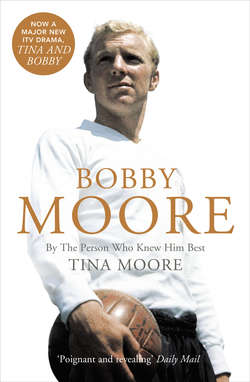

Читать книгу Bobby Moore: By the Person Who Knew Him Best - Tina Moore, Tina Moore - Страница 6

CHAPTER ONE Hero

ОглавлениеHere’s my Bobby now. Head up, sunlight on blond curls. He’s been out there for nearly two hours but he looks so elegant and calm he might just have stepped onto the pitch.

He’s chesting the ball down. A short pass to Bailie, who passes it back, socks down around his ankles. Bobby looks up. Where to now?

I can feel Judith Hurst’s fingers tighten on my arm. Out of the corner of my eye I catch sight of Geoff, exhausted but still instinctively heading for the German goal.

Oh Bobby, don’t risk it. Big Jack Charlton’s screaming at you. No one can hear what he’s saying, all we can see is his Adam’s apple wobbling, but it’s what we’re all thinking. We’re 3-2 up! We’re in the final minute! Kick the % *#$ thing into the stands!

Judith and I are clinging to each other, the way we’ve done for most of the game. Every conceivable emotion has been wrung out of us - pride, rapture, excitement, despair, euphoria, disbelief, hope, agony, exhilaration. We clenched our fists in anticipation when Martin Peters scored with twelve minutes to go. We plunged our heads in our hands when the Germans equalized with just moments of normal time remaining.

We watched the shot from Geoff bounce in off the crossbar in extra time. Or did it hit the underside and bounce out again? Wasn’t it a goal after all? Judith was shouting, ‘It’s in, it’s in!’ and I was backing her up with, ‘Oh yes, it’s in!’ The German supporters behind us were shouting back, ‘No it isn’t!’ We must have sounded like the audience at a panto. But it was all right. Goal given. 3-2.

The World Cup is nearly ours.

Now the German supporters have fallen silent. A few seconds of tension seem like an eternity. Bobby finds Geoff, running way upfield, with the perfect ball. People start running onto the pitch. In living rooms all over the land Kenneth Wolstenholme is telling the nation, ‘They think it’s all over . . .’

Geoff’s puffing out his cheeks, the way he always does when he shoots. The ball lands in the net. And to continue with those words of Kenneth Wolstenholme, which I think everyone in England must know by heart,’. . . It is now.’

There’s too much noise to hear the final whistle, but around me is an explosion of delirious joy. I just sit in silence for a few seconds. I’m drained, physically and emotionally. The roller coaster of the last eighteen months that Bobby and I have lived through, the public adulation and success, the private terror and uncertainty, have suddenly got to me. I can’t take this in.

I don’t stay still for long, though. Judith and I are out of our seats, hugging each other. I think of Doss, Bobby’s mother, who’s spent every game of the tournament pottering around the garden because she can’t bear the suspense of watching Bobby. Now she’ll be so proud and overjoyed.

Bobby climbs the steps. He glances at the Queen’s lilywhite gloves and carefully wipes his sweaty, muddy palms on his shorts then dries them on the velvet balustrade before receiving the trophy. I can’t help smiling. It’s such an elaborately thoughtful gesture, so typical of Bobby. Mr Perfect.

And when he holds up the cup, I cry. Not out of happiness because England have won but because of what he’s been through to be standing here today with the Jules Rimet Trophy in his hands. Watching him being carried round on his team-mates’ shoulders, I just think how magnificent he is. Here’s someone who, only a year and a half before, unknown to all but half a dozen people, has undergone a terrible ordeal with cancer and overcome it. Now he’s every schoolboy’s hero, holding up the World Cup. To me, that’s the real magic of the day. What a man.

The thirtieth of July 1966 must be a date branded on every English person’s memory for all time. Even people who weren’t born then know about the day we won the World Cup. It’s part of British history. It was a unique occasion. Even if we won it again (wouldn’t it be great?), the boys of summer 1966 will always have a special place in everyone’s hearts. They were the first.

When I think back on that time, the sun always seems to be shining in my mind’s eye, although in fact it rained on the afternoon of the Final. It must be something to do with the era in which it took place. The Boys of ‘66 were part of the fabric of the Sixties: Swinging London, the Harold Wilson government, student protests, flower power, the Beatles and the Stones, white boots and mini-skirts, Biba and Mary Quant. It was a gorgeous, glorious time when the whole of Britain seemed youthful, successful and optimistic.

