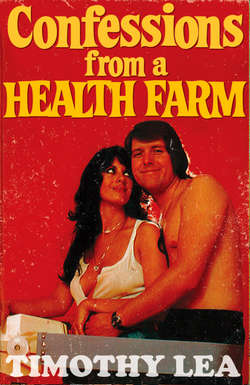

Читать книгу Confessions from a Health Farm - Timothy Lea - Страница 5

CHAPTER 2

Оглавление‘Centre spread of Woman Now!’ says Sid sourly. ‘All right for some, I suppose.’

‘I believe they did a lot of retouching,’ I say.

‘They’d have to, wouldn’t they?’ sneers Sid.

‘On the body hues,’ I say. ‘Come on, Sidney. There’s no need to be like that. Just because I was the first British Mr November in the magazine’s history. I had no idea they were going to use the pictures.’

‘I can’t see why they did it,’ moans Sid, looking me up and down. ‘There must be hundreds of blokes with better physiques than you. Blokes who have whittled themselves down to a tight knot of whipcord muscle. Blokes like me for instance.’

‘I think you may have whittled a bit too far,’ I say. ‘Wanda told me that she daren’t use you in case your dongler got obscured by one of the staple holes.’

Well, I don’t want to boast but I have never seen Sid in such a state before. He is practically begging me to ring up birds he has not seen for ten years to prove that there is nothing wrong with his equipment. Of course, I made the whole thing up so I just sit back and enjoy myself. It goes to show how some blokes are always worried that another bastard has got a beauty that plays Land Of Hope And Glory while it submerges. I say ‘another’ but I reckon that we are all a bit like that. I know I am. The trouble is that you never see the opposition on the rampage, do you? You don’t know what you’re up against – or rather, what the bird you fancy is, was or has been up against. You see a bit of the placid flaccid when you’re in the changing room at the baths but – unless you lead a very exciting private life – it is not often that a male nasty in full flight skims past your peepholes.

I know they say in all those books that size does not matter but if I don’t believe it, what chance have you got of convincing a bird? The books have got to say that, haven’t they? I mean, you can’t spell out the brutal facts too bluntly, can you? Some blokes might decide to knot themselves. It seems obvious to me that a whopperchopper is going to turn a bird on like a good pair of top bollocks do a bloke. Anyway, the point is that Sid is reeling on the ropes and things don’t get any better for him when he sees my fan mail. Really! Some of those letters! Talk about ‘come up and see me sometime’. It is more like ‘drop ’em and cop this!’ No finesse at all.

‘I am slim, blonde and very adventurous and I would like to make love to you until the cows come home.’ Some of the ones from women don’t mince the monosyllables either.

‘Blooming nutcases!’ snorts Sid. ‘Nobody in their right mind would want to be mixed up in anything like that.’

‘Just wait till I’ve finished signing these photos,’ I say. ‘Oh dear, I wish I had a shorter name sometimes.’ I raise my hand to my mouth. ‘Sorry! I shouldn’t have said that.’

‘Said what?’

‘About being short.’

Sid turns scarlet. ‘Will you belt up! There’s nothing wrong with me, I tell you.’

Honestly, it is like taking candy from a kid.

Soon after I have been asked if I will stand as a Liberal candidate, Sid leaps round to Scraggs Lane with his face wreathed in smiles.

‘It’s settled!’ he says. ‘Wanda has come to an arrangement with Sir Henry. She’s been after his seat for a long time.’

This does not come as a complete surprise to me. She did a few funny things when I was with her. Nice but – well – funny.

‘I’m very happy for them,’ I say.

‘Long Hall,’ says Sid gazing into the distance.

‘Was it?’ I say. ‘I suppose she wanted time to be certain.’

‘What are you blathering about!?’ says Sid, unpleasantly. ‘I’m talking about Long Hall, Sir Henry’s country seat. We’re going to turn it into Beauty Manor. Don’t you remember anything you’re told?’

‘It all comes flooding back, now,’ I say. ‘I’ve been so busy with the modelling that I haven’t had time to keep up. By the way, Sid. When do I get paid for all this?’

Sid waves his hands in the air as if trying to dry them quickly.

‘I don’t know. You’ll have to ask Wanda.’

