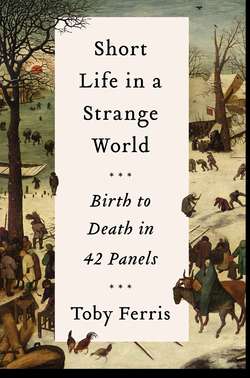

Читать книгу Short Life in a Strange World: Birth to Death in 42 Panels - Toby Ferris - Страница 13

III Fire

ОглавлениеAntwerp and Rotterdam (6.316%)

‘The air still moves, and by its moving cleareth, The fire up ascends, and planets feedeth.’

Fulke Greville, Caelica

Months pass, and I wage a phoney war against the looming Bruegel Object, pick off a panel here or there, drag myself like a forlorn expedition over the still-featureless map of all Bruegel. Finding landmarks.

The cities I visit are cities named in a dream of Europe. Rotterdam. Antwerp. Places you might struggle to put a pin in, but which underlie your notion of European. Once I have visited them, I hardly know that I have been there: waystages on a cosmic map.

Rotterdam, for instance. Rotterdam is a station, roadworks, new buildings, a long straight walk to the museum along a windy street. It is a museum built in the 1970s, an empty café with coloured chairs.

That is Rotterdam. Have I been there? Barely.

*

I am in Rotterdam with a friend, a painter called Anna Keen. Sister of Zabdi, my paragliding instructor. In Rome in the 1990s we were a couple. We lived behind the Colosseum on top of the Domus Aurea, Nero’s cavernous, mouldy, buried golden palace, with its revolving dining room and its obscene frescos.

Now Anna lives in Amsterdam, in a shed near the water, and I am paying a visit. In a couple of days my brother will join us.

The shed is part of a complex of work units – next door, for example, is a builder of speedboats, or racing yachts, I do not remember which. I only remember looking down the length of streamlined hulls, bright paintwork, varnish. Rigging? I don’t recall.

Anna’s shed is also her home and a source of income – she sublets parts of it as studio and living space to art students. Her brother Nick, a carpenter, has come over for a few days and built partition walls. Anna lives upstairs in the low-ceilinged loft that runs the length of the shed. You have to stoop as you walk along it. You ascend by a ladder between two antique electrostatic speakers into her wonky space of two thousand books and paint-stained electronics – laptop, router, amplifier, speakers – and naked plasterboard. A padded silver pipe runs up through the floor. Plastic flapping windows give on to the main space, where Anna has her own wooden boat propped up and her immense easel, and endless red-and-white packets of a line of budget food called Euro Shopper which for some reason she cannot stop buying, and presumably consuming, and wants to paint. On each packet is a schematic drawing indicating the packet’s contents – a red-and-white cow (milk), a red-and-white peanut (peanut butter), a red-and-white gravy boat (brown sauce), a red-and-white whisk (whipping cream, UHT). They are everywhere. A ready-made Warholian homogenization of all food and all household goods, in this most dehomogenized of spaces.

Anna has installed a large wood-burning stove in her kitchen, and it directs heat around the shed complex along silver-insulated pipes. It is February, the stove is working full time, and everything you touch is either scalding hot or icy. The inhabitants of the shed (three, four art students, Anna, Anna’s brother, Anna’s brother’s girlfriend, my brother, and me) shuffle around wrapped in scarfs and old jumpers, clutching mugs of tea, seeing how close we can get to the fiery stove without singeing our flesh. Whatever the stove radiates seems to dissipate within an inch or two of its cast iron: the zone of warmth is perilous and narrow.

I persuade Anna to come to Rotterdam and look at the Bruegel.

Rotterdam. To recapitulate: a station, a street, a museum, the wind, and The Tower of Babel.

Museums are for the most part horizontal structures. I do not know many properly vertical museums. But the Rotterdam museum contains one of the great essays in verticality. It is the smaller of Bruegel’s two Babel panels – the other hangs in Vienna – but the larger of the two towers. The compositions are similar. The Vienna tower is built around a cankerous rock and in the foreground, receiving obeisance from his stonemasons, there is a king (Flavius Josephus ascribed the building of the tower to Nimrod); the ships are much larger than those in the Rotterdam panel, the horizon subtly higher; in Rotterdam we are higher, therefore, and see further.

Essays in verticality: The Tower of Babel – Vienna (top) and Rotterdam (bottom).

The rocky outcrop jutting from the Vienna tower is not the foundation but the metamorphosis of the built structure – there can have been no pre-existing plugs of rock on this flat plain. The weight of the tower has compressed and transformed its materials. It is subsiding on the shore side into marshy land.