As Judith Hurst and I were driven in an England bus with the rest of the wives past the throngs of people in Wembley Way that day, we felt so proud and full of expectation. And the first people we saw when we took our seats were Terence Stamp and Jean Shrimpton, who was probably the face of the Sixties. She looked so glamorous, absolutely stunning. I had done a little modelling for a couple of catalogues but I just wasn’t in her orbit. She was the real thing. I couldn’t take my eyes off her. She just stood out.

The build-up to the Final had been overwhelming. Wherever you went, it was all anyone talked about, but I could still hardly believe what was happening to us. Yes, it was a time when the class system was breaking down and people from ordinary backgrounds like us were beginning to become cultural icons. And yes, Bobby had already become football’s first pin-up - Terry O’Neill’s photo of him, surrounded by models, had appeared in an edition of Vogue in 1962. Not only that - he had just graced the fashion pages of the Daily Express, kicking a ball in a Hardy Amies suit. But this was something else again. Before the World Cup, I’d been able for the most part to go about with my family in anonymity. But in those weeks leading up to the Final I had my first taste of what it meant to be a celebrity, just for being married to a footballer.

I was being recognized in Bond Street. Shops would loan me designer clothes. Alfie Isaacs, a huge West Ham fan who owned an upmarket dress shop, gave me the outfit I wore on Final night - yellow silk chiffon with a flared skirt and a beaded top that I teamed with a tourmaline mink stole. Alfie had arranged for the photographers to be there when I tried it on and they followed me as I skipped up the road on a shopping spree. I caught sight of Alfie peering anxiously at me from round the corner, worrying that his ensemble was going to be upstaged.

Taxi drivers wouldn’t charge fares. I discovered I could ring up a restaurant and say, ‘Tina Moore here, can I have a table?’ and the answer was never ‘No’. Ford gave us a white Escort, although as it had World Cup Willie, a cartoon character, on the side, it wasn’t the kind of vehicle you went anywhere in if you were trying to cultivate an impression of dignity. But let’s be honest, we were having the time of our lives. Loads of doors opened for us because of Bobby’s fame. I realized we were of value. A lot of it was hype and nonsense and I hadn’t expected it, but it was great.

The point I’m making is that suddenly, for the first time ever, the game wasn’t just something stuck at the back of the newspapers. Football had married fashion and now it was feature page material as well. In March that year, Terry O’Neill had taken some fabulous shots of Bobby and me, including one of me leaning against a tree in Epping Forest, wearing thigh-high boots and an England shirt as a mini-dress, while Bobby knelt at my feet wearing drainpipes and a black polo-neck. If we hadn’t known it before, we knew it then - we were Bobby and Tina, the First Couple of football.

My picture also found its way into the Sun, where it formed part of a collection called ‘Ten of the Best-Looking Women in England’, probably because someone thought I looked a bit like Joyce Hopkirk; we both had long, blonde hair. There the similarity ended: she was the editor of Cosmo magazine and one of the most powerful, glamorous women in Fleet Street, while I was a Gants Hill housewife. And I hasten to say that it was a terrifically flattering photo of me - when I first saw it, I thought, ‘Oh, she looks good’ and carried on turning the pages. I hadn’t recognized myself.

Don’t get me wrong. I wasn’t some new, unique star in the firmament - Tina Moore, footballer’s wife extraordinaire. It wasn’t just me on whom the press were focussing. All the players’ families found themselves to be of intense media interest. Martin Peters, Geoff Hurst and Bobby, the three West Ham players in the England side, all lived close by each other in suburban Essex and there were photoshoots in our back gardens, with toddlers crawling around our feet. Pictures of the girls of 1966 appeared in The Sunday Times - elegant Norma Charlton, pretty, coltish Lesley Ball, the lovely, warm Judith Hurst and tall, dark-haired Kathy Peters, looking haughty and Vogue-ish in her miniskirt. In actual fact, the real-life Kathy was one of the least haughty people you could ever meet. She had the most tremendous sense of fun. That girl was a real laugh.

I suppose, in a way, we were the prototype Footballers’ Wives, but rather than being singers and models and celebrities in our own right, we were ordinary girls from ordinary backgrounds who only surfaced in the glare of publicity because we were married to the players. There was no pretentiousness or ostentation. Nobody was trying to cut anyone else out. There wasn’t a big hairdo amongst us and we would have died rather than do anything that led to accusations of being flighty.

Really, we were girls of our time. We’d been brought up to respect our elders and betters and we certainly weren’t swept away by our own importance. Set foot on the pitch or in the boardroom? We’d never have dared. At matches, the wives and girlfriends were always contained in a separate tea room, so if any of us harboured delusions of grandeur we soon got the message - we were of no consequence whatsoever!

