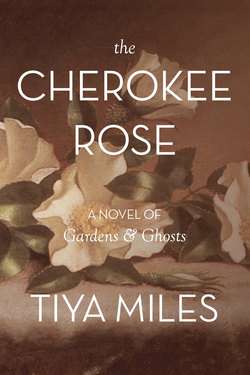

Читать книгу The Cherokee Rose - Tiya Miles - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPrologue

Dust to Dust

She failed to heed the warning when the men began to dig in the Strangers’ Graveyard on the outskirts of town. Negroes were buried there, and Indians, too, and Indians who were mistaken for Negroes. The man with hard, iron eyes and hair the color of river sand was the first to break ground. Wielding his blunt-edged shovel like a knife, he tore into the tender earth, displacing soil and sediment heap by heap. He was the leader, the master, the maker. The others simply followed, plunging into the people’s bones with lock-jawed excavation machines.

The Strangers’ Graveyard had rested in peace for more than a century, floating out of place and time. It had been forgotten, an island of brambles and spindly trees, except by those who cared for it and those who cared nothing for it. Once, many years ago, the graveyard trees were sentries with bottles of colorful spun glass suspended from their branches. But now their powers of protection were lost, and the burial ground lay naked. It was open land, good land, valuable land in the sand man’s eyes.

Trucks dumped mounds of dirt into adjacent refuse piles, the faded bones of human remains churning beneath the wheels. A collarbone, bleached and brittle. A skull with sunken sockets for eyes. The far-flung skeleton of a small slave child. The sand man, unperturbed, instructed his crew to lay a foundation. While workmen mixed thick cement and cut the flesh of trees to size, the man began to prowl and prod the vast perimeter of his property. His daily walks spread farther and wider until he reached the line. He eyed the river and the cane beyond his acreage, the hill and sun-kissed fields. On the day his crewmen poured cement on the site of the gutted burial ground, the sand man crossed the border and entered the dwelling place. He strode the Cherokee Rose Plantation, land not his own, grasping a shovel and brittle map, stomping white roses to force a pathway.

She had crossed a border, too. She had crossed the bridge. Watching him closely from beside the attic dormer, she peered down the slope of the overgrown hillside. Beyond the graceful brick façade and covered rear veranda, beyond the yard where slaves had toiled and medicinal plants had grown, lay buried the dreams of her foremothers. The sand man consulted his map, shifted his shovel, and plunged it into the ground. She feared the worst. Matricide. A way must be found to gather descendants—bone of her mothers’ bone, flesh of her mothers’ spirit. To call upon them—the ones who came later and had no memory—to know and protect the past.

Dust motes floated like cottonwood spores in the dappled sunlight around her. She breathed softly against the house and felt the attic walls expand. Reaching for the brass latch that sealed the half-moon window shut, she turned its rigid thumb and pushed. Warm, sky-born air sprang into the garret. The dust of two hundred years flew into a shifting wind.