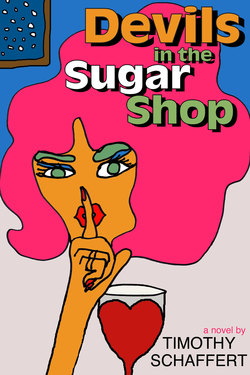

Читать книгу Devils in the Sugar Shop - Timothy Schaffert - Страница 6

Ashley, Deedee & Viv

ОглавлениеAshley Allyson, the failed erotic novelist, stood in Mermaids Singing, Used & Rare, with an armful of pink, freckled lilies, the stems wrapped in tissue, bought from the corner florist in the Old Market. Ashley remembered her mother calling that breed of lily a naked lady because its many leaves dropped off as it bloomed.

Despite the falling temperatures outside, and despite wearing only her husband’s elbow-patch tweed jacket over her nearly threadbare Concrete Blonde concert T-shirt, Ashley felt faint from the heat of the bookstore. But she couldn’t bring herself to leave just yet.

For weeks and weeks, possibly months and months, a copy of Ashley’s first novel had sat on a shelf in the fiction section of Mermaids Singing, unsold even with the low, low price of $3.95 penciled into the upper-right corner of the title page. Now Ashley saw that the book was finally, blessedly gone.

Whenever she was in the store and no one was looking, Ashley would take the novel down from the shelf. Just an inch or two too petite, she’d have to step up on the bottom shelf of the bookcase, reach high, and crook her finger into the bottom of the spine to tug the book from where it was stuck in between the humid magic of Isabel Allende and Jorge Amado. She would dust off its dust jacket with her sleeve, be charmed again by the Alex Katz painting reproduced on it. She would slip off the jacket and run her thumb over the initials of her name embossed in the cloth of the cover, and read again “A Note About the Type” on the last page (“This book was set in Mrs. Pickering Neoclassical, a typeface based on an alphabet created by a children’s book author in 1848 . . .”). Overlooking all the weaknesses of the novel itself, Ashley could still become mesmerized by the book’s physical beauty, right down to the elegant stitching of its pages to the binding, all in pink thread.

Though it was early February, when Omaha stayed gray, with muddy, sooty snow melting and refreezing in the gutters, Ashley felt uplifted. Someone, against all possible odds, had bought her abandoned little book. And maybe this someone would see the novel’s qualities, find its heart, and fall in love with its cast of fragile creatures.

Feeling generous, Ashley stepped over to browse the shop’s selection of rare books. She decided she’d buy her husband a pricey Valentine’s gift, the signed copy of The Moviegoer, perhaps, or the Peter Max Paper Airplane Book, its pages meant to be torn out and folded, with trippy statements of love and peace across Popsicle-colored wings.

But as she ran her finger along the front of the cabinet, she became sad at the possibility of this sentimental gesture losing its every bit of romance in the chill of their apartment. Something was wrong in her marriage, and that something weighted every exchange and pleasantry and informed every sharp tone. After nineteen years of raising a family together, she and Troy had fallen out of touch in their own home, lost among their own things.

Ashley and Troy had married at the very beginning of their adult lives, so everything they owned belonged completely to the both of them. If their marriage ever ended, they’d have to divide down an impossible middle, determining whether something was somehow more his than hers, or more hers than his. This book she might buy, for example: it would be Troy’s gift, but it was Ashley’s thought that counted, wasn’t it? The book would represent this spontaneous Saturday-morning side trip into Mermaids Singing, these lilies, the snow falling lightly outside, her enthusiasm that turned to melancholy.

If divorce loomed, they’d have to decide who got the circa-1950s Frank Lloyd Wright cocktail table they’d bought while antiquing in Madison County on a romantic weekend touring the historic bridges, or the French poster for Annie Hall that had hung on the bedroom door of their first apartment, or the clear broken horn from a crystal unicorn that their daughter, Peyton, had used as a stage prop in her high school’s production of The Glass Menagerie, a tiny spiraled piece of glass she’d presented to her father as he’d handed a bouquet of blue roses up to her from the orchestra pit during the curtain call and the standing ovation. Such a sweet moment.

The grandfather clock in the corner of the bookstore chimed eleven times with effort, its squeaky gears and workings about to give. Ashley had to run. She taught a Saturday-afternoon writing class, and later that evening she was hosting a girls-only shindig, which was the reason she’d ventured out at all, for flowers, a peek of spring, this miserable icy morning.

As Ashley turned to leave Mermaids Singing, she saw the bargain bin, a wooden wine crate full of books, “The Last Ditch, $1” painted on its side. That long-unsold copy of her novel, its dust jacket now with a new, painful little rip from clumsy handling, sat at the top of the pile.

The bookstore was owned by identical twentysomething twins named Peach and Plum, and Peach took Ashley’s writing class. Ashley sighed, glancing around the empty store autumnally lit by haphazardly placed lamps with dusty shades. A shadow slipped around a corner, and the dry pages of an antique pinup-girl calendar rustled in the shadow’s wake. Perhaps Ashley had once been too harsh to Peach in her criticisms. Her students were often so sensitive about their work.

