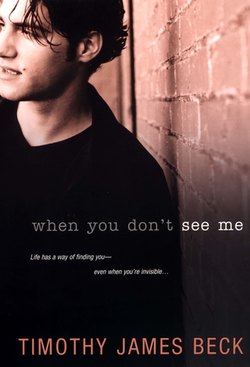

Читать книгу When You Don't See Me - Timothy James Beck - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2 A Man Could Get Arrested

ОглавлениеThere were many advantages to getting horizontal in bed with a man. Mainly, I appreciated the way my flaws weren’t as noticeable under covers. If a cop brought a guy to a lineup and asked him to point to the man who screwed him silly the night before, odds were good that the person singled out would be a muscular hunk, not some scrawny twink. I wasn’t like my beefy brothers—or my beefy gay brothers in the larger sense—and it mystified me when people felt compelled to point out how thin I was. Only the nagging mother of an overweight person would dwell on the obvious. But total strangers would tell a slender person to eat because he was too skinny. Or they’d use code words to express their criticism. Rangy. Lanky. Wiry. Gangly. Wasting away.

I wasn’t as thin as my height made me seem, and I had big bones. But even I had to admit that being sick had left me looking borderline emaciated. Still, no one ever complained about being wrapped up in my bony arms and legs in bed, Mark included.

I went to see Mark because my boss, Benny the Whiner, wouldn’t let me come back to work without a release from my doctor. I figured the clinic was closed on Sunday, but when I called the number from my prescription, I got the option of paging Mark. A couple cell calls and a brisk walk later, and I was at his apartment near Columbia University.

“I’m not sure you’ve had enough bed rest to go back to work,” Mark said after he let me in. He looked more appealing than he had on the day I’d met him. Kind of rumpled. Like he had no plans for Sunday except parking himself on the couch and eating junk food.

“Are you coming on to me? Shouldn’t you be worried about doctor-patient ethics?” I asked.

Ethics didn’t seem to be an issue. An hour or so later, the sheets were twisted around and between us like Morgan’s snakes. Which wasn’t an image I wanted in my head at that time. I started to tell Mark about my bizarre roommate, but he already knew from Roberto.

“How do you know Roberto, anyway?” I asked. “Is he a patient?”

“My current breach of ethics notwithstanding,” he said, while tracing my sternum with his finger, “if he were a patient, I wouldn’t talk about him. He’s a friend. How do you know him?”

“We went to school together,” I said. “Broadway High School for the Arts.”

“Right. I forgot how young you are,” Mark said.

He didn’t look too bothered by it, but if he was beginning to dwell on my flaws, he’d soon be stressing over my weight and shoving food down my throat. To head him off, I said, “I’m not young. I’m nineteen. Why? How old are you?”

“In gay years, I’m ancient. In doctor years, I’m young.”

“Gay years,” I mimicked. “I hate that. Sounds like dog years.” He only shrugged as a response, so I asked, “How young?”

“Thirty-one.”

“Ugh. It’s like I’m in bed with my uncle.”

“I can think of worse things,” Mark said.

“Do you know him? Is he your patient?”

“Roberto told me that Blaine Dunhill’s your uncle. You can’t be my age and gay in Manhattan without knowing who he is. Also, I’ve been part of AIDS and HIV fund-raisers with Daniel Stephenson.”

My uncle’s boyfriend, Daniel, was a C-list actor who’d been the focus of a very public outing a few years before. Even though it was old news, for a while he and Blaine had been the celebrity gay couple, constantly pictured or interviewed in Advocate, Out, the New York Blade, HX, and for some reason, Martha Stewart Living magazine.

“Their fifteen minutes were nearly over around the time I moved in with Blaine,” I said.

“When was that?”

“October”—I had to think a second—“of 2000.”

“Where’s your family? Or is that an insensitive question?”

“They’re in Wisconsin. I came out to them that fall. My father was completely not cool with it—he still isn’t—and my mother just hoped it would go away. My brothers are big jocks. Actually, my older brother was away at college, but Chuck—my twin—couldn’t deal. When our fights got physical, it seemed like a good idea for me to go away.”

Mark was a good listener, lying on his side and absently running his thumb up and down my arm while I talked. The swing I’d taken at Chuck came after years of dealing with my family’s crap. What made it different was that in the aftermath, I’d impulsively blurted out to my parents that I wanted to move in with my uncle.

