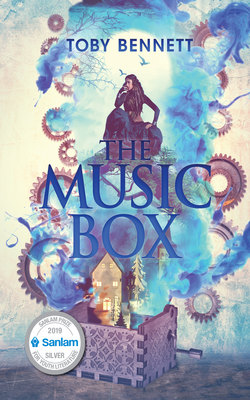

Читать книгу The Music Box - Toby Bennett - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 2

ОглавлениеAn Unwelcome Visitor

John woke early to the hammering of his alarm. He shivered as he dressed; the weather was much chillier than he’d anticipated. He had to stop his teeth from chattering as he put on the slightly crumpled uniform. The thin white shirt would not be enough so he pulled on his grey school jersey – it was officially frowned upon to wear the jersey under your blazer, but even St Martins couldn’t stop people from trying to stay warm on cold mornings.

For the hundredth time John wondered why they would even have a school jersey if they had a problem with people wearing it. They’d only just stopped insisting that he wore shorts, so he took it as one of the many pointless injunctions that the school threw up. His mother said they were preparing him for the real world, which sounded about right, given how inconsistent and convoluted that appeared.

He fished some socks from the chest. He hadn’t realised how cold his feet were until he slipped them on and a tingling warmth made his feet ache. He stamped about a bit to restore the circulation.

Sharp morning light streamed through the hole at the back of the cave. His candle had burnt out during the night, but the glow of morning provided enough illumination for him to catch the trail of his breath steaming in the air.

Had it snowed?

If there was snow on the roads, it would slow him down and he had things to do before he got to school.

He had to hurry.

John snatched the watch from his workbench along with the repaired wind-up truck and slipped them into his battered leather satchel. He took one last look around the cave. Silver light poured through the thin crack. He narrowed his eyes and prepared to be dazzled, but there was little change in the diffused light as he hurried to the cave entrance – just mist in the hills.

John had to be careful not to be spotted – and the last thing he needed was to get muddy while squeezing himself between the rocks. He avoided marking his clothes too badly and was back on the road before anyone on the farm was awake to notice his passing.

As soon as he stepped from the cave, a weight seemed to bear down on him. Thin white vapours hung in the higher air, already melting before the sun. Below him a white cloak hugged the valley and twined tendrils around intermittent streetlights. Mist was a common sight at the crest of the hills around Dowdale but it rarely crept into the village, and for an instant John had a haunting impression of something let loose upon the valley. The silence of the scene throbbed in his ears. If he hadn’t been afraid of giving himself away, he would have yelled to break the sleepy spell around him.

Here and there Dowdale’s early risers shone their lights from behind frosted windows. It surprised John that he’d missed the signs of such a drastic change in the weather. The night before had not been warm, but it had been clear and pleasant enough; now the wind had teeth and the white shroud over the valley seemed a portent of increasingly bitter weather. John’s uncanny insights usually extended to predicting the weather. After all, what was weather if not another mechanism? If he’d been asked yesterday, he would have bet that the day was going to be sunny, but instead there were dark clouds massing up in the hills and a chill drizzle stung his cheek as he walked into town. Something in his gut told him that there had been a fundamental change while he slept, but what that might be he couldn’t begin to imagine.

I should have taken a raincoat. It was a practical thought and one that overrode any speculation about what malign forces might be working against him … It was all too easy to imagine that there was something out to get you when you were wet and cold – that was the kind of thinking Maribell favoured, and John knew better than to emulate his mother.

He let out a sigh. It didn’t matter what had caused the sudden change. If the weather had turned, he’d have no choice but to go home tonight. Not that he’d planned to stay out indefinitely – it just rankled to have to give up the freedom of being out on his own. He briefly considered slipping back into his room and getting another shirt. An image of Maribell still slumped against the door flashed through his mind.

She must have moved by now. But would she be herself again?

