Читать книгу White Like Me - Tim Wise - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеBORN TO BELONGING

“People who imagine that history flatters them (as it does, indeed, since they wrote it) are impaled on their history like a butterfly on a pin and become incapable of seeing or changing themselves, or the world. This is the place in which it seems to me, most white Americans find themselves. Impaled. They are dimly, or vividly, aware that the history they have fed themselves is mainly a lie, but they do not know how to release themselves from it, and they suffer enormously from the resulting personal incoherence.”

—JAMES BALDWIN, “THE WHITE MAN’S GUILT” Ebony, August 1965

IT IS NOTHING if not difficult to know where to begin when you first sit down to trace the story of your life. Does your life begin on the day you came into this world, or does it begin before that, with the lives of your family members, without whom you would never have existed?

For me, there is only one way to answer the question. My story has to begin before the day I entered the world, October 4, 1968, for I did not emerge onto a blank slate of neutral circumstance. My life was already a canvas upon which older paint had begun to dry, long before I arrived. My parents were already who they were, with their particular life experiences, and I was to inherit those, whether I liked it or not.

When we first draw breath outside the womb, we inhale tiny particles of all that came before, both literally and figuratively. We are never merely individuals; we are never alone; we are always in the company of others, of the past, of history. We become part of that history just as surely as it becomes part of us. There is no escaping it; there are merely different levels of coping. It is how we bear the past that matters, and in many ways it is all that differentiates us.

I was born amidst great turmoil, none of which had been of my own making, but which I could hardly have escaped in any event. My mother had carried me throughout all of the great upheavals of that tumultuous year, 1968—perhaps one of the most explosive and monumental years in twentieth century America. She had carried me through the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy, through the decision by President Johnson not to seek re-election in the midst of the unfolding murderous quagmire in Southeast Asia, and through the upheaval in the streets of Chicago during that year’s Democratic Party convention. I think that any child born in 1968 must, almost by definition, be especially affected by the history that surrounded him or her upon arrival—there was too much energy floating around not to have left a mark.

Once born, I inherited my family and all that came with it. I also inherited my nation and all that came with that; and I inherited my “race” and all that came with that too. In all three cases, the inheritance was far from inconsequential. Indeed, all three inheritances were connected, intertwined in ways that are all too clear today. To be the child of Michael Julius Wise and LuCinda Anne (McLean) Wise meant something; to be born in the richest and most powerful nation on earth meant something; and to be white, especially in the United States, most assuredly meant something—a lot of things, truth be told. What those inheritances meant, and still mean, is the subject of this inquiry, especially the last of these: What does it mean to be white in a nation created for the benefit of people like you?

We don’t often ask this question, mostly because we don’t have to. Being a member of the majority, the dominant group, allows one to ignore how race shapes one’s life. For those of us called white, whiteness simply is. Whiteness becomes, for us, the unspoken, uninterrogated norm, taken for granted, much as water can be taken for granted by a fish.

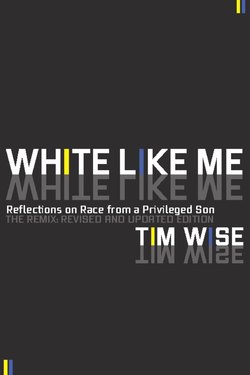

In high school, whites are sometimes asked to think about race, but rarely about whiteness. In my case, we read John Howard Griffin’s classic book, Black Like Me, in which the author recounts his experiences in the Jim Crow South in 1959 after taking a drug that turned his skin brown and allowed him to experience apartheid for a few months from the other side of the color line. It was a good book, especially for its time. Yet upon re-reading it ten years ago, one statement made by the author, right at the beginning, stuck in my craw. As Griffin put it:

How else except by becoming a Negro could a white man hope to learn the truth . . . The best way to find out if we had second-class citizens, and what their plight was, would be to become one of them.

Though I hadn’t seen the trouble with the statement at sixteen when I had read Black Like Me during the summer before my junior year, now as an adult, and as someone who had been thinking about racism and white privilege for several years, it left me cold. There were two obvious problems with Griffin’s formulation: first, whites could have learned the truth by listening to real black people—not just white guys pretending to be black until the drugs wore off; and second, we could learn the truth by looking clearly at our own experiences as whites.

Although whiteness may mean different things in different places and at different times, one thing I feel confident saying is that to be white in the United States, regardless of regional origin, economic status, sex, gender identity, religious affiliation, or sexual orientation, is to have certain common experiences based upon race. These experiences have to do with advantage, privilege (relative to people of color), and belonging. We are, unlike people of color, born to belonging, and have rarely had to prove ourselves deserving of our presence here. At the very least, our right to be here hasn’t really been questioned for a long time.

While some might insist that whites have a wide range of experiences, and so it isn’t fair to make generalizations about whites as a group, this is a dodge, and not a particularly artful one. Of course we’re all different, sort of like snowflakes. None of us have led exactly the same life. But irrespective of one’s particular history, all whites born before, say, 1964 were placed above all persons of color when it came to the economic, social, and political hierarchies that were to form in the United States, without exception. This formal system of racial preference was codified from the 1600s until at least the mid-to-late ’60s, when the nation passed civil rights legislation, at least theoretically establishing equality in employment, voting, and housing opportunity.

Prior to that time we didn’t even pretend to be a nation based on equality. Or rather we did pretend, but not very well; at least not to the point where the rest of the world believed it, or to the point where people of color in this country ever did. Most white folks believed it, but that’s simply more proof of our privileged status. Our ancestors had the luxury of believing those things that black and brown folks could never take as givens: all that stuff about life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Several decades later, whites still believe it, while people of color have little reason to so uncritically join the celebration, knowing as they do that there is still a vast gulf between who we say we are as a nation and people, and who we really are.

