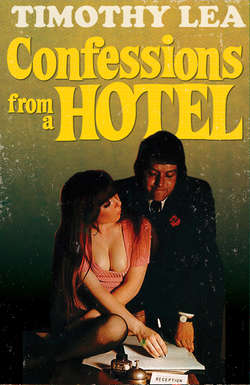

Читать книгу Confessions from a Hotel - Timothy Lea - Страница 4

CHAPTER ONE

ОглавлениеI don’t know how you would handle four weeks on a tramp steamer with a couple of nymphomaniacs, but I was right knackered at the end of it, I can tell you. The second mate was carried off the boat on a stretcher, and he managed to barricade himself in his cabin after the first week. By the cringe, it was a voyage and a half. Now I know what they mean when they say ‘see Naples and die’. Nat and Nan found me skulking in an empty lifeboat the night before we docked and I nearly kicked the bucket with my first glimpse of Mount Vesuvius. Talk about insatiable–I can now, because I looked it up in the dictionary–if those two birds were rabbits it would not have needed myxomatosis to kill off half the male bunny population. I am not unpartial to a bit of the other but–blimey! There is a limit. After the first couple of hours it is becoming more a penance than a penis, if you know what I mean.

Anyway, for the sake of those of you who missed my capers as a Holiday Host with Funfrall Enterprises, I had better explain what I am on about. My period of service on an island off the Costa Brava had come to an end for a number of reasons–not the least of them being that my Dad had burned down the camp. Accidentally, of course. Everything Dad does is an accident, which accounts for how I happen to be about to write this. Anyway, that is another story and I would be the last person to put anybody off their cornflakes by telling it.

My presence on the boat with Nat and Nan–my pen starts shaking uncontrollably every time I write their names–is occasioned by me being left to clear up after the blaze. Once I have sifted all the dentures out of the ashes and paid off the local labour, I am expected to make my way home on a battered tramp steamer calling at every port in the Mediterranean. I would not normally be the first person to start whining about such treatment, were it not for the presence of the deadly duo already alluded to. Also, another lively bird called Carmen who fortunately gets homesick after a couple of days and dives overboard to join a passing fishing boat. Nat and Nan have the same attitude towards sex as those small birds that eat ten times their own weight every day, only in their case, forget small birds and substitute bleeding great vultures. Not that they are unattractive, oh, dear me, no. They are beautiful girls and living tributes to the efficacy of National Health Milk and free dental care. The only trouble is that they do have this disconcerting habit of tearing the trousers off every bloke they meet. And on a few thousand square feet of tramp steamer it gets so it is not worth putting your trousers on again. Your turn is going to come up in another few minutes, buster, so lie back and enjoy it.

Luckily, I have had experience of these girls (I laugh hollowly as I write that) and for the first few days I manage to keep out of the way while the crew run amok. By the end of the first week they are running a mile. Every time the Terrible Twins come round a corner, the sleek smiles slide off their greasy faces faster than blobs of fat off a hot plate. By the end of the second week they are threatening mutiny and by the end of the third week they have twice tried to abandon ship in a lifeboat. One bloke dives overboard the minute we get into the Bay of Naples. How he finds the strength to reach shore, I will never know.

My attempts to avoid being pressed into service–a not altogether happy, but very accurate description of what takes place–founder on my natural desire for food. I am intercepted on a sneaky trip to the galley and from that moment on I am making progress towards a frayed tonk like every other male on board.

By the time we get to Liverpool I never want to see another woman as long as I live–or at least two weeks–and the crew have burned all their pin-ups. The captain has not been seen for four days. Every time anybody taps on the door of his cabin a feeble voice keeps repeating–‘Don’t let them get me. Remember the RNVR.’ The poor basket has obviously gone round the twist.

When we get to Scouseland and can actually see the Liver Building the crew fall on their knees like pilgrims getting their first eyeful of Mecca. There is hardly an Englishman amongst them but they all know that this is where the girls get off. The expression of unspeakable joy on their faces as we go down the gangplank is something I will always remember.

My own feelings are typical of those of any son of Albion returning to the land of his birth–bitter disappointment. When I was on the Isla de Amor I could not wait to feel the native sod under my feet but now as I see some of the native sods in person I wish I was back in the land of the antique plumbing. At least there was sunshine there and I could not understand the newspaper headlines. My tan has been fading since the Bay of Biscay and Mum and Dad and Scraggs Lane seem about as tempting as two weeks in a leper colony.