When they sent me to my room so they could discuss the idea, I jumped online and researched art schools in Manhattan. I downloaded and printed a brochure from Broadway High School for the Arts. Next, I Googled Uncle Blaine. We’d spent a little time together and exchanged e-mails, but I thought it would be a good idea to see what I was attempting to get myself into. I knew he was an advertising executive for Lillith Allure Cosmetics, but I’d never bothered to check out his work.

With a few clicks of my mouse, I found his company’s Web site and saw pages of ads with beautiful photographs of models in extravagant settings. It was good stuff. Everything popped. My mind wandered, imagining the effort that went into putting together even a simple ad. The models, props, costumes, lighting, photographers, location, poses, product placement. The final result.

I wanted to be in the middle of that kind of creative buzz, surrounded by artistic energy and innovative people. I didn’t think I wanted to get into advertising, but if I was going to be sent away and hoped for a life in art, Uncle Blaine and his friends seemed like the kind of people I needed to be around. Plus they were a thousand miles from my family.

A few weeks later, I was in Manhattan, in public school for a couple months until the new term started at BHSA.

“Then I met Roberto,” I told Mark. “Our group of friends stayed tight even after graduation. When I moved out of my uncle’s place, Roberto was looking for a roommate, too.”

“What are you doing now? Are you in college? Art school?” Mark asked.

“I was at Pratt for a semester. Then I dropped out. Now everyone in my family is pissed at me.”

Mark’s phone rang, and while he talked a patient through some crisis, I thought about my confrontation with Blaine. I’d chosen to break the news over dinner in a restaurant, sure that my uncle wouldn’t make a scene in public.

“What do you mean you dropped out of college? Your second semester started two weeks ago. Are you telling me that you’ve been pretending to go?” Blaine hissed.

“It wasn’t for me,” I said in a way that I hoped sounded offhanded, as if I had everything under control. “It was boring. I want to start my life now.”

“Oh? How? Do you have a job lined up? A career?”

“Kinda. I got a job with I Dream Of Cleanie.”

“The gay maid service? You’re going to be a maid?” Blaine laughed and looked around, as if he expected Ashton Kutcher and a cameraman to jump out from behind a ficus. “That’s not a career, Nick.”

He was right. It wasn’t a career. Then again, I hadn’t said I intended to slave for I Dream of Cleanie the rest of my life.

Plus—I liked the job. It got me inside some really cool apartments, places I’d never get to see any other way. Not to mention that it gave me surprising insights into the dirty underbelly of human nature. The stuff you found under people’s beds….

It was that night, with Blaine at the restaurant, when I’d run into Kendra. She was our server. Her uniform was stained and slightly disheveled, like it realized it wasn’t up to par with the ritzy décor and was rejecting its wearer. She’d gotten the order wrong and begged us not to tell her manager.

“You’re not a vegetarian, are you? Thank God. I’m this close to being fired, and I really need this job. Even though I also work at Manhattan Cable. I’m looking for an apartment that I can afford in the city.”

“You are? Me, too.”

My uncle dropped his fork, but I refused to look at him. He could’ve offered to get me a job in Lillith Allure’s art department, but he didn’t. Fuck him.

“Sorry,” Mark said. “Where were we?”

I wanted to change the subject. “I rented Casablanca. Their world was crumbling around them. Their romance was sacrificed for a greater cause.” I made air quotes around “greater cause,” even though people who made air quotes annoyed me. “I don’t get it. How does Casablanca prove that anything lasts?”

“Forget the movie. I told you to listen to the lyrics of the song,” Mark said. “People will always fall in love. The world always welcomes lovers. You did hear the song, right?”

“The world welcomes lovers if they’re straight. The rest of us they’d sacrifice right along with the polar bears.” When Mark opened his mouth, I said, “Don’t tell me I’m too young to be cynical.”

“Actually, only the young can afford to be cynical,” Mark said.

“Yeah, you old dudes are always swooning over romance,” I said.

Mark attacked me to prove how young and energetic he still was. By the time I finally left, I was feeling less cynical but no older, since I was bearing my permission slip for Benny the Whiner as if I was still in grade school. In a brighter development, Mark and I had scheduled a movie date to see How to Lose a Guy in Ten Days. I tried not to see the title as a bad omen.

Especially when I came face-to-face with another bad omen on my walk home.

