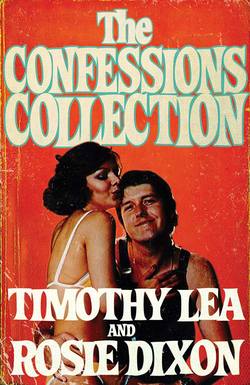

Читать книгу The Confessions Collection - Rosie Dixon, Timothy Lea - Страница 29

CHAPTER SEVEN

ОглавлениеAfter the Mrs. Dent incident, things quieten down a bit. Well, they have to, really, don’t they? It couldn’t go on like this without somebody having a hernia or a nervous breakdown, or something. Too exhausting for words, ducky! as Petal would say.

Garth comes back from holiday and takes Mrs. D. off my hands, amongst other things, and I go on with the likes of Miss Frankcom and the rest of the ‘halt and the lame’, as Crippsy calls them. No more is heard from the Major mob but I keep my eyes open because I know Sharp is not going to take the belting I gave him lightly. Dawn, who I have it away with occasionally, is more in touch with the Shermer Jet Set and she says that the whole of the side of his face is swollen up like a sockful of dough.

Days turn into weeks and during that time every A.D.I. in the School takes it in turn to supervise me occasionally like it says in the manual. Even Cronk comes out once or twice and I have the chance to find out what a lovable old cove he really is. Why he bothers with all that bullshit I don’t know, because anyone can see that behind all the huffing and puffing you could start cutting handkerchiefs out of his shirt tail and he wouldn’t say anything. I suppose it’s what they teach you in the army. Make the right noises and everybody will jump about for you—like the bloke I read about in a detective story once who had a safe that was operated by his voice saying ‘open shazam’ or something like that. What makes Cronk’s bustle and bluster more ridiculous is the scruffy bunch of blokes who operate for him. Crippsy looks like the ‘before’ part of a dandruff advertisement and the length of Garth’s hair would break a sergeant-major’s heart. Petal is a screaming pouf and Lester Hewett couldn’t see daylight between the springs of a chest expander. But somehow they do come over as a team, and they do look after each other. “Watch out for Flowers today,” Garth will say when Petal returns red-eyed from a weekend in London. “I think he’s having boyfriend trouble.” So everyone buys Petal tea and is sympathetic without bursting into tears when he comes into the room. Likewise, if Crippsy looks a bit the worse for wear, Petal or Lester will steer him off home and take over his stint with apologies for his unavoidable absence. It may just be their army background, but I think it’s something deeper than that. Over the weeks I discern that every A.D.I. in the School, apart from Cronk, was dishonourably discharged. They have all served with Cronk and he has obviously been the means of giving them a job in civvy street. Looking at them all, I come to the conclusion that failure can often bring closer together than success.

What they were all kicked out for I never find out. With Petal and Crippsy it is easy to guess, but with ‘Garth’ Williams and Lester Hewett it could be anything from pigeon toes to rape. Apart from asking them or feeding all the alternatives into the conversation and watching their faces, I can’t think of another way of knowing and I don’t fancy alternatives.

Almost before Cromingham’s excuse for a supermarket has stuck little pieces of cotton wool all over its windows, it is what Cronk calls ‘the fest-e-e-ve season’ and the E.C.D.S. holds an office party to prove how wrong he is. A great deal of South African sherry is drunk from chipped cups, Crippsy gets smashed and starts crying, Petal makes a pass at Garth, Lester pukes in the middle of Cronk’s message of Christian goodwill: “Backs to the wall, you play ball with me, and let’s all go forward to the promised land”; and I have it away with Dawn in the ‘out of order’ ladies’ on Cromingham station before I catch the three-thirty back to civilisation. Two things stick in mind about the whole pathetic business: some of the incredible things those birds had written on the bog walls and Dawn telling me she is three weeks overdue as the train pulls out of the station. Bloody nice Christmas present, isn’t it?