But that is not my immediate problem. Having seen Nat and Nan closing fast with a group of unsuspecting dockers, I have legged it off in the opposite direction and made my way swiftly to Lime Street station. This being the point of departure for The Smoke, and the bosom of my family. It is mid-morning and British Rail’s excellent inter-city service is decidedly under-patronised. I buy a copy of a book called John Adam–Samurai, which looks as if it has a few juicy moments, and settle down to a couple of hours of peace and quiet. Outside the compartment the sun is breaking through and my spirits begin to lift. Maybe dear old England is not so bad after all.

‘Ah, so there you are! Creeping off without saying goodbye. That wasn’t very kind to your little playmates, was it?’

‘Decidedly unkind, I should say. Not the sort of behaviour Uncle Giles would like, eh Sis?’

Yes, folks; it is Nat and Nan, the girls who gave up the idea of group marriage because they could not find a group large enough. I should mention that the Uncle Giles they refer to is Sir Giles Slattery, Chairman of Funfrall Enterprises, the grave concern that is employing me–and hopefully paying me some much needed moola for my heroic efforts during the last few weeks.

‘After all, we’ve been through,’ says Nat reproachfully.

‘Speak for yourself,’ I snarl. ‘Now for God’s sake leave me alone. You lay one finger on me and I’ll pull the communication cord.’

‘It won’t do any good, darling. The train isn’t moving yet. I’m very disappointed in you, Timmy. I thought we had a chance of liberating you but you’re still very uptight, aren’t you?’ That is another thing about these nutty birds. They believe that if everybody sublimated their aggressions in sexual activity there would be no more wars. That is their excuse, anyway.

‘Take your hand out of my trousers,’ I say. ‘Uptight? After what I’ve had to endure in the last four weeks? I’m slacker than a four-inch nut on a toothpick.’ Nat draws away from me reproachfully and the train jerks into motion.

‘I was hoping we were going to be able to put in a glowing report about you to Uncle Gilesy,’ she says. ‘But if you persist in continuing to be a reactionary slave to bourgeois convention…’ She shakes her head sadly.

‘What do you mean?’ I say nervously.

‘I mean, Timmykins, we may have to tell Nunky that you were very naughty on the boat. That you forced us to cohabit with the crew.’

‘Forced! Those poor bastards are paddling that boat out to sea with their bare hands in order to get away from you.’

‘They did have problems,’ says Nat sadly.

‘They did have. But they don’t any longer. When are you two birds going to wise up to the fact that everybody doesn’t want to get laid all the time?’

‘We could say he confessed to burning down the camp,’ says Nan.

‘Hey, wait a minute!’

‘That’s a good idea. Uncle Gilesy won’t like that, will he?’

‘Timmy will go to prison for arson. Poor Timmy.’

‘You do that and I’ll–’ I rack my brains for something I will do.

‘You’ll do what?’ says Nan. ‘There’s nothing you can tell Uncle Giles about us that he doesn’t know already.’

‘On the other hand, we might suggest some form of bonus as being in order. Nunky is very hot on rewarding loyal staff.’

‘And I’m just very hot,’ says Nat, beginning to pull down the blinds.

‘Just for Auld Lang Syne,’ says Nan, as she starts to undo my shirt buttons. ‘We may never see each other again.’

‘You’re dead right there,’ I say. ‘Once this bleeding thing stops, you’ll need running shoes to keep up with me.’

‘He’s beautiful when he’s mad, isn’t he?’ says Nat.

‘Beautiful. Come on, give us a little kiss.’

Outside the landscape is flashing past at about eighty miles an hour, otherwise I might try to throw myself through the window.

‘Somebody’s going to come,’ I gulp.

‘You never know your luck.’

‘I mean a ticket collector or somebody.’

‘Well, we’ve all got tickets, haven’t we? It just says don’t lean out of the window. And we’re not going to do it hanging out of the window, are we?’

‘I don’t know,’ says Nat thoughtfully. ‘It sounds rather fun. Supposing–’

‘No!’ I scream. ‘Oh my God. What am I going to do?’

‘We know you know the answer to that one,’ soothes Nan. ‘Remember how much fun it was on the beach?’

‘Yes. But there weren’t millions of people wandering about there.’

‘The train is empty, darling.’

‘We could go in one of the loos,’ says Nan, ‘but I hate stand-up quickies and it would be awfully cramping.’