He told himself that his mother had got up and reverted to the more pleasant version of herself, but these days her fits seemed to last longer than they had when he was younger. John could remember a time when he’d watched her sit staring at a point in space for a whole afternoon. A fly had even crept over her lips, but she’d made no attempt to shoo it away. She’d sat there, her eyes dull, until he’d stopped trying to talk to her and had gone back to working on his repairs. Then she’d jerked upright shouting that the clinking of the music box was too loud. There were times it seemed that Maribell lived to yell at him, but there could be no doubting she cared for him too in her angry, selfish way. His mother’s life revolved around God, baking and him – the holy trinity.

John wondered what she did when he wasn’t there. She had to do something when she was alone; she couldn’t have spent her whole night leaning on his door. Maribell had her turns, but most of the time she was alright. She still went to church and attended village meetings. The citizens of the dale would not have put up with any strange behaviour for long, so she had to be alright when he wasn’t there to watch her, hadn’t she? So far as John could tell, no one else even realised she was broken. They didn’t see her the way he could. Did that imply that she had a choice about how she behaved? If she could hide so well from others, why did she take out her problems on him? Of course, it wasn’t that simple, no one else lived with her and as he’d got older, John had begun to realise that they had a strange effect on one another. He still couldn’t put his finger on it, but it was as if they were both tapping into something deeper that neither was prepared to acknowledge.

Perhaps my leaving the house was the best thing for her too.

The closer John got to his house, the heavier his guilt weighed. Despite his concern, he still made sure to turn down Rose and cross over to Dregan Street so he wouldn’t have to pass too close to the house. It wasn’t the first time he’d left his mother alone for a while. She would calm down, greet the neighbours, and everything would fall back into the same inevitable daily pattern. That made sense in his head, but when he looked down at the heavy vapours obscuring the road under his feet, John’s confidence melted.

He frowned. He couldn’t escape the feeling that something had shifted. It was like a smell that tickled the edge of perception, sharp enough to be noticed but too indistinct to be placed.

He turned at the last house on Dregan Street, and stared up at the church steeple thrusting through the dissipating morning haze. The sun rose behind it, throwing its long shadow at his feet like an accusation. John found himself remembering the first time his mother had dragged him to that church. She’d insisted that prayer would cure him, and in those days he’d believed her when she said he was sick. She’d made him kneel for more than an hour and by the time he’d got up, he’d known he wasn’t a good son; good sons did what their mothers told them and didn’t let the Devil use their hands.

That was a time before he’d seen his mother sitting motionless with a fly darting in and out of her mouth – he wondered what the congregants would have thought of their pious neighbour then.

The church had always made John feel uneasy. Maribell might call it a second home, but the place always smelt slightly stale to him: candles and damp, flame and water. It didn’t help that Maribell spoke as if the water in the font might start to boil at his very presence. John had always been made to feel like an outsider, whose salvation was a matter of patient sufferance. He didn’t know how many hours he’d sat on the thin, groaning benches when he was younger. He’d never encountered anything divine, but the drafty old church got cold enough to make you shiver and, if you were wearing shorts, the sticky varnish clung to your skin. The thin pages of the prayer books were grubby and felt like the wings of moths.

John didn’t go there now, not if he could help it. He knew too much about fixing things to believe in prayer. Religion certainly hadn’t helped Maribell; sometimes it seemed to make her worse, but then again there was no telling what she’d be without it. As much as he could wish for her to see the world a different way, John had begun to understand that it was better for his mother to have some focus than none at all.

John kept his head down as he passed the church, turning his collar to the poster on the glass doors – another cake sale – and the memories the building evoked. His school was three blocks away; he could see the yellow brickwork peeking over the row of store fronts that lined Elden Street. He’d made good time, despite the strange weather. John looked at his watch. He still had half an hour before the school day began, so he turned up Winchester and took a chance that John Beacham had risen early.