For instance, on the evening of the World Cup Final there was a celebration dinner at the Royal Garden Hotel in Kensington High Street. Everyone was there: players and officials of the four semi-finalists, the World Cup organizing committee, the upper ranks of the Football Association. Everyone but the wives. The banquet was stag. In that era, not one of us found that at all remarkable and if Alf Ramsey said, ‘No wives’, then that was how it had to be. There was a wide gulf between managers and players in those days and not one of them would have questioned his decision. In our day we always did what we were told to do.

So we wives were herded into the Bulldog Chophouse in another part of the hotel. The only women allowed into the banquet were the official photographer, Sally Lombard, and her two assistants. One was Estelle Lombard, Sally’s niece. The other was Betty Wilde - who just happened to be my mother.

The explanation? Sally Lombard’s company, Jalmar, held the photographic concession at all the top London hotels. My mother was no photographer, but she and Sally were great, great friends. They went way back. As soon as it looked as if England would make the Final, the two of them hatched the idea between them. My mother kept it a tightly-guarded secret and Bobby and I were both astonished when she told us. What a coup! I wasn’t jealous - far from it. I thought my mother was brilliant to have got herself in.

I didn’t manage to set eyes on Bobby until around midnight, when photographers got us together for a picture on the roof terrace. Normally about as hot-headed as a snowman, that night he was a different man, wild with happiness and excitement, just radiating joy. The trophy was in his hands and I’m not sure who got kissed the more passionately, me or Jules Rimet.

As we left the hotel, I gasped - thousands of people were waiting outside just to get a glimpse of him. Bobby was so moved that he actually couldn’t speak. As for me, that was the moment when it really sank in how much he meant to the fans. Forget the Prime Minister and Prince Charles, forget John Lennon, Paul McCartney and Mick Jagger. That night, Bobby was the most famous man in England.

It was a real shame that there wasn’t a party laid on for the lads and the wives and girlfriends. It would have been lovely to celebrate together. Instead we all split up, with Bobby and I and a couple of the others heading for the Playboy Club. When we arrived everybody stood up and applauded. The atmosphere was just fizzing with electricity. Burt Bacharach was there with Victor Lownes, who ran the club and was Hugh Hefner’s business partner, and he asked Victor to introduce him to Bobby. All the bunny girls were crowding round taking pictures. It ended up with Bobby on stage singing Stevie Wonder’s ‘One, two, three’ -with hindsight, perhaps Geoff Hurst, the hat-trick hero, should have been up there singing that. And I had a song dedicated to me as well - ‘My Cherie Amour’. What a fantastic night.

We got back to the hotel at around 3 am and tumbled into bed, dazed with happiness and triumph. The next day everyone went to the ATV studios, where the team appeared on a show hosted by Eamonn Andrews, and after that we went back to our house in Gants Hill on the eastern outskirts of London. It was our first marital home and cost £3,850. We’d started saving up for it the minute we got engaged at Christmas 1960.

Everyone came to terms with the events of the weekend in their different ways. Geoff Hurst mowed the lawn, then washed his car, the same as he did every Sunday afternoon. Martin and Kathy Peters had gone home early after the banquet because they had just bought a new house and Kathy had dealt with the move on her own while Martin was away with the England squad preparing for the World Cup.

Jack Charlton, several sheets to the wind, famously woke up in a sitting room in Leytonstone, having spent the night on the sofa of a complete stranger. When he tottered outside the next morning, a Geordie voice said, ‘Hello, Jack!’ from over the garden fence. It was a lady from his home town of Ashington, down in London for the weekend to visit relatives.

And the most celebrated man in England and his wife? With our heads still in the clouds, we held a party for our friends and re-lived the day. But after the guests had gone, everything just felt a bit flat, to be honest. Bobby poured himself a lager and tried to settle down to watch television, while I cleared up the glasses and looked back on the last eight weeks.

I’d loved every minute of it, of course I had. It had been heady and exhilarating, but a bit crazy, too. And with Bobby away with the team most of the time, I hadn’t been able to share the fun with him. Now we were back to normality. It was time to come down off the clouds, I thought. I didn’t know whether I felt relieved or bereft. Both, perhaps.

Whatever I thought normality was, we weren’t back to it for long. I realized that when the telegram dropped onto the doormat a few days after the Final. It gave a date, followed by the message: PARTY STOP WOULD LOVE TO SEE YOU STOP LIONEL BART.