The Rotterdam panel, on the other hand, is a pure geometry. Lessons have been learned. The only transmutation of materials here is into upthrusting energies. No wonder the builders’ jealous god got worried.

Both towers not only dominate their respective landscapes: they are the landscape. Everything of interest on the nondescript plains is subsumed into the towers, just as a great city – Antwerp, for instance, or Brussels – will suck economic energy from the land and the seas which surround it.

Bruegel was an inheritor of the Netherlandish tradition of the World Landscape – painters such as Herri met de Bles and Joachim Patinir had for a generation before Bruegel produced increasingly broad and schematic landscapes where great rivers and mountains and plunging precipitate views and cliffs and oceans beyond stood as much for a representation of the cosmos as for anything you might see in nature.

Landscape started to emerge from the background, took a sociological, topological, cartographical, thematic turn. It became not just a reflection of cosmic order but the whole theatre of man and his salvation, the teatrum mundi, the theatre of the world.

Bruegel introduced a note of difference, however. A naturalism. Simon Schama observes that, relative to the work of Patinir and met de Bles, the landscapes of the early seventeenth century had been ‘deprogrammed’. They had ceased to be grand schematics of the cosmos, or moral topographies, and were now ‘just’ trees, woods, streams. And this process of deprogramming begins with Bruegel.

In around 1552, Bruegel, a young painter newly emerged from his apprenticeship, travelled to Italy, most likely with fellow painter Maarten de Vos and the sculptor Jacob Jonghelinck. He travelled down through France (we know of a lost gouache View of Lyon); proceeded over the Alps to Rome, where he stayed for two years; and then pressed on more briefly to Naples, Reggio Calabria, and in all likelihood Sicily.

Such a trip was not unusual for ambitious Northern painters, who were expected to educate themselves in the ruins of classical antiquity and the works of the Italian Renaissance masters. Bruegel most likely did precisely that but, perhaps at the instigation of the Antwerp printer Hieronymus Cock, he also documented his trip with reams of topological views: the Bay of Naples, Reggio Calabria, the Strait of Messina, Rome, the Alps. And on his return, it was with these views and a set of generic engravings – the so-called Large Landscapes, incorporating elements of his Alpine journey – that the young Bruegel established his reputation. ‘On his travels,’ wrote Van Mander, ‘he drew many views from life so that it is said that when he was in the Alps he swallowed all those mountains and rocks which, upon returning home, he spat out again on to canvases and panels.’

Bruegel had a precise eye. His work has been described as ‘ethnographic’, so fastidious is it with details of peasant life, and in the same way his World Landscapes never neglect shape of leaf or jizz of flying bird – a generic silhouette in the sky is, on closer inspection, a magpie or a cormorant; a foreground plant is not just an iris but an Iris germanica. The natural world adorns the schematic landscape, or the schematic landscape polarizes the naturalistic detail, in a way that Ruisdael or Hobbema, or Constable or Monet, would have understood. The real keeps impinging on the meaningfully arranged. And vice versa. We are caught in suspension between what God ordains and what Bruegel experiences. And the two are not necessarily aligned.

On his Italian journey, Bruegel must have seen and drawn, and, to judge from his versions of Babel, slightly obsessed over, the Colosseum. Both the Rotterdam tower and the Vienna tower are colosseums telescoping upward to infinity. Both are set on the plain. There are some distant hills in the Vienna panel, none in the Rotterdam panel. To repeat, both towers are the landscape, translations of the cosmic landscape into urban form. These are stone cities pulled up from the earth in the manner of origami trees, birthing strange rocks, over-topping the clouds, bending the frame of the earth. Symbolic, but also detailed. Naturalistic.

The Rotterdam tower – the later of the two, by some five years – is both an architectural and a chromatic fantasy.

At the top, the endless intricacy of its internal form is revealed. The Gothic variation and repetition of its windows and arches makes of them not merely entrances but a sort of hyperbolic internal structure, as though the builders had lighted on some multidimensional or geodesic solution to the incalculable stone weight of the structure that had defeated them in the Vienna panel; this fresh tower will go up and up supporting its own weight on tensile Gothic arches and windows.

Pollen of the mason’s art: The Tower of Babel (Rotterdam), detail.

There is no king here, no central intelligence and motive force. The builders of this monstrous beautiful thing scurry over its exterior and interior like the manifestation of an algorithm, working their twig-like cranes and filigree hoists, leaving deposits on the pinkish sandstone of white and red from where the marble dust and brick dust are shaken like chalks, pollen of the mason’s art.

*

At the base of both towers are culverts or sally ports where a boat might drift inside, sail right into the heart of the endlessly ramifying structure. You might load your ship with barrels of gunpowder and seek out the keystone, the arch or spar whose destruction would bring the whole of this tyranny crashing down. Every project has its point of weakness. A niggle, a suspicion, a discord. If there were not, there would be no need for a project. Straight life would suffice. The project is an attempt to reconcile irreconcilables, to square the circle. Something must be fudged in the process.

