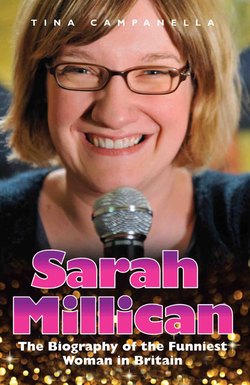

Читать книгу Sarah Millican - The Biography Of The Funniest Woman In Britain - Tina Campanella - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Early Years

Оглавление‘I don’t think a lot of the girls I was at school with would have thought for a second that I would be doing this for a living. I see it as a regeneration – you know, like in Doctor Who – I am a version of that person, but it’s a totally different version.’

Sarah Millican has come a very long way since she first decided to try her hand at stand-up comedy, aged 29. While other comics spend decades performing to small crowds in pubs and clubs, it has taken Sarah just eight whirlwind years to be crowned Britain’s new first lady of funnies.

Sarah’s brand of comedy could easily be described as defiant. The Geordie comic has certainly had to fight her way through life – elbows out – in order to rise to the top of the UK’s crowded list of comedy talent.

But it was her challenging early years that first put her on the path to becoming the queen of filthy humour that she is today. Instead of accepting her lot, she channelled even her toughest breaks into a special brand of Millican fuel – which would quickly ignite her stellar career. And having a tough, caring family was central to her ability to see the humour in the negative.

Not long after her parents, Philip and Valerie, got married, they found themselves sitting on a bus, behind a little girl who was excitedly chattering away non-stop. It was an endearing sight, and one that prompted Philip to say: ‘I want one of those…’

And that’s exactly what they eventually got – a little chatterbox who they named Sarah. The couple already had a small but perfectly formed family when Valerie fell pregnant with their second child. Their eldest, Victoria, was six when baby Sarah was brought back to the Millican family home in South Shields, on the mouth of the River Tyne, east of Newcastle.

It was May 1975, the same year that saw the birth of American comedian Chelsea Handler, comedy actor Zach Braff and presenting duo Declan Donnelly and Ant McPartlin.

It was also the same year that Charlie Chaplin was knighted by the Queen, the same year that the comedy classic Monty Python and the Holy Grail was released, and the first year that unemployment exceeded 1,000,000 in the UK.

Fellow comedians Eric Idle and Steve Furst also hail from the area that Sarah called home – a pretty coastal town that experienced a boom in the 19th century because of its two main industries – shipbuilding and coalmining.

But the last shipbuilder, John Redhead and Sons, closed in 1984, while the last coal pit, Westoe Colliery, stopped mining in 1993 – nearly 10 years after the miners’ strike devastated the north east.

Sarah was a small child during that strike, and was heavily affected by the turbulent times. Her father was an electrical engineer for one of the area’s many pits, and had already seen strike action before Sarah was born.

Philip was a union branch secretary during the 1972 industrial action – a role that taught him a lot about staring down bullies and coming through tough times. And he went on to instil these values in his daughter, Sarah.

The miners’ strike of 1984–85 was an even harsher time in British history – a period that has been immortalised in the film and the theatre hit Billy Elliot, in the BAFTA-nominated film Brassed Off and in countless books. Tens of thousands of miners went on strike to take a stand against poor pay conditions and the threat of numerous pit closures, under Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. A staggering 20,000 jobs were lost as Thatcher took on the unions and it was a period of extreme hardship for the dedicated workers and their families.

Philip was one of those who went out on strike with his fellow miners and it inevitably resulted in tough times for Sarah’s family.

During the year-long strike the family lived on £2 a week, but luckily Philip had talked the local shops into giving the miners bread and other foods past their sell-by date so they could feed their families.

Even then Sarah could see the funny side of the situation. ‘We’d get end-of-day stuff, pies and cream cakes and bashed tins, that sort of thing,’ she has since explained. ‘And then I remember one of the higher-end supermarkets decided they wanted to help out and they gave us 13 trays of avocados, and all of the miners went, “I don’t know what to do with an avocado”. We’d literally never seen one before.’

But even with the handouts their finances were stretched to breaking point, and Sarah’s uncle would spend hours on the beach collecting driftwood for fuel.

Sarah and Victoria had no money for the bus to school and back. Instead they walked everywhere in tight shoes because the family couldn’t afford new ones.

She remembers getting huge blisters on her poor feet, which bled painfully. Sarah suffered in silence, even when her feet were hurting. ‘I didn’t say anything because I knew we hadn’t any money for new ones,’ Sarah told the Sunday Times in an interview. ‘But then Mam went to social services and they said to her: “Hasn’t she got wellies?” So I ended up wearing wellies all summer.’

The strike marked the end of lunchtime trips home, as there simply wasn’t enough food for the family to have three meals a day. Instead the two sisters ate school dinners for the first time.