Most of the town was sleeping, but a light in the back of Beacham’s shop told John that he was in luck. He hurried over to the side entrance and knocked politely. There was a faint scraping and rustling inside – Beacham was a slow and deliberate man, who never did anything in a rush. He was one of the few adults in Dowdale John respected. After a protracted series of clicks, punctuated by the jingling of keys, the door opened and John’s patience was rewarded with the sight of his older friend. The shop owner’s salt-and-pepper hair was slightly awry and his teeth were clamped on the stem of a pipe that John had only once seen him light. Mr Beacham looked as tired as John felt, but that was to be expected – his line of work meant he kept similar hours.

“Ah, John,” Beacham said.

“John,” John replied. Their shared name was a joke between them, but it wasn’t all they had in common. Mr Beacham also had a love for old things, and his shop was a treasure trove of venerable wonders. In recent years, Mr Beacham had even trusted John to restore some of his merchandise. He took one look at the watch John was holding up for him and smiled.

“I’d tell you it’s a bit early, but I see you come bearing gifts.” The shop owner stood to one side so that John could enter if he wished.

“I thought it would be best to give them to you before school starts,” John said.

Mr Beacham frowned, but he was diplomatic enough to let the statement pass. It didn’t need restating that John simply wasn’t big enough to protect anything he brought with him to school. It had been less than six months since Andy Burne had torn the arms off a toy monkey that John had been restoring for the shop. The boy had been sure that Mr Beacham would be furious – and he was, but not with John. John had barely managed to persuade his friend not to contact Andy’s parents. On the one hand John was grateful that anyone cared enough to want to fight on his behalf, but he knew that nothing good would come of telling on the other children. Things were hard enough as it was. As Mr Beacham had commented at the time, talent can have a strange effect on those who do not share it, and John had learnt that it was better to go unnoticed. Of course, there was only so much he could do to avoid being bothered – everyone knew that his school bag was often worth rifling.

John crossed to one of the benches and tugged the repaired items from his bag.

“Good job, as always,” Mr Beacham said. “The watch might fetch a good price. Can’t give you much for the toy, I’m afraid.” Mr Beacham didn’t just enjoy fixing things – he had a taste for haggling that he fruitlessly tried to encourage in his young protégé.

John nodded amiably. “Whatever you think they’re worth.” He set down the items on Mr Beacham’s desk and cast his eyes over the stock in the back room while Mr Beacham appraised the watch.

“The hands aren’t original, I see. Good choice for the replacements, though,” the shopkeeper mumbled to himself.

John’s gaze alighted on a heavy old Swiss army knife. “How about a trade?” he asked.

The shopkeeper looked up. “Oh, you noticed that, did you? Thought it looked like your kind of thing. One of the blades is broken, though. That’s why I didn’t put it in the front.”

John grinned. He knew very well that Mr Beacham could have sold the penknife, broken blade or no broken blade. “Thanks for thinking of me. Mind if I take a look?”

Mr Beacham returned his smile. “Of course, but it’s that or the money.”

John picked up the old knife; it was surprisingly heavy. He unfolded a blade, a saw, a corkscrew and a screwdriver. He could imagine a hundred uses for each new protrusion. “It’s only the little blade missing,” he said at last. “I’ll take it.”

Mr Beacham winked. “I thought you might. I don’t need to tell you to be careful with it, do I?”

John rolled his eyes. “Of course not.”

“It never hurts to be reminded.” Mr Beacham’s face dropped slightly. “And the other … problem?” There was a pause as he struggled to find a delicate way to put things. “You won’t let the other kids take it from you? I don’t need something silly happening and people blaming me.”

John grinned, flicked open his school bag and teased open a small leather pocket that he’d worked into its inner lining. “I’ll make sure it’s safe,” he promised.

If you didn’t know to look for the hidden compartment it would have been surprisingly difficult to find.

Mr Beacham raised an eyebrow. “Fancy work. I’m sure I’ve got some leather in the front that could use that kind of touch.”

“That’ll cost you more than an old pen knife,” John shot back.

The older man chuckled. “That’s the spirit. We’ll make a haggler out of you yet.”

“Not something a shopkeeper should be looking for in a supplier,” John observed. He closed his bag and slipped the strap over his shoulder.