Even though I shared an island with a million and a half New Yorkers, there were certain people I saw over and over. Sister Divine was one of them. The first time I spotted her, I was with my friend Fred, who’d just paused outside St. John the Divine to light a cigarette. A woman shrouded in layers of dark fabric that resembled a medieval nun’s habit appeared in front of us. She pointed at Fred and yelled, “Your body houses twenty of Satan’s lieutenants! Cast them out and do God’s work!”

I made an effort to act indifferent and not gawk at her, but Fred was the real thing. He didn’t even blink. I fell into step next to him as he walked away from her.

“What the hell was that?” I asked.

He shrugged and said, “Twenty cigarettes to a pack, I guess. Do God’s work. I wonder what God pays. If there’s overtime. Just think about calling in sick to a deity. God would be all, ‘You’re not sick. You’re hungover. Get your ass to work. Stop stealing Mrs. Vela’s newspaper. And I wasn’t joking about that masturbation thing, mortal.’”

The first boy I dated after I moved to New York was Pete. Pete was also the first person who broke my heart, when he had a fling with Fred. Not because I was in love with Pete. Because I wished I’d gotten to Fred first.

Although I’d jeered about romance to Mark, I wasn’t against the idea. I just wasn’t the kind of person who constantly sized up the boyfriend potential of every guy I met. I didn’t make mental lists of what I did and didn’t want. But if I did, it would be easy to think of reasons why Fred shouldn’t be a boyfriend.

He smoked too much. He was always late. He thought monogamy was outdated. Actually, he practiced serial monogamy. Fred treated boyfriends like most people treated fashion: seasonally. Hot summer love migrated south at the first nip from autumn. And the man who blanketed Fred’s bed in winter would melt away like snow in the spring.

Fred was one of my few friends who had no inclination to do anything artistic. A year ahead of Roberto, Pete, and me at BHSA, he’d gone there only because the tuition was free. His uncle was the headmaster. He’d sneered at the school’s creative programs. Fred’s classes focused on the technical: set design or sound or lighting. He managed BHSA’s photo lab, although he had no interest in photography.

Now Fred worked at Starbucks, which in itself wouldn’t disqualify him as a boyfriend—after all, I bleached people’s bathroom grout—except that he enjoyed brewing java for the evil empire. He said the benefits rocked. He liked leaving the job when his shift was over and not thinking about it again until he went back. And if he felt like it, he could abuse the customers. Fred said they expected it, because most Starbucks employees were miserable and looking for a gig as an actor, musician, model, writer, illustrator—anything, it seemed, as long as it was creative and far from the grind of coffee beans.

Fred’s disinterest in all things artistic could be conversationally limiting. And he didn’t atone for it by having a flawless face or a great body. He wasn’t ugly, by any means. Just an average guy, the kind who played the sidekick in movies or was friends with your girl cousin.

But Fred had one habit that turned me on, even when it wasn’t directed at me. In a place where you could see or hear anything, so you tended to tune out everything, Fred paid attention. No cell phone, headset, or handheld anything ever got between him and another person. When he spoke to you, he looked at you. When you spoke to him, he heard you. His ability to completely focus on someone was erotic in a way that was beyond sex.

I never made the mistake of thinking he was flirting with me. Fred was my friend the same way Roberto was. I’d never tell Fred or anyone else how much time I spent thinking about the way his hair sort of curled against the back of his neck when he needed a haircut. Or how sexy I thought it was when he was mixing a Venti-whatever-latte and bit the tip of his tongue in concentration. Or that I once lied for three weeks and said I couldn’t find a jacket he left at Uncle Blaine’s apartment. I liked having it in the room with me. Maybe that was obsessive, but it was my little secret, and it hurt no one.

After the day Sister Divine accosted Fred, she seemed to pop up everywhere. I saw her outside Lincoln Center. At Seventy-ninth and Broadway. Skirting Columbus Circle. I wasn’t sure whether or not Sister Divine was homeless. Maybe she was just crazy. Whenever I saw her, she was skulking along, the same layers of black cloth shifting and settling around her. Until she’d go rigid and fix her gaze on some unwary tourist. Or anyone moving slowly—like a predator assessing the weakest potential prey. Then it would happen.

“Forty-two generals and six thousand lieutenants of Satan are in your body…. two hundred field generals…. five hundred captains…Repent! Cast out your demons! Do God’s work!”

Most people ignored her. I regarded her with affection, because she gave me a reason to call Fred. He enjoyed the Sister Divine updates. He’d picked up a transit map and map pins to mark my Sister Divine sightings, sure that a pattern would eventually emerge. Friends began placing bets on it. So far, the face of Jesus was losing to the face of Donald Rumsfeld two to one.