I look at the pictures of some Scottish river on the wall and wish I could be there. The cool water closing over my head–

‘So, you’re going to say something good about me, are you?’ I say. I mean if there is going to be no escape, I might as well get the best deal I can.

‘I hope so, love-bunny,’ murmurs Nat into my half-nibbled ear. ‘Now, let’s see if you’re going to be a good boy.’

Her hand fondles the region of my thigh and finds what it is looking for. ‘Oh yes, I like that.’

‘Me too.’ Nan pops open the buttons of my jeans and slips her hand into the one-way system of my Y-fronts. ‘You shouldn’t wear these,’ she scolds. ‘You should let him breathe.’

‘He seems to be coming up for air now,’ says Nat with interest, as she starts yanking down my pants.

That’s the amazing thing about my John Thomas. It seems to lead an existence totally independent of the rest of me. My brain may be saying run for the hills but my J.T. never seems to hear it. Given the presence of a friendly lady it will lumber fitfully into an upright position and stand there waiting for the best to happen. At moments like this its touching eagerness to please is beyond price.

‘I’m on a bonus, then, am I?’

‘You should be doing this for love, not money,’ says Nat as she helps my jeans over my heels. ‘We really have failed with you, haven’t we?’

‘You’re blackmailing me, so you can’t talk.’

‘I don’t want to talk, angel. I want you to start probing me with your lovely instrument.’

‘You always go first,’ sniffs Nat.

‘No, I don’t.’

‘Yes you do.’

‘Alright. We’ll toss for it. Which ball have I got in my hand?’

‘The left one.’

‘You looked.’

‘I didn’t.’

‘Do you mind!’ I interrupt. ‘I’m not a bloody bumper car, you know.’

‘You give a much smoother ride, don’t you Timmy?–oh look!’

She is referring to the way my J.T. leaps into the air in sympathy when one of the blinds suddenly whips up. I am more engrossed by the faces of the two old ladies who are trotting down the corridor at the time. By the cringe! There are only about half a dozen people on the train and two of them have to be passing at a moment like this. One of them turns away so fast I think her nut is going to twist off. That must be it. A quick trip to the guard and I will be spending the next four months in the chokey for indecent exposure. What a bleeding marvellous way to arrive in the old country. Sir Giles is going to be really chuffed and I can just see the welcome I will get from Mum and Dad–not that their behaviour on the Isla de Amor was anything to write to the Archbishop of Canterbury about.

‘Pull it down!’ I yelp.

‘I’m moving as fast as I can, darling.’

‘I mean the blind!’

‘Look, no panties.’

‘I did notice.’

‘Isn’t Timmy lovely, Nat?’

‘Gollumptious, Nan.’

‘He looks good enough to eat.’

‘You took the words right out of my fevered imagination.’

‘Oh no,’ I gasp as they press me down under the combined weight of their bodies.

‘For God’s sake pull down the blind.’

At last one of them reaches behind her and does as I ask and I must confess that there are worse ways to travel. With those two birds browsing over my flesh I feel like an aniseed ball that has been chucked over the wall of Battersea Dog’s Home. Two hands are better than one–and four! Well, I will let your imagination develop muscles thinking of the merry tricks we get up to in that compartment. Would you believe that one girl could hang from the rack while the other–no, it sounds too far-fetched, doesn’t it? Not the kind of thing that a couple of refined tarts who went to Cheltenham Ladies’ College would get up to. But believe me, mateys, not every bird you meet with calluses on her hand got them from digging her old man’s vegetable patch.

‘Now do it to me, Timmy. Oh, Timmy, Timmy, Timmy. That’s heaven. I’d like to have my own private chuffer train so we could do this all the time.’

Do that and I will pray for a bleeding rail strike every week, I think to myself. I don’t know how I keep pace with them, really I don’t. Maybe it has something to do with the fact that I don’t really fancy them. I mean, they are fantastic birds looks-wise, but there is something so brazen about them that it can never be anything more than a straightforward up and downer. I find it very easy to poke birds when I give my old man his head and let him get on with it–as I have said, he does that most of the time anyway. It is when my mind starts to reckon a bird as well that it begins to foul up my natural impulses. It happened with a bird called Liz I used to go with when I was cleaning windows. I was on the point of marrying her when my poxy brother-in-law Sid introduced her to his nasty and put the kibosh on everything. You know, I was really stretched to get anywhere with that bird. And all because I fancied her too much. Beats anything you read in the Reader’s Digest doesn’t it? Oh well, please yourself.