Mr Beacham shrugged. “Nothing wrong with a fair bargain for both sides. Cheap work’s cheaply made more often than not.” His eyes narrowed. “Besides, play your cards right and one day I might be looking for a business partner.”

John’s eyes widened. He’d never doubted that Beacham respected his work, but he’d not expected to hear an offer like that. His friend’s comment sounded more than half like a joke, but the possibility still stunned him. What would it be like to have a shop of his own, a place where he could restore and fix things, maybe even work on original designs? It was a beautiful thought but it dissipated quickly – all he’d ever imagined was to get beyond the town he’d grown up in, to see the world beyond Dowdale.

The shopkeeper filled the silence with a cough. “Looks like you’re sorted then. Go well, it’s been a pleasure doing …” Beacham glanced away at a sound from outside, and his face soured as he stared out into the street. “Can I help you?” he asked, his voice suddenly cold.

John caught a glimpse of a shadow stretching past the half-open door. He heard a low murmur and a scrape on the stair. He instinctively stepped out of sight, but his heart leapt as the hinges began to creak and the door opened towards him. John didn’t know why he was afraid, but he was sure he did not want to be seen by whoever was on the step outside. He edged back as his hiding place slowly shrunk. At the last instant Mr Beacham stepped across the room and took a firm grip on the door.

“If you want anything, I’m afraid you will have to go to the front entrance. I’ll be opening in ten minutes.”

John leant closer to the door. Despite his proximity, he could not make out exactly what the person outside said in response. It was a man’s voice, raw and gravelly, but pitched so that the words seemed to flow into each other, familiar yet indistinct. Like hearing someone speak another language, but recognising every fifth word.

But the stranger’s request seemed clear enough to Mr Beacham. He nodded his head in a peculiar way and replied, “No. I don’t do business with the travellers any more.” His voice seemed thick and weary, but it sharpened as he added, “And I don’t want anything to do with the likes of you.”

The low rumble of the man’s response was still hard to interpret, but it clearly didn’t please Mr Beacham. He frowned and raised his hand to rub his brow, just as the door began to creep open again. John flattened himself against the wall. Mr Beacham snatched the handle, but even that much movement appeared to cost him – he looked as though he was rooted to the spot, the muscles of his face twitching in pain or outrage. It reminded John of when his mother had one of her turns.

John leant even closer to try and hear what was being said. He felt a low vibration in the wood touching his cheek and realised that Mr Beacham’s knuckles were white with pressure, his arm quivering as if the door weighed so much he could barely hold it.

John was suddenly certain there was no way Mr Beacham could stop the door from opening all the way. He would be seen and when he was …

Rex, the shop cat, slunk into the room and gave an angry yowl at whoever was in the street. Under normal circumstances Rex would never get on the workbenches or disturb one of Mr Beacham’s projects. The relationship between Rex and the store owner would not have been a long one if Rex were prone to high levels of feline skulduggery, but the cat upset more than one of Mr Beacham’s personal projects as he leapt onto one of the tables and went barrelling back into the front of the shop.

The sudden noise seemed to break whatever malaise had gripped Mr Beacham. The shopkeeper shook his head slightly as if trying to clear it, before he spoke again. “Please leave. As I’ve already told you, we are not open yet.”

There was a strange, almost plaintive whine in Mr Beacham’s voice. John had known the man a long time and he’d never heard him sound like that – vulnerable and uncertain.

Who or what could make Mr Beacham afraid in his own shop?

The gravelly voice sounded once more and John heard feet shifting on the step outside. For one terrible moment he thought that the door would be torn from Beacham’s hand and whoever was on the other side would rush in. Then the footsteps began to retreat.

John screwed up his courage and dared to peek round the door. A fleeting glimpse of a dark coat and a flash of white, waving hair that seemed to blend with the thickening mist. Then the stranger was swallowed entirely.

“John, get back I say!” There was no mistaking the panic in Beacham’s voice.

John turned to his friend in shock.

