Читать книгу Dad’s Maybe Book - Tim O’Brien - Страница 19

13 The Magic Show (I)

ОглавлениеAs a kid, through grade school and into high school, my hobby was magic. I liked making miracles happen. In the basement, where I practiced in front of a stand-up mirror, I caused my mother’s silk scarves to change color. I used scissors to cut my father’s best tie in half, displaying the pieces, and then restored it whole. I placed a penny in the palm of my hand, made my hand into a fist, made the penny into a white mouse. This was not true magic. It was trickery. But I sometimes pretended otherwise, because I was a kid then, and because pretending was the thrill of magic, and because what seemed to happen became a happening in itself. I was a dreamer. I would watch my hands in the mirror, imagining how someday I might perform much grander magic, tigers becoming giraffes, beautiful girls levitating like angels in the high yellow spotlights, no wires or strings, just floating.

It was illusion, of course—the creation of a glorious new reality. White mice could fly, and dollar bills could be plucked from thin air, and a boy’s father could say, “I love you, Tim.”

What I enjoyed about this peculiar hobby, at least in part, was the craft of it: learning the techniques of magic and then practicing those techniques, alone in the basement, for many hours and days. That was another thing about magic. I liked the aloneness, as God and other miracle makers must also like it—not lonely, just alone. I liked shaping the universe around me. Back then, things were not always happy in our house, especially when my dad was drinking, and the basement was a place where I could bring some peace into my little-boy world, a place where I could make the sadness and terror vanish.

When performed well, magic goes beyond a mere sequence of discrete tricks. As an eight-year-old I was certainly no master magician, but I tried my best to blend separate illusions into a coherent whole, hoping to cast a spell, hoping to create a unified and undifferentiated world of magic. I dreamed, for instance, that someone in the audience might select a card from a shuffled deck—the ace of diamonds. The card might be made to vanish, then a rabbit might be pulled from a hat, and the hat might collapse into a fan, and the fan might be used to fan the rabbit, transforming it into a white mouse, and the white mouse might then grow wings and soar up into the spotlights and return a moment later with a playing card in its mouth—the ace of diamonds.

There were other pleasures, too. I liked the secrecy. I liked the power. I liked showing my empty hands when my hands were not empty. I liked the expression on my father’s face when I asked him to slip his head into my magical guillotine.

More than anything, my youthful fascination with magic had to do with a sense of participation in the overall mystery of things. At the age of seven or eight, when I learned my first few tricks, virtually everything around me was still a great mystery—the moon, mathematics, butterflies, my father. The whole universe seemed inexplicable. Why did adults laugh at unfunny things? Why did my dad get drunk? Why did everybody have to die, and why could not the laws of nature permit one or two exceptions? All things were mysterious; all things seemed possible. If my father’s tie could be restored whole, why not one day use my wand to wake up the dead?

After high school, I stopped doing magic—at least of that sort. I took up a new hobby, writing stories. But without straining too much, I can say that the fundamentals seemed very much the same. Writing stories is a solitary endeavor. You shape your own universe. You deal in illusion. You depend on the willful suspension of disbelief. You practice all the time, then practice some more. You pay attention to craft. You learn to show your hands to be empty when they are not empty. You aim for tension and suspense, as when a character named Betty slips her finger into a wedding ring, knowing she is not in love and never will be. You try to make beauty. You strive for wholeness, seeking unity and flow, each movement of plot linked both to the past and to the future, always hoping to create or to re-create the great illusions of life. “Abracadabra,” says the magician, and a silk scarf changes color. “By and by,” says Huck Finn, and you are with him as he boards his timeless raft. “Forgive me,” says your father, without ever quite saying it, and you do.

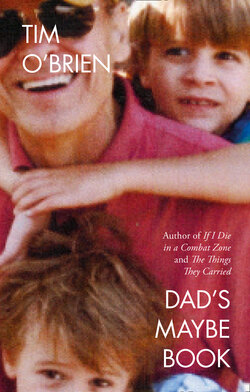

After an intermission of many decades, I’ve taken up magic again in a pretty serious way. Timmy and Tad live in a house cluttered with birdcages, top hats, wands, explosive devices, floating steel rings, spotlights, dancing canes, and innumerable decks of playing cards.

For the past eight months, a roulette table has occupied a substantial portion of our foyer. It’s an illusion I purchased secondhand from a retired Atlantic City magician—a prop that entirely blocks the passageway between our front door and living room. Visitors hesitate. The pizza delivery guy suspects illegal gambling. But Timmy and Tad take it all in stride, as if every father on earth spends his waking hours cussing at candles that fail to appear at his fingertips. (The trick isn’t easy. Six candles. Empty hands.) The boys politely take turns vanishing from a chair atop the roulette table; they tolerate the multiple miseries of contorting themselves inside black boxes; they roll their eyes when I tell them it’s time to be transformed into a gerbil. Magic bores them, I’m afraid. “If it’s really magic,” Tad said a few days ago, “why won’t you let me stand behind you when you make Mom disappear? Afraid I’ll see something?” This ho-hum, slightly hostile attitude sometimes does more than irk me. I get angry. These are children. Children are supposed to love magic. In part, I realize, Timmy and Tad have grown up in a household of appearing hotdogs and disappearing parakeets. They’ve become accustomed to miracles, and over the years, watching me practice, they’ve discovered the dull realities that make miracles appear to be miracles. They know what back-palming is. They know the technique behind a split-fan production. And from their own experience they know that the roulette table in our foyer is somewhat more than a roulette table. Who can blame them for not wanting to choose still another card—any card at all? Who can blame them for balking at another shuffle that isn’t actually a shuffle?