Anyway, there I am putting up a fantastic fight on the floor of the 10.42 when suddenly the ticket collector lights upon the scene–as they say in the teenage romances. To be honest, I regard him as an angel of mercy because I am on the point of surrender. A man can take so much, but giving it is another matter.

‘What do you think you’re doing?’ he says, all taken aback and disgusted.

The two miserable old crones are craning over his shoulder photographing every inch of flesh for their memory banks.

I feel like telling the bloke that if he does not know what we are doing he would do well to consult one of the many manuals available from reputable bookshops or consider entering a monastery. Either that or find out what his old woman gets up to when she tells him she is going out to tree-felling classes.

But I don’t. Mainly because I am in a position which makes speech rather difficult.

‘We’re screwing, you prick,’ says Nan. ‘Why don’t you get back to your cell and take those two leering slag heaps with you?’

‘You want to watch your tongue, young lady,’ says the stalwart servant of British Rail sternly. I was about to say the same thing, but for a different reason.

‘Throw off your serge and live,’ says Nat whose principles go a bit deeper than Nan’s (eg more than the standard six inches). ‘Liberate yourself! Remove your serf rags! This is the only union worth joining.’

I don’t fancy this joker joining us because he is definitely not the type of person I would invite to any gang bang I was thinking of attending. That is the thing about group sex. It is not the birds I worry about. It is the other blokes. Very nasty!

But luckily I don’t have to worry. Our new friend is definitely not interested in participating.

‘I am going to have to ask you for your names and addresses,’ he says haughtily.

Blimey! Here we go. Hardly an hour in the country and I’m halfway to the nick already.

In the background the old birds are twittering away about how they knew this would happen once the socialists nationalised the railways and it is obvious they have not had such a good time since they poked an Empire Loyalist in the goolies with an umbrella at the Conservative Conference of 1952.

‘If you don’t piss off,’ says Nan, ‘I’ll go and do something unmentionable in the First Class dining car.’

I must say that they are a remarkable couple of birds because they actually get the poor sod to push off on condition that we will give him our addresses when we have got our clothes on. The old birds don’t like this at all but nothing short of instant birching would really satisfy them. I hope I don’t get quite so vicious when I am that age. Still, with a few more like Nat and Nan about I don’t reckon I stand a chance of getting past thirty.

Having a teeny-weeny criminal record for lead-nicking when I was an easily contaminated youth I am not keen to give my name and address to anyone, and have been known to fill in a false monicker on the stubs of raffle tickets. I am therefore relieved that I get my trousers on just as the chuffer pulls into Rugby. Wasting no time I zip up my credentials and grab my suitcase.

‘Well, girls,’ I say. ‘Nice knowing you. Give my regards to Sir Giles. I’ll come round and collect my bonus. Do me a favour and don’t mention Funfrall to Punchy, will you?’

‘You’re not running away?’

‘Living to fight another day. It sounds better.’

‘But Uncle Gilesy will take care of everything. We won’t drop you in it. Honestly we won’t.’

‘I know you mean well, girls, but I also know how things can go wrong. That was how I landed in the nick last time.’

‘You have a criminal record. How super!’

‘Yeah. Longer than Ravel’s Bolero. Now, I must be off.’

The thought of me being Public Enemy Number One obviously turns them on like a fire hose and I have a real job to get out of the door before the train pulls out.

‘We’ll see you, Timmy!’ they holler. ‘Remember! Screw for peace!’

I wish they had not said that because I get a few very old-fashioned glances from the rest of the people on the platform. This is bad enough but worse is to come. On the way to the buffet, I bump into the two old harpies who were having a butcher’s at our love fest. I am surprised that they can recognise my face but there is no doubt that it is firmly emblazened on their memories. They both turn the colour of pillar boxes and grab each other’s arms. Never slow to give total offence, I plunge my hand into my trouser pocket and wait for their eyes to roll across the platform.

‘Have you got a two-penny piece for two pennies?’ I say, eventually withdrawing my pandy, and watch their faces relax into apoplexy. I hop off sharpish before they start any aggro and get the next train with a cup of char and a wad inside me. By the cringe, but it is exotic fare that British Rail dish up for you these days. The bloke in front of me complains because the sultanas in his bun are dead flies. ‘Dey was fresh in today, man,’ says the loyal servant of the Raj who provides for him. I still don’t know if he is referring to the flies.