We were really excited and nervous. When we asked around, we found it was going to be a real showbiz party, so I went out to buy a new dress. It was green lace and knee-length. On the day I had my hair done specially, with a hairpiece that fixed on with an Alice band. Confident that I truly looked the part, I set off with Bobby to Lionel Bart’s house.

It was wonderful. I’d never been inside anything like it. The walls and ceiling of the guests’ cloakroom were all mirrored and the loo itself was set in a huge golden chair. You really could claim to be ‘on the throne’! Bobby and I were shown into a room full of guests. It was like walking into a photograph of a cross-section of Sixties glitterati.

Bobby and I weren’t complete hicks. We were living in an age when working-class people were starting to make a lot of money in fashion and showbiz. Football was part of their roots, so naturally he was one of their heroes. We’d already started to rub shoulders with some of his up-and-coming East London contemporaries - Terence Stamp, who came from Plaistow, the same stamping ground as Martin Peters, was one of his drinking buddies, and Kenny Lynch, the entertainer, had been a mate ever since they’d met at the Ilford Palais, in the days when Bobby was captain of England Schoolboys.

Then there was Dougie Hayward, the so-called ‘celebrity tailor’ in Mount Street, Mayfair. Dougie, who made suits for Michael Caine, Tony Curtis, Peter Sellers, Kirk Douglas and the racing driver Jackie Stewart among others, was another East End boy who was mad about football. I bought Bobby one of his bespoke green velvet smoking jackets.

Johnny Haynes, the last England captain but one before Bobby, had introduced us to the White Elephant, a private dining club in Curzon Street; it had been a favourite haunt of ours for a long time because Bobby was never interrupted by autograph-hunters there and we could enjoy a night out undisturbed. Because it attracted all the main stars of the time, we’d met Robert Mitchum, Sonny and Cher, and Sammy Davis Junior.

But this wasn’t an exclusive club we were in; it was a celebrity’s home. I quickly took in the presence of Tom Jones, Joan Collins, Anthony Newley, Alma Cogan, some of The Who, one of the Stones. The odd thing was that they were all sitting on the floor, though after a while I spotted an empty chair. By then, Bobby and I had had a couple of glasses of champagne for Dutch courage, so I clambered across all these famous people and sat down in it.

I had Joan Collins sitting on the floor on one side of me and Anthony Newley, her then husband, on the other.

‘Who is she?’ Joan Collins whispered to Anthony Newley as she looked up at me.

‘I don’t know,’ said Anthony Newley, ‘but I think she’s sweet.’

The penny dropped. ‘I’m not meant to be here,’ I thought, and tripped back to where I’d come from. I had suddenly realized that the throne might have been in the loo but the chair was the next best thing, and the king who was meant to sit on it was Bobby.

Bobby was the son of a gas-fitter and I’d been a junior secretary at Prudential Assurance. We’d always been in awe of these celebrities, but as far as they were concerned it was Bobby who was the star. As I looked around, watching them all queuing up to shake his hand, I studied what Joan Collins was wearing - a crocheted mini-dress and Courrèges boots, under one of those angled Mary Quant bobs.

‘That’s the last time anyone ever catches me in a knee-length dress and false hairpiece,’ I thought. ‘This is it. The big time. From now on, it’s sink or swim.’

A few weeks later, I was faced with the choice of sinking or swimming again but this time literally. The government of Malta had invited Bobby and me to visit the island as representatives of the World Cup winning squad and we set off in great spirits, excited about seeing Malta and the neighbouring island of Gozo. Met by a tumultuous welcome, we felt close to achieving Royal status as we were taken on an open-topped motorcade tour of the local stadium.

That was where the problems started. Before the trip, inspired no doubt by my close proximity to Joan Collins, I’d had my blonde locks cut short at Vidal Sassoon. It was a disaster! I hated my new geometric hairstyle so much that I invested in a long blonde wig. It made me feel more like myself, but by the time we were roaring around Malta in the motorcade, it was shifting in the breeze and I wasn’t feeling very optimistic about its future prospects.

The wandering wig set the tone of a trip that had us alternating between shuffling exhaustion and convulsions of laughter. We had a very tight schedule and although the Maltese people were fantastically warm and hospitable, we were finding things very draining. Bobby only had to appear at the window of our hotel room in the mornings to be greeted with cheers and applause for, as he put it, ‘the great feat of opening the curtains’.

So we were very grateful when they gave us one afternoon’s rest, which allowed us to spend some time on a local businessman’s yacht. The weather was gorgeous and we were offered the chance to water-ski. I had to refuse the invitation in case the blonde wig went walkabout, which was quite galling, although we did get to go on a speedboat and with the help of a red scarf I managed to keep my hair on. At the end of a fabulous afternoon, the speedboat bore us back to port where we were due to meet a prominent Maltese monsignor and a couple of government ministers.

