seems successful, with 174 members formally conserving more than 130,000 hectares of land by 2012. One of the largest (and richest) participants, Vergelegen, in 2004 began an ambitious ten-year program to clear alien vegetation from 2,000 hectares of its land and restore the natural flora and fauna to a pristine state; leopards and honey badgers are among the more spectacular creatures caught on Vergelegen’s infrared camera installations these days. But a rare plant or bird secure in a hectare of wetland whose preservation in pristine condition the program has encouraged is as heartening.

Another expression of concern for the environment in the Cape wine industry has been the continuing and developing success of the voluntary Integrated Production of Wine scheme since 1988. Certification according to established international wine industry environmental sustainability criteria is carried out by an office responsible to the Wine and Spirit Board, which evaluates and audits members’ practices in vineyards and cellars. A seal for the bottles of qualifying members was introduced for the 2010 harvest year.

At least as significant a problem as the lack of varietal diversity in the Cape and the lack of investigation into the most suitable varieties for its conditions is the continuing widespread presence of leafroll virus. A major dereliction of the KWV’s duty as industry leader in the twentieth century was its lack of assiduity (to put it generously) in attempting to solve the problem. To the casual wine-lands visitor in late summer the problem, in fact, looks nothing other than charming, as it spreads the loveliness of autumn coloring across the landscape. But unfortunately the color change is spreading rather earlier than the season warrants: virus-affected vines will not ripen fruit as well as clean vines with green chlorophyll surging in their leaves. While a little retarding influence on ripening can in some vintages be a useful thing (while infection levels are low), the wine made from heavily affected vines is not immune from unattractive associated flavors—stewed rhubarb, perhaps! The useful life of infected vines is much more limited, too—farmers are lucky if they will produce commercially viable crops until they are twenty years old, which would give them only twelve to fifteen years of good-quality harvests. Frequent replanting adds greatly to the expense of grape farming; it also denies the possibility of making wine from old vines, which are often associated with concentrated and finer flavors.

The problem is a large and complex one, but recently there has been significant progress in developing techniques to eliminate the virus and to at least ensure that virus-free material (both rootstocks and vines of the desired variety) can be supplied for planting. After that, it is up to the farmer to control the almost inevitable reinfection (which is spread mostly through the agency of the mealybug). Prevention of leafroll virus is something that requires determination, dedication, and hard work in South Africa, and is only now becoming widespread. Few vineyards can genuinely be claimed as “virus-free” (though heavy infection is greatly reduced)—and only vineyards subjected to continual scrutiny, careful preventive measures, and ruthless replacement of any infected vine are likely to remain so.

THE SOCIAL LANDSCAPE

Understandably, considering South African history, the social structure of the wine industry here is more closely scrutinized than in most parts of the world. And if slavery cast a long shadow over the wine industry after its abolition in 1834, so too has apartheid after the arrival of formal democracy in 1994. Most laborers, but precious few people at more exalted levels, in the wine cellars and vineyards of the reborn industry were and remain, in the fine racial distinctions that South Africa developed, “coloreds”—that is, of mixed race, mingling in themselves much of the industry’s human history. For wine industry workers (as for all engaged in agricultural labor), there was little protection from the apartheid-capitalist state. Wages were generally very low and housing poor. Accommodations were mostly on the farms; employees and their families were doubly dependent on the farmer.

The tot system (alcohol given to workers partly in lieu of wages, partly as a tactic of social control) goes back to the early days of slavery, and not everyone is convinced that it has disappeared even now—certainly it lasted long after it was legally abolished in 1962. Unquestionably its legacy does live on in the wine lands, in the endemic alcoholism that causes untold misery, and in the widespread fetal alcohol syndrome that blights so many lives. The wine industry is largely responsible for this legacy and has never adequately taken up the challenge of trying to address it—although, of course, it is a problem inextricably bound up with larger structures of poverty and degradation and requires a broad social solution, something much more thoroughgoing than moralizing, charitable patches, or simplistic attempts to medicalize the issue.

John Platter mused wryly on some of the social ironies of the wine industry in the new South Africa, in an “assessment of prospects in a sanctions-free world” in his 1996 Guide:

For connoisseurs of such things, the piquancy of how the new black government saved the white owned wine farming industry from growing insolvency is exquisite. It took a virtual teetotaling President Nelson Mandela—and an ANC-led government with a largely non-wine drinking, beer-thirsty African constituency—to bale out wine growers, mainly Afrikaner, mainly Nationalist Party voters who supported the 27-year incarceration of the man who opened the door to a sanctions-free, export-led recovery. No signs, of course, of discomfiture among the rescued—politesse deems it uncivil to even mention it.

