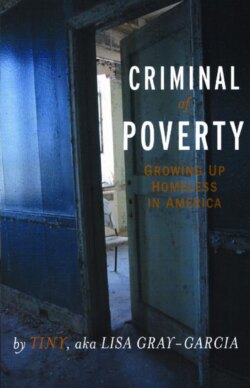

Читать книгу Criminal of Poverty - Tiny aka Lisa Gray-Garcia - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

preface

ОглавлениеCamping citations up by 255% in San Francisco … One out of every seven families are at-risk of homelessness in the U.S. … In 2003, the number of Americans living in poverty rose by 1.3 million …

It’s illegal is to be homeless in America. Poverty is a violent crime. Like thousands of unheard, unseen, very low and no-income children, families and individuals living in poverty in America, I have been incarcerated for those crimes. I am a criminal of poverty.

This is my story, my mother’s story and my grandmother’s story—three generations of poor women in America. It focuses on the criminalization of poor families, poor women, mothers and children, through the telling of one family’s struggle with poverty and homelessness.

My story also illuminates the root causes of poverty through the story of three generations: my grandmother, an Irish immigrant, teenage mother and battered woman in pre-New Deal patriarchal America; my mother, a mixed-race child surrendered to foster care, a survivor of abuse who tried for many years to escape her childhood torture until one day the struggle became too great; and finally me, a daughter raised by a poor single mother who lived “one paycheck away from homelessness” until finally there was no longer a paycheck to keep us housed, a daughter whose duty it was to keep my family alive by any means necessary, a daughter who was home-schooled in the school of hard knocks.

But this is not a rant about what I didn’t have (typical school-system education, traditional family structure, material wealth)—I will forever be grateful to my mother for giving me the best life she could, for giving me strength, intuition, art, her trust and, above all, the intellectual means to understand my situation and develop a pedagogy of poverty.

Rather, this is a condemnation of a system that values independence and separation—children from elders, mothers from children, parents from school systems—rather than interdependence, community, support and care giving. This is a condemnation of a system that makes it hard for all parents to thrive, for poor parents to simply survive, for poor women to raise and care for their children, and for children to help their parents. A system that doesn’t support people who need help, whoever they might be, and instead sets up a pecking order of the deserving and undeserving poor. A system that pits the poor against the poorer.

We poor folks have bought into that same belief system; we rarely recognize the root conditions of systematic oppression that have brought us to where we are. We are ashamed of our “mistakes,” we are ashamed of our poverty and too often we are ashamed to ask for help. So, after we have finally lost all hope, tortured by our internalized shame and our psychiatric diagnoses, floundering in shelters, SRO hotels, in our cars or on the street, then we arrive at the point where someone else is deemed better qualified to make “our decisions” for us: “They’re too sick to be on the street”; “That child should be in foster care”; and on it goes.

“We need to clean up this neighborhood.” When we hear those hygiene metaphors we need to be conscious that the human beings who are being “cleaned up” and “cleaned out” are people of color, poor, homeless, youth, elders, someone functioning with a substance abuse problem, living with a mental illness or other disability, living in a car, migrant day laborers, etc. Or they could be people whose work is not recognized as work, such as panhandlers, street newspaper vendors, recyclers, and/or workfare workers. These people, if they happen to be dwelling, sitting, sleeping, and/or working in a neighborhood that’s undergoing gentrification/redevelopment, will be targeted by the police for harassment, abuse, arrest, and eventually incarceration.

The clearest example of this process was the “clean-up” of New York’s Times Square under the mayoral administration of Rudolph Giuliani. In the 1990s, while HUD was reducing its overall budget by 90%, and simultaneously demolishing housing projects and exchanging housing for mostly useless and unredeemable Section 8 vouchers, Mayor Giuliani launched his Clean-Up New York campaign. He began with a proclamation, “Panhandlers, peddlers and prostitutes must be cleaned out,” making a public link between sex-workers, unlicensed vendors, street artists and panhandlers. He presided over a racist, classist effort to purge the city of any visible trace of its vast number of poor and low-income inhabitants in a push to create a Disneyfied, tourist-friendly city. Giuliani’s “clean-up campaign” was so successful in achieving that goal that it became the model for cities across America as they strove for more tourist dollars, redevelopment money and real estate increases.

Cities like San Francisco, Atlanta and Sarasota have followed suit. Homeless people, poor intergenerational families, youth of color, migrant workers, these are always the first to be “cleaned out.” The shelter systems to which they are remanded are usually run by large corporate developers who get million-dollar contracts to provide beds and some kind of integrated case management services. The whole system then operates like a pseudo-jail, with nightly piss-tests, integrated welfare/workfare at slave wages, most of which must then be used to pay for the homeless person’s bed, and a tiny cash grant which barely covers luxuries like aspirin or toothpaste.

Shelters, however, are still not truly incarceration. Poor folks actually get jailed for many reasons, most of which have to do with simply being poor. Crimes of poverty can include violations for the act of being homeless and/or very low-income in America, such as camping on public property, blocking the sidewalk, recycling, loitering (which can include sitting while homeless), and in my family’s case, sleeping in a vehicle or driving with expired plates (Driving While Poor). Other crimes of poverty might fall into the category of the “undeserving poor,” for example, a family barely subsisting on welfare is convicted of welfare fraud for lying on a form to receive medical care or extra food stamps, “crimes” that many poor parents get accused of. These and other crimes of poverty and homelessness are increasingly common all over the United States, especially in cities like San Francisco with its scarcity of affordable housing and high-speed gentrification, redevelopment and subsequent destruction of low-income communities. The experience of being put in jail for crimes of poverty can destroy a person’s mental and physical state so entirely that one can lose the strength to go on about the business of survival as a poor person or, even worse, a poor parent.

Mine is a story of survival, common to many families subsisting in poverty in the United States. Like many of my sisters and brothers in the third world, it was necessary that I work to support my family, rather than take part in a formal education that makes no allowances for the erratic schedule of a working/houseless child. Contrary to Western capitalist standards where healthy families are made up of individuals whose personal advancement and fulfillment are considered paramount, I am honored that I could help my family, that I could help my mother, and like poor children all over the world, I am aware that without my help, she would not have made it. In our pathologically self-centered modern society, where we are all expected to survive and prosper in a cut-throat economic system that does not provide child care, housing, healthcare or a good public education, mine is not only a story of survival but of triumph. And above all it is a call for vision and clarity: the denunciation of the oppressive system that drives people into poverty and keeps them there, and the recognition that first and foremost all people deserve whatever help they need.