Even white folks born after the passage of civil rights laws inherit the legacy of that long history into which their forbears were born; after all, the accumulated advantages that developed in a system of racism are not buried in a hole with the passage of each generation. They continue into the present. Inertia is not just a property of the physical universe.

In other words, there is enough commonality about the white experience to allow us to make some general statements about whiteness and never be too far from the mark. Returning to the snowflake analogy, although as with snowflakes, no two white people are exactly alike, few snowflakes have radically different experiences from those of the average snowflake. Likewise, we know a snowflake when we see one, and in that recognition we intuit, almost always correctly, something about its life experience. So too with white folks.

AT FIRST GLANCE, mine would not appear to have been a life of privilege. Far from affluent, my father was an on-again, off-again, stand-up comedian and actor, and my mother has worked for most of my life in marketing research.

My parents were young when they had me. My father was a few months shy of twenty-two and my mother had just turned twenty-one when I was conceived, as legend has it in a Bossier City, Louisiana, hotel. Interestingly, my parents had opted to crash there during one of my father’s stand-up tours, because having first tried to get a room in nextdoor Shreveport, they witnessed the night manager at a hotel there deny a room to a black traveler. Incensed, they opted to take their business elsewhere. Little could they have known that said business would involve setting in motion the process by which I would come into the world. In other words, I was conceived, appropriately, during an act of antiracist protest.

My parents had dated off and on since eighth grade, ever since my father knocked over a stack of books that my mom had neatly piled up in the middle school library. My mom, having little time for foolishness, had glared at him, her flaming red hair and single upraised eyebrow suggesting that he had best pick them up, and then perhaps plan on marrying and starting a family. The relationship had been rocky though. My mom’s folks never took well to my dad, in part because of the large cultural gap between the two families. The Wises were Jews, a bit too cosmopolitan and, well, Jewish, for the liking of the McLeans. This is not to say that my mom’s parents were anti-Semitic in any real sense. They weren’t. But as with their views on race, the McLeans were just provincial enough to make the thought of an interfaith relationship difficult to swallow.

So too, they also worried (and in this they couldn’t have been more on the mark), that my father simply wasn’t a very suitable suitor for their little girl. Besides being Jewish, the problem was him. Had he been an aspiring doctor or lawyer, the McLeans might well have adored him. But a man whose dreams were of performing in comedy clubs? Or acting? Oh no, that would never do. And his father, though a businessman, owned liquor stores, and according to rumor, he might know and even be friends with mobsters. After all, weren’t all booze-peddlers mafiaconnected, or in some way disreputable, like Joe Kennedy?

In 1964, right before my parents were to begin their senior year of high school in Nashville, my mom’s folks moved the family to West Virginia, at least in part because West Virginia was far from Mike Wise. After graduation, my mom went to a two-year women’s college in Virginia, while my dad went West and obtained entrance to the prestigious acting program at Pasadena Playhouse. But within two years they were back together, my dad having given up on California when he realized that being discovered took time and more effort than he was prepared to put in. They married in May 1967, and spent the better part of the next year traveling around the country while my dad did comedy, finally ending up in that Bossier City Howard Johnson’s, where their bodies and the origins of my story would collide. My mom pregnant, it was time to move home and begin a family, and so they did.

All throughout my childhood, my parents’ income would have fallen somewhere in the range of what is politely considered working class, even though their jobs were not traditional working-class jobs. Had it not been for the financial help of my grandparents, it is likely that we would have been forced to rely on food stamps at various points along the way; most certainly we would have qualified for them in several of my years as a child. For a while my father had pretty consistent work, doing comedy or dinner theatre, but the pay was rotten. By the time I was in second grade, his employment was becoming more spotty, forcing my mom into the paid workforce to help support the family.

I spent the first eighteen years of my life in a perfectly acceptable but inadequately maintained 850-square-foot apartment with dubious plumbing, a leaky air conditioner, certainly no dishwasher or washing machine, and floor-boards near the sliding glass door in my bedroom that were perpetually rotting, allowing roly-polies or slugs to occasionally find their way inside. The walls stand out in my mind as well: thin enough to hear every fight my parents ever had and to cave in easily under the weight of my father’s fists, whenever the mood struck him to ventilate the plaster, as happened with some regularity. But even before the busted-up walls or leaky faucets at the Royal Arms Apartments, there had already been quite a bit of family water under the proverbial bridge. Examining the source of that stream provides substantial insight into the workings of privilege, and the ways in which even whites who lived in modest surroundings, as I did, had been born to belonging nonetheless.

Even if you don’t directly inherit material advantages from your family, there is something empowering about the ability to trace your lineage back hundreds of years, as so many whites but so few persons of color can. In 1977, my third grade teacher encouraged us to trace our family trees, inspired by the miniseries “Roots,” and apparently unaware of how injurious it might be for black students to make the effort, only to run head first into the crime of slavery and its role in their family background. The exercise provided, for the whites at least, a sense of pride, even rootedness; not so much for the African American students.

Genealogy itself is something of a privilege, coming far more easily to those of us for whom enslavement, conquest, and dispossession of our land has not been our lot. Genealogy offers a sense of belonging and connectedness to others with firm, identifiable pasts—pasts that directly trace the rise and fall of empires, and which correspond to the events we learned about in history classes, so focused were they on the narratives of European peoples. Even when we personally have no desire to affiliate with those in our past about whom we learn, simply knowing whence you came has the effect of linking you in some great chain of mutuality. It is enabling, if far from ennobling. It offers a sense of psychological comfort, a sense that you belong in this story known as the history of the world. It is to make real the famous words, “This land is my land.”