‘But she told me to talk to you about it.’

Sidney closes his eyes. ‘Look, Timmo. We’ve got a lot on our minds at the moment. This health farm thing could be very big. It needs constant attention. You’ll get your money. I’ve never let you down yet, have I?’

‘You’ve never not let me down, Sid. The last time I asked you for some cash you owed me you said “leave it to me, Timmo”. That’s what I’ve been doing all my bleeding life, leaving you money!’

This kind of argument makes less impression on Sid than a caterpillar stamping on reinforced concrete but at least it ensures that he takes me with him and Wanda when they go down to Long Hall.

I am quite partial to the country, once you can get to it, and I have a nice game with Wanda seeing who is the first person to spot a cow – it takes us forty miles, and then it is hanging up in the window of a butchers. Sidney is a rotten sport and will not play. I think he is sulking because he did not think of the idea in the first place – though maybe he is still worrying about the size of his dongler. Acornitis is what I have taken to calling his condition. Every time we drive past an oak tree I shake my head and he goes spare.

‘Here we are,’ says Wanda when we are somewhere on the other side of Henley. ‘Turn right at the gates.’

We sail past a couple of stone lions holding shields in front of their goolies and I soak up the acres of rolling parkland sprinkled with clumps of trees. It is better than any nick or reform school I have ever been to. I never knew you could see places like this if you were not a lunatic or a con. At the end of five hundred tons of gravel is a warm redbrick house with two wings and hundreds of windows – looking at them makes me blooming glad that I’m not still in the window cleaning game. You could perish your scrim on that lot.

‘This isn’t the place, is it?’ I say. ‘Not all of it?’

‘All of it,’ breathes Wanda. ‘Europe’s most modern beauty farm.’

‘You can’t have bought it?’ I say. ‘It must be worth millions.’

‘We’ve set up a company which will run the estate as a beauty farm, restaurant and superior country club. In return for our management expertise and a share of the profits from the enterprise –’

‘And because Sir Henry Baulkit owes us a favour,’ interrupts Sid. ‘We have carte blanche to convert the house to meet the requirements of its new usage.’

I can’t recall what Carte Blanche looks like but I remember the name. She must be one of those posh interior decorators you read about in the dentist’s waiting room.

‘Where is Sir Henry going to live?’ I ask.

‘He has a house in town which he uses when Parliament is sitting. His wife and daughter will be moving into the dower house.’

‘What’s wrong –?’

‘ “Dower” spelt D-O-W-E-R, not D-I-R-E,’ says Sid. ‘Spare me the Abbott and Costello routine.’

‘No need to be so touchy,’ I say. ‘You never learn if you don’t ask.’

‘Can you see that doe?’ says Wanda.

‘You bet I can,’ says Sid. ‘We should make a million out of this little caper.’

‘I was referring to the deer,’ says Wanda coldly.

‘Tch, Sidney!’ I say. ‘You’ve got a little caper on the mind, haven’t you?’

Sidney’s reply to my botanical jibe is unnecessarily coarse and hardly suitable for repetition in a book of this kind. I am glad when we arrive at the pillared front door.

‘Blimey!’ I say. ‘Take a gander at that bird. It looks like the hat Aunty Edna wore at Uncle Albert’s funeral.’ I remember the item well because there was a lot of talk about it at the time in family circles. It was also considered that the choice of scarlet stockings was inconsistent with the impression of a woman trembling on the brink of physical collapse over the loss of a dearly loved one. No one was very surprised when she married the coal man two months later. ‘She always had dirty finger nails,’ said Gran, significantly.

‘That’s a peacock,’ says Sid, following my gaze. ‘Blimey. Haven’t you ever been to Battersea Park?’

‘Some bugger nicked them two days before I went,’ I say. It is funny, but now that Sid reminds me, I seem to recall that the keeper was reported to have seen a coloured bloke climbing out of the aviary. I suppose it could have been a coal man …

‘Don’t look for a door bell,’ says Sid scornfully. ‘Houses like this don’t have them. Fold your mitt round that piece of wire and give it a pull.’

I do as I am told and we are lucky to avoid serious injury when the lightning conductor comes hurtling down and misses us by inches.

‘It’s going to need a few bob spent on it,’ says Sid, wisely.