I was a few blocks from Mark’s when I saw Sister Divine. Or worse, when she saw me. She stopped, pointed at me, and shouted, “Legions of demons inhabit your body! Drive them out! Find the silver cord. Get inside yourself before it’s too late. Do God’s work!”

No one paid any attention to her, and I whipped out my cell so I could brag to Fred that I was possessed by more demons than he was.

“Oh, good,” he said. “I was starting to worry about her. Where are you?”

“I don’t know. Somewhere near Murray Hill.”

“Wow, she’s spreading faster than West Nile virus,” Fred said.

“She’s not that far from the first place we ever saw her.”

“What are you talking about? She’s practically—” He cut himself off with a sigh. “You said Murray Hill. What address?”

I looked around and said, “I don’t know. Somewhere near 119th and—”

“Never mind. Right letters, wrong neighborhood. Morningside Heights, Nick. It frightens me how little geography you know after almost three years here.”

“At least I know Harlem,” I muttered. “How many New Yorkers can say that?”

“Everyone. Harlem’s the old and the new black. You can’t swing a gold chain in Harlem without hitting a once or future president. And you do realize that Morningside—never mind. Where are you going now?”

“Home.”

“Good. Hook up with the roommates of your choice and meet us out later.”

“Who is us, and where is out?”

He rattled off a list of people from our recurring cast of friends, then said, “Cutter’s. Between nine and ten.” When I didn’t answer, he said, “Oh. It’s been so long that I forgot. Maybe Cookie forgot, too.”

Cutter’s was a dive on the Lower East Side. It was owned and operated by a retired Marine named John Cutter. Everybody called him Cookie.

Even though Cutter’s was quite a distance from the Hell’s Kitchen apartment where I’d lived with my uncle, I started going there with my friend Blythe not long after I moved to New York. She’d once lived in the neighborhood, so she knew the bar. Blythe was over twenty-one, and although I was only seventeen at the time, I never drank, so it wasn’t a big deal. When I started drinking, it still wasn’t a big deal. Cookie could barely be bothered to wipe down the bar or keep the toilet working, so he wasn’t exactly conscientious about checking an ID. Since several of my friends were underage like me, it was a good place for us.

Most of Cutter’s patrons were rough around the edges. Vets. Aging policemen. Ironworkers. We didn’t mingle with them, and they didn’t pay attention to us. We weren’t spoiled college kids. We didn’t make a lot of noise. No one got drunk or rowdy. We didn’t act like we were slumming. We were grateful to stay at our long table in the corner and shoot the shit. The working men stuck together at the bar or around the pool tables. We maintained a peaceful coexistence.

Blythe was the only person I knew who moved comfortably between the two groups. Blythe was an artist—an actual working painter whose work got shown and made money for her. She was our bohemian fairy godmother. Sometimes people didn’t take her seriously because she was around five feet tall and probably weighed ninety pounds. That was a mistake. Blythe had a take-no-prisoners disposition, and you crossed her at your own risk.

Something about Blythe endeared her to Cutter’s burly clientele. They looked out for her, but she had a way of looking out for them, too. Like Dennis Fagan, who was part of the reason I’d been kicked out of Cutter’s a few weeks before.

“What does that mean?” Kendra asked later, after I told her about Fred’s invitation. “Are we going, or aren’t we?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “I’d feel better if Roberto was with us. He’s bigger than me. He commands respect from the blue collars.”

She shrugged and said, “I haven’t seen him today. He’s probably at his mother’s.” She slapped at my hand when I started chewing a hangnail. “What did you do? Get in a fight with this Dennis guy?”

“Um, no,” I said. “Do I look dead?”

“So why’d you get kicked out?”

“It wasn’t my fault.”

“It never is.”

“Some guy was running his mouth about us. He was probably drunk. He made a couple comments that bothered me. I said something back. He called me a name, and Dennis clocked him.”

“Seems like the drunk guy and Dennis should have been the ones kicked out. Not you. I must be missing a lot of details.”

“Yeah, whatever,” I said. “I haven’t been back since. I don’t know if I’m banned for life.”

We stopped talking as Morgan walked through on her way to the kitchen. Roberto and I had gotten tired of our lack of privacy in Chez Snake Pit. While I’d been out, he’d finished installing walls made of sheets. Kendra had left me exposed by pulling back a sheet when she came in.