When I sat down a few years ago to examine my various family histories, I have to admit to a sense of excitement as I peeled back layer upon layer, generation after generation. It was like a game, the object of which was to see how far back you could go before hitting a dead end. Thanks to the hard work of the fine folks at Ancestry.com, on several branches of my family tree, I had no trouble going back hundreds, even thousands of years. In large measure this was because those branches extended through to royal lineage, where records were kept meticulously, so as to make sure everyone knew to whom the spoils of advantage were owed in each new generation.

Understand, my claim to royal lineage here means nothing. After all, since the number of one’s grandparents doubles in each generation, by the time you trace your lineage back even five hundred years (assuming generations of roughly twenty-five years each), you will have had as many as one million grandparents at some remove. Even with pedigree collapse—the term for the inevitable overlap that comes when cousins marry cousins, as happened with all families if you go back far enough—the number of persons to whom you’d be connected by the time you got back a thousand years would still be several million. That said, I can hardly deny that as I discovered those linkages, even though they were often quite remote—and despite the fact that the persons to whom I discovered a connection were often despicable characters who stole land, subjugated the masses, and slaughtered others in the name of nationalism or God—there was still something about the process that made me feel more real, more alive, and even more purposeful. To explore the passing of time as it relates to world history and the history of your own people, however removed from you they may be, is like putting together a puzzle, several pieces of which had previously been missing; it’s a gift that really can’t be overstated. And for those prepared to look at the less romantic side of it all, genealogy also makes it possible to uncover and then examine one’s inherited advantages.

Going back a few generations on my mother’s side, for instance, we have the Carter family, traceable to John Carter, born in 1450 in Kempston, Bedfordshire, England. It would be his great-great-greatgrandson, William, who would bring his family to the Virginia Colony in the early 1630s, just a few of twenty-thousand or so Puritans who came to America between 1629 and 1642, prior to the shutting down of emigration by King Charles I at the outset of the English Civil War.

The Carters would move inland after their arrival, able to take advantage in years to come of one of the New World’s first affirmative action programs, known as the “headright” system, under which male heads of household willing to cross the Atlantic and come to Virginia were given fifty acres of land that had previously belonged to one of at least fourteen indigenous nations whose members had lived there.

Although the racial fault lines between those of European and African descent hadn’t been that deep in the earliest years of the Virginia Colony—race-based slavery wasn’t in place yet, and among indentured servants there were typically more Europeans than Africans—all that would begin to change in the middle of the seventeenth century. Beginning in the 1640s, the colony began assigning blacks to permanent enslavement; then in the 1660s, they declared that all children born of enslaved mothers would be slaves, in perpetuity, themselves. That same decade, Virginia announced that no longer would Africans converted to Christianity be immune to enslavement or servitude. Then, in the wake of Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676, during which European and African laborers joined forces to overthrow the government of Governor Berkeley, elites began to pass a flurry of laws intended to limit black freedom, elevate whites, and divide and conquer any emerging cross-racial alliances between the two groups.

In 1682, the colony codified in law that all whites, no matter their condition of temporary servitude, were to be seen as separate and apart from African slaves, and that they would enjoy certain rights and privileges off-limits to the latter, including due process in disputes with their masters, and the right to redress if those masters abused them. Furthermore, once released from indenture, white servants would be able to claim up to fifty acres of land with which to begin their new lives. Ultimately, indentured servitude would be abolished in the early eighteenth century, replaced by a dramatic upsurge in chattel slavery. Blacks, along with “mulattoes, Indians, and criminals,” would be banned from holding public or ecclesiastical office after 1705, and the killing of a rebellious slave would no longer be deemed murder; rather, according to Virginia law, the event would be treated “as if such accident had never happened.”

The Carters, as with many of the Deanes (another branch of my mother’s family), lived in Virginia through all of this period when whiteness was being legally enshrined as a privileged space for the first time. And they were there in 1800, too—like my fourth great grandfather, William M. Carter—when a planned rebellion by Thomas Prosser’s slave, Gabriel, in Henrico County, was foiled thanks to other slaves exposing the plot. As a result, Gabriel was hanged, all free blacks in the state were forced to leave, or else face re-enslavement, and all education or training of slaves was made illegal. Paranoia over the Gabriel conspiracy, combined with the near-hysterical reaction to the Haitian revolution under way at that point, which would expel the French from the island just a few years later, led to new racist crackdowns and the extension of still more advantages and privileges to whites like those in my family.

Then there were the Neelys, the family of my maternal great-grandmother, who can be traced to Edward Neely, born in Scotland in 1745, who came to America shortly before the birth of his son, also named Edward, in 1770. The Neelys would move from New York’s Hudson Valley to Kentucky, where Jason Neely, my third great-grandfather, was born in 1805. The land on which they would settle, though it had been the site of no permanent indigenous community by that time, had been hunting land used in common by the Shawnee and Cherokee. Although the Iroquois had signed away all rights to the land that would become Kentucky in the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1768, the Shawnee had been no party to the treaty, and rejected its terms; not that their rejection would matter much, as ultimately the area came under the control of whites, and began to produce substantial profits for farmers like Jason Neely. By 1860, three years after the Supreme Court in its Dred Scott decision announced that blacks could never be citizens, even if free, and “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect,” Jason had accumulated eleven slaves, ranging in age from forty down to two—a number that was quite significant by local and even regional standards for the “Upper South.”

And then we have the two primary, parental branches of my family: the McLeans and the Wises.