‘What do you think of the weathercock?’ says Wanda.

‘Not bad for the time of year,’ says Sidney. Sometimes I don’t know if he is trying to be funny. Before I have the chance to find out the front door opens. An elderly geezer wearing a stained tail coat and a haughty expression looks down his hooter at us.

‘We have all the clothes pegs we need,’ he says coldly and tries to close the door.

‘Hold on a minute, Roughage,’ says Sid. ‘It’s me. Remember? I came round with Sir Henry.’

‘I don’t even remember the two of you being unconscious,’ says the ancient retainer. I can sense that with two such ace gagsmiths as him and Sid together sparks are surely going to fly.

‘Roughage! Surely you remember me? I’m going to convert the house into a spa.’

‘You’re wasting your time. There’s a new Tesco just down the road.’

‘Stop trying to close the door on my foot! Miss Zonker and I have a perfect right to be here.’

‘Does she charm warts?’ says Roughage, showing faint signs of interest.

‘She charms anything,’ I say gallantly.

‘Shall I show him my credentials?’ says Wanda.

‘Don’t overdo it,’ says Sid. ‘You can have too much of a good thing.’

‘What about fortune telling?’ says Lizard Chops. ‘Her ladyship has been powerfully attached to the crystal ball in her time.’

‘Quality rather than quantity, eh?’ says Sid, sounding comforted. ‘I don’t know where you get the impression that we’re gypsies.’

‘And don’t park your caravans up by the pigs,’ says Roughage, who seems to be a bit hard of hearing.

‘You mean, because of the smell?’ says Sid.

‘That’s right. Two of the pigs passed out last time. We had to give them mouth to mouth resuscitation.’

‘How horrible!’ says Wanda.

‘It was. Both of them died.’ Roughage scratches his head thoughtfully. ‘Maybe there’s something in those toothpaste advertisements.’

‘Come, come, my good man,’ says Sid. ‘We can’t stand here talking all day. Miss Zonker and I have work to do.’

‘And so have I,’ says the grey-haired Roughage. ‘I’m supposed to be helping her ladyship move into the dower house. She’s very put out by the way things have gone.’

‘I’m certain Sir Henry has her interests at heart,’ says Sid. ‘Timothy, why don’t you give Roughage a hand while I help Miss Zonker decide where to put her equipment?’ He runs his horny hand up the small of her back and I imagine the evil little thoughts that are pelting through his mind – even an evil little thought likes to keep moving in a place like that.

‘Of course,’ I say. ‘Where shall we meet?’

‘Down by the lake,’ says Sid. ‘There’s a gazebo at the far end.’

‘He won’t still be there when I’ve finished, will he?’ I ask.

‘A gazebo is a kind of summer house,’ says Sid, as if pronouncing the words causes him pain. ‘You’ll have to become a lot more araldite if you want to be a success at Beauty Manor.’

‘You mean “erudite”, Sid,’ I tell him. ‘Araldite is something you use for sticking parts together.’

‘I’ve never found that necessary, myself,’ says the little Lithuanian knocker factory.

‘Whatever I mean, you’ve got to smarten yourself up,’ says Sid. ‘Everything here has got to be done with tremendous couth.’ He does not wait for a reply but scampers off hand in hand with Wanda. Roughage clears his throat and looks round as if for somewhere to spit.

‘I don’t hold with it myself,’ he says. In the weeks to come this is a phrase that falls frequently from his withered lips.

‘I suppose we’d better get on with it,’ I say.

Roughage looks me up and down with contempt. ‘No need to rupture yourself,’ he says. ‘We’ve got all day.’

I am about to point out that I have considerably less than all day when the ancient retainer beckons me into a room bigger than anything I have ever seen outside the labour exchange. There are pictures painted all over the walls, and the ceiling looks like the sky with a load of fat tarts lying on clouds and being touched up by cherubs. Quite saucy it is, really.

‘You don’t need a telly, do you?’ I say cheerfully.

Roughage looks sourer than a furry yoghurt. ‘Them Baulkits wouldn’t give you the time of day,’ he says. ‘They take the batteries for the cook’s transistor out of her wages.’ Before I can reply he walks over to a long polished table and picks up a cut glass decanter full of booze. Removing the stopper he takes a long swig. This is not easy because the mouth of the decanter is square and I can see why the front of Roughage’s suit looks as if it has been used for pressing out the lumps in a vat of treacle.