Deedee Millwood lit another cigarette off the coal of the duty-free Virginia Slim at her lips. Her daughter, Naomi, sat at her side, picking the cheese off a limp slice of airport pizza and mock-coughing melodramatically. Naomi, at sixteen, felt the need to pretend she didn’t smoke, but Deedee knew she did. She could frequently smell the smoke in Naomi’s hair and on the urchin-like, thrift-shop schmattes she insisted on wearing. But Deedee couldn’t scold—her ex-husband, Naomi’s father, would just turn the scolding to his advantage, would probably buy Naomi cartons of unfiltered Camels to overcompensate, would install a hookah pipe and a humidor in her weekend bedroom at his apartment.

Just the thought of Zeke’s competitiveness, his spoiling of their daughter, made Deedee swoon. She wasn’t still in love with Zeke, she was back in love with Zeke, and she found falling back in love far more thrilling than when she’d been simply still in love, back when the divorce was raw and sharp-edged, rendering her hopes pathetic and desperate. Clinging to love was sad; reviving an old love was romantic. Now if she could only convince Zeke to fall back in love too.

Deedee tucked a few skinny, beaded, rat-tail braids behind her ear. She had several such braids, all having been beaded on the stormy beach of the island in the Bahamas from which she and Naomi were returning. Though the beach had been mostly empty the afternoon before because of the rain and the wind, some of the locals had still set up shop to do braids, sell T-shirts and tiedyed scarves, and mix Coco Locos, the rum drinks they served in real coconuts with fluorescent twisty straws stuck in.

Deedee had been making a small fortune selling “marital aids” throughout Omaha and the rural communities of Nebraska, Iowa, and South Dakota. She had been named salesperson of the year for the Midwest region of Sugar Shop, Inc., earning her a trip for two to Paradise Island in the Bahamas.

Women throughout the Bible Belt, put off by the matronly domesticity of Tupperware and Pampered Chef, hosted the Sugar Shop parties in their living rooms, their neighbors bringing covered dishes and Jell-O rings, to sit for innocent, bubbly presentations of waterproof sex toys and fruit-flavored lubricants and novelty condoms. Sugar Shop, Inc. prided itself on its accessibility. In its brochures it spoke of sex in a coy and flowery language that nonetheless could provoke a roomful of respectable ladies—ministers’ wives, kindergarten teachers—to raucous states of impoliteness. The party’s hostess in a tiny Nebraska town such as Ong or Wahoo or Friend might mix a pitcher of Cosmos or pots of Irish coffee with whipped cream, and though the drinks were often only lightly spiked, the women felt free to unzip their lips and offer indiscretions. They’d let slip the size of their husbands’ schlongs, or they’d all commiserate over their husbands’ laziness or lack of innovation between the sheets.

And through it all, Deedee would maintain her composure—she wouldn’t act prudish, certainly, but she’d offer little more than a wink and a smile as she pulled from her satchel things she introduced as “the Lemon Pucker” or “the Cocoa Puff” or “the Tickled Pink.”

And that was why she was such a success, Deedee believed. By not indulging in the frenzied atmosphere of lighthearted vulgarity, she allowed the women to feel they’d remained unsullied by the Sugar Shop. Deedee kept the parties from descending into bacchanals that might otherwise throb in the women’s heads the next morning like an afternoon infidelity or a late-night online chat with a stranger. No matter what the women confessed while under the influence of an appletini, no matter what product they skittered back to the bathroom to sample, they could leave the party feeling that a check written out to the Sugar Shop was no more sordid than one written to the pharmacist for a refill on birth control or to the highway steakhouse for a dinner that included one too many glasses of Chianti.

At parties, Deedee tiptoed around the discussion of private parts. The honeybee on the lip of the lily, she’d say instead. The sunset on the stormy sea. The devil’s stogie. The candied violet in your heart-shaped box. She was never lewd; hell, she wasn’t even frank.

None of it embarrassed Deedee. She had never been a success before—she still had boxes of unsold Mary Kay cosmetics rotting in her garage, the mascara gone to clumps and the blush dried up. In her closet hung expensive executive suits worn too little to have ever worn out, and she had a desk drawer full of name tags, “Deedee Millwood” echoing in a variety of fonts, mocking the fact that she’d never before, anywhere, been a perfect fit.

“Are you ever offended by what I do for a living, Naomi?” Deedee asked her daughter.

“No, but I’m offended that you’d think that,” Naomi said. “Do you think I’m so judgmental? It really wouldn’t hurt you to get to know me sometime. I’m sorry, have we been introduced?” Naomi reached out, inviting a sarcastic handshake. “I’ve been your daughter for sixteen years. It’s nice to finally meet you. I’ve heard so much . . .”

“Okay, okay,” Deedee said. She slapped at Naomi’s hand.

“Let’s scoot,” Naomi said, tapping the face of Deedee’s watch, which she’d left set to Omaha time throughout the entire vacation. Eleven A.M., time to board their connecting flight back home.