It doesn’t really need that to make Christmas with the folks as bloody as it is, but it helps. Sid and Rosie have gone to his parents, so I am left playing Wimbledon tennis between Mum and Dad, and going ape with the crystallised fruits which they have got because Mum remembers how much I used to like them when I was a kid. It makes it even sadder, somehow, the way they are so pleased to see me. I would like to be able to blame them for the whole turgid proceedings and it is a real effort having to watch the royal laugh riot from Sandringham without feeding it my usual chorus of eye-rolling yawns. Dad’s eyes close and he starts dribbling down the front of his new Marks and Sparks pullover, which he will change on Monday, whilst Mum’s expression registers the kind of blind devotion usually seen in dogs when it is getting near feeding time. I have been through the whole bad scene too many times and I can actually remember the first time I realised I was not enjoying it. I remember the feeling of guilt. It was like having a wank when you knew that it was an odds-on certainty that you would go blind if you did. This, and numerous other memories of past Christmases at the family Lea haunt me through the next few days until I can lie myself back to Liverpool Street Station with a carrier bag full of furry dates, burst figs and all the other rubbish that nobody else wants. I have told the parents that I have to work on New Year’s Eve but in fact I intend to go back to Cromingham and drown my sorrows between Mrs. Bendon’s legs. From a hundred and fifty miles away she has become a mixture of Marilyn Monroe and Silvano Manure, or whatever that big Italian bird’s name is, but, of course, when I get back I find a note explaining that she is still with her sister in Stockwell. Stockwell! I could weep. Three stations away on the Northern line and I have struggled all the bloody way back to living-death-on-sea. What a tragedy! I try to ring up Dawn but she has been invited to the New Year’s Eve ball at the golf club so I don’t even know if there is still an infant Lea up the spout. Bloody marvellous way to see out the old year, isn’t it?

I’d like to be able to report that a raving nympho with a bottle of Scotch in her hand threatened to slash her wrists if I don’t belt the arse off her, but in fact I end up in the public bar of the Sailor’s Return watching a bunch of half-pissed old tits link arms and sing Auld Lang Syne thirty seconds before the landlord shovels them out into the street. Thank you and good night!

Luckily, Dawn is not in the pudding club, so I can breathe again there, but when Mrs. B. returns from London there is a noticeable change in her attitude which does not bode well. She keeps mentioning some bloke she has met. “I don’t think Mr. Greig would agree with you there,” and makes dark references to needing the spare room at some not too distant date. The crowning insult comes when I ask her out for a drink and she says no: “Thank you, dear, but I’ve got a bit of a chill and I think I’d better stay at home. Another time, perhaps?” Of course, all this makes her so desirable I nearly explode every time I see her and I could kick myself for not having got across it when I had the chance.

The arrival of her daughter, on whom I had set high hopes, is a bit of an anti-climax, too. I had imagined myself staggering from one to the other or indulging in some monster orgy with both of them on the white rug in front of the ‘Cumfiwarm living-flame log-effect gas fire’, but Jenny sweeps through on the way to stay with friends at Brancaster—which is apparently the only place to have friends—and looks at me as if I’m somebody who brings in the logs in a Victorian melodrama, the kind of thing the BBC put on the telly every Sunday teatime.

Putting it mildly, she is a right pain in the arse and I spend a frustrating night thinking of ‘Mummy’ and her lying there in the big bed and of all the things I could be doing to them both. She is pretty, too, which makes it even worse.

But, fortunately, even my life does have its occasional moments of pleasure, and about the time that the first snowdrops are trying to force their stupid way through the rock-hard earth, a really nice piece of nooky drops into my lap. ‘Drop’ is not quite the right word, because for some time I have been conscious that Dawn has a lot of control over the way the new learners are allocated and is using it to divert anything that approaches being a good-looking bint from yours truly. I accept this because I can understand any woman wanting to hang on to me, and you can’t always have your cake and heat it, as King Alfred found out to his cost. (Ugh! Ed.)

I land up with Mrs. Carstairs because there is no alternative available. Garth has the ’flu, Petal is in the South of France with one of his actor friends—bloody nice being a pouf, isn’t it?—and the other two are booked up to the eyeballs, so Dawn has to grin and bear it.