‘Elevenses,’ he says with a loud hiccup. ‘One of the perks of the job.’ He opens the lid of a silver cigarette box and slips his hand inside. ‘OW!’

When he has stopped jumping about I help him remove the mouse trap from his fingers and he sticks his digits in his cakehole. It is not a course of action I would have followed myself, but then, I never did reckon that mice were as clean as a bar of Lifebuoy.

‘It’s no wonder they can’t get the servants these days,’ he says. ‘Who would put up with that kind of treatment when they could be making more money as a toast master?’

‘You’d get fed up with making toast all the time,’ I say. ‘Anyway, the machines are taking over.’

Roughage gives me a funny look and for a moment, I think that he is going to say something. Then he takes another swig from the decanter.

‘What is it?’ I say.

Roughage smacks his lips together for a couple of moments and then an expression of extreme distaste begins to dawn on his face. ‘Syrup of figs!’ he shouts and pushes past me into the hall.

What a funny set-up, I think to myself. His taste buds must be a bit on the dicky side if he can make a mistake like that. I always thought that butlers were supposed to know their way round a bottle of plonk.

It is also clear to me that relations between employer and staff are not going to teach Ted Heath any lessons. Roughage seems to awaken feelings of distrust in the Baulkits and I am not entirely surprised. I would not leave him alone with my money box and a bent hairpin.

‘What are you doing here?’ I whip round to see a bird of about forty peering at me from the doorway. She is wearing a lot of makeup and a suspicious expression. Although a bit on the thin side she is definitely not undesirable. She plucks anxiously at a string of pearls and feeds a second helping of upper class accent into my lugholes.

‘You’re not a sex maniac, are you?’

‘No,’ I say, taken aback.

‘Oh.’ She sounds disappointed. Knickers! I always have to go and say the wrong thing. ‘Then what are you doing here?’

‘I’m helping your butler with the move,’ I say. ‘Are you Lady Baulkit?’

‘For my sins,’ says the bird, fluttering her eyelashes at me. ‘That’s the best way of marrying into the aristocracy, you know. When I met Henry I was wed to another.’

I nod understandingly. Dad has frequently pointed out to me that the upper classes get away with murder when it comes to sack jumping and make hideous mockery of the nuptial couch. He is dead jealous, of course.

‘He was a retired Lieutenant-Colonel in the Pay Corps and we lived in Scotland. I met Henry when he came up for the shooting.’

‘Grouse?’ I say.

‘No, the village post mistress. The role of mistress was one she filled for more than just the GPO. Her husband was a very jealous man. Henry was cutting his teeth on the Aberdeen Press and Journal at the time. He always had a penchant for journalism.’

‘I expect it came in very handy,’ I say, wondering what she is on about. These upper class bints are inclined to be gluttons for the rabbit. I remember from my window cleaning days how they would always be bending your lugholes over a muffin and a cup of jasmine tea.

‘It was love at first sight,’ she says. ‘Rude men have always appealed to me. In those days he would pull his pyjamas on over his riding boots. It took me six months of marriage to stop him wearing spurs in bed.’

I nod my head sympathetically. Fascinating how the other half lives, isn’t it? Oh well. Please yourself.

‘Does any of this stuff have to be moved?’ I say, looking round the room.

‘No. If you touched anything it would collapse in a cloud of dust. It’s upstairs that I need some help.’ She tries to flutter her eyelashes but they carry so much mascara that one set sticks together and falls on the floor. I gaze out of the French windows like a gent while she repairs the damage.

‘Are you from the village?’ she says.

‘No. I’m employed by Inches Limited,’ I say. ‘You’ve probably met my brother-in-law; Sidney Noggett?’

‘Does he have very cold hands?’ she says.

‘I don’t know,’ I say. ‘I don’t think anyone in the family has ever mentioned it.’

‘They’re probably used to it,’ she says. ‘You do get used to things like that. I remember my first husband – just.’

‘When you were living in Scotland?’ I say, trying to show interest.