“We’ll scoot in a sec,” Deedee said. She pointed at her half-smoked cigarette and refused to move. Upon the return to Omaha, she’d be back at work, leading a Sugar Shop party at the Old Market apartment of her best friend, Ashley.

As she continued to smoke, the look of the dilapidated glassed-in smoking lounge, with its awful orange furnishings riddled with burn holes, perked up, became sickly appealing. She suddenly delighted in being cordoned off with these other addicts. The air in the room was a deadly haze of spent tobacco, and Deedee couldn’t bring herself to leave. She grabbed Naomi’s arm and gripped hard, not letting her stand. Despite her fine life, with its brand-new townhouse, roadster convertible, and weekly spa treatments, this return from vacation struck Deedee with a deep panic she didn’t quite understand.

Vivienne Dailey opened that day’s mail when it arrived at her studio: one sole envelope, her name in the block letters of anonymity, the latest from her so-called stalker.

At the end of the year, she’d been featured in an article titled “Flirty and Under Forty: Ten Omaha Beauties to Watch” in a local magazine that chronicled such things. Within days of the magazine hitting the newsstands, Viv and the nine other beauties had begun receiving the disturbing materials. The Flirt, as he was speedily dubbed by the Omaha World-Herald, was sending each woman depraved collages, scissoring the women’s heads and hands and feet from the magazine photographs and rubber-cementing them over the heads and hands and feet of the models in gritty, truck-stop, damn-near-gynecological porno mags. The Channel 7 news had shown one of these collages on TV: Viv’s smiling, severed head pasted onto the body of a busty woman wearing only a navel ring, the model’s nipples and privates pixilated by the TV station’s censors. The model’s hands had been replaced with Viv’s French manicure, her feet with Viv’s Vera Wangs.

The Flirt had been at it for twenty-five days and twenty-five collages, most of which Viv now kept taped to the exposed brick of the back room of her artist’s studio in the Old Market. She’d been preparing for the drawing class she’d be teaching later that afternoon, but she stopped to study the collages, not one of which featured a black woman’s body. Viv’s head with its Medusa-like nest of black dreads with blond streaks, her brown hands and brown feet in black shoes, were all glued to lily-white extremities.

Viv scratched the head of Yvonne, her docile Yorkie. The tiny dust mop of a thing was named after a Great Dane of the 1960s, the pet that had accompanied the woman who’d shot bullets into Andy Warhol’s portrait of Marilyn Monroe.

“You go through life,” Viv muttered to Yvonne as she eyed her own head taped to the body of a woman whose pierced nipple was being licked by a man with a mustache, “thinking you’ve pretty much seen it all.” You think that maybe you’re even a little bit on the edge of things, she thought, a little daring. Then you get a peek of true underbelly, and you realize just how innocent you are.

Viv didn’t tack up the one that had just arrived, or the ones from Thursday and Friday—she was experimenting with the pictures. She’d cut the women into pieces, dismembering the models limb by limb, joint by joint. She’d also cut up the Sugar Shop catalog her friend Ashley had sent along with the invitation for the party that night. The top of Viv’s desk was littered with clippings of dildos and vibrators, see-through undies and push-up bras, along with arms and legs, knees and elbows, necks and nipples. Viv wasn’t sure yet what to do with all the pieces. She toyed with the idea of making adult paper dolls and had even cut out a string of zaftig ladies from some folded-up black construction paper, black dolls that you could dress up in negligees and strap-ons, or in a white girl’s arms and legs.

Her art tended to make people nervous. Her mother had even speculated that she’d brought the stalker upon herself, that she provoked people into perversity. “You should do more of those pretty shoes,” Viv’s mother had told her. For a time, Viv had made lithos of the designer shoes she’d splurged on one summer to console herself after a wicked breakup—python slingbacks, calf-trimmed pumps, fur clogs, kitten-heeled patent leathers. She’d had prints of a pair of Ferragamos and some Bettye Mullers and some pink leopard-print Claudia Ciutis in shows around town and had shown a few pieces in New York and one in Chicago. But any of her quasi-political work, like her paintings of black icons reconceived as white people—a strawberry-blond Butterfly McQueen in Gone with the Wind, the blue-eyed family from The Cosby Show, a pale, pink-breasted Josephine Baker in banana skirt—seemed only to make her patrons cranky.

Viv poured some Beaujolais into her coffee mug, though it was only eleven in the morning, and contemplated how she might incorporate the stalker’s collages into a dirty pop-up book—turn a page and pop, there’s Viv’s head with her goofy, girly smirk and wink atop a body with a long-stemmed black rose tattooed up one milky thigh; turn another page, and pop, a lady spread-eagled with a bird-feather boa around her arms; then, pop, a woman shaved bald down below; pop, some crotchless panties, pop, bejeweled pasties pasted on gigantically enhanced breasts, pop, a lady with a pet dog, a mottled pear, a box of chocolates, pop, pop, pop, pop, pop.