Freedoms, for instance. Manfred Sellink, cataloguer of Bruegel, finds the Rotterdam tower more menacing than the Vienna; the equally eminent Larry Silver regards it as an index of the productive capability of a free people (the Netherlanders) contrasted with the crooked construction of a subjugated slave race (the Spanish).

I do not know whether the tower is menacing or not. It is certainly fascinating. Did Bruegel have the ways of tyranny on his mind? It seems obvious to us – his Netherlands were part of the Habsburg Empire, effectively under Spanish rule. In his lifetime its people would start to resist, and, just months before his death, rebel.

Why else, after all, would you paint the Tower of Babel again and again (and again – there is documentary evidence of a third version from his Rome years, on ivory, now lost)? Who knows? The Colosseum must have made its impression on a young visual mind, its self-similarity, its modularity, its controlled barbarity. The Tower of Babel in the biblical sources represents hubris and fragmentation, but it also stands on the last edge of a unified world, one sufficiently sure of itself to embark on a grandiose building project. Bruegel’s contemporary and friend in Antwerp, the printer Christophe Plantin, would in the last year of Bruegel’s life begin setting his great bible, the Antwerp Polyglot, in five languages, Hebrew, Greek, Latin, Aramaic and Syriac, with dictionaries and grammars, itself a monument to clarity in fragmentation – as though bringing all these languages together in one huge volume under a sufficient weight of scholarship might metamorphose the sedimentation of scripture into a solid impregnable rock.

Tower, Empire, Bible: grown sufficiently tall, sufficiently all-encompassing, sufficiently all-explaining, they become like the earth itself: inescapable, eternal, boundless.

What lies under the eye of God and eternity? Great landscapes and towers, and tiny people.

On the fourth spiral of the Rotterdam tower, very close to the mid-point of the panel, you can make out, if you crane in close, very close, and stare hard (with your god-like eye), a tiny procession with, at its centre, a red baldachin. Under this, it has been suggested, a pope is making his ascent of the tower. Roman colosseum, pope at Rome, tyrannical Spanish inquisitors. Draw your conclusions.

A society on the brink of revolution, or lying under the yoke of tyranny, grows cryptic. Things are necessarily hidden. We have no way of knowing where Bruegel’s sympathies lay. All we know is that his compositional instinct veered towards crypsis: hide the subject.

*

I am beginning to get a feel for the Bruegel map. An outsider’s feel. The feel of an autodidact.

The Bruegel tower in Rotterdam is a pin. I can wind a string around it, stretch it over to Vienna and wind it again.

I still do not know, in Rotterdam, that I will see them all, that this is my project, so the map of all Bruegel remains at this point mostly featureless, speculative, a land of hearsay. I know that there are plenty in Vienna; others are in Madrid, Paris, London, New York. I have looked at the Bruegel page on Wikipedia, and have promised myself a book on Bruegel. But which one? Another unknown landscape stretches out before me, of Bruegel scholarship.

It will be by no means my first project. I have spent half a lifetime working up projects: Robinson Crusoe canoes, antique flying machines that never fly. All useless devices, but each informed by the same creative spurt, each one a new, futile form of flight, of escape. Just like that tower on the plain, on the edge of the sea, fugitive city making for the skies.

In the early 1950s my father and a friend of his called Bill (surname unrecorded) booked themselves on to a coach tour of the Low Countries: Bruges, Ghent, Brussels, Antwerp, Amsterdam. But the authority of their guide, the tyranny of the schedule, the sluggishness of the coach immediately chafed, and they abandoned the tour and took themselves off on a mad jaunt of their own devising: church, bar, red-light district. My father still talked of it half a century later (although he glossed over the red-light districts; I learnt about these after he died, from a notebook he kept). The trip was, for the rest of his life, a reminder of the exultations to be had from torching the programme and careening off the map.

I have known similar moments of minor exultation. For example, I have walked out of more jobs than most people have had jobs.

Things change, one moment to the next. One moment you are employed, seemingly reliable, a plodder; the next you are enjoying some sort of giddy breakdown.

The last time I walked out of a job, my first son was not yet one year old. This is not responsible behaviour. After a few months, I ended up on my feet, again, just, but this had to be the last time. I have tried revolution. The knucklebones are just knucklebones, in the end, and the patterns are always familiar. Perhaps I did not burn deep enough, early enough; perhaps I should also have salted the black fields of my existence. But the suspicion remains: there might be other ways to model your life.