“Interesting portiere,” Morgan said, looking up at the aluminum poles that were suspended by chains from the ceiling. She fingered the sheets and said, “Not cheap. And not floral, thank the god of your choice. Are these from Drayden’s?”

When we were in school, Roberto’s financial contribution to the Mirones family had come from retail jobs—first at Lord & Taylor, then at Macy’s. His experience had helped him get his most recent job on the Visuals staff at Drayden’s, a newcomer to the department stores on Fifth Avenue.

“We can’t afford sheets from Drayden’s,” I said. “His mother got these from the hotel. And what’s a porter ray?”

“Portiere,” Morgan corrected. “It’s fancy talk for something hanging in a doorway. Roberto’s mother steals sheets from Four Seasons?”

Kendra said, “That sounds like she sells seashells at—”

“Of course she doesn’t,” I said. “They probably let the housekeeping staff buy old sheets or stuff that needs mending. I don’t know. Ask Roberto.”

“You should go out with us tonight,” Kendra said and gave Morgan one of her encouraging smiles. I imagined a force field of evil around Morgan that would deflect Kendra’s goodness and send it shrieking into the night, like a tranny prostitute with VD. “Nick was just telling me the story of steelworker Butch—”

“He’s an ironworker, and his name is Dennis.”

“—Cassidy and the Sunflower Kid,” Kendra finished. The expression on her face rattled me. Sometimes she seemed more passive-aggressive princess than dumb blonde. “C’mon. It’ll be fun!”

“Gosh, I don’t know,” Morgan said with exaggerated enthusiasm. “I’d go, but I don’t have anything to wear!” She pretended to flip back her hair with her hand and a toss of the head. Then she resumed her mask of Satan in human form and went into the kitchen.

“Do you think that means she’s not going?”

I looked at Kendra, trying to figure out if she was kidding. Although it was one of the most social exchanges I’d had with Morgan, there was no mistaking her message.

“Yeah. I think that’s what it means.”

“She can be such a buzz kill sometimes.” Kendra unfolded her legs and dramatically flung herself onto the futon. Then she started talking about her hair.

Even if we missed Roberto, we had to get out of there before Kendra turned my night into a slumber party.

It wasn’t really cold out, but Kendra and I were both dressed in heavier coats than most of the people we passed. I was trying to avoid a relapse, and Kendra said she needed a heavy coat to go with her outfit. Which made no sense. Nobody could see what she was wearing beneath it. And Cutter’s was always warm to the point of tropical, so she’d ditch it as soon as we were inside. Maybe she only had the one coat. Or maybe she felt the need to be buttoned up from head to toe.

“Do you get nervous walking through the barrio?” I asked.

“You make it sound like we live in a Santana video. No, of course I don’t get nervous,” she said with an anxious glance around. “You know it’s longer between buses on Sunday, right? I hate waiting for a bus.”

I decided to make a concession for the sake of her mental health. “If you’re that worried about it, we can take the subway. What’s the problem? Do you think you stand out because you’re so blond? So white? So walking like you’re spastic?”

“It’s the rats,” she said, doing another sidestep, although there wasn’t a rat in sight. “Anything above Ninety-fifth is rats, rats, rats.”

“Rats are everywhere. All you have to do is pay attention and don’t take stupid risks.”

“You’re being naive. We’re in Harlem. There’s gang graffiti—”

“Street art.”

“Trash on the streets—”

“Every street in the city has trash,” I protested.

“To be collected. Not to be blown down the sidewalks. Then again, I understand why people don’t use their trash cans. Yesterday I saw a chicken scratching around ours.”

I laughed and said, “It’s winter. No place in the city looks decent until spring. When Harlem thaws, you’ll change your mind. Roberto tells me there are block parties. Street festivals. Sometimes they close off streets for kids to play—”

“Yeah, that’s another thing,” Kendra said. “You don’t see so many kids anywhere else. The city is a lousy place to have a family. Families should live in Connecticut or Pennsylvania.”

I wanted to ask if her family was Republican. Or I could have told her that the only time I’d been mugged, I’d been outside an art gallery in the Village, which was probably Kendra’s idea of a safe neighborhood.

“Why are you so quiet? You artistic types are always brooding,” Kendra said.

“Brooding? Who uses that word in real life? I’m thinking.”

“You artistic types are always thinking,” she amended.

“You do know this isn’t a club we’re going to, right? We’re not having some Sex and the City moment. We’re not tweakers or club kids. Or even a bunch of overwrought, emo poets—”

“Disliking rats, free-range chickens who live in trash cans, and drive-bys doesn’t make me a snob,” Kendra said.