‘We got free school dinners for a year and the dinner ladies used to give us extra helpings because they knew that was our meal for the day,’ she recalled in an interview with the Observer in 2011. ‘We didn’t really know what was going on except that there wasn’t much money to spare. My sister still can’t look at spaghetti hoops because for ages that was all we had.’

As with all her tales of woe, this recollection is almost Shakespearean in its comedy. Millican’s formidable talent lies in her ability to dig deep into her past for almost tragic events that will make her audience howl with laughter. It’s a coping mechanism that has helped her get through tough times on countless occasions. It gives her very human brand of comedy a universal appeal.

‘I think you have to go through things like that to learn the value of money and to know you can actually survive on very little,’ she says.

Through her comedy, Sarah tries to convey a very profound message: we’ve all been through tough times, but there comes a certain point when we can laugh about the sad things that have happened to us. She takes those times and reminds us of them with style.

Sarah’s mother, Valerie, was disabled and used a wheelchair. She’d had polio as a child, leaving her weak and in pain, but also with a dark sense of humour – something she passed on to both her daughters. In fact, Sarah’s sister Victoria was herself a funny and feisty child, who now says that the only difference between Sarah and the rest of her family is that Sarah gets paid for being funny.

Sarah loved her childhood, and despite it certainly being tough, insists that she never felt it was a tortured existence. Valerie was the perfect stay-at-home mum and Sarah fondly remembers coming home from school every dinnertime to find soup on the stove and her slippers warming on the pipes round the boiler. She was a protective parent, who wouldn’t let her children eat ‘space dust’, or ‘fizz-wizz’, the popping candy that was so popular in the eighties – because she thought it was drugs.

At home, Sarah showed her performance skills from an early age, often tap-dancing and performing poetry for her family, who were unfailingly encouraging. But she was also a shy child and admits she was very introverted. When she performed those poetry recitals they were more often than not from behind the lounge curtains. ‘I guess I wanted to be heard and not seen,’ she has since joked.

Unlike a lot of comedians, it certainly wasn’t in the playground where she first honed her funny skills.

‘I was the timid, mousy one in the corner, who wasn’t popular and was swotty,’ she once explained. ‘But I did appear on stage at primary school.’

Unfortunately her acting debut didn’t go well. ‘I was Mary, but I refused to hug the doll as it was nasty and had pen scribbled on its face. After that my acting career was over, so I was chosen as the narrator because I have a clear speaking voice.’

She was a clever child, who wore glasses from the age of six and never learnt to ride a bike. Instead she had an imaginary library, from which she would lend invisible books and hand out fines for late returns. On Monday mornings at school her classmates would write accounts of their weekends. Sarah’s would mostly say: ‘I played in my bedroom.’

She didn’t mix very much with other children. ‘I was never really part of a clique at school and was very much an outsider,’ she told one Leicester newspaper in 2011. ‘But in some ways I think that helps you become a better comedian.’

She admits she wasn’t a popular child, but is always philosophical about her early years, saying that kids who do their homework well and on time, ‘rarely have many friends’.

Her family wasn’t wealthy, and Sarah didn’t wear trendy clothes or shoes. At the time she wished that things were different, and looked up to the cool kids, but in hindsight is glad that she wasn’t part of their popular crowd. ‘That’s the kind of thing that makes you a comic – that little bit of resistance,’ she says.

Family holidays consisted of long drives through Britain with a campsite at the end. Sarah says that her dad didn’t like stopping the car once he’d started, ‘so he’d try to drive from Newcastle to Cornwall in one go. My mother would make him a pint of coffee before we left, so he’d be forced to stop and go to the loo, which meant we could go too.’

It’s a story that most kids of her generation can identify with, and one that sums up Sarah’s early life quite neatly: her childhood was, in the main, fairly normal. An avid book reader, she was an excellent speller, and was very proud of her intellect. She certainly wasn’t afraid to correct the mistakes of others.

Her father recalls that one time when he was in hospital, Sarah spent her visiting time intently reading his medical chart. Eventually she looked up at the doctor and said: ‘It’s a pity you can’t spell ‘fistula’ correctly.’

Everything that Sarah did as a child, she did to the utmost.

‘If she had rabbits, she’d learn everything there was to know. When she had guinea pigs, it was the same,’ her father told the Sunday Times in a 2011 interview. ‘She took a book to school once to prove that rabbits don’t eat lettuce. To be fair it didn’t make her any friends. She was the class geek.’

It was this strength in character and eye for detail that would push her to excel at being a comedian. At early gigs, she would always record her performances and watch them back to monitor the audience’s response to each of her jokes.

Her talent for making people laugh may appear effortless, but it is the result of a very intelligent and intense approach to her work: when Sarah does something, she does it well. ‘I really believe that hard work pays off and I always try to make sure something’s good,’ she says of her comedy work.