On our return from Amsterdam, my brother and I run into difficulties. We have chosen to take the train so that we can stop for a few hours in the Brussels museum and refresh ourselves with Bruegel, but the train lines are down at some key junction. We wait for an hour on a cold platform with Styrofoam coffees, then take a train to the next stop down the line – The Hague. We have to get off. No one knows what is happening. We are told to get on a certain train, which takes us to the next stop – Rotterdam. And we have to get off again. Thus it continues, all day: we work our way from Amsterdam to Brussels one stop at a time.

Bruegel did not live in a world of timetables. Deadlines? Highly doubtful, although I can at least imagine a time-is-money Hieronymus Cock goading on his young artist, clapping his hands together in a show of energy, dividing up the labour, watching his costs. I can also imagine his young artist, possessed of a peasant’s appreciation of his own value, resisting, taking his time, not so much doing as getting around to.

We live otherwise. We must get back to England today. At each stop, when it seems we have finally run out of luck, my brother and I furiously google alternative planes, buses, but then before we can act a train turns up and there is a frantic cramming to get aboard. Dordrecht. Roosendaal. Antwerp. It grows late. Dark. We miss our connection in Brussels. And we miss the Bruegels. In the thick press of quantified time, all spears of purpose are, sooner or later, shivered.

I have a superstition about travel: it has a prevailing wind. If you make a there-and-back-again journey, you will be swept along easily in one direction, and have to beat back painfully in the other. But this is more than an ordinary squall or countervailing trades: it is clear to me now that we have offended the Netherland Poseidon. We have treated his realm as one entity, a large flat land with a common language, dotted with emblematic Bruegels. But it is not. It is fractured: by language, by politics, by religion, by river and sea, by the repelling magnetic North–South grain. And so we are smashed this way and that.

*

In 1566, called by contemporaries the Wonderyear, the Netherlands, North and South, were host to a spate of image-breaking. Churches were sacked, statues and paintings smashed, pulled down and burned, and the consecrated host, which renegade hedge-preachers called ‘the baked god’, was generally humiliated.

Some of the hedge-preachers – so-called because they preached outside the town and beyond the reach of civic jurisdictions – were Calvinist ministers who had returned after the suspension of the Inquisition in the Netherlands by the regent Margaret of Parma in April of that year; others were disgruntled ex-monks jumping the walls. They preached reform, and they preached iconoclasm, and in August, starting on the 10th in the town of Steenvoorde in the industrialized Westerkwartier of Flanders, some made good on their preaching by leading a mob to the chapel and sacking its images.

The violence spread, reaching Ypres on the 15th, Antwerp on the 20th, Ghent on the 22nd, Tournai on the 23rd and Valenciennes on the 24th. In Antwerp, the Feast of the Assumption on the 15th passed off peacefully with a parade of a statue of the Virgin, but on the 19th a group of youths entered the church where it was housed and mocked it. They were dispersed, but returned on the 20th accompanied by half the town. After some psalm singing, the church was sacked, with the rioters parading in the vestments, drinking the holy wine, and bathing their feet in the holy oil. In Ghent, the image-breaking extended to mutilation, mock-torture and mock-execution of statues and paintings. The great Van Eyck altarpiece Het Lam Gods was only saved by being hastily disassembled and concealed in a locked tower of the church under guard, while the iconoclasts went about their business below.

For the most part, and in contrast to the iconoclasms elsewhere in Europe (France, Switzerland, England), the procedure was genial, carnivalesque and often very orderly, a holiday from incense and mummery. Through August and September, the hedge-preachers moved in to some of the now cleansed churches, cities were barricaded against the often complicit local authorities, independence declared. But the Spanish clamped down. Early in 1567 the Duke of Alba arrived from over the Alps with armies and siege trains, and the uncoordinated fires of rebellions were extinguished one by one.

By 1566, Bruegel had left Antwerp for Brussels, a distance of 30 miles, exchanging the commercial capital of the Spanish Netherlands for the political.

His birthplace is usually given as Breda (c.1525) or environs, but he seems to have grown to artistic maturity in Antwerp. It is supposed that he settled there after his return from Italy in 1554, although there is no documentary evidence. However, his early artistic endeavours were all drawings for engravings for Antwerp print houses (notably, the Sign of the Four Winds, run by Hieronymus Cock). His first surviving painting, which hangs in San Diego, dates from 1557, but only a handful of paintings were made before 1561. It was from 1562 that painting really took over. By 1563 he had settled in Brussels and married Mayken Coecke, daughter of his master, Pieter Coecke van Aelst, and the miniaturist Mayken Verhulst; Van Mander has Mayken Verhulst persuading Bruegel to settle in Antwerp in order to distance himself from a previous amour, a serving girl he wanted to marry but found to be a serial liar. In Brussels, Bruegel ran a small workshop (where, according to Van Mander, he delighted in spooking his assistants and pupils with ghostly noises), although there is little if any evidence of workshop hands in his painting (some have taken the sky in the Census, for example, that lurid sun and the flattened treetop through which it shines, to be by assistants). From 1562 Bruegel painted an average of five (surviving) panels or canvases per year, until 1568, the year before he died, implying that he must have died early in 1569.