Mr Beacham looked embarrassed. “Sorry, I was about to close the door. I thought I might catch you.” They both knew that was nonsense, but neither wanted to prolong the weirdness of the situation. John stepped back. The door stayed open.

“Mr Beacham?”

The man didn’t respond.

“Who was that? What did he want?”

“Hmmm.” Beacham was a thousand miles away.

“I said, who was that? And what did they want from you?” John repeated.

“You mean you didn’t hear? But he was so loud, so …” The shopkeeper trailed off. Then he blinked and took a slow breath. “He was no one important, just a tramp. Only wanted to know the time is all. Speaking of which, I hope you set that watch you sold me right, because I reckon you’ll be late for school.”

John looked down the road, where the mist was retreating before the sun. Then he glanced at his wrist and blanched. The interaction between Mr Beacham and the stranger hadn’t seemed very long, yet he didn’t have a moment to spare.

“You’re right – I have to go, Mr Beacham. Miss Collins makes a note of tardiness and I don’t want her telling my mother.”

Not that there was any way Miss Collins could phone.

“No, we wouldn’t want that.” Beacham still sounded distracted and John had the suspicion that his first customers would find the shopkeeper strangely out of sorts. John gave his friend an appraising look, but Mr Beacham grinned back as if everything was fine.

“You’re sure you’ll be okay?” John asked. “You don’t think the tramp will come back, do you?”

Mr Beacham seemed not to hear him. “Okay, John, you’d best hurry; keep that knife safe.” He went back to examining his new acquisitions. “You make sure the other kids don’t find it. You’ve somewhere better than your pocket to hide it, right?” Beacham added as an afterthought.

John frowned. “But I just showed you …”

Mr Beacham’s brow wrinkled and he looked like he might say something, then he let out a sigh. “You still here, John? You’d best be going.”

There seemed little point in going over the event that had just passed – John’s instincts told him that would only cause his friend more distress. But it left John wondering exactly what he had witnessed.

The talk of Mr Beacham doing business with the travellers had piqued John’s curiosity, but not enough that he wanted to meet the man from the mist face to face.

“Okay.” John tried his best to pretend that everything was normal, and even stopped to wave goodbye when he saw Mr Beacham staring down the road after him. But the shopkeeper was too focused on some point in the distance to respond.

John wondered about the stranger as he walked the three blocks to school. He’d never seen his friend act anything like that before, and he had to wonder if his apparent disorientation had been genuine or merely designed to deflect questions. Was it possible the two men knew each other? John imagined that the “tramp”, as Mr Beacham had called him, was some long-lost relative. Or perhaps a slighted business partner.

What was Mr Beacham hiding?

John couldn’t imagine that the older man would have such a strange reaction to a tramp. There had to be something more to it – but did he really want to know what that was?

The school gates were in sight when a strong hand grasped his shoulder and tugged him back into the shadows of Aden Alley. John stifled his cry of surprise when he recognised it was his mother towering over him.

“I told them you were sick, John,” Maribell hissed. “And that isn’t so far from the truth, is it?”

Tears welled at the corner of John’s eyes as her grip tightened and his collarbone began to take strain. He refused to let her see how scared he was. All thoughts of Mr Beacham had disappeared; his focus was entirely on his mother’s contorting features.

“What are you doing here, Mum?” John didn’t like what he saw in her eyes. The night had not appeared to calm her.

“What am I doin’ here?” She dragged him up by his shoulder. “What are you doin’ here? Why weren’t you at home this morning?”

“I’m going to school, Mum, and then I was going to come straight home, honest.”

Maribell snorted. “Honest? You must think I’m thick as wallpaper paste.” Her lip twitched. “But don’t worry, I told them you were very ill, so you don’t need to go to school today. Not today and not tomorrow.”

“Tomorrow’s Saturday,” he reminded her. The protest earned him another painful squeeze.

“Well, who needs to go to school when they’re as clever as you, Mr Smarty Pants.” She shook him and the back of his head skimmed the rough brickwork of the wall behind him. “You aren’t going in Monday neither. Not going to make a liar out of your mother, are you?” Her eyes narrowed. “I could make it so you had to stay away for a very long time … and what would you do then? I know you like tellin’em about me, John. You fixed the phone, didn’t you? You brought them into our lives with their stupid tests. You brought the Devil right into our home.”