Sarah was a determined child who desperately wanted to succeed and become the best at something. As a youngster, she used to read the local newspaper and see stories of children her age who had won trophies for tap-dancing, or ballet. ‘They had red lipstick and blue eyeshadow on and 14 trophies and I remember saying to my mum, “I’m not good at anything yet!”’ she told the Daily Telegraph in March 2012. ‘I was horrified by the thought that I didn’t have any trophies, and I was, like, seven.’

But her father was the sort of man who refused to accept there were things you ‘couldn’t do’, and didn’t tolerate laziness. ‘He’d say: “The only thing you can’t do is stick your bum out the bedroom window and run downstairs and throw stones at it.”’

The unfailing love and support she had from her parents meant that she had a happy home life. She idolised her father and still looks up to him today. Philip even has a guest spot on her TV show, where he shares his own style of ‘dad advice’ with her millions of viewers.

‘Irritatingly he’s nearly always right,’ Sarah says. ‘My mam used to say: “I knew he was Mr Right, but I didn’t know his first name was ‘Always’.” He’s a good man, my dad. I don’t mean a nice man, that’s not the same. He’s someone you could trust with your life. He’s kind, thoughtful, moral and sort of selfless. He just always does the right thing.’

Sarah was mercilessly bullied at school. Although never physically hurt, she endured a lot of upset at the hands of her classmates. ‘It wasn’t punching or locking me in a cupboard, but it wasn’t any less hurtful,’ Sarah has said. ‘I was a swot. I was good at school and I got on well with the teachers.’

In fact she got on better with her teachers than her fellow classmates, something that her straight-talking mum told her was never going to help her make friends. ‘It did make for rubbish parties,’ she admits.

She remembers vividly the day when someone pointed out a letter in the problem page of teen bible Just Seventeen. The headline was: ‘Am I A Boring Square?’ Sarah was cruelly asked whether she had herself penned the problem page letter.

Her mum Valerie knew from her own experience of classroom bullying how tough it must be for her daughter. Her advice was to simply ignore the taunts.

‘I remember thinking that there must be something more that I can do, a better way to retaliate,’ Sarah recalled in an interview, years later. ‘But my mam said they’ll stop when they’re not getting the reaction they want. She was absolutely right.’

Sarah was again defiant in the face of her tormentors. And to this day she still holds a grudge. Now a household name, she often gets friend requests on social networking site Facebook from the very people who used to make her life a misery.

‘You get a friend request and it’s quite satisfying being able to reject them,’ she told one newspaper recently. ‘I didn’t like you at school, I’m not going to like you now. I hold massive grudges. I’m really good at grudges.’

At the time, her father was her inspiration for coping with the bullies. Sarah acknowledges that she gets a lot of her positivity and drive from the former engineer, who would tackle the bullies who followed his daughter home and constantly encouraged her to work hard, despite the teasing that her tenacious attitude to schoolwork brought her.

Sarah – a chatty and pleasant child at home, so different to her quiet nature at school – tried to hide the bullying from her parents.

One of only two children in her year who wore glasses, she got called names every day, particularly ‘Norma No Mates’ and ‘Speccy Four Eyes’. The name-calling hurts to this day. When one interviewer for the Guardian joked last year that he preferred Norma No Mates, because Speccy Four Eyes ‘wasn’t that personal’, Sarah got very defensive.

‘Don’t tell me what’s hurtful when I’m seven. How do you know what’s hurtful for me?’

The interviewer tried to diffuse the situation by saying that he’d meant it as a joke, but Sarah didn’t take it that way. It’s clear that being bullied at school is not something she will ever forget. But it has become a part of what defines her. Sarah is a strong and capable woman, who turns negative experiences into good ones by seeing the funny side of them.

Hers is a very personal kind of comedy, which is why so many of us identify with her stories and jokes. But we all know, deep down, that they are real. And for her to really share these experiences she has to feel them all over again – which must still hurt to some degree.

As a child Sarah quietly ignored the bullies, until her sister couldn’t stand to see it any more. Her father recalls: ‘It was her sister, Victoria, who told us. There was a girl who’d grab her arm and scrape a playing card down it, till the skin flayed off. What hurt most was that she’s the sort of bairn who’d do anything for anyone. But some mistake kindness for softness, and she’s not soft. I went through everything that she went through and eventually you learn to stand up for yourself.’

When Philip learned what was happening to his youngest, he took matters into his own hands. At the time Sarah wrote in her diary that her dad had ‘put the fear of God’ into one particular girl. She was a few years older than Sarah and used to follow her home from school regularly, muttering nasty things under her breath. For the young Sarah it was traumatic and finally she pointed the girl out to her dad. ‘He told her it was harassment and that he would ring the police. It worked,’ she says.