And so there he is, Bruegel the Elder: a creature of paint and prints, of signatures and hearsay. Nothing more now.

The documentary evidence for my father’s life is similarly scant, if methodical. I have, for instance, a small stack of his notebooks, maintained over seventy years. Five, in total. As follows:

1 A discoloured brown notebook, Where Is It? printed in black across its cover, in which my father maintained a list of all the books he read from January 1939 until he lost his sight in the late 1990s. Seven hundred books in total, ordered both alphabetically and chronologically, with a column indicating the month and year they were finished, and a column indicating how many books by that author had now been read. He kept this notebook by his bed, where he did most of his reading, for as long as I remember.

2 A slim Bible-black notebook inscribed on the inside flyleaf Engineering Formulae, Proofs, Definitions etc. Probably dating from the late 1940s/early 1950s. Three tiny handwritten tabs allow the reader to flip from AC to DC to M (for ‘mechanical’?); each page is numbered by hand, most are filled with neatly copied-out definitions (or proofs, or formulae) pertaining to his studies, in different shades of blue ink.

3 A book of recipes and food ideas, probably dating from his bachelor years in Bath. On the whole, an empty notebook. Avocado Pear and Prawns (no recipe, just the purity of a name). Rabbit pie. Roast meats. Something called ‘sausages – “burnt”’. Sophia Loren’s sauce for ‘spaghetti as used in Naples’. Some simple sweets (tinned grapefruit, tinned gooseberries, treacle pudding, lime jelly with grapefruit segments). All food he would still savour, if rarely actually cook, in later life (and if I recall he never lost his taste for sausages done to charcoal).

4 The flimsy green notebook in which he recorded the details of his tour of the Low Countries: train times, duty-free allowances, budgets, phrases in French (Je voudrais que vous fassiez chercher nos bagages); a list of what he had to declare at customs (perfume, earrings, chocolates and cheese, a pair of hair combs, a china jug, two hundred cigarettes, a bottle and a half of brandy); and a neat list of ‘places visited’ (Qualification: Towns and places in which we have set foot and toured, or taken refreshment, or both. Not towns and places passed through). Thus Ostend, Bruges, Blankenberge, Brussels, Vimy Ridge, Arras, Armentières, Ypres, Ghent, Antwerp, Luxembourg, Amsterdam.

5 His flying log, detailing each hour he flew (in Canada, in Northern Ireland, in Scotland, in Ceylon), with notes on weather, visibility, direction, radio contact maintained or lost, guns fired, etc., stamped here and there and signed by his commanding officers.

A skeleton of a life: My father’s notebooks.

And there it is. A skeleton of a life, in lists. Definitions. Formulae. Recipes. Etc. More than we have for Bruegel, by some considerable measure. For Bruegel, there is no such archival skeleton beyond those dates and signatures. We do not glimpse his book of recipes for rabbit-skin glue. His tour of the red-light district in Rome. We have only the vivid remnant flesh of the paintings and drawings and engravings.

For all the lack of documentation, we can say that the Bruegel Object, dispersed across hemispheres, nevertheless had an originating trajectory across a troubled land, a land in which images of all kinds were suspect, tortured, executed.

If you set up a boundary there will be a corresponding osmosis, a crossing, a new dynamic between zones. Breda is now on the Dutch side of the border, across from Antwerp, a Belgian town, but in the Spanish Netherlands, Breda was naturally a satellite of prosperous Antwerp a little to the south, not of pokey Dordrecht or Roosendaal, and still less of Amsterdam, hick town in the cold and peasant North. Antwerp was an intersection with the wide world; Holland was a puddle.

Over the next century, there would be a sorting, Catholic South to Protestant North, vice versa, as positions, professions of faith, hardened. Bruegel himself was likely a Catholic (he was given a Catholic burial), although in 1566 he would make a painting of a hedge-preacher going about his business (The Preaching of St John the Baptist in Budapest), and the humanist circles in Antwerp with which he had been associated moved freely and enquiringly in the space marked out by the old faith and the new, Erasmian accommodations and Calvinist defiance. Bruegel the artist was a product of secular print culture. He didn’t do altarpieces.

One year later, the project only just beginning to assume a shape, I visit Antwerp with my brother.