It so happened that the day before our yacht visit, Bobby and I had run into Mike Winters, one half of the Mike and Bernie Winters comedy duo, and his wife, Cassie. They were holidaying out there. Cassie, who was heavily pregnant, turned out to be not just a lovely person but a real character. Not only that, but she must have been psychic as well. Her parting shot to me was, ‘I’ve got a feeling about you. You’re going to be front page news one day.’

In fact, her prophecy was proved right a little bit quicker than that. Within forty-eight hours the front page of The Maltese Times was carrying huge banner headlines saying: MONSIGNOR AND MRS BOBBY MOORE IN SEA DRAMA.

What happened was this. As our speedboat reached the shore, a gangplank was extended for us to climb off. Very gingerly I stepped onto it. At that moment there was a slight swell and I grabbed at the bishop’s extended hand. It caught him off guard. Over my shoulder went one priest. As he went flying towards the water, the Minister of Sport tried to catch hold of him and fell in with him. With me already on the gangplank and Bobby about to step onto it, the boat rocked, the gangplank gave way and we went into the briny too.

It gets worse. The wig which I’d so carefully guarded all day was soaked and dyed red from the scarf. I must have looked like a victim of a shark attack, especially as my knees and shins were grazed and bleeding. I was wearing a navy crepe mini-dress and that was up to a daring new high, so it was just as well the monsignor’s glasses had fallen off and sunk to the bottom.

BOBBY MOORE IN HEROIC SEA RESCUE ATTEMPT? No way. He was far too busy desperately trying not to crack up with laughter, in case he hurt anyone’s feelings. But the funniest thing was what my mother -ever my publicist - said when a reporter rang up for her reaction: ‘Oh, I’m sure Tina’s all right. She’s a very strong swimmer.’

I was in the Cipriani restaurant recently, chatting with my friend Marilyn Cole, the British Playboy bunny who became Playmate of the Year, and we were talking about England’s 2004 European Championship defeat by Portugal. I can’t imagine that forty years ago a glamorous woman like Marilyn Cole would have been discussing whether a divot had caused David Beckham to miss a penalty.

It’s different now. Can you imagine the World Cup winning captain of England going back to his Essex semi to sip lager and watch TV? Can you imagine the hat-trick hero being able to wash the car outside his house the next day without being mobbed?

There’s no way today’s up-and-coming football apprentice would have to bump up his pay by working as a labourer. Bobby did. In his teens he had a summer job at William Warnes, the factory where his mother worked. As it happens, that job and the chores he had to perform as a colt for West Ham - sweeping the stands and rolling the grass - were things he liked doing because they built him up; although he had strong thighs like tree trunks, his arms were like twigs. I think he knew he had the makings of an Adonis!

That Saturday in July 1966 changed everything. The minute Bobby held up that trophy at Wembley, football was never going to be just a sport any more. It wasn’t only the fact that England won, either. There was something about Bobby himself, his blond good looks, his style, the way he carried himself. You don’t often hear a man described as beautiful, but that’s what Bobby was. He looked like a young god - one who happened to play football.

He was a complicated young god. As a husband and father he was warm and loving. As a player he was cool and undemonstrative. His temper was so controlled and his tackling so accurate that he was almost never booked. He had a ruthless, calculating streak - if someone hurt him in a tackle, he would never react in the heat of the moment, but store it up for later and make his point when the time was right. To have that icy self-control turned against you was devastating, as one day I would discover. But those qualities were part of what made him the great England captain we all so admired.

Bobby and I were the first to experience the good and the bad of post-1966 football. We bought the dream house and lived the fabulous lifestyle. We were courted by Prime Ministers and befriended by celebrities. We had to cope with the glare of the media and the tensions which that caused in our marriage. We had kidnap threats to our children. All firsts.

Bobby’s bonus for being part of the World Cup winning side was £1,000. Now that seems like a pittance, but in any case to him that wasn’t what it was about. It was about putting on that shirt with the three lions on the chest and hearing the roar of expectancy when he led the team out of the tunnel. Some kind of charge went through him the moment he put on that shirt. He seemed to turn into a lion himself.

I can see him now, the ball resting on his hip. Then he’d knock it into the air with the back of his hand before breaking into a jog, running with those little short steps and holding down the cuffs of his long-sleeved shirt with his fingers.

He was so proud of being an England player. He liked the fame, he loved the big crowd and above all he believed in his country. He showed it by the way he played. I think that’s why he’s remembered with such love and why so many people continue to look on him as the greatest English footballer there has ever been.