The issue of “transformation” (a concept immediately understood by all South Africans to have racial connotations) is complex and sensitive, and it is impossible to do more here than highlight selected points within the complexities. But it is hard to avoid the conclusion that in most aspects of social relations, the wine industry is less transformed than many other sectors of South African society, despite some specific pockets of change and some broader areas of improvement. This is true at all levels, from the question of who owns land to the situation of the often unmotivated, inadequately trained people working on it.

In the absence of a radical national land agenda and because of the high value of most vineyard land and the high cost of working it, it is unsurprising that there has been virtually nothing in the way of land redistribution to alter the pattern of white ownership. A few ultrarich black individuals or black-involvement consortiums have acquired direct interest in or ownership of wineries: left-wing-politician-turned-capitalist Tokyo Sexwale, for example, some years back bought a wine farm in Franschhoek (though nothing has been heard of it or its wines since then); and a consortium he leads bought half of Constantia Uitsig. Somewhat less rich (as most people are, of course), former cabinet minister Valli Moosa now produces the Ecology range off his Bot River property, Paardenkloof; and members of the more modest Rangaka family have a vineyard in Stellenbosch and a brand, M’hudi, with the wines made at Villiera Estate.

Of rather more relevance to broader transformation, some significant “land and brand” projects have been undertaken. These are generally joint ventures between farmers and their workers, with the latter acquiring in various ways (government-sponsored or farmer-facilitated) part ownership of land and winery businesses, usually indirectly through shares or trust units. Examples of such partnerships include Thandi (vineyard ownership, with the brand part-owned by the large Company of Wine People), Tukulu (a joint venture among Distell, black entrepreneurs, and a workers’ trust), Thokozani (a brand with a 30 percent shareholding in Diemersfontein), and Solms-Delta (a passionate individual project of restitution).

Black ownership or part ownership of wine brands (without vineyard or winery), with wine sourced from established producers, is rather more common. Ses’Fikile, for example, was funded by Flagstone Winery (now part of the massive international Accolade, formerly Constellation Wines); its name, incidentally, means “we have arrived in style”! Yamme is a brand owned by a consortium of black women, as is Women in Wine. There are perhaps more than a dozen black-owned brands, aligned through the Black Vintners Association, which was founded in 2005.

This brings us closer to what has become the real focus of transformation in the wine industry: the Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) program, which has evolved to mean little more than equity ownership by black shareholders (whether capitalists or workers) in wine businesses of all sizes. A process toward drawing up some sort of charter for the industry was under way in the late 2000s. Drafts indicated that access to land would be a minor component of the charter, but any redistribution of such substantial assets was not in question. Also largely absent were matters affecting the majority of black people in the industry, such as working and living conditions.

Even without the existence of a formal charter, many large wineries and companies have already embarked on BEE deals, generally involving both employees, via a trust, and, proportionately more important, black investment companies. A highly controversial deal gave a black shareholder consortium 25.1 percent of the KWV—no doubt a pleasant symbol of the new South Africa, considering the deep implication of the KWV in its previous incarnation in the old South Africa. The controversy largely involved the role of the South African Wine Industry Trust (SAWIT), which was a body charged with, among other things, facilitating social transformation in the industry. SAWIT handed over its fund to a group of black entrepreneurs and others in order for them to buy the KWV stake. The money had originally come from the KWV, as the price it paid for being allowed to convert into a company, so there are some nice ironies here too: the KWV, in the end, in this way simply funded its own claims to political respectability through its acquisition of such a fine BEE component. As a result of becoming technically insolvent, SAWIT was no longer able to do much (it had never done much, in fact) in the way of wider empowerment of the poor and powerless within the industry. Meanwhile, the BEE package put together by Distell, while rather more “politically correct,” also involved a shareholding deal with outside investors as well as its own employees.

SAWIT had failed from the start to develop the skills of farmworkers and generally somehow “empower” them as it was supposed to. Other wine industry initiatives now tend to focus their transformation efforts less on need than on simple notions of “blackness” through BEE. This is a much more comfortable and easy process than grappling with the real problems faced by the majority of those involved in the industry—permanent workers and the temporary grape-pickers of harvesttime. But in some ways at least, the situation of all agricultural workers improved after a democratically elected government came to power after 1994. Notably, for the first time such workers were included in developing basic legal provisions to protect employees (health, insurance, work hours, leave, etc.), and a mandatory minimum wage (a very modest one) was promulgated. Of course, there are a number of relatively progressive farmers and businesses whose employment practices exceed basic legal requirements, but there are undoubtedly a number of others that fall short of meeting them. The Wine and Agricultural Ethical Trade Association (known as WIETA), which has various categories of membership, conducts audits prior to full accreditation, and this experience has shown just how little it can be assumed that national employment legislation is always complied with. Furthermore, as yet only a small proportion of wineries undergo WIETA’s audits—although this should change when the new “ethical seal” initiative, described below, is launched.