My brother’s departure is delayed at the last minute by a rescheduled job interview, so I travel out on my own, and while I wait for him I visit the Museum Mayer van den Bergh.

Like the Frick in New York, the Mayer van den Bergh is the ossified private collection of a wealthy industrialist. The floors creak, there are libraries and trinkets, furniture and paintings. On this weekday afternoon in February, I am alone with the guards, who follow me slowly from room to room. People cannot be trusted not to destroy images.

These are the things I recall. A large triptych by Quentin Matsys, with a crucifixion and a line of citizenry returning from Golgotha to the Holy City. A room not so much of sculpture as of bits of stone – medieval, Gothic, Roman, Etruscan. A large rustic painting by a contemporary of Bruegel’s, Pieter Aertsen. Aertsen was from the North Netherlands, based in Amsterdam, and painted peasant scenes and altarpieces; most of the altarpieces were destroyed in a later iconoclasm, the Alteratie or Changeover of 1578.

And there are a couple of Bruegels: Dulle Griet (1563) and Twaalf Spreuken or Twelve Proverbs (1558). Why else would I be here?

In 1562, Bruegel inaugurated his new primary focus on panel painting with a series, or sequence, or family of three panels of near-identical dimensions and congruent, Boschian subjects: Dulle Griet, The Fall of the Rebel Angels and The Triumph of Death.

Bruegel was known in his lifetime as the new Bosch. His works were marketed as such (and some of the earlier engravings – for example, Big Fish Eat Little Fish – were falsely signed Hieronymus Bos, probably at the instigation of Bruegel’s printer, Hieronymus Cock). To his contemporaries, he was not Peasant Bruegel, but Bosch-Bruegel. The earliest commentator on his work (Lodovico Guicciardini, writing in 1567) remarked on the rebirth in these latter days of the great visionary of the North (Bosch) in the person of Pieter Bruegel.

We now clearly see that Bruegel was a very different, and considerably greater, painter than Bosch. If Bruegel was an inheritor of the Bosch style early in his painterly career, he was also a humanist painter at ease with the carnivalesque, the Rabelaisian; Bosch, who died only a few years before Bruegel was born, was a medieval painter for whom monstrosity was an index of spiritual corruption. Bosch’s monsters mutate in Bruegel into something more arch, more playful; they are curiosities escaped from a Wunderkammer, not devils slithering up through the cracks in creation, less Satanic than Linnaean.

This is reflected in the catalogues of the two painters. Try drawing up a spreadsheet of All Bosch, a great Bosch Object, at your peril. You will never get beyond the tangle of Workshop of …, or School of …, or Follower of … The Bosch Object is all smoke and mirrors. The Bruegel Object is all meticulous documentation.

In Dulle Griet, a supersized and deranged woman is plundering in front of a hell’s mouth, marauding on the fringes of the human and spiritual worlds; she leads an army of tiny females who are engaged hand-to-hand with Boschian creatures and armed men. A second large figure, a giant, sits on top of a building with a ship of fools across his shoulders, ladling money out of his gaping arse. The panel is a melting pot of proverbs.

Baudelaire in the 1850s described Bruegel as a political artist. Perhaps this is the kind of thing he had in mind. The regent of the Netherlands was called Margaret, Margaret of Parma; Dulle Griet translates roughly as Mad Meg. The Netherlands are aflame and the devils are out, cities burning, society collapsing, imploding. But this is 1561 or 1562. While there are tensions, we are a few years out from the hedge-preaching and the Imagestorm, the Eighty Years’ War.

Perhaps it is a battle of the sexes, a reactionary taming of the (untameable) shrew, a world-turned-upside-down where women wield manic power, an uproarious crisis of authority. Or perhaps we should look at Bruegel’s drawings for the engravings of the seven deadly sins – there are parallels between Griet and the figure of Iracunda, or Wrath.

On the train on the way over I read an exhaustive and interesting essay by Margaret Sullivan in which she traces the iconography of the stock figures of Madness and Folly and links them to Meg and the giant respectively, but I find I can’t remember much about it as I stand here. I content myself instead with trying to work out the architectural division of the space, the logic of the towers and the curtain walls, and enjoying the ruddy sky.

‘Some pages [of Alexander Wied’s very good book on Bruegel] read like a parody of the frenzied activity of modern scholars – most strikingly the bewildering pages on Dulle Griet, who nonetheless remains triumphantly unexplained.’

Review by Helen Langdon of Alexander Wied’s Bruegel in the Burlington Magazine, January 1982

Do you formulate or access a reading or readings as you stand in front of a painting? Readings are always present – the art historian Michael Baxandall says that we do not discuss paintings but descriptions of paintings – but readings, or descriptions, are distinct from the process of observation. A reading, or a description, is grounded on a logical sorting, a winnowing of detail; observation is messier, more repetitive, obsessive, returning again and again to the same objects. Whatever readings or descriptions you arrive with, you can be sure the painting will cock a snook at them.