Mrs. Carstairs makes Mrs. B. sound like a nun that has taken a vow of silence. From the first moment she rears up like a female polar bear in the E.C.D.S. reception, covered from head to toe in furs, she never stops rabbiting.

“You must think it absolutely amazing that anyone of my age doesn’t know how to drive,” she yodels as we sweep through the door with me trying to keep up with her. In fact, I would never have given it a thought, but I don’t have time to tell her because she is already trying to climb into the driver’s seat.

“If you haven’t driven before, I think we’d better start somewhere a little less crowded,” I suggest, steering her across to the other door.

“You’re probably right. It would be a bad advertisement if I killed somebody outside the School, wouldn’t it?”

I smile my ‘customer is always right’ smile and whip her up to the golf course. By the time we get there we have covered Vietnam, pollution of the environment and vivisection—or rather she has. Some of her sentences end in questions but I never have time to answer them because she has done that herself or started on something else. I don’t mind too much because I am busy lapping up her luscious contours. She has ‘lovely bones’, as my Mum is always saying about the nobs she so much admires, and big blue eyes you could comb your hair in. She must be over forty but is better preserved than Dad’s war record and her figure would win whistles on a girl of nineteen. What I like most about her is her smell. My hooter is very sensitive to the perfume a bird uses and it is a change to have something that tickles your scrotum rather than bashes you over the goolies with a rubber mallet.

She is also no fool and from the very first lesson performs a bloody sight better than most of the rubbish I get lumbered with. She is confident—possibly too confident, and takes in what you have to say very quickly. I can see what Garth means about bright pupils being death to a driving school. I learn that her old man is a director of ‘Python’s Pesticides’ and that she decided to take lessons because she was bored. Normally, my ears would have pricked up at the mention of the word ‘boredom’ because a bored woman is nine-tenths of the way towards taking her knickers off for you, even if she doesn’t know it at the time; but in this case there is something so assured and upper-class about Mrs. C. that I dare not entertain any hopes. Maybe I take after Mum, but an upper-class accent and a bit of swank always make me reach for my forelock.

“I tell you this at the risk of boring you out of your mind,” says Mrs. C., “but if I have to entertain one more Scandinavian expert on how to wage germ warfare on slugs I will go stark raving mad. I think it affects them, you know. I mean, working with pesticides. Something gets into them and makes them mentally and physically impotent.”

“Don’t you mean sterile?” I say, because all the long words I know come from the sex books I used to get out of Battersea Public Library.

“Mr. Lea,” she says, shaking her head in a mock-serious manner, “I fear that in my case it may be both. Very unkind of me to say so of the man who provides my wherewithal, but I think that somewhere along the line he’s been got at. I could probably make a fortune telling the story to the Sunday newspapers.”

“Why don’t you?”

“There is such a thing as family loyalty, Mr. Lea. And anyway, what’s a few thousand compared with George’s nice steady income? No, I’m very fond of sex, but there are other things—even if I can’t think of them at the moment. Oh, shit!” The last exclamation is caused by her nearly driving into an oak tree some fool has left littering the side of the road, and it is a few minutes before I hear of her other interests besides taking driving lessons.

“Don’t get the idea that I just sit at home twiddling my thumbs all day. I sit on a lot of committees, which is damn hard work—mainly because the rest of the old harridans on them are so obstreperous—and I paint. Very well, though I say so myself, although it could be better if George would let me indulge myself on a European tour. But he’s too mean—and too jealous; he imagines I would be pulling every Italian waiter in sight into my bed. Can you imagine?”

From the waiter’s point of view I can. Only too well. If it was me she wouldn’t have to break into a muck sweat to do it.

“I think it all goes back to the perils of Python’s Pesticides,” she continues. “When he was in the first flush of youth, so to speak, he was a most unjealous man—is there such a word? It doesn’t matter anyway. Now that sex has its problems for him, he’s suspicious of his own shadow—that’s rather good. Can you imagine being cuckolded by your shadow?”

I can’t, because I don’t know what ‘cuckolded’ means, but it sounds pretty painful and I nod my agreement.

“What kind of things do you paint?” I ask as we speed back to the E.C.D.S. with me safely behind the wheel.