I put my arm around her as we walked. Regardless of what Kendra thought, anyone who paid attention to us at all seemed friendly. Older people even smiled, maybe mistaking us for a couple.

“I’m a reverse snob,” I said. “I’d rather walk these streets than walk into a loft in SoHo. Or a shop on Park Avenue. Talk about brutal people.”

“You don’t have to be rich to live where you don’t see homeless people sleeping on stoops,” Kendra said and pointed.

“You get what you pay—does she have clones? The bitch is everywhere.”

“Who?”

Sister Divine was sound asleep, and I couldn’t stop myself from checking out how she looked when she wasn’t screaming about demons. Without the intensity of her waking hours, the creases on her forehead and around her eyes weren’t as visible. She looked like a filthy fallen angel at rest.

As I stared at her, Kendra and the neighborhood around me faded. I remembered how I’d felt when I first moved to New York. The city had seemed magical. The crowded sidewalks, the rumble of the trains beneath the surface, the streets jammed with cars, cabs, and buses going places. I was always outside, always carrying my sketchbook. Even though I rarely left Midtown, there was inevitably something—an iron fence, a hidden garden, a bodega, or building masonry and adornments—with details that I couldn’t wait to get on paper. And the faces. After the sameness of people in the Midwest—or maybe I was just accustomed to them—I couldn’t get enough of the variety.

Sister Divine’s face had a childlike innocence as I looked at her, and I itched to have my sketchbook with me again. I wanted to protect her, even though nothing about her sleep showed fear. That comforted me, and I knew why.

There would always be before and after. I’d been in Manhattan for almost a year before September 11. A year when I immersed myself in every day and thought the adventure would last forever. Then came the nineteen months after.

Seeing Sister Divine asleep made it feel like before again. Like I was cradled by the city the way she seemed to be while lying there.

Kendra pulled impatiently at my sleeve, and the spell was broken.

We were greeted with warm, stale air inside Cutter’s. I held my breath, not knowing if Cookie would let me stay or make me bounce. Cutter’s was the kind of place where your eyes had to adjust once you went inside, no matter what time of day it was. But I spotted the ex-Marine watching us almost as soon as we went through the door. I kept my head low when I walked past the bar, where he was setting a beer in front of a guy with a hard hat hanging from the back of his stool.

“No trouble tonight,” Cookie said.

It was more of a decree than a warning. I got the idea that he didn’t blame me for what had happened the last time I was there. And I was sure he’d supported Dennis in that battle. I did a quick scan of the bar, but Dennis wasn’t with the rest of the blue collars.

I led Kendra to the usual table, where Fred was flanked by Roberto and Melanie. Melanie, who looked like a younger version of Meg Ryan, had been popular at BHSA. I wasn’t sure if she was in school anywhere now. A sculptor of rare talent, she could shape stone, wood, or metal into astonishing beauty and motion. It wasn’t often that she joined our group, but I always liked it when she did. She had a certain upbeat purity to her, a little like Kendra’s sunny disposition. I couldn’t quite put my finger on why the two were different. Sometimes Kendra had a childlike quality that I was pretty sure Melanie hadn’t had since she was about five.

I’d often thought that unusually talented people were robbed of childhood. It showed up in different ways in each of them, whether in their art or their personality. If Dr. Mark had been there, I could have told him that this was where my romantic streak showed itself. I was a fool for anyone gifted with creativity.

“You’re late,” Fred said, smiling at me in a way that I found sexy.

“Since you’re already here, I must be,” I said.

“My own special blend of spiced tea,” Melanie said, reaching to fill two empty cups as Roberto introduced her to Kendra. “Unless you’d rather have a beer?”

“Tea’s fine until I get warmed up,” Kendra said, shaking out of her coat. “My grandmother made her own tea. I was never allowed to have any, though.”

Everybody stared at her until I introduced her to the group; then I said to Fred, “You won’t believe this, but I saw Sister Divine again on the way here.”

“The homeless woman? What was up with that?” Kendra asked. “I thought you were going to kiss her or something.”

While Fred explained about Sister Divine, I sipped my tea, wondering why Cookie put up with us. He couldn’t make any money selling us hot water. I saw Roberto staring at me, but before I could ask him how he’d known to join us, I felt a presence swoop in behind me, and then two strong hands fell on my shoulders. As Blythe loudly pulled out the chair next to me and straddled it, I turned to see who’d taken possession of me.

