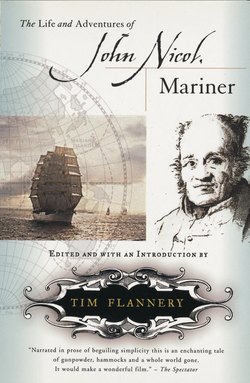

Читать книгу The Life And Adventures of John Nicol, Mariner - Tim Flannery - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Preface

ОглавлениеΤO THE PUBLIC it must appear strange that an unlettered individual, at the advanced age of sixty-seven years, should sit down to give them a narrative of his life. Imperious circumstances must plead my excuse. Necessity, even more than the importunity of well-wishers, at length compels me. I shall use my humble endeavour to make it as interesting as is in my power, consistent with truth.

My life, for a period of twenty-five years, was a continued succession of change. Twice I circumnavigated the globe; three times I was in China, twice in Egypt, and more than once sailed along the whole landboard of America from Nootka Sound to Cape Horn. Twice I doubled it—but I will not anticipate the events I am about to narrate.

Old as I am, my heart is still unchanged; and were I young and stout as I have been, again would I sail upon discovery—but, weak and stiff, I can only send my prayers with the tight ship and her merry hearts.

John Nicol

I WAS BORN in the small village of Currie, about six miles from Edinburgh, in the year 1755. The first wish I ever formed was to wander, and many a search I gave my parents in gratifying my youthful passion.

My mother died in child-bed when I was very young, leaving my father in charge of five children. Two died young and three came to man’s estate. My oldest brother died of his wounds in the West Indies, a lieutenant in the navy. My younger brother went to America and I have never heard from him. Those trifling circumstances I would not mention, were I not conscious that the history of the dispersion of my father’s family is the parallel of thousands of the families of my father’s rank in Scotland.

My father, a cooper to trade, was a man of talent and information, and made it his study to give his children an education suited to their rank in life; but my unsteady propensities did not allow me to make the most of the schooling I got. I had read Robinson Crusoe many times over and longed to be at sea. We had been living for some time in Borrowstownness. Every moment I could spare was spent in the boats or about the shore.

When I was about fourteen years of age my father was engaged to go to London to take a small charge in a chemical work. Even now I recollect the transports my young mind felt when my father informed me I was to go to London. I counted the hours and minutes to the moment we sailed on board the Glasgow and Paisley Packet, Captain Thompson master. There were a sergeant and a number of recruits, a female passenger, my father, brother and self, besides the crew. It was in the month of December we sailed, and the weather was very bad. All the passengers were seasick; I never was.

This was in the year 1769, when the dreadful loss was sustained on the coast of Yorkshire—above thirty sail of merchantmen were wrecked. We were taken in the same gale but rode it out. Next morning we could hardly proceed for wreck, and the whole beach was covered. The country people were collecting and driving away the dead bodies in wagons.

My father embraced this opportunity to prejudice me against being a sailor. He was a kind but strict parent and we dared not disobey him. The storm had made no impression upon my mind sufficient to alter my determination. My youthful mind could not separate the life of a sailor from dangers and storms, and I looked upon them as an interesting part of the adventures I panted after. I had been on deck all the time and was fully occupied in planning the means of escape. I enjoyed the voyage much, was anxious to learn everything, and was a great favourite with the captain and crew.

One of my father’s masters was translating a French work on chemistry. I went to the printing office with the proofs almost every day. Once, in passing near the Tower, I saw a dead monkey floating in the river. I had not seen above two or three in my life. I thought it of great value.

I stripped at once and swam in for it. An English boy, who wished it likewise but who either would or could not swim, seized it when I landed, saying ‘he would fight me for it’. We were much of a size. Had there been a greater difference, I was not of a temper to be easily wronged—so I gave him battle. A crowd gathered and formed a ring. Stranger as I was, I got fair play. After a severe contest, I came off victor. The English boy shook hands, and said, ‘Scotchman, you have won it.’

I had fought naked as I came out of the water, so I put on my clothes and carried off the prize in triumph—came home and got a beating from my father for fighting and staying my message; but the monkey’s skin repaid me for all my vexations.