“Oh, everything. Landscapes, still lifes—or should it be still lives?—nudes. It’s difficult to get models around here, you know. I think most of the locals think it’s ‘a bit orf’ or that I’m going to practise withcraft on them. George sits for me sometimes but he is clearly embarrassed, poor dear, and not very inspiring. Especially when he is poring over his balance sheets and sucking his teeth all the time. I know—” I can feel her eyes flitting over me and I tilt back my hear to tighten up the jaw muscles “—could you, I mean would you sit for me?”

“What? Me?” It is difficult to get exactly the right note of slightly confused amazement into my voice but I think I do it quite well. “I don’t know. I’ve never done anything like that before.”

“No experience necessary. Just keep reasonably still. I’d pay you, of course.”

“Well, I don’t know.” I pretend to be giving the matter serious thought.

“I’m sorry. I can see that you don’t really like the idea. I should never have asked. Look, can you drop me here? I want to pop into the butcher’s.”

“Oh no, I’d like to do it,” I blurt out. “When would you want me to start? I’m free most evenings, or there’s mornings or some afternoons.”

I feel I have overdone it a bit as soon as I close my mouth and Mrs. C. looks appropriately confused.

“Are you sure? You seemed so hesitant a moment ago.”

“Yes, well, I was trying to think what spare time I had in the next few weeks.”

“I don’t intend to cast you in bronze. I won’t be making much of a hole in your time off. Just an hour here and there. How can I get in touch with you?”

“I’m not on the telephone at my digs. You’d better mention it to me when you’re having your lessons.”

“O.K. I can leave a message at the School, can’t I?”

I don’t disagree with her but I can’t see Dawn responding very well to that. She looks me over pretty closely when I report back at the School as if checking that my flies are still done up and that I am not covered in lipstick, but it is Cronk who shows most emotion. He flashes out of his office as I go in and demands almost hysterically where Mrs. Carstairs is.

“Real feather in our cap, that one,” he tells me when he finds I haven’t driven her off the end of the pier. “If we can do a good job with her, we’ll be on the map and no mistake. Once she starts chatting to the top brass at Python’s they’ll all be down here. Directors’ wives, managers’ wives, right down to the shop stewards eventually. It’s up to you, lad. Pull out the stops on this one.”

I give him my plucky ‘do my best sir’ smile, borrowed from all those British war films you see on the telly and wink at Dawn, who scowls and looks the other way. Poor kid, I can understand how threatened she feels and she doesn’t know the half of it: me naked on some rug with Mrs. C. trying to stop the paintbrush dropping from her twitching fingers—my mind races away into overdrive as usual.

In fact, Mrs. C. hardly mentions her painting the next time I take her out and I am on the point of deciding she has thought better of it when a sour-faced Dawn hands me a piece of paper with a telephone number scrawled on it and tells me that “your fancy bit rang and asked you call her this afternoon.” This leads to a lot of leg-pulling from the rest of the lads, which I am secretly very pleased about although I play it all dead casual.

I have nothing on after eleven o’clock so I spin out my pint of lunch and hop round to the nearest telephone box dead on the stroke of two-thirty, which I consider to be sufficiently far into the afternoon not to appear too eager. Of course, it has been stripped by vandals, and so has the next one. The Post Office is shut because it is early closing day and I am half way to Shermer before I find a box that is operational. I know it is operational because there is a bloke inside dialling numbers he has listed on a piece of paper as long as your arm. I don’t know what he is doing—probably making obscene telephone calls—but it takes him nearly half an hour to do it. By this time I am getting fidgety, to put it mildly, and when he comes out without even saying sorry it is more than I can stand.

“Do you mind if I use your phone?” I ask him.

“Yer what?” is all he can manage.

“I thought you were running a business from in there. How much does it cost to rent it?”

“Get stuffed.”

Now he is talking my language and we have a merry little battle of words before he drives off and I ring up Mrs. C., to find that the number is engaged. This is the last straw and I have asked the operator to check it before I eventually hear a harrassed upper-class voice bark “Cromingham 234.” This would be fun if it was a female voice but, to my surprise, it is nothing of the kind. I ask to speak to Mrs. Carstairs and there is a curt “Hang on a minute” before I hear the bod who answered the telephone shouting out to someone.