For the most part, the boys suffer in good-natured silence. They seem to understand, or at least intuit, that magic fills up an empty space inside me. Many, many years from now, long after I’ve vanished from their lives, Tad and Timmy may have a few blurred memories of their dad standing in front of the bathroom mirror, trying to pluck playing cards from the air, mostly failing, but still trying and trying, which is how it is right now as I try to pluck this maybe book from thin air.

Meredith and I, along with Timmy and Tad and a group of shanghaied friends, stage an elaborate show in our living room every couple of years. We’re amateurs—not great, but getting good. We float tables and children around the house. We appear and we disappear, sometimes in balls of fire, sometimes in large boxes, sometimes right before the eyes of the audience. We dance. We sing. We eat razor blades. A few years ago, we balanced Timmy on the point of a sword, spun him around on it, and then watched the sword penetrate his slim little body. During one disastrous rehearsal, we nearly gave the kid a real-life appendectomy. In other mishaps, we have almost suffocated one of our female magicians, almost decapitated another, and almost burned the house down. Alas, show biz.

As we prepare for each new show, our troupe of amateurs begins practicing about six months in advance, getting together every two weeks, putting in anywhere from three to seven hours of hard work at each session. There is a lot of tedium, a lot of frustration, and a lot of failure. (Again, much like writing stories.) Props stop functioning, threads break, secret doors don’t open, Timmy and Tad fall asleep backstage and need to be gently shaken and told it’s time to levitate.

In general, the members of our cast have amiably tolerated the long hours and numbing repetition. Some of them, I’m quite sure, don’t really care much for magic, but they know I care, and so out of great generosity they’ve thrown themselves into a pursuit that others might find frivolous, childish, and more than a little bizarre. Real-life teachers dress up as showgirls. A nurse practitioner dresses up as a wealthy casino minx. For months on end, at considerable sacrifice, the members of our troupe gamely toil to master their miracles and to perform them with a measure of grace and elegance. It isn’t easy. Angles of vision need to be taken into account. Posture—keeping the shoulders level—can determine success or failure. Too much light, or too little light, can be the difference between applause and grim silence. Despite these stresses, and despite the enormous chunks of time stolen from their lives, the members of our cast have come to appreciate that which I find so beautiful in magic—those moments when a half-dozen colorful parasols appear out of nowhere in swift succession, or when a glass of Beaujolais vanishes beneath a silk cloth, or when the ace of diamonds appears at the tip of a switchblade.

On show nights, as the living room fills up with ninety or so invited guests, our little troupe feels the jittery tension that any professional magician would feel. Backstage, we pace and mumble to ourselves. We rehearse moves in our heads. We feel dread fizzing up inside exhilaration. Although it’s only a living room magic show, we might as well be opening on Broadway or in Carnegie Hall or in a gilded theater on the Vegas strip.

And so it begins. The music comes on and we make our way out into a make-believe world, into a dead-end desert casino, where some of us deal blackjack and never lose, and where some of us pull wads of cash from the air, and where a croupier shoots fire from his roulette wheel, and where love is won and lost, and where a cocktail waitress sings to a cowboy doing rope tricks, and where a bartender produces bottles of wine from his bare hands, and where silver balls float to the ceiling, and where Lady Luck sets off her fateful explosions on a long-ago New Year’s Eve out in the desert of West Texas. Briefly, at least, it all feels real. The magic is happening.

Sixty-eight tricks later, it’s over. We blink and awaken from the dream.

Timmy and Tad, if you read this years from now, I want you to understand that my subject here is not magic. Nor is it storytelling. My subject is our longing for miracles. The human journey—yours, Timmy, and yours, too, Tad—is an immersion in all that is unknown and all that is unknowable: the unknown moment from now, the unknown yawn of eternity. Will I live on after I die? Will my children live happy lives? Will mankind survive the final flaring of the sun? Will Alice make her way out of Wonderland? At least in part, it is the mystery of the future that compels us to turn the pages not only of novels but also of our own lives. Unlike the animals, we conceive of tomorrow—tomorrow matters to us—and we spend a good portion of our time adjusting the present to shape the future, saving up for that vacation in Europe, heading off to church each Sunday in the hope that Saint Peter might issue his precious admission ticket. We yearn for the miracle of a happy ending. We’re human. We can’t help it. Likewise, on a less grandiose scale, we sometimes ask such questions as: Did Lizzie Borden take an ax and give her mother forty whacks? What happened to Amelia Earhart on her vanishing voyage over the South Pacific? What were Custer’s last thoughts at the Little Bighorn? Did Lee Harvey Oswald act alone on that November day in 1963? And late at night such thoughts can get pretty personal: Where exactly did things go wrong in my life? How did I end up in this strange bed, so restless, so shockingly alone? Why am I crying?

In the end, Tad and Timmy, we are mysteries even to ourselves. We may speculate, of course, and we may try to disentangle the microscopic threads of history and conscience and motive, but who among us really knows why we do the things we do or why we think the things we think? Is it not guesswork? And beyond that, what about the mysteries of the people all around us—our fathers and mothers, our children, our lovers, our friends? Is not each of us encased inside a leaden skull? Are we not all in solitary confinement? In her novella The Touchstone, Edith Wharton writes: “We live in our own souls as in an unmapped region, a few acres of which we have cleared for our habitation; while of the nature of those nearest us we know but the boundaries that march with ours.” I cannot read your mind, Timmy, and you cannot read mine, Tad. Often you surprise me. Often you confuse me. Often I yearn to crawl inside your heads in search of some elusive ground zero, even knowing there is no ground zero, even knowing that minute by minute we all undergo endless modification. What was true five years ago, or even five minutes ago, is probably no longer true, and almost certainly no longer true in the same way. Yet I keep longing for a miracle. I want to live inside you. I want to swim through your thoughts and sleep in your dreams. What a magic show that would be.