I get back to Paddington about four o’clock and then it is the last stage of my journey back to Scraggs Lane. I had considered going straight to my penthouse flat in Park Lane but decided that it would break mother’s heart if she did not see me right away. England, home and duty.

I am a bit uneasy about seeing Mum again after her behaviour with that bearded old nut in the Isla de Amor. I mean, this permissive society bit is all right for people of our age, but your own mother! Frankly, I find it disgusting. I mean, I would not set Dad up on a pederast but he is her husband. Gallivanting about in the woods with some naked geezer is not my idea of how my Mum should behave–even if she is on holiday. Of course, I blame the papers myself. All these stupid old berks read about the things young people are supposed to be doing and decide to grab themselves a slice of the action before it is too late.

Dad, I can understand. It was no surprise to find him in that woman’s hut and I was amazed it took him so long to burn the camp down. I would have thought that he would have packed a can of kerosene with his knotted handkerchief, poured it over the first building he came to and woof! The whole bleeding thing over in one quick, simple gesture. But Mum, she was a surprise. I don’t think I will ever get over that.

‘Hello, Timmie love!’

It is my sister Rosie who opens the door which is another surprise. Rosie behaved with the lack of restraint that characterises the normal English rose on holiday and her relationship with the singing wop, one Ricci Volare–and you don’t want more than one, believe me–was hardly what you might call platonic–even if you knew what it meant.

In other words, the two Lea ladies had let the side down something rotten. Like justice they had not only been done but seen to be done.

Rosie is married to my brother-in-law, Sidney Noggett, once my partner in a humble window-cleaning business, now an aspiring and perspiring business tycoon–or maybe it should be typhoon if that means a big wind–with Funfrall Enterprises who you know about.

‘Where’s Mum?’ I ask.

‘Standing on her head against the wall.’

‘She’s what?’

‘She’s taken up yoga.’

‘Oh blimey.’

‘Yes. She wants to find herself. Reveal the complete woman.’

‘I’ve just left two like that. She’s all right, is she?’ I tap my nut.

‘Oh yeah. She says some bloke on the island put her on to it.’

‘Oh my gawd. He hasn’t shown up has he?’

‘No, of course not. What is the matter with you?’

‘Nothing, nothing. It just doesn’t seem like Mum, that’s all.’

‘I think the holiday really did something for her. They say travel broadens the mind, you know.’

‘Yeah. You can say that again. I think I’m going to stay at home for a bit.’

As she talks, Rosie’s eyes begin to glaze over and I reckon she is thinking of Mr Nausea.

‘I thought it was marvellous out there. The heat, the different people you met–’

‘How’s Sid?’ I say hurriedly. I mean, I am not president of his fan club, but I do reckon you have got to stick up for your own flesh and blood. Once Clapham’s answer to Paul Newman starts getting two-timed, then what hope is there for the rest of us? Into the Common Market and–boom! boom!–hordes of blooming dagos leaving wine glass stains all over your old lady. That is not nice, is it? On the evidence of Mum and Rosie you might as well forget about birds and start carving models of the Blackpool Tower out of chicken bones. Of course, it may just have been the weather. Get your average Eyetie or Spaniard over here and his charms probably shrivel up before he has half-filled his hot water bottle.

‘He’s upstairs,’ she says. ‘Recovering.’

‘Recovering?’

From what? I ask myself. I knew he was having a big Thing with this bird on the island, but she looked a very hygienic lady to me. I mean, I cannot believe that she had–

‘You can see him in a minute.’

‘Oh God. What’s he doing here? Why isn’t he lording it back at your country house in Streatham?’

‘We’ve sold it.’

‘Sold it?’

‘Yeah, you can talk to him about that an’ all. Do you want to see Mum?’

‘Naturally.’

I follow Rosie through to the front room–which has not changed, right down to my knee marks on the fireside rug–and there is Mum. I would have had difficulty recognising tier because she is indeed standing on her head with her feet resting against the wall. Her dentures are on the carpet in front of her head like some kind of name plate.

‘Hello Ma,’ I say. ‘It’s me, Timmy. Glad to see you get your knickers from Marks and Sparks. How’s it going then?’

Quite a warm greeting from an only son, locked from his mother’s eyes through five long weeks, I am certain you will agree. I look down at the carpet for signs of tear stains beginning to appear but I am disappointed.

‘Timmy love, never interrupt me when I’m meditating. There are some fish fingers in the fridge.’