I remained in London scarcely twelve months when my father sent me to Scotland to learn my trade. I chose the profession of a cooper to please my father. I was for some time with a friend at the Queensferry but, not agreeing with him, I served out my tedious term of apprenticeship at Borrowstownness. My heart was never with the business. While my hands were hooping barrels my mind was at sea and my imagination in foreign climes.

Soon as my period of bondage expired I bade my friends farewell and set out to Leith with a merry heart; and, after working journeyman a few months, to enable me to be a proficient in my trade, I entered on board the Kent’s Regard, commanded by Lieutenant Ralph Dundas. She was the tender at this time (1776) stationed in Leith Roads.

Now I was happy, for I was at sea. To me the order to weigh anchor and sail for the Nore was the sound of joy.1 My spirits were up at the near prospect of obtaining the pleasures I had sighed for since the first dawn of reason. To others it was the sound of woe, the order that cut off the last faint hope of escape from a fate they had been impressed into much against their inclination and interest. I was surprised to see so few who, like myself, had chosen it for the love of that line of life. Some had been forced into it by their own irregular conduct but the greater number were impressed men.2

Ogilvie’s revenue cutter and the Hazard sloop of war had a short time before surprised a smuggling cutter delivering her cargo in St Andrew’s Bay. The smuggler fought them both until all her ammunition was spent, and resisted their boarding her until the very last by every means in their power. A good many of the king’s men were wounded, and not a few of the smugglers. When taken possession of they declared the captain had been killed in the action and thrown overboard. The remainder were marched to Edinburgh Castle and kept there until the evening before we sailed. When they came on board we were all struck with their stout appearance and desperate looks; a set of more resolute fellows I have never in my life met with. They were all sent down to the press-room. The volunteers were allowed to walk the decks and had the freedom of the ship.

One night, on our voyage to the Nore, the whole ship was alarmed by loud cries of murder from the press-room. An armed force was sent down to know the cause and quell the riot. They arrived just in time to rescue, with barely the life, from the hands of these desperadoes, a luckless wretch who had been an informer for a long time in Leith. A good many in the press-room were indebted to him for their present situation.

The smugglers had learned from them what he was and with one accord had fallen upon him and beat him in a dreadful manner. When he was brought to the surgeon’s berth there were a number of severe cuts upon his person. From his disgraceful occupation of informer, few on board pitied him. After a few days he got better and was able to walk, but was no more sent down to the press-room.

Upon our arrival at the Nore, a writ of habeas corpus was sent on board for one of the smugglers for a debt. We all suspected him to have been the captain, and this a scheme to get him off from being kept on board of a man of war.

I was sent on board the Proteus, twenty-gun ship, commanded by Captain Robinson, bound for New York.3 The greater number of the smugglers were put on board the same vessel. They were so stout, active, and experienced seamen that Captain Robinson manned his barge with them.

We sailed from Portsmouth with ordnance stores and 100 men to man the floating batteries upon Lake Champlain.4

I was appointed cooper, which was a great relief to my mind, as I messed with the steward in his room. I was thus away from the crew. I had been much annoyed and rendered very uncomfortable, until now, from the swearing and loose talking of the men in the tender. I had all my life been used to the strictest conversation, prayers night and morning. Now I was in a situation where family worship was unknown and, to add to the disagreeable situation I was in, the troops were unhealthy. We threw overboard every morning a soldier or a sheep.

At first I said my prayers and read my Bible in private, but truth makes me confess I gradually became more and more remiss, and before long I was a sailor like the rest; but my mind felt very uneasy and I made many weak attempts to amend.

We sailed with our convoy direct for Quebec. Upon our arrival the men, having been so long on salt provisions, made too free with the river water and were almost all seized with the flux.5 The Proteus was upon this account laid up for six weeks, during which time the men were in the hospital. After having done the ship’s work, Captain Robinson was so kind as allow me to work on shore, where I found employment from a Frenchman who gave me excellent encouragement. I worked on shore all day and slept on board at night.

1 The Nore: a lighthouse near Hastings on the south-east coast of England.

2 These were men who had been kidnapped by press gangs and forced into naval service.

3 The American War of Independence had begun.

4 Lake Champlain: American Lake bordering New York and Vermont.

5 The flux: dysentry.