John tried to pull free, but his mother’s grip was firm.

“Oh no, there’s no slippin’ away now. You can’t just go where you like whenever you want to. Even your school would agree with that.”

“What are you talking about? I’m trying to get to school and you’re stopping me. Let me go, Mum, and we’ll talk –”

“I’m your mother, John,” Maribell cut him off. “Do you really think you can ignore me? Sneak off, and I won’t know?”

John wanted to say, You were too busy staring into thin air to notice the last time, but instead he ducked his head and tried to make himself as small as he could – fervently hoping that this storm would pass.

His mother drew him closer, and he could hear her frantic breaths rasping in her huge chest. She was still in the same clothes she’d been wearing the day before, and there was an unpleasant sharpness under the cheap, familiar scent of synthesised lavender.

“How many times do I have to tell you, John? You were never meant to be part of their world. You have to stay with me … It’s the only way we will both be safe.”

Maribell’s eyes became unfocused, then swept down to follow the faint tracks of mud across John’s jersey.

“I won’t have you embarrassing me neither,” she snarled. “Look at the state of you. Go home and get cleaned up. You’re not going anywhere lookin’ like that. Not where people know me, and not to some high-and-mighty school that thinks the sun shines out of your britches.” She laughed. “Not that they’d even take a sorry excuse like you. Look at you! You look like you spent the night in a bush.” Maribell fished about in her cleavage and brought forth an old handkerchief. She spat on it and rubbed it across his face.

John squirmed but she ignored his resistance.

“I don’t know where you’ve been, John boy, but you scared me half to death.” She gave him an appraising look but then snarled at his lack of response, and carried on scrubbing. “Up to no good, I’ll bet. Getting filthy and shamin’ me in front of everyone. The Devil may have got you this far, but I promise you aren’t going no further.”

John fended off most of her matronly dabbing and did his best to square his shoulders against her iron grip.

“I didn’t do anything,” John protested. “How could I know what they were calling about? They told me to take the tests and –”

“And you did and the Devil gave you the answers, like he told you to fix that phone. Don’t be fooled, John, nothin’ happens by accident and there are things out there just waitin’ to get their hooks into a young boy like you. Demons, John, and you’re callin’ them to us.”

John tried to peer past his mother to see if anyone had noticed them. Maribell seemed past caring, or she’d blame the forces she said were constantly trying to undermine her, but John knew there could be trouble if they made a scene. If the wrong person saw her acting crazy like this, Maribell might be taken away and John would go to some foster home. It was a fear he’d harboured all his life, one his mother had built into him with her talk of demons and devils coming to take him away. John took the pain and kept quiet. He’d endure this, for both their sakes.

“I know the real trouble, John. You’re faithless, just like your father. He left and he left you his taint. I see it in you every day, and there’s no gettin’ it out.” She gave his face another vicious wipe, as if she could scrape away the wickedness she saw in him, along with the memory of a father he’d never known.

“I didn’t leave … I got scared … I didn’t mean –” John struggled to find the words to diffuse his mother’s anger. Love and fear are a volatile mix and he lurched between the two as he stared into his manic mother’s face.

“Oh, they never mean to, not one of those sinners that writhe beneath us wanted to fall, John. They all had reasons and the very best intentions, they all thought they walked in the light, but that’s just when the Devil gets you, John – when you’re not lookin’ for ’im!”

Tears pooled at the corner of John’s eyes. “Mum, please.”

Maribell ploughed on. “What did the people from that fancy school want if not to take you away, eh?”

Flecks of spittle landed on John’s face. It was impossible to pretend that he wasn’t in danger. What if he called for help and no one came? Maribell would only get madder and he’d be all alone in the face of her rage. John slumped in his mother’s grip. He wasn’t strong enough to break free.