“Davii! Aren’t you supposed to be on some remote island styling Lillith Allure models?” I asked.

“I needed him,” Blythe said, running a hand over her new spiky haircut. It was colored mostly dark red, with just the tips of the spikes hot pink. “He had to give me good luck hair.”

With one last squeeze of my shoulders, Davii slid into a chair between Melanie and me. More introductions were made for Kendra’s benefit, and Fred and I exchanged a glance. We both thought that Davii was possibly the hottest man we knew. Tall. Slender build. Icy blue eyes that contrasted with his nearly black hair. We competed to be the focus of his good energy, because it was calming and stimulating at the same time. As far as we knew, Davii was single, but Fred had never gotten any farther with him than I had.

“I only repaired what she did to her hair,” Davii was saying. “Then I escorted her to her opening.” He turned to me and added, “The photo shoot was rescheduled. Although I think they should do it here. How could a beach in Puerto Rico be more fabulous than Cutter’s?”

“Opening? Are you a performer?” Kendra asked Blythe.

“She’s the most amazing artist ever,” Melanie said.

“Ever?” Blythe asked and tried to look modest. “That may be stretching it.”

“Pay no attention to her false humility,” Davii said. “When we left, the Rania Gallery had already sold a half dozen of her paintings.”

“It was four,” Blythe said.

“Not that you noticed,” Roberto said, and I could sense the envy under his joking tone.

I understood his frustration. Roberto was happiest when he was consumed by his art. As a little kid, he’d been intrigued by stories about the Quetzal, a rain forest bird that was part of Latin American mythology. He’d gotten in trouble for drawing the bird on the walls of his bedroom. He shared the room with his brothers, so he tried to pin the blame on them. His childhood misbehavior had foreshadowed the times he’d gotten busted for defacing public property as a teenager. But when an artist didn’t have money for materials or a space to work in, tenement walls, dirty buildings, and sidewalks became a canvas for creativity, anger, and beauty.

Although Roberto’s art had become more abstract, I still saw evidence of the quetzal in his paintings. A bit of wise eye. A trace of wing. The colors of tail feathers. The bird was his muse, totem, and guide. But because Roberto had to work at Drayden’s to pay rent and to help his family, he wasn’t painting. It wasn’t surprising that he envied Blythe’s ability to support herself with her art.

However, at least he had a job that allowed him to express himself creatively. Drayden’s windows and displays were extremely elaborate and always changing. What kind of creative outlet did I have with my job? Sometimes I wrote my name in the cleanser before I started scrubbing.

Roberto had a unique vision and knew how he wanted to express it. When he did paint again, everything would probably just explode out of him. I envied him the way he envied Blythe. I could sketch anything. I could paint and get good grades in art classes. But everything I did was derivative of someone else’s work, and it bored me. Studying art or being expected to imitate the styles of other artists seemed like a sure way to extinguish whatever creativity I had. No matter what my uncle thought, dropping out of Pratt had been my first step toward self-preservation. I didn’t have a quetzal to inspire me, but there had to be something in the world that would help me develop an original vision.

I only half listened as the others talked about Blythe’s installation. I shifted my focus from Roberto to Melanie. Her sculptures had begun selling when we were still in high school, sometimes even before she finished them. I didn’t think she was making as much money as Blythe, but sooner or later, she probably would be. In the meantime, her parents paid for the Chelsea space where she lived and worked. She had a few neighbors who looked out for her. She was always trying to get Fred or me to hook up with them. A lot of our female friends seemed to share Melanie’s delusion that all single gay men were in desperate need of a boyfriend.

At least Kendra hadn’t tried to be my marriage broker. She was too focused on her own problems, and was struggling financially even more than I was. Even though she worked two jobs, I assumed she was always broke because she was putting herself through college. But Kendra wasn’t an artist. Her goal was to produce television shows, so going through Pratt’s Media Arts program made sense for her. Not only did she need to learn her craft, but she needed to make contacts.

As for Fred…I could stare at him as much as I wanted, since he was preoccupied with Davii. It was fun to watch him flirt. Fred lived the way most of us probably would if we believed fate was our guide. Things just worked out for him. Right now he might be pulling coffee at Starbucks, but I was sure that one day he’d luck into the perfect life for himself. Just like he’d gotten into art school through his uncle.