The McLeans trace their lineage to around 1250, and at one point were among the most prosperous Highland clans in Scotland, but having allied themselves with Charles Edward Stuart (claimant to the thrones of England, Ireland, and Scotland), they lost everything when Stuart (known as Bonnie Prince Charlie) was defeated at the Battle of Culloden in 1746. The McLeans, as with many of the Highlanders, supported the attempt to restore the Stuart family to the thrones from which it had been deposed in 1688. Once the royalists were defeated and the Bonnie Prince was forced to sneak out of Scotland dressed as an Irish maid, the writing began to appear on the wall for the McLeans and many of the Highland Scots who had supported him.

With that, family patriarch Ephraim McLean (my fifth great-grandfather) set out for America, settling in Philadelphia before moving South in 1759. Once there, Ephraim would be granted over twelve thousand acres of land in North Carolina and Tennessee that had previously belonged to Catawba and Cherokee Indians, and which had been worked by persons of African descent for over a century, without the right of the latter to own so much as their names. Although the family version of the story is that Ephraim received these grants deservedly, as payment for his service in the Revolutionary War, there is something more than a bit unsatisfying about this narrative. While Ephraim served with distinction—he was wounded during the Battle of King’s Mountain, recognized as among the war’s most pivotal campaigns—it is also true that at least 5,000 blacks served the American Revolution, and virtually none of them, no matter the distinction with which they served, received land grants. Indeed, four out of five blacks who served failed to receive even their freedom from enslavement as a reward.

Ephraim’s ability to fight for the revolution was itself, in large part, because of white privilege. Although the Continental Congress authorized the use of blacks in the army beginning in 1777, no southern militia with the exception of that in Maryland allowed them to serve. Congress, cowed by the political strength of slave owners, as well as threats by leaders in South Carolina to leave the war if slaves were armed and allowed to fight, refused to press the issue. As such, most blacks would be kept from service, and denied the post-war land grants for which they would otherwise have been eligible.

In the early 1780s, Ephraim became one of the founding residents of Nashville, and served as a trustee and treasurer for the first college west of the Cumberland Mountains, Davidson Academy. On the board with him were several prominent residents of the area including a young Andrew Jackson, in whose ranks Ephraim’s grandson would later serve during the 1814 Battle of New Orleans, and alongside whom his greatnephew, John, would serve during the massacre of Creek Indians at Horseshoe Bend.

Ephraim’s son, Samuel (my fourth great-grandfather), was a substantial landowner, having inherited property from his dad. Although the records are unclear as to whether or not Ephraim had owned slaves, Samuel most certainly did, owning at least a half-dozen by the time of his death in 1850.

It has always fascinated me how families like mine have sought to address the owning of other human beings. Because it is impossible to ignore the subject altogether, those descended from slave owners opt instead to rationalize or smooth over the unpleasantness, so as to maintain the convenient fictions about our families to which we have so often become tethered. And so, in the McLean family history, compiled by a cousin of mine several years ago, slave-ownership is discussed in terms that strive mightily to normalize the activity and thereby prevent the reader from feeling even a momentary discomfort with this detour in an otherwise straightforward narrative of upright moral behavior. So we learn, for example, that Samuel McLean, my fourth great-grandfather, “owned much land and slaves, and was a man of considerable means.” This is stated with neither an inordinate amount of pride nor regret, but merely in the matter-of-fact style befitting those who are trying to be honest without confronting the implications of their honesty. Say it quickly, say it simply, and move on to something more appetizing: sort of like acknowledging the passing of gas in a crowded room, but failing to admit that you were the author.

A few pages later, the reader is then treated to a reproduction of Samuel McLean’s will, which reads, among other things:

I give and bequeath unto my loving wife, Elizabeth, my Negro woman, named Dicey, to dispose of at her death as she may think proper, all my household and kitchen furniture, wagons, horses, cattle, hogs, sheep, and stock of every kind, except as may be necessary to defray the expense of the first item above.

In other words, Elizabeth should sell whatever must be sold in order to hold on to the slave woman, for how would she possibly survive without her? But there is more:

I also give the use and possession of, during her natural life, my two Negroes, Jerry and Silvey. To my daughter Sarah Amanda her choice of horses and two cows and calves, and if she marry in the lifetime of my wife she is to enjoy and receive an equal share of the property from the tillage, rent and use of the aforesaid 106 acres of land and Negroes Jerry and Silvey, that she may be the more certain of a more comfortable existence.

Furthermore, if Sarah were to marry before the death of her mother, she and her husband were to remain on the property with Elizabeth so as to continue to benefit “from the land and Negroes.” However, if mom were to die before the wedding of Sarah, then the daughter was instructed to sell either the land or the slaves and split the proceeds among her siblings. Either way, Dicey, Jerry, and Silvey would remain commodities to be sure. Choosing freedom for them was never an option, for in that case, the McLeans might have to learn to do things for themselves: they might have to wash their own clothes, grow their own food, nurse their own wounds, make their own beds, suckle their own babies, and chop their own wood, all of which would make them less “certain of a more comfortable existence,” so it was out of the question.

To his son, Samuel D. McLean, Sam Senior bequeathed “a Negro boy named Sim,” who would then be handed down, not unlike an armoire, to his son John, my third great-grandfather. Then, according to family legend (and in what can only be considered the Margaret Mitchell version of the McLean’s history), Sim went happily off to the Civil War with his master. What’s more, we even have dialogue for this convenient plot twist, as Sim exclaims (and I’m sure this is a direct quote, transcribed faithfully at the time), “I’ve taken care of Mr. John all his life and I’m not going to let him go off to war without me.” Cue the harmonica. For his loyalty, we learn that “Sim got a little farm to retire on because the McLeans knew he would not get a pension of any kind.” No indeed, as property rarely receives the benefit of its very own 401(k) plan.