I suppose a professional might notice the way his or her attention drifts around the panel, recording shifts of attention as flickers of data. I am not a professional. I make, nonetheless, the following notes in my notebook: the experience of standing in front of Dulle Griet, I record, is one of dissipation. My attention fragments over the detail. I look closely, not broadly. It is an experience of noticing, in between bouts of inattention and mind-wandering: of looking with the eyes alone. It is not an experience of understanding. The things you thought you would see are not the things you see. Who knows what you now think? Who cares, really?

I do notice one thing above everything else. The sky is ruddier than I thought. I have never seen a sky remotely as ruddy as this in any reproduction. That sky really is burning. I stare at it. It is a colour field. You have a little psychological wobble if you stand in front of it long enough. Had Bruegel met Rothko or Van Gogh, they would have agreed on this at least: saturated colour impinges on you.

How? Emotionally? Viscerally? Not viscerally – whatever is happening is definitely happening in my head, somewhere behind my eyes. I feel, on this occasion, no emotion. Is it evocative? It does not evoke memory, or association. It is just an overriding perceptual stimulus. We have a less fully-worked-out network of descriptors for percepts than we do, say, for emotions, hence our difficulty discussing aesthetics. Percepts are just more or less noteworthy.

Yes, there it is: to stand in front of Dulle Griet is to experience a noteworthy percept, of ruddiness.

Perhaps painters in the sixteenth century – who had been apprenticed to other painters from a young age, grinding and mixing paints, staring at bowls and pastes and palettes of saturated colour morning to night, lost dreamy adolescents there in the workshop reeking of glues and sizes, while outside the world was passing through a duller, less superficial age, an age of few images and no industrial dyes – perhaps sixteenth-century painters, in short, were more sensitive to the allure of pure pigment.

The ruddy sky is all the ruddier for the silhouetted city, the rigging and towers and cavorting creatures picked out in front of it. The charred blackness brings out the red.

In particular there is a tower with a rigged flagpole: frogs, or frog-like entities, are climbing the rigging; a monkey watches from the tower. And one of the frogs is dancing a victory jig as the horizon burns. He is waving a spear. Elsewhere, more frog entities are dancing a round-dance on a tiered structure.

A burning city was not the most unusual sight in the sixteenth century: it was something to which the imagination, if not the eye, would have been accustomed.

In 1534, Bruegel’s putative hometown of Breda burned to the ground. Of 3,000 buildings, only 150 remained.

Such was the periodic fate of medieval cities, wooden towns. Like the forests renewed by wildfire, so too cities were regularly reduced by fire escaped from hearth or furnace or set (in the popular imagination) by conspiratorial arsonists communicating by means of secret signs placed on buildings. Come running with a bucket if you must, but this is how cities clear their undergrowth.

This ruddiness was the colour to fear in the sixteenth century.

‘The burning of forest began settlement,’ says Stephen J. Pyne in his history of European fire regimes, Vestal Fire: ‘the burning of cities ended it.’

On 14th May 1940, following a breakdown of communication (signal flares lost in the smoke of battle while the Dutch negotiated surrender), the Luftwaffe bombed Rotterdam. Some planes turned back, but a remnant fleet of fifty-seven low-flying Heinkel He 111s dropped 1,150 110lb and 158 550lb bombs on the Dutch forces holding the north bank of the Nieuwe Maas River. The wooden city burned for two days, the fires fuelled not only by the buildings but by tanks of vegetable oil located near the old port. An estimated 850 people died, and 85,000 were rendered homeless; 24,978 homes, 24 churches, 2,320 stores, 775 warehouses and 62 schools were destroyed.

On the day following the raid, British Bomber Command was instructed to alter its directives on so-called strategic bombing, and begin targeting cities of the Ruhr, including their civilian populations. The era of firestorms – Hamburg, Dresden, Tokyo – had begun.

Rotterdam would be bombed again, multiple times, over the next four years, by Allied forces. The city was no longer as combustible as it had been on 14th May 1940, but other forms of destruction were available.

*

‘When the invasion of Holland took place, I was recalled from leave and went on my first operation on 15th May 1940 against mainland Germany. Our target was Dortmund and on the way back we were routed via Rotterdam. The German Air Force had bombed Rotterdam the day before and it was still in flames. I realized then only too well that the phoney war was over and that this was for real. By that time the fire services had extinguished a number of fires, but they were still dotted around the whole city. This was the first time I’d ever seen devastation by fires on this scale. We went right over the southern outskirts of Rotterdam at about 6,000 or 7,000 feet, and you could actually smell the smoke from the fires burning on the ground. I was shocked seeing a city in flames like that. Devastation on a scale I had never experienced.’