‘No. Nairobi. Kenneth was my second husband. I met him in Kenya.’

‘That’s why you pronounce it like that, is it?’ I say, keeping the conversation bubbling along.

‘No,’ she says, coldly. ‘I have a friend at the BBC who explained it to me. Anyway, what I was trying to say was that he had very cold hands.’

I am not quite certain whether she means Kenneth, the first husband or the bloke in the BBC. On reflection, it does not seem to matter very much.

‘Where is Roughage?’ says her ladyship.

‘I think he was taken a bit short,’ I say, trying to put as good a face on it as I can.

Lady Baulkit picks up the decanter he was glugging from and holds it up to the light. ‘I’m not surprised,’ she says. ‘He’s been at the syrup of figs. Ghastly old man. I don’t know why Henry keeps him on. Sentiment, I suppose. He’s been attached to the family so long we call him verruca.’

I nod understandingly and come to the conclusion that Lady Baulkit has a very nice set of pins. I have never been so close to a titled bint before and the experience sends a nervous tremour through my action man kit. Of course, it is too much to hope for that a spot of in and out might be on the cards but the thought alone is enough to send a warm glow skipping the length of my love portion. You only have to sound all your aitches to make me score heavily on the humble meter.

‘Of course, it’s not easy for a woman.’ Lady Baulkit’s voice trembles and she looks deep into my mind – about six inches deep. ‘The responsibility of the house and servants. Henry is away most of the time.’ She stretches out a hand and touches my wrist. ‘A woman has needs.’

‘Too true,’ I gulp. ‘Well, I – er suppose we’d better go upstairs.’ I mean, of course, to help with moving her things. I hope she does not misunderstand me. I step towards the door.

‘Don’t go that way. We’ll take a short cut.’ Lady B glides to the fireplace and grabs one of the carved cherubs by his John Thomas. Ouch! – it makes me wince to see her do it. A flick of the wrist and – blimey! A panel beside the fireplace slides open and I can see a flight of stairs.

‘In the old days, this is what you had to do to get into the priest’s hole,’ says her ladyship.

‘Really,’ I say. It is not a subject I feel keen to pursue. I believe that they had a lot of funny habits in those days.

‘There’s a network of secret passages connecting most of the rooms in the house,’ says Lady B. ‘Charles II used to stay here a lot with his lady friends.’

‘Very nice, too,’ I say. ‘Do we need a torch?’

‘Just take my hand.’ Lady B grabs my mitt before you can say ‘Kismet’.

‘Blimey! It’s dark, isn’t it? Are these stairs safe?’ The panel has slid shut behind us and my guide laughs lightly.

‘That depends who you’re with,’ she says.

I don’t want to jump to any hasty conclusions but a number of things that she has said and done suggest that she may be a bit on the fruity side – like a ton and a half of sultanas, for instance.

Now that we are in what you might call an enclosed space, her perfume begins to run riot through my conk and the sound of her silk dress swishing in the darkness awakens what my old headmaster used to call unhealthy thoughts.

‘It’s rather fascinating,’ breathes Lady B. ‘There’s a number of peepholes along here. You can keep an eye on the staff if you have a mind to.’ She pauses so that I nearly bump into her and pulls something aside so that a crack of light appears. ‘Look,’ she says after a pause. ‘Cook is rolling out the pastry.’

I apply my eye to the crack and – blimey! Cook is indeed rolling out the pastry – with the help of Roughage. He has made a remarkable recovery and is performing with no little agility for a man of advanced years. Another dollop of dough drops onto the floor and he kicks it savagely under the table. I must make a point of steering clear of the flap jacks – especially the ones with a seam.

‘The staff seem to get on well with each other,’ I say, deciding that some comment is probably expected of me.

‘Yes. I’m surprised that cook still has it in her.’

‘She doesn’t any more,’ I say, removing my eye from the crack. Short but sweet is probably the best that can be said for Roughage’s doughnut filler.

‘You have to be so careful with your menials, these days,’ murmurs Lady B. ‘Rub them up the wrong way and you’ve got a nasty problem on your hands.’

I feel myself blush scarlet in the darkness. I know we live in emancipated times but I never like to hear a woman talking like that. It’s not nice, is it?