To his daughters, Sam McLean gave the slave woman Jenny and her child, and the slave woman Manerva and her child, and in both cases “any further increase,” which is an interesting and chillingly dehumanizing way to refer to future children. But we are to think nothing of this subterfuge in the case of the children of Manerva or Jenny. We are to keep telling ourselves that they are not people, and we are to keep repeating this mantra, no matter how much they look like people. Pay no attention to such small and trivial details.

Though many would excuse the barbarity of enslavement by suggesting that such an institution must be judged by the standards of its own time, rather than today, I make no such allowance, and find it obscene when others do so. It is simply not true that “everyone back then felt that way,” or supported slavery as an institution. Those who were enslaved were under no illusion that their condition was just. As such, and assuming that the slave owner had the capacity for rational and moral thought on par with his property, there is no excuse for whites, any whites, not to have understood this basic truth as well. Furthermore, even if we were only to consider the views of whites to be important—a fundamentally racist position but one we may indulge for the sake of argument—the fact would remain that even many whites opposed slavery, and not only on practical but also on moral grounds.

Among those who gave the lie to the notion of white unanimity—which notion has served to minimize the culpability of slave owners—we find Angelina and Sarah Grimké, John Fee, Ellsberry Ambrose, John Brown (and his entire family), and literally thousands more whose names are lost to history. Indeed, if we look hard enough we find at least one such person in my own family, Elizabeth Angel, whose opposition to the institution of slavery led her to convince her own family to free their chattel and to oppose enslavement at every turn. Though Elizabeth’s connection to the McLeans—her daughter was the wife of my great-great grandfather, John Lilburn McLean—and her opposition to an institution in which they were implicated might seem worthy of some exploration, in the official family history it is missing altogether. Rather than hold Elizabeth up as a role model for her bravery (which would have had the effect of condemning the rest of the family by comparison), the cousin who compiled the McLean biography passed over such details in favor of some random and meaningless commentary about the loveliness of her haberdashery, or some such thing.

But no excuses, no time-bound rationalizations, and no paeans to our ancestors’ kind and generous natures or how they “loved their slaves as though they were family” can make it right. Our unwillingness to hold our people and ourselves to a higher moral standard—a standard in place at least since the time of Moses, for it was he to whom God supposedly gave those commandments including the two about stealing and killing—brings shame to us today. It compounds the crime by constituting a new one: the crime of innocence claimed, against all visible evidence to the contrary.

In truth, even those family members who didn’t own other human beings had been implicated in the nation’s historic crimes. This was true, indeed, for most any southern family in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. State authorities made sure of that, by passing laws that enlisted the lower-income and middling whites in the service of white supremacy. In 1753, Tennessee passed its Patrol Act, which required whites to search slave quarters four times each year for guns or other contraband. By the turn of the century, and at which time large parts of my own family had made the trek to the state, these searches had been made into monthly affairs. By 1806, most all white men were serving on regular slave patrols for which they were paid a dollar per shift, and five dollars as a bonus for each runaway slave they managed to catch.

Throughout the period of my family’s settling in middle Tennessee, laws required that all whites check the passes of blacks they encountered to make sure they weren’t runaway slaves. Any white refusing to go along faced severe punishment. With no record of such racial apostasy having made it into our family lore—and surely such an example of brazen defiance would have been hard to keep quiet had it occurred—it seems safe to say that the McLeans, the Deanes, the Neelys, and the Carters all went along, regardless of their direct financial stake in the maintenance of the chattel system.

Likewise, although whites were members of nearly thirty antislavery societies in Tennessee by 1827, there is nothing to suggest that any of my family belonged to one. Nor is there anything to indicate that my kin objected to the uprooting of the Cherokee in the 1830s, even though many whites in the eastern part of the state did. And when Tennessee’s free blacks were stripped of the right to vote in 1834, or when the first Jim Crow laws were passed, also in Tennessee, in 1881, there is nothing in our family history that would portend an objection of any kind. In reading over family documents, handed-down stories and tales of all sorts, it is nothing if not jarring to note that race is almost completely absent from their discussions, which is to say that for so many, white supremacy was so taken for granted as to be hardly worth a fleeting moment of consideration, let alone the raising of one’s voice in objection. You can read their accounts of the time, and never know that you were reading about families in the United States, a society of institutionalized racial terror, where there were lynchings of black men taking place weekly, where the bodies of these men would be not merely hanged from trees but also mutilated, burned with blowtorches, the ears and fingers lopped off to be sold as souvenirs.

That was the way this country was when my family (and many of yours) were coming up. And most white folks did nothing to stop it. They knew exactly what was going on—lynchings were advertised openly in newspapers much like the county fair—and yet the white voices raised in opposition to such orgiastic violence were so weak as to be barely audible. We knew, but we remained silent, collaborating until the end.

In marked contrast to this tale, in which European immigrants came to the new country and were immediately welcomed into the emerging club of whiteness, we have the story of the Wises (not our original name), whose patriarchal figure, Jacob, came to the United States from Russia to escape the Czar’s oppression of Jews. Theirs was similar to the immigrant stories of so many other American Jews from Eastern Europe. You’ve heard the drill: they came here with nothing but eighteen cents and a ball of lint in their pockets, they saved and saved, worked and worked, and eventually climbed the ladder of success, achieving the American dream within a generation or two.