In the wine industry as a whole it is also clear, however, that some of the more positive aspects of rural paternalism are breaking down (partly in response to protective legislation, ironically): providing housing to workers on farms, for example, is becoming less common. So too is permanent employment—casualization of labor is increasing, as well as the use of labor brokers, some of whom are responding usefully to the seasonal nature of vineyard work, but others are simply making exploitation of workers more efficient by sparing farmers the trouble of grappling with the consequences of employing people. There is little effective trade unionism in the wine lands; organizing farmworkers is notoriously difficult.

Something of a breakthrough, perhaps, came in 2012, as a direct consequence of the previous year’s scathing report into the fruit and wine industries of the Western Cape by the respected international monitor Human Rights Watch. That report concluded (confirming what many knew, of course) that there remained significant human-rights problems for cellar and vineyard workers in the wine industry. It particularly blamed the state for not adequately monitoring its own laws and regulations. The anecdotal nature of much of the report’s evidence and other methodological inadequacies were arguably insufficient to support the generalizations it made and made it vulnerable to defensive attack. If there were real problems, it was a question of bad apples in the barrel, ran a common countering line.

A more thoughtful, positive response than the industry’s outrage came in early 2012 with the announcement of a new “ethical seal” that wineries complying with certain criteria can affix to their bottles. The scheme is being implemented under the aegis of WIETA, which announced that the purpose of the seal is “to acknowledge and accredit wineries and farms that follow ethical practices and to protect them from any potential negative publicity resulting from those who flout the law.” Already some major importers—notably Systembolaget in Sweden, but even supermarkets in the United Kingdom and elsewhere—had long been making demands that producers provide some proof that the conditions of workers met basic international standards. Fairtrade Foundation accreditation had been the most important indicator of this, but the new initiative should make adequate accreditation cheaper and easier. Most of the big players in the industry supported it, as did a number of nongovernmental organizations active in the area as well as the leading farmworker trade union. There seems reason to hope that the “ethical seal” will effect some improvement in worker conditions where it is needed.

PAST, PRESENT, FUTURE

The shadows—above all, perhaps, the racially informed inequality, but also problems like still-rampant virus—dim the brightness of the new world of South African wine, but do not obscure it. With a bit of perspective gained, it has now become possible to see and understand the developments that have taken place, and also to be not so overwhelmed by the brightness as to be unaware of the challenges. The context of South African society is indeed one of them, as is the international wine market and its demands. And there are other problems and opportunities that are local, even if they are not all entirely unique to here.

The history of South African wine is a long one by new-world standards—more than 350 years—and it contains within it the story of a great wine, Constantia, which remains something of an inspiration to modern South African winemakers, not least as an affirmation that high quality is possible at the foot of Africa. This does not exactly qualify as a wider tradition of greatness, however, and in fact the tradition of the Cape vineyards and wine business is above all one of poor-quality wine, heavily dependent on exports to a metropolitan market and always tending to overproduction—and overproduction of mediocrity. Without a great tradition, the task of building a great wine industry is daunting.

All the more remarkable, then, after so many years of mediocrity, was the rapidity of improvement at all levels since 1994. The change has largely been credited to the demands of a newly interested international market and the willingness and ability of South African wine-producers to respond, but that ability and willingness bear a little interrogation.

The ability is to a great extent the actual winegrowing potential of the land and the climate. This is the fundamental aspect that we sometimes vaguely call the terroir—the infrastructure, as it were, of viticulture, which interpenetrates with the human beings without whom terroir has no meaning beyond abstract potential. A useful sign of the potential is when “style” changes and quality remains. There are, for example, undoubtedly people who think that many Rustenberg Cabernet Sauvignons of that generally dull decade for the Cape, the 1980s, were (and even remain) very fine wines. Regardless of whether they are finer than the bigger, bolder, riper Rustenberg Peter Barlow Cabernet Sauvignons of two decades later, few who have drunk both would deny that both styles reveal a soil and a mesoclimate capable of producing good wine.