‘This is the Seymour Room along here,’ she says. ‘One of the largest four posters in the country.’ She applies one of her mince pies to another peephole and gives a sharp exclamation of disgust. ‘Well, really! They might have taken the counterpane off first.’

I try to get a shufti but she shrugs me aside and flicks open another peephole. ‘Twin-viewing,’ she says. ‘It’s no fun going to a show by yourself, is it?’

I grunt my thanks and we settle down to take an independent view of the proceedings. My first glance explains to me why they call it the Seymour Room. I have not seen more in a long time. This bird is lying on the bed absolutely starkers and there is some bloke zooming over her contours like a Flymo Lawnmower. I can’t see his face, and I don’t reckon she can, the way he is heading. It is definitely for mature adults and I feel Lady B stiffen in the darkness. She is not the only thing. Percy gets the message that good times are rolling and starts trying to clamber over the front of my Y-fronts like he is on a Royal Marine Commando assault course.

‘Who are they?’ breathes Lady B. ‘It’s bad enough when the house is open to the public without complete strangers –’ She stops just as Sidney comes up for air.

‘You recognise him, do you?’ I say.

‘The one with the cold hands! What’s he doing here?’

‘He’s practising giving the kiss of life to a bird who has got a coal scuttle wedged over her nut,’ I say.

‘Don’t be facetious! I mean, why is he here at all?’

‘He’s siting Miss Zonker’s equipment,’ I say. ‘You must know all about Inches Limited and Beauty Manor. Your husband is one of the directors.’

‘He never tells me anything,’ she says. ‘Our marriage is a marriage in name alone. I’m expected to vacate my home so that perfect strangers can fornicate in it while he cavorts in town. I ask you: is that fair?’

‘Not bad,’ I say, concentrating on what I can see through the keyhole.

‘I’ve mouthed a few imprecations in my time, I can tell you.’ She doesn’t mind what she says, does she? I reckoned she might be a nunga nibbler when I first saw her. You can tell, you know. It’s something about the way her eyes shine.

‘Smashing,’ I say. Now Wanda has got on top of Sid and is pinning him down with her arms while she bashes out the theme of Ravel’s Bolero on his magic poundabout. It is not exactly the bedrock of children’s television but it is absorbing viewing.

Lady B obviously agrees with me. ‘You can imagine how I feel watching that,’ she says. I don’t have to imagine for long because her hand steals out and draws one of mine to her. She seems to be trembling.

‘You feel very nice,’ I say.

A fine haze of dust is now falling from the top of the four poster bed and the whole structure is vibrating like a tin shit-house in a hurricane. A grand stand finish is clearly on the cards and one of the pictures on the wall at the end of the room crashes to the floor.

Lady B. groans. ‘That’s a Van Dyck.’

‘He’s very versatile, isn’t he?’ I say. ‘Though I didn’t think much of his English accent in Mary Poppins.’

Further discussion on matters artistic is denied us because the canopy over the four poster bed collapses in a great cloud of dust and rat shit.

I am not sorry that the sight of Sid on the job has been banished from my eyes because it was getting a bit heavy. Once he turns purple and his eyes glaze over I would rather watch a good horror movie. It is like those Swedish films when they start all that thrashing and moaning. It quite puts me off my cornflakes.

‘My God. That’s priceless!’ yelps Lady B.

‘It is a bit funny, isn’t it?’ I say. ‘Especially with his legs sticking out of the end.’

‘I meant – oh! It’s too awful!’ Her voice is almost a shriek and it is a good job that Sid and Wanda are in a somewhat muffled condition. It would be most unfortunate if their concentration was shattered.

‘Supposing we can’t get it up?’

She is a very funny woman, this one. There is no doubt about it. Not only forward but pessimistic with it. I think maybe that her mind has become a bit unhinged due to lack of oggins. Because she can’t get it she has to try and persuade herself that it wouldn’t work anyway. Maybe this is a case for SUPERDICK – yes! I can see it all. Somewhere behind the wainscotting of ancient Long Hall, attractive Lady Baulkit yearns for a spot of in and out like what she can see being dished out in the appropriately named Seymour room. Beside her, simple unaffected Timothy Lea cowers in the darkness and feels the change in his pockets – the change that will turn him into: SUPERDICK!