Whether or not it had been as bleak as all that, it certainly hadn’t been easy. Jacob’s arrival in 1907 was not actually his first time to make it to the United States. He had entered New York once before, in 1901, but had had the misfortune of cruising into the harbor only ten days or so after an American of Eastern European descent, Leon Czolgosz, had made the fatal decision to assassinate President William McKinley. McKinley had lingered for a week after the shooting, and died just a few days before the arrival of my great-grandfather’s boat. As the saying goes, timing is everything—a lesson Jacob would learn, sitting in steerage and coming to realize that he had been literally just a few days too late. So back he went, along with the rest of his shipmates, turned away in the shadow of Lady Liberty by a wave of jingoistic panic, anti-immigrant nativism, hysteria born of bigotry, and a well nurtured, carefully cultivated skill at scapegoating those who differed from the Anglo-Saxon norm. That Czolgosz claimed to be an anarchist, and thus his shooting of McKinley came to be seen as a political act, and not merely the lashing out of a madman, sealed Jacob’s fate for sure. To the authorities, all Eastern Europeans were to be viewed for a time as anarchists, as criminals, and later as communists. Czolgosz was to be executed, and tens of thousands of Eastern Europeans and other “undesirable” ethnics would be viciously oppressed in the following years.

The mind of a twenty-first-century American is scarcely equipped to contemplate just how long the trip back to Russia must have been, not merely in terms of hours and days, but as measured by the beating of one’s heart, the slow and subtle escape of all optimism from one’s tightened lungs. How painful it must have been, how omnicidal for Jacob, meaning the evisceration of everything he was, of everything that mattered to him—the extermination of hope. Though not of the same depth, nor coupled with the same fear as that which characterized the journey of Africans in the hulls of slave ships (after all, he was still a free man, and his journey, however aborted, had been voluntary), there must have been points where the magnitude of his despair was intense enough to make the distinction feel as though it were one without much meaning.

So he returned to Minsk, in modern-day Belarus, for another six years, it taking that long for him to save up enough money to make the journey again. When he finally came back, family in tow, it would be for keeps. His desire for America was that strong, borne of the belief that in the new world things would be different, that he would be able to make something of himself and give his family a better life. The Wise family continued to grow after his arrival, including, in 1919, the birth of Leon Wise, whose name was later shortened to Leo—my grandfather.

Jacob was the very definition of a hard worker. The stereotype of immigrants putting in eighteen hours a day is one that, although it did not begin with him in mind, surely was to be kept alive by him and others like him. There is little doubt that he toiled and sacrificed, and in the end there was a great payoff indeed: his children did well, with my grandfather graduating from a prestigious university, Vanderbilt, in 1942. What’s more, the family business would grow into something of a fixture in the Nashville community that the Wise family would come to call home.

But lest we get carried away, perhaps it would be worth remembering a few things about Jacob Wise and his family. None of these things take away from the work ethic that was a defining feature of his character, but they do suggest that a work ethic is rarely enough on its own to make the difference. After all, by the time he arrived in America there had been millions of black folks with work ethics at least as good as his, and by the time he passed at the age of ninety-three, there would have been millions of peoples of color who had lived and toiled in this land, every bit as long as he had. Yet with few exceptions, they could not say that within a mere decade they had become successful shop owners, or that one of their sons had gone on to graduate from one of the nation’s finest colleges. Even as a religious minority in the buckle of the Bible belt, Jacob was able to find opportunity off-limits to anyone of color. He may have been a Jew, but his skin was the right shade, and he was from Europe, so all suspicions and religious and cultural biases aside, he had only to wait and keep his nose clean a while, and then eventually he and his family would become white. Assimilation was not merely a national project; for Jacob Wise, and for millions of other Jews, Italians, and Irish, it was an implicitly racial one as well.

Even before assimilation, Jacob had been able to gain access to opportunities that were off limits to African Americans. His very arrival in the United States—as tortuous and circuitous as was the route that he had been forced to take in order to achieve it—was made possible by immigration policies that at that moment (and for most of our nation’s history) have favored those from Europe over those from anywhere else. The Naturalization Act of 1790, which was the very first law passed by the U.S. Congress after the ratification of the Constitution, made clear that all free white persons (and only free white persons) were to be considered citizens, and that this naturalization would be obtained, for most all whites, virtually as soon as we arrived. Yet, during the period of both of Jacob’s journeys—the one that had been cut short and the one that had finally delivered him to his new home—there had been draconian limits, for example, on Asian immigration. These restrictions would remain in place until 1965, the year his grandson, my father, would graduate from high school. If that’s not white privilege—if that’s not affirmative action of a most profound and lasting kind—then neither concept has much meaning any longer; and if that isn’t relevant to my own racialization, since it is the history into which I was born, then the notion of inheritance has lost all meaning as well.

And there is more of interest here too, as regards the Wise’s role in the nation’s racial drama. Though whites who came to America after the abolition of slavery can rightly claim they had played no part in the evil that was that particular institution, it is simply wrong to suggest that they are not implicated in the broader system of racial oppression that has long marked the nation. In addition to the receipt of privileges, which stem from the racial classification into which they were able, over time, to matriculate, there are occasionally even more active ways in which whites, such as the Wises, participated in the marginalization of black and brown peoples.

It was only a few years ago, during a workshop that I was attending (not as a facilitator but rather as a participant), that I really came to appreciate this fact. During the session, we had all been discussing our family histories, and at one point I mentioned, almost as an afterthought, that my comfort in and around communities of color likely stemmed from the fact that my paternal grandfather had owned and operated a business in the heart of Nashville’s black community for many years—an establishment I had visited dozens of times, from when I had been only a small child until I was a teenager.

Prepared to move on to another subject and wrap up my time to share, I was interrupted by a black man, older than myself, whose ears and eyes had quite visibly perked up when I had mentioned my grandfather and his business in North Nashville.

“I’m originally from North Nashville,” he noted. “What kind of business

did he have?”

“A liquor store,” I responded. “My family owned liquor stores all over town and my grandfather’s was on Jefferson Street.”