“Don’t think I’m stupid, Jonathan. You think they would have just called and offered you a scholarship if you hadn’t done somethin’ to make them? Hmm?” She prodded him painfully in the chest with a finger.

“I … I don’t know.”

John’s mind went back a few weeks. Miss Dunar had asked him to take that extra test; she hadn’t said what it was for. Miss Dunar and Maribell had never got along … Miss Dunar was the sort of person who would try to help him even if he didn’t want her to. She was also the sort of person who would ensure that he never saw his mother again and even after everything, John didn’t want that – not yet.

“I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to cause any trouble. I just did what I was told,” John’s voice cracked; he was only half putting it on.

Maribell shook him again. “Don’t you try those crocodile tears on me, young man. It’s you that got us into this.”

He sniffed and nodded. “Sorry.” He wasn’t, but what else could he say? If he could calm her down, maybe she’d forget and go back to normal.

Her face softened slightly. “That’s better. The first step in salvation is knowin’ you need to be saved.”

There was no point in fighting; his only remaining weapon was surrender. “Yes.”

Maribell looked around, suddenly aware of where they were. When she was satisfied that no one was paying them any attention, she leant closer.

“Here’s what’s goin’ to happen: you’re going to be sick for the next week, John. You stay away from here and those degenerates. Maybe this will all blow over and we can go back to the way things were.” She gave him a sheepish smile. “You understand, don’t you? We can’t let them break us apart.” She enfolded him in strong arms and John felt the wooden handle of her basket dig into his back. “You wouldn’t leave me, would you, John?”

Resentment mingled with affection for the woman who had both shielded and confined him all his life. When he’d been younger and they’d had this sort of confrontation, Maribell had been very good at making him feel like it was the two of them against the world, that her rage had been necessary and justified in the defence of their family. Now he was older it wasn’t so easy to accept the picture Maribell was trying to paint. She was the bully, not the world, and it sickened him that he still wanted to believe in her.

“Of course I won’t leave you, Mum. But I do need to go to school,” John said. “If I don’t turn up, they’ll just ask more questions.”

Maribell stiffened and her eyes narrowed. John waited for a moment for his mother to relent and then tried to push past her.

For an instant, he thought he was free. Then her grip tightened and she stepped back so that she was holding him at arm’s length. Her broad face was lined, her eyes were red, and John could almost believe it was she who was cornered and hunted.

“I thought you were supposed to be smart, John. You can’t go into school today – I already told them you are sick. I won’t be made a liar. The only place you’re goin’ today is back to the house. You’re goin’ to clean yourself up and you’re goin’ to wait for me to get back from church. I’ll pray on what we should do next.”

John gritted his teeth. If he was smart, he’d do as she said, but he found it wasn’t that easy to let her have her way this time. “You can’t just stop me going to school,” he said. “I’m sorry I messed with the phone, but you can’t keep me locked up at home.”

What exactly had she told the school?

It was frighteningly easy to imagine what might happen if Maribell succeeded in cutting him off from everyone he knew. Again he pushed hard against her grip. To his surprise, Maribell let him go and took a prim grip on her basket of muffins.

“Have it your way, John. Go if you must. Smear my name and speak to the wicked people from that fancy school. Just know I’ll be waitin’ for you at home, John. Waitin’ and prayin’.”

John glanced at the school gates, then back to his mother. He still felt guilty, even through his defiance. His father had walked away, and now he was walking too. It didn’t matter that she was pushing him – when he left he’d be no better than the man who had gone without him.

On the other side of the wall John could hear the first cries of his fellows coming in from the second gate. It wouldn’t be long before others started arriving from this side of town. It was tempting to wait and let himself be seen, then things would be out of his hands.

He took a step towards the school. His mother looked at him, daring him to make a liar of her and see where that got him.

John’s shoulders slumped. The hope that someone might come along to save him was futile. All anyone would see was a child arguing with his mother, and Maribell knew it. It was, John thought as he hefted his bag and strode off in the direction of home, one more isolated battle in a very lonely war.