“It’s some peasant for you, darling. Hurry up and get rid of him, will you, otherwise I’m going to be late for the plane.”

There is a further interchange and then Mrs. C. comes on, all instant charm. “Hello. Julia Carstairs speaking. Who is that?”

“It’s the peasant from the driving school,” I say haughtily. “You asked me to ring you.”

“Oh, yes. Mr. Lea. Thank you so much. I’m awfully sorry about my husband. He’s got to rush off to Stockholm and he’s a trifle out of sorts. Aren’t you, darling?”

There is another little interchange in which I can hear a voice being raised in the background, and then she returns to me. “He agrees with me. Now, let’s see. Where were we? I expect you know why I rang you. The muse is on me fit to bust at the moment and as soon as I’ve run my grumpy husband to the firm’s airstrip I’d like to get down to work. Are you available at the moment?”

I am still smarting at being called a peasant, but of course I say yes and it is agreed that I will report to the Carstairs residence—”You can’t miss it; it’s the only house in the lane”—at six o’clock, with the promise of a drink and some supper should our session go on long enough.

Ever hopeful, I retire to my lodgings and have a bath, carefully anointing my body in strategic places with some Odour (sic. Ed.) Cologne I keep for the purpose. Thus fortified and having swilled half a cup of Mrs. B.’s Dettol round my chops, I lie down until it is time to go into action.

At six o’clock on the dot my finger is pressed firmly against the nipple-like bell-push of Cavenham Lodge: all white stucco and green shutters with a circular lawn in front cut closer than a guardsman’s chin.

I am trembling with excitement and cold beneath my flared denim jeans and too-tight T-shirt worn under my genuine shaggy sheepskin overcoat and I hope she has got central heating. It occurs to me, as it always does when it is too late to do anything about it, that nothing has been said about posing in the nude. I might be landing myself with a two-hour stint of gazing at a bowl of fruit.

The door springs open and Mrs. C. is revealed, wearing what appears to be judo kit: baggy trousers and a kind of wrap-over waistcoat secured by a sash which matches the one holding back her hair. The action woman bit surprises me as I had been expecting a spot of the long cigarette holders and “Do come in, dahling.”

“Good,” she says. “I’m glad you’re punctual. I’m itching to get at you.” She smiles brightly and leads me through a couple of rooms furnished so that you expect to see John Betjeman standing on the mantelpiece.

“I’m afraid it’s a bit of a shambles where we’re going. Make sure you don’t step on a tube of paint.”

She opens a door in the wall next to what looks like the fiction section of Battersea Public Library and waves a hand at a welter of canvases, trestles and easels which appear in a room slightly smaller than the centre court at Wimbledon. She is not kidding about it being in a mess and it takes me a bit of time to pick out the canvas she intends to work on. This faces a low divan with a few rugs lying on it and is in front of a long mirror which covers one wall of the room.

“The artificial light is a damn nuisance,” she says, fiddling with a few switches. “But if I can sketch in a framework, perhaps you can come back when you have a free afternoon—or morning ideally.”

“I’ll try,” I say. “What do you want me to do?”

This is the sixty-four thousand dollar question and I don’t mind telling you that the sight of the divan has started a few naughty thoughts on a slow bicycle race round my mind.

“Well,” says Mrs. Carstairs slowly, “perhaps I should have told you this before, and I sort of tried to in a way; the particular subject I have in mind requires you to pose in the nude! I didn’t want to mention it right away in case you thought I was some kind of crank.”

When she leans forward to adjust a spotlight I notice that she is not wearing a bra, and I wonder what the rest of her breasts look like. Pretty good, I would reckon.

“That’s all right,” I hear myself saying. “What exactly do you want me to do?” I start to give her the famous Lea slow burn but she is still farting about with the lighting, so I decide to hold it for a couple of minutes.

“I’m going through a classical period at the moment,” she rambles on enthusiastically, “and I have a certain fondness for the Rape of Lucretia.”