“Your grandfather was Leo Wise?” he replied, appearing to have known him well.

“Yes, yes he was,” I answered, still not certain where all this was headed.

“He was a good man,” the stranger shot back, “a very good man. But let me ask you something: Have you ever thought about what it means that such a good man was, more or less, a drug dealer in the ghetto?”

Time stood still for a second as I sought to recover from what felt like a serious punch to the gut. I could feel myself getting defensive, and the look in my eyes no doubt betrayed my hurt and even anger at the question. After all, this was not how I had viewed my grandfather—as a drug dealer. He had been a businessman, I thought to myself. But even as I fumbled around for a reply, for a way to defend my grandfather’s honor and good name, I began to realize that the man’s statement had not been a condemnation of Leo Wise’s humanity. It was not a curse upon the memory of the man to whom I had lovingly referred as Paw Paw all of my life. Anyway, he was right.

The fact is, my grandfather, who had spent several of his formative years living with his family on Jefferson Street, indeed made his living owning and operating a liquor store in the black community. Though the drug he sold was a legal one, it was a drug nonetheless, and to deny that fact or ignore its implications—that my grandfather put food on his family’s table (and mine quite often) thanks to the addictions, or at least bad habits, of some of the city’s most marginalized black folks—is to shirk the responsibility that we all have to actually own our collaboration. His collaboration hadn’t made him a bad person, mind you, just as the black drug dealer in the same community is not necessarily a bad person. It simply meant that he had been complex, like all of us.

The discussion led to the discovery and articulation of some difficult truths, which demonstrated how messy the business of racism can be, and how easy it is to both fight the monster, and yet still, on occasion, collaborate with it. On the one hand, my grandfather trafficked in a substance that could indeed bring death—a slow, often agonizing death that could destroy families long before it claimed the physical health or life of its abuser. On the other hand, he, unlike most white business owners who operate in the inner-city, left a lot of money behind in the community, refusing to simply abscond with it all to the white suburban home he had purchased in 1957, and in which he would live until his death.

Even the man who had raised the issue of my grandfather’s career as a legal drug dealer was quick to point out the other side: how he had seen and heard of Leo paying people’s light bills and phone bills, hundreds of times, paying folks’ rent hundreds more; how he paid to get people’s cars fixed, or brought families food when they didn’t have any; how he paid people under the table for hauling boxes away, moving liquor around, or delivering it somewhere, even when he could have done it himself or gotten another store employee to do it. The man in the workshop remembered how my grandfather would slip twenty dollar bills to people for no reason at all, just because he could. By all accounts, he noted, Leo had continued to feel an obligation and a love for the people of the Jefferson Street corridor, even after he had moved away. But what he had likely never noticed, and what I had never seen until that day, was that he and his commercial activity were among the forces that kept people trapped, too. Not the same way as institutional racism perhaps, but trapped nonetheless.

He had not been a bad person, but he had been more complicated than I had ever imagined. He had been a man who could count among his closest friends several black folks, a man who had supported in every respect the civil rights movement, a man whose proximity to the black community had probably done much for me, in terms of making me comfortable in nonwhite settings. But at the same time, he had been a man whose wealth—what there was of it—had been accumulated on the backs, or at least the livers of black people. Neither his personal friendships nor his political commitments had changed any of that.

That structural dynamic had provided him privilege, and it had been my own privilege that had rendered me, for so long, unable to see it.

LOOKING BACKWARDS IN time then, it becomes possible to see whiteness playing out all along the history of my family, dating back hundreds of years. The ability to come to America in the first place, the ability to procure land once here, and the ability to own other human beings while knowing that you would never be owned yourself, all depended on European ancestry.

Nonetheless, one might deny that this legacy has anything to do with those of us in the modern day. Unless we have been the direct inheritors of that land and property, then of what use has that privilege been to us? For persons like myself, growing up not on farmland passed down by my family, but rather, in a modest apartment, what did this past have to do with me? And what does your family’s past have to do with you?

In my case, race and privilege were every bit as implicated in the time and place of my birth as they had been for my forbears. I was born in a nation that had only recently thrown off the formal trappings of legal apartheid. I was born in a city that had, just eight years earlier, been the scene of some of the most pitched desegregation battles in the South, replete with sit-ins, boycotts, marches, and the predictable white backlash to all three. Nashville, long known as a city too polite and erudite for the kinds of overt violence that marked the deep South of Alabama or Mississippi, nonetheless had seen its share of ugliness when it came to race.

When future Congressman John Lewis, Bernard Lafayette, Diane Nash, James Bevel, and others led the downtown sit-ins against segregated lunch counters in February 1960 (two weeks after the Greensboro, North Carolina, Woolworth’s was similarly targeted by students from North Carolina A&T), the modern youth-led component of the civil rights struggle was officially born, much to the chagrin of local thugs who attacked the protesters daily. Someone had apparently forgotten to tell them, as they put out cigarettes on the necks of these brave students, that Nashville was different.

Of course, why would they think it was? Violence had marked resistance to the civil rights struggle in Nashville, as it had elsewhere. In 1957, racists placed a bomb in the basement of one of the city’s soonto-be integrated schools, and a year later did the same at the Jewish Community Center because of the role Dan May—a local Jewish leader and head of the school board—had played in supporting a gradual (and actually quite weak) desegregation plan. Although the bombers in those instances galvanized opposition to outright terrorist tactics, ongoing resistance to integration delayed any truly meaningful movement in that direction until 1971, when busing was finally ordered at the highschool level. It would be 1974, the year I began first grade, before busing would filter down to the elementary level. This means that the class of 1986, my graduating class, was the first that had been truly desegregated throughout its entire educational experience; this, more than thirty years after the Supreme Court had ruled that segregation was illegal, and that southern schools must desegregate “with all deliberate speed.” There had been nothing deliberate or speedy about it.