There seems to be something meaningful in the idea alluded to earlier, that the Cape is somehow naturally poised between (to employ reductive generalizations) the restraint and finesse of classic Europe and the powerful, fruit-driven exuberance of the New World. To an extent, as suggested earlier, it is a matter of winemaking traditions, but these traditions seem prompted by climate and soil. The assertive, sometimes flamboyant fruit that is found in California and Argentina, for example, is not easily found here, but nor is the equally forceful restraint (if that is not too much of an oxymoron) of France, while modesty in its best sense seems to come more easily here than it does in Australia—although, again, one needs to look beneath winemaking. A quality that many critics have noticed in many modern South African wines that are not pushed to excessive ripeness, especially whites, is a genuine freshness—and minerality for those who’ll countenance that description—connected to acid balance. This question of acid structure is particularly noteworthy, as it can point to the need to explore ways to understand and articulate a winegrowing potential. In the 1980s the academic insistence on understanding wine through analysis meant that virtually all local wines were routinely acidified—always to the point of technical safety and often to the point of hardness and imbalance. It was a given thing that the Cape’s acidic soils meant that the wines they produced were correspondingly lacking in acidity. But improved viticulture as well as more sensitive winemaking, the latter often achieved partly through the experience of working in Europe, means that now many of the Cape’s best wines go unacidified, and their natural balance—with a fine acidity—is all the better for it. This acid structure is one reason that white wines, where tannin is less of a vital component and acidity is more structurally exposed than in reds, are widely considered (by me for one) to be the stronger category in South Africa.

So much for inherent potential. The willingness of winemakers to learn to respond with new understanding—not just those who were young in 1994, but also many who had been making wine for twenty years or more—was much more than a technical response to a marketing challenge. It was part of, enlivened and encouraged by, a changing culture marked by huge social dynamism, which in certain ways carried along with it even the largely conservative individuals of the Cape winemaking establishment.

The larger bodies in which that conservatism found its most relevant wine-industry expression did, in fact, take longer to respond. The KWV was obliged to do so rapidly in terms of renouncing its dictatorial powers, but it took some fifteen years for it to show real signs of cultural and winemaking modernization in the best sense of that vague idea. Distell, the enormous wholesaler, which often still seems too monopolistically large for South Africa’s winemaking and wine-drinking good, changed more quickly, and started making better use of the range of vineyards at its disposal.

Nonetheless, it is to a few large private estates with uncompromising devotion to quality and, perhaps especially, to the small growers that one must inevitably look for innovation and real excitement at the highest levels of ambition. There are young—some very young—winemakers in areas like the Swartland who are trying radical experiments: a few fascinating barrels of old-vine Chenin Blanc fermented on its skins, or wines from rather despised grapes like Cinsaut and Carignan, picked unfashionably early, light-colored, and lacking massive concentration—and nevertheless rather profound and undoubtedly making for satisfying, pleasurable drinking. First-rate and fascinating wines have been made from old vineyards whose small yields had previously been lost in the massive anonymous vats of a cooperative. This is a trend of great significance, in indicating both an interest in the past and, even more, further recognition of the primacy of vineyard over cellar in producing fine quality. One of the Cape’s youngest wineries, Alheit Vineyards, declares its aim as being “to vinify extraordinary Cape vineyards,” and Chris and Suzaan Alheit have sought out old vines around the wine lands: “We love these old blocks not only because of their undeniable quality, but because they represent our heritage.”

So there is still fresh excitement in South African wine. It became apparent maybe fifteen years after the first important developments initiated in the early 1990s that a second, renewed qualitative shift had been taking place since the early 2000s. If the first phase of the vinous revolution basically involved catching up with accepted international standards and practices of growing and vinifying grapes, the second was predicated on responding to larger aspects of the Cape wine landscape: taking advantage of the new areas opened up to viticulture by the abandonment of the KWV quota system (Elim, Elgin, Cape Point, etc.) and reinventing and reinvigorating some of the old areas (Tulbagh, Swartland); making a useful start with the matching of terroir and grape variety; and forging styles of wine that accorded with what was offered by the (different) areas. A third phase of the revolution is now under way. One sign of it is the “discovery” of many scores of those old vineyards, because essentially this latest phase involves a crucial turn to detail—not in the winery, but among the vines. There are more professional viticulturists in the country than ever before, but of greater significance for the finest wines is the international experience brought to bear on local traditions of what we can no longer call straightforward winemakers—they are winegrowers, or vignerons, in the European tradition, uniting the processes of growing grapes and vinifying them, always with the emphasis on the former. An analysis of the real elite of Cape wine producers would show that the majority of them demonstrate this continuity between cellar and vineyard, often with the same person responsible for managing both.

Chris Alheit is “dead certain that the golden age of Cape wine is ahead of us.” Thanks, he suggests, to the pioneering work of figures like Eben Sadie and viticulturist Rosa Kruger (the woman responsible for tirelessly seeking out and “rescuing” so many old vineyards), “the Cape has never been so loaded with promise.” Another of the younger generation of winemakers remarked to me recently: “We have prepared the soil of the future, and we have made the roadway to it. Now, just the same as with democracy in this country, we still have to move forward to get somewhere really good.”