Air Commodore Wilf Burnett, DSO

*

To make a painting is to hope that it will last. But none lasts for ever. Any singular object is a hostage to looting, theft, earthquake, fire, flood, bombing, and other local versions of the apocalypse. The post-war map of Europe, as of much of the globe, was excoriated, flattened, pounded to ashes; millions died and much was destroyed.

The Bruegel Object, so far as we know, was untouched. The paintings were smuggled underground, into mines and tunnels; when they re-emerged, they were unwrapped and dusted down and rehung, icons of resurrection. The yawning gaps in civilization crusted over, and on we went.

But it is only a matter of time and accident. When will the last Bruegel painting disappear? They are fragile. Which one will it be? And what about records of his paintings, his existence? Will his name vanish along with the last painting, or will he, some Apelles of a forgotten history, a forgotten Europe, persist as myth, the JPEGs flickering out on servers one by one, corrupt unreadable binary representations of long-forgotten cult objects?

One week before our Antwerp visit I get word that Anna Keen’s Amsterdam studio and home has burned to the ground. The shed next to hers, the one with the yachts or speedboats, caught fire around breakfast time; both it and Anna’s shed were flammable subsystems, wood and canvas and paper and gallons of volatile chemicals, boats and easels, sailcloth and packets of economy food. The whole lot went up in a plume of blue smoke so high it made the local TV news.

Anna got out in her pyjamas but lost everything else. Her studio was a workshop and a home for much of her life. In Rome, she would pick through skips for furniture, curiosities, would sketch endlessly with thick black soft charcoals and snub-nosed pencils and sometimes in pen and wash.

And now it was all gone. All her paints and painting equipment, unsold paintings and work in progress, rolls of canvas, stretchers, a lifetime’s sketchbooks, her library, her computer, her clothes, her documents, her electrostats (as she called them) and amplifier. Everything except her pyjamas, her bicycle and a small wooden dinghy she had bought in Venice. Nothing was insured. She had pressing debts, no income, and was several months pregnant with the child of a man who might or might not intend to stay around.

The next morning, she was out in the biblical wreckage of her life, sketching the twisted forms, picking over corners of vanished books, documenting the carnage. What else can you do? Habit will see you through.

I speak to Anna on the phone and suggest she come down to Antwerp, or meet us in Bruges or Brussels. Or we could come up to Amsterdam. But she has appointments to replace her passport and deal with legal problems of rent and deposits.

So I am in Antwerp, alone, waiting for my brother. Next to Dulle Griet hangs Twelve Proverbs, an early work, essentially twelve separate representations of proverbs in roundels, set within one frame on which the relevant proverbs (My endeavours are in vain; I piss at the moon – Ill-tempered and surly am I, I bang my head against the wall – I hide under a blue cloak, the more I conceal the more I reveal – He whose work is for nothing casts pearls before swine) are inscribed. There is a marbled decorative element and the backgrounds to the figures are a uniform red. The handwriting of the inscriptions dates the assembly to between 1560 and 1580.

It is, in fact, a set of apotheosized placemats. It was a popular format. Teljoorschilders, or plate-painters, were recognized as distinct craftsmen in the Antwerp painters’ guild between 1570 and 1610. Their plate-format paintings were usually set off against red backgrounds and had diameters of roughly 20 centimetres. They came in sets of six or twelve or twenty-four. Proverbs were an appropriate adornment, connected as they were with domestic wisdom.

A search for Bruegel proverb-placemats on Google throws up nothing. A missed opportunity, for someone.

What do you do in front of such an object (assuming you are not eating your dinner off it) if not read each proverb in turn, moving from the wall-plaque to the painting and back again?

Bruegel thought in proverbs. The proverb had pedigree as a rational device, formalized in Erasmus’s collection of adages, first published in 1500 and added to, revised, expanded for the next three decades. By the end of his life, Erasmus had collected 4,151 proverbs and adages and dicta, a list parodied by Rabelais’s parallel version in Gargantua of (mostly scatological) proverbs and mirrored by countless other collections through the sixteenth century.

We like to think we have left proverbs behind. We demonstrate our intelligence by sharply differentiating ourselves, picking out the anomalous, the noteworthy, the untoward in the world around us; we hunt out the discrepancy on the untidy fringes of knowledge because it is here that we will locate the telling detail, pull at the loose thread, which will in turn explode the commonplace that threatens to engulf us. ‘Insignificance is the locus of true significance,’ said Roland Barthes; ‘this should never be forgotten.’