Philip’s actions inspired her to go one step further and stick up for others like herself. He remembers Sarah coming home one day grinning from ear to ear. ‘I remember her telling me that the teacher had asked her to pick the netball team, and she picked everyone who’d never been picked before – the fat ones, skinny ones, short-sighted ones… She said: “Dad, we got hammered 26 nil, but it was the best day of our lives.”’

When she grew up Sarah wanted to be either a pixie or a stripper – because she thought they’d both be glamorous dancing roles. But her first real ambition was to be a vet, because of her love for animals. As a child she nicknamed herself ‘The Hamster Squeezer’, because she had a tendency to hug her pets that little bit too hard.

In her teens she went for work experience at a veterinary hospital, where she genuinely thought she would spend her time handing out medicine to sick pets. ‘It was horrific,’ she has since said. ‘I thought you just stroked rabbits, you know, gave them tablets. Then they said, “Do you want to sit in on some operations?”’

Watching someone’s treasured pet go under the surgeon’s knife put paid to Sarah’s veterinary ambitions, as the reality of a vet’s job was revealed in all its gory glory.

Sarah was – in her own words – a late developer, and boys weren’t a big part of her teenage years. ‘I liked boys,’ she told the Scotland Herald in 2010. ‘But they didn’t really like me. And the boys who did like me, I didn’t like. One boy bit off his wart and showed me it. Somebody leaned over and said: “He loves you”. That’s apparently why he did it. It had an impact. I’m not sure it was the impact he was looking for.’

And Sarah did her best to throw off any advances that did come her way. ‘I’d get asked out for drinks but I thought if a boy buys you a drink you had to have sex with him and I wasn’t going to do that, so I made bloody sure I had a drink of my own,’ she explains. ‘I had a slightly ice maiden quality, which I liked, because I don’t think you ever meet anybody you’re truly meant to be with in a lairy nightclub when everyone’s hammered, you can’t hear what anybody’s saying and the only thing you’ve got in common is you’re both in the same location.’

It was a wise observation for one so young, but it did mean that her experience of dating was limited – a fact that would bring her heartache in the years to come.

She recalls one disastrous occasion when she brought a boyfriend home to meet the family. The story she tells about that time is teeming with exactly the kind of black comedy that Sarah insists comes from her parents.

‘My mam has a picture of Marilyn Monroe dated 1953, and – as if it’s the most normal thing to say in this situation – she turns to him and says, “That’s the year I got polio.”’

The family actually celebrated that anniversary in 2003, with a cake with ‘50’ piped on it. Confused diners at the restaurant they were in thought it was her mum’s 50th birthday. As Millican herself says: ‘And she wonders where I get my dark humour from…’

In an attempt to bring her shy daughter out of her shell, Sarah’s mother got her a Saturday job at the local WH Smith, where she carried out her duties as diligently as her schoolwork. Blossoming into a creative and intelligent woman, Sarah wanted to go to university, but knew that her family’s finances wouldn’t stretch to such a big expense.

When the strikes were over, Philip had gone back to work at the mines, but the family had continued to struggle financially. Millican didn’t complain. ‘I knew that the only way they could afford for me to go was if I stayed at home, and I knew part of university was to make beans on toast in a bedsit and have parties. My dad was working seven days a week and I didn’t want to put any more pressure on him.’

Sarah saw her family as a close-knit team, and as part of this special group there was no room for selfishness. If something that she wanted would make life difficult for the rest of her family, then she would simply stop wanting it.

From the tender age of 15 Sarah knew that she wanted to work in the media in some way. When someone unhelpfully pointed out that she needed a degree for that kind of career, she just ignored them. So after her A levels, Sarah did a course in film and television production as a way of keeping up her creative interests – but with no thought of putting herself in front of the camera. She tried to get into television production in nearby Newcastle, but there were few jobs, so she was unsuccessful. Then followed a stream of unfulfilling roles in jobs that couldn’t even begin to challenge the clever comic-to-be.

She worked in a call centre, and then as a producer for audio books. She is still amused by the title of one Mills and Boon book she recorded in the course of her work: Once Upon A Mattress.

‘It seemed to happen that we always read sex scenes on a Sunday morning,’ she has explained. ‘Which seemed so wrong in so many ways.’

When she turned 18, Sarah found work in a local cinema, with people she had never met before. It was a fresh start for the once shy girl, who suddenly found herself popular. She was astonished by how many people liked her and is remembered by her former colleagues as a feisty and funny character.

She continued to fill her spare time with creative projects, taking several night classes each week in subjects like creative writing and film editing. She regularly wrote a film column for her local paper, and made numerous short films with her new friends.

Her subject matter always had a funny angle to it, because that was what she enjoyed. It was obvious that Sarah was bursting with creativity and needed an outlet…