Well, we all have our funny little ways, and who am I to point the finger at anybody?

“Oh, yes,” I say, with the easy nonchalance that has made me the toast of the Streatham Ice Rink. “Very nice.”

“Probably something very Freudian about it,” she gushes, “but one can’t help one’s id, can one?”

She is leaving me behind fast, but I smile graciously and start taking my shoes and socks off. She fills me in on the background: how this Roman gent called Tarquin fancied a married bint called Lucretia, who was one of the old-fashioned kind and told him to get stuffed, thus making him decidedly narky to the point where he rammed his nasty up her before she could put down her spaghetti bolognese, thus causing a good deal of ill-feeling all round.

It occurs to me that I am a certainty for the part of Tarquin but that unless the whole thing took place in his imagination, we are going to need a bird. No doubt Mrs. C. has thought of this and I look round hopefully for signs of my fellow model.

“Get on the couch,” says Mrs. C. “I want to make sure I’ve got the lighting right. You needn’t take off your pants yet. Oh, well, it doesn’t matter.”

I stretch out on the couch and she gives me a few instructions whilst sketching away with a piece of charcoal. Apparently satisfied, she pins up a new sheet and smiles at me encouragingly.

“Right, off we go,” she says, and to my amazement she starts to peel off the top part of her robe. “I’m afraid you’re going to have to put up with a rather uncomely Lucretia for a few moments.” Off come the baggy trousers and she is naked except for a tiny pair of panties. And they are on the floor in the time it takes me to write this.

“I daren’t ask any female I know to model in case they think I’m a lesbian,” she goes on, “so I have to do it all myself. That’s why the mirror is such a blessing. Now, let’s see. What shall we try first?”

She is standing beside the divan and her muff is practically tickling my nose. By the cringe, but she is a lovely bird. Ripe and curvy like a basket of pears just before they start attracting the flies.

“Let me lie down while you get on top of me,” she says.

It can’t be bad, can it? I swing my legs over the side of the divan and she snuggles down and tilts back her head.

“Hold my wrists. That’s right. Now bend them back so I look as if I’m being staked out over an anthill. Excellent.”

I imagine she does all this because she likes to live the part in order to get a bit of inspiration and I am about to give her some help when she turns her head to one side and twists away from me.

“Now stick your legs out as far as they will go and lie on top of me. Not bad. Not bad at all.”

She is looking away from me again and I suddenly realise she is studying the shape our bodies make in the mirror. Two more contortions and she leaps off the divan with everything shaking and starts hammering away with the charcoal.

“If you can remember that position it will be a big help,” she yammers. “I’m afraid I’m a bit of a painting-by-numbers expert, no imagination at all. I have to see what I’m doing. Oh dear. I can’t remember how that bit went. We’ll have to do it again.”

And she is over on the divan again with me on top and the faint smell of her perfume playing merry hell with my nostrils and her soft flesh kneading against mine and—

“I can’t go on!” I yelp.

Mrs. C. is surprised. “What’s the matter? Have you got cramp or something?”

“Mrs. Carstairs, you’re a very, very attractive woman. I can’t be as close to you as this without feeling that I want to make love to you—not ‘want’, have got to make love to you. It’s not fair to my nervous system.”

If Mrs. C. can’t feel Percy pressing forward hopefully, like a friendly killer shark, she must be dead from the waist down.

“Well, that is terribly flattering of you. I feel quite overcome. But are you sure? I mean, you’re a young man and I’m old enough to be your mother. Surely you don’t really find me appealing?”

“Put your hands between my legs if you don’t believe me,” I pant. “You’re lovely, gorgeous, fantastic, absobloodylutely marvellous.”

“You’re very naughty,” she says. “I’m not certain that I should encourage you.” What her right hand is doing would seem to contradict this. “Still, I’m incapable of resisting flattery and it might help to relax you, mightn’t it?”

“It might,” I murmur. “Oh, Mrs. Carstairs, it just might.”

“All right,” she says. “In the cause of art I will allow you to make love to me and also”—her fingers wind round the back of my neck and pull my mouth down on to hers—“because I want you to.”