Or the way he’d gotten his apartment. A teacher from BHSA was on a yearlong yoga retreat in Okinawa, so Fred was living in his apartment, rent-free, to take care of his two cats. Being Fred, he’d almost turned it down because he couldn’t smoke there; then he found out it had a private rooftop terrace. The phrase that best applied to Fred’s life was one I’d learned from Aunt Gretchen: He could fall in a bucket of shit and come out smelling like a rose.

A wave of nausea washed over me, and all I wanted to do was leave. I felt selfish. Blythe was obviously in the mood to party, but I found it hard to celebrate her good fortune. When was I going to have good news to share? When would people be able to say, “Hey, Nick, that’s great news. I’m so happy for you.” I was tired of congratulating other people on their luck and was ready for some luck of my own.

The others didn’t notice how quiet I was. Or maybe they thought I was in a bad mood and wanted to give me space. I alternated between feeling sorry for myself, being angry for feeling sorry for myself, and being angry with everyone who was making me feel sorry for myself.

I mumbled something about getting a beer and left our table. Cookie tore his gaze from the basketball game on the TV over the bar when I slid onto a stool. He leaned forward with narrowed eyes, almost like he was mad at me. It was possible that I’d been wrong and he was holding a grudge.

“MGD, please,” I said.

“I told you before,” he said, “no ID, no drinks.”

“Huh?” Maybe he’d gotten me mixed up with someone else. He’d never asked for an ID from me. I glanced toward the men at the pool table, the only cops in the place. But they were off duty and weren’t looking our way.

“I can’t serve you without seeing an ID,” Cookie repeated.

“Fine.” I took out my wallet and handed him my fake ID.

“I’ll need to see that ID, too,” a man seated on the bar stool next to me said.

“Wh-wh-wh-what?” I stammered.

“Sorry,” Cookie said as the man reached over and took the ID from him.

I was such a dumbass. Of course Cookie hadn’t given a shit about my ID; he’d been trying to warn me. I should have just said I didn’t have my license with me and walked away.

“Peter?” The man squinted at the ID. “Would you care to step outside with me?”

“Outside? It’s cold outside. My coat’s over there. With my friends.” I tried to sound innocent. I glanced toward our table, unsure what they could do to help me, but at least Blythe, Davii, and Kendra were all of legal drinking age. Unfortunately, everyone at the table was oblivious to what was happening to me. I felt like I was in one of those nightmares where I screamed and no sound came out. “What are you, a cop?”

“Something like that,” he said. He gripped my arm and gave me a little push. I glanced again at my friends, but they still hadn’t noticed that I was being manhandled. I wondered why Fred had chosen this night to stop paying attention. But of course, he was. To Davii.

“Am I being arrested?” I asked.

“We’ll let them decide that at the precinct,” the man said. Then he repeated with sarcastic exaggeration, “Peter.”

The cold air blasted us as we went through the door, giving me a moment of clarity.

“Peter’s my friend,” I said. “I must have picked up the wrong license. Mine’s probably at home.”

“Like I said, we’ll let them figure that out at the precinct.”

He walked me to a van, where a uniformed cop opened a door so I could get in. Three other people barely glanced my way as I sat down. Two of them were girls with black-rimmed eyes and dye jobs as bad as Morgan’s. One of the girls was putting on dark lipstick, and the other was on her cell phone.

“Just tell Daddy to get there,” she snarled into the phone before snapping it shut.

“Hey, can I use that?” the only other guy asked. He was short, even thinner than I was, and covered with acne. Why had he imagined anyone would think he was old enough to drink?

The girl tossed him her phone with indifference. She looked at me and said, “You can use it, too. If they’re too stupid to take it away from me, I figure we can call whoever we want, right? I’m sure as shit not sitting in jail.”

“I’ve got my own,” I said, reaching into my pocket for my cell phone. I stared at it for a minute, realizing that more than anything in the world, I didn’t want to make my call.

I dialed the number and waited.

One ring.

Two.

Three.

“We’re not here. To leave a message for Daniel, press one. For Blaine, press two. For Gavin, press three. For anyone else, hang up and dial your number again.”

I pressed 2 and began, “Uncle Blaine? It’s Nick.”

Too bad I hadn’t specified good luck when I’d wished for some luck of my own.

A couple hours later, I was a free man, wondering how much Uncle Blaine had spent to buy my way out of being charged with anything. He hadn’t waited around to give me answers. I didn’t want the cops to change their minds, so I just walked out of the Ninth Precinct. Someone had brought my coat and left it for me. I buttoned it against the cold night air and splurged on a cab to take me home.