But when it comes to understanding the centrality of race and racism in the society of my birth, perhaps this is the most important point of all: I was born just a few hours and half a state away from Memphis, where six months earlier, to the day, Dr. King had been murdered. My mom, thirteen weeks pregnant at the time, had been working that evening (not early morning, as mistakenly claimed by Bono in the famous U2 song), when King stepped onto the balcony outside room 306 of the Lorraine Motel, only to be felled a few seconds later by an assassin’s bullet. Upon hearing the news, the managers of the department store where she was employed decided to close up shop. Fear that black folks might come over to Green Hills, the mostly white and relatively affluent area where the Cain-Sloan store was located, so as to take out vicarious revenge on whitey (or at least whitey’s shoe department), had sent them into a panic. No doubt this fear was intensified by the fact that the downtown branch of the store had been the first target for sit-ins in the city, back in December 1959, when students had attempted to desegregate the store’s lunch counters.

A minor riot had occurred in Nashville the year before the King assassination, sparked by the overreaction of the Nashville police to a visit by activist Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture), from the Student NonViolent Coordinating Committee, who would soon become “Honorary Prime Minister” of the Black Panther Party. Although the violence had been limited to a small part of the mostly black North Nashville community around Fisk University—and even then had been unrelated to Carmichael’s speeches in town, contrary to the claims of then-Mayor Beverly Briley and the local media—by the time King was killed, white folks were on high alert for the first signs of trouble.

That I experienced my mother’s bodily reaction to King’s murder, as well as the killing of Bobby Kennedy two months later, may or may not mean anything. Whether or not cell memory and the experiences of one’s parent can be passed to the child as a result of trauma, thereby influencing the person that child is to become, is something that will likely never be proven one way or the other. Even the possibility of such a thing is purely speculative and more than a bit romantic, but it makes for a good story; and I’ve never much believed in coincidences.

But even discounting cell memory, and even if we disregard the possibility that a mother may somehow transmit knowledge to a child during gestation, my experience with race predated my birth, if simply because being born to a white family meant certain things about the experiences I was likely to have once born: where I would live, what jobs and education my family was likely to have had, and where I would go to school.

On my third day of life I most certainly experienced race, however oblivious I was to it at the time, when my parents and I moved into an apartment complex in the above-mentioned Green Hills community. It was a complex that, four years after completion, had still never had a tenant of color, very much not by accident. But in we went, because it was affordable and a step up from the smaller apartment my folks had been living in prior to that time. More than that, in we went because we could, just as we could have gone into any apartment complex anywhere in Nashville, subject only to our ability to put down a security deposit, which as it turns out was paid by my father’s father anyway. So at least as early as Monday, October 7, 1968—before the last remnants of my umbilical cord had fallen off—I was officially experiencing what it meant to be white.

I say this not to suggest any guilt on my part for having inherited this legacy. It is surely not my fault that I was born, as with so many others, into a social status over which I had little control. But this is hardly the point, and regardless of our own direct culpability for the system, or lack thereof, the simple and incontestable fact is that we all have to deal with the residue of past actions. We clean up the effects of past pollution. We remove asbestos from old buildings for the sake of public health, even when we didn’t put the material there ourselves. We pay off government debts, even though much of the spending that created them happened long ago. And of course, we have no problem reaping the benefits of past actions for which we weren’t responsible. Few people refuse to accept money or property from others who bequeath such things to them upon death, out of a concern that they wouldn’t want to accept something they hadn’t earned. We love to accept things we didn’t earn, such as inheritance, but we have a problem taking responsibility for the things that have benefited us while harming others. Just as a house or farm left to you upon the death of a parent is an asset that you get to use, so too is racial privilege; and if you get to use an asset, you have to pay the debt accumulated, which allowed the asset to exist in the first place.

If you think this to be unreasonable, try a little thought experiment: Imagine you were to become the Chief Executive Officer of a multibillion dollar company. And imagine that on your first day you were to sit down in your corner-office chair and begin to plan how you would lead the firm to even greater heights. In order to do your job effectively, you would obviously need to know the financial picture of the company: what are your assets, your liabilities, and your revenue stream? So you call a meeting with your Chief Financial Officer so that you can be clear about the firm’s financial health and future. The CFO comes to the meeting, armed with spreadsheets and a Power Point presentation, all of which show everything you’d ever want to know about the company’s fiscal health. The company has billions in assets, hundreds of millions in revenues, and a healthy profit margin. You’re excited. Now imagine that as your CFO gathers up her things to leave, you look at her and say, “Oh, by the way, thanks for all the information, but next time, don’t bother with the figures on our outstanding debts. See, I wasn’t here when you borrowed all that money and took on all that debt, so I don’t see why I should have to deal with that. I intend to put the assets to work immediately, yes. But the debts? Nope, that’s not my problem.”

Once the CFO finished laughing, security would likely come and usher you to your car, and for obvious reasons. The notion of utilizing assets but not paying debts is irresponsible, to say nothing of unethical. Those who reap the benefits of past actions—and the privileges that have come from whiteness are certainly among those—have an obligation to take responsibility for our use of those benefits.

But in the end, the past isn’t really the biggest issue. Putting aside the historic crime of slavery, the only slightly lesser crime of segregation, the genocide of indigenous persons, and the generations-long head start for whites, we would still need to deal with the issue of racism and white privilege because discrimination and privilege today, irrespective of the past, are big enough problems to require our immediate concern. My own life has been more than adequate proof of this truism. It is to this life that I now turn.