And that is all I get. Talk about the younger generation. It is the older generation I am worrying about.

‘I’d better see Sid then, I suppose. What’s the matter with him?’

‘He was shot trying to escape from a prisoner of war camp.’

‘Oh yeah, very funny.’ You have to hand it to Rosie, she is getting a whole new sense of humour. Very satirical.

‘I was shot trying to escape from a prisoner of war camp,’ says Sid when I ask him. ‘It was one of Slat’s ideas. You know he was mad keen on the Blitz and starting holiday camps in deserted tube stations with sirens and muzac by courtesy of World War II?’

‘I remember something about it.’

‘Well, that was just the beginning. When he really thought about it, he came up with Prisoner of War Camps. When you settled up for your holiday you were issued with a rank according to how much you had paid. For two hundred quid you could be C.O. It didn’t make any bloody difference to the food you got but people are crazy about status, aren’t they? Instead of Holiday Hosts you had guards and that cut down on the organisation because they didn’t organise games. They just tried to stop you escaping. Every intake was given a spade and a pair of wire clippers and there was a prize at the end of the fortnight for who got farthest.’

‘How did you get shot?’

‘To get a bit of publicity at the beginning, they got a real German prison camp guard. Well, you know what the Krauts are like. Very thorough. They like to give value for money. I was trying to whip up a bit of enthusiasm for an assault on the electrified fence and he shot me.’

‘He might have killed you!’

‘He said he was doing it for my own good. You see, the fence really was electrified. Slattery reckoned that some dodgy bugger could take advantage and get his two weeks for nothing if you didn’t deincentivise him.’

‘Didn’t what?’

‘It’s a word I learnt on one of Funfrall’s bleeding courses. You can have it. I’m not going to need it any more.’

‘Have you been invalided out?’

‘I’ve resigned with honour.’

‘Why, Sid? You were doing so well.’

‘Breathing is what I do best, Timmo, and I want to make a career of it. My next posting was going to be Kew Gardens.’

‘Kew Gardens!’

‘Yes. They wanted to get Malaysia but Eye Twang Knickers, or whatever his name is, wouldn’t play ball. You see, Timmo, when my number nearly came up they got more applications from people who wanted to be guards than prisoners. It’s understandable when you think about it, you know what I mean? Much more fun machine-gunning people and setting guard dogs on them than it is digging bleeding tunnels. Sir Giles saw that straight away. First of all, he tried to get the Japs to start another Death Railway and promised them cheap labour–but they thought it would be bad for their car exports so in the end he had to settle for the Hot House at Kew. Two bananas and a survival pack is four hundred guineas with cremation at the crematorium of your choice thrown in for nothing. Up on the cat walk with your Hirohito forage cap and a Nippon issue rifle is six hundred guineas or you can have the intermediate, “Jungle Boy” holiday, Dyak blow pipe and a plastic shrunken head for every camper you knock off. Personally, I thought it was going a bit too far. Specially when they said I was going to be umpire. I mean, get a few light ales in that lot and they’d open up on anything. So I said bugger it and handed in my armband.’

‘So you’ve jacked it in, Sid?’

‘Precisely.’

‘Going to leave you a bit short, isn’t it?’

‘Well, I thought of that, didn’t I? I told Sir Giles straight. I said “you can’t go around having your senior executives shot by blood-crazed Krauts and expect to leave a nice taste in everybody’s mouth.”’

‘Right, Sid.’

‘Especially if they are reading about it in the News of the People. I mean, it gets around.’

‘You were approached were you, Sid?’

‘Not exactly approached, Timmy. But I have a few contacts. Know what I mean?’

‘Oh yeah. So Sir Giles paid up, did he?’

‘In a manner of speaking, yes, Timmo. What he really did was to indemnify me against the enormity of the mental and physical suffering I had endured in the course of pursuing my duties in a manner calculated to further enhance the unbesmirched reputation of Funfrall Enterprises.’

‘Blimey Sid, did you say all that?’

‘No, Timmy, my solicitor did. Very good bloke he is and all. I’ll give you an introduction if you ever need one.’

Solicitors? Sidney is really beginning to motor. Another couple of weeks and he’ll be tearing crumpets with the Queen Mother.

‘So you grabbed a nice helping of moola, did you, Sid?’

‘Nosey basket, aren’t you? Yes, if you must know. I did accept a settlement. But not in cash, mind.’

‘What, then?’

‘I bought a hotel.’