Читать книгу Death Falls - Todd Ritter - Страница 6

JULY 20, 1969

ОглавлениеIt was the baby, of all things, that woke her up. Not her husband. Not the police. Just the baby and his crying.

Maggie had grown accustomed to the sound. Having two kids did that to you. Sometimes she’d accidentally sleep right through whatever racket one of them was making. But that night was different. The crying was different. It wasn’t the irritated wail of an infant who was tired or the pained whimper of one who was teething. It was, Maggie realized, a cry of terror, and the noise tugged her out of sleep, out of bed, and out of the room.

Along the way, her bleary eyes caught the clock on her dresser. It was almost eleven. She had been asleep for more than three hours. Not as bad as some days, but not good, either. Not good at all. And despite the rest, she still felt weary as she crossed the hall to the nursery. Still utterly exhausted.

In the nursery, Maggie flicked on the overhead light. The sharp, sudden glow made her eyes sting in addition to being bleary. It didn’t matter. She could navigate the room with her eyes closed, which is exactly what she did. The memories of hundreds of similar trips guided her—rocking chair to the right, dresser to the left, don’t stub your toe on the toy chest. Once she reached the crib, Maggie opened her eyes.

The crib was empty.

The crying, however, continued.

Maggie heard it, loud and fearful. She rotated in the center of the room, looking for a possible explanation. Had the baby somehow escaped the crib and crawled into the closet? The dresser? Another room?

It was only after two more twirls that Maggie’s sleep-addled mind caught up with her spinning body. When it did, she realized the source of the crying wasn’t in the nursery at all. It was coming from downstairs and had been the entire time. Only now it sounded more urgent, more frightened.

Maggie left the nursery and clomped down the stairs. At the bottom, she expected to see Ken reclining in the living-room La-Z-Boy, the baby wriggling in his arms. Instead, the chair was occupied by Ruth Clark, whose spindly arms struggled to stay wrapped around the writhing child.

Ruth, who was only sixty but looked at least a decade older, lived down the street. She and Maggie were friends, but not friendly enough for Ruth to be in her house, holding her child, at almost eleven o’clock at night. Yet there she was, trying to hush the baby in the gray glow of the television.

“Ruth? What’s going on?” Blinking in confusion, Maggie noted what her neighbor was wearing—a nightgown stuffed into threadbare trousers, flip-flops on her feet. She had dressed in a hurry. “Where’s Ken?”

“You were asleep,” Ruth said with forced cheer. “So he asked me to come over and keep an eye on the baby. He had to step out for a minute.”

“Why?”

Ruth stayed silent as she pressed the baby into Maggie’s arms. He had been wrapped tightly in a blanket, which covered everything but his face. Whether it was Ken’s doing or Ruth’s, Maggie didn’t know. Either way, it was a bad move on such a muggy night. Both the baby and the blanket were drenched with cold sweat, which explained the bawling.

The crying softened once Maggie settled onto the couch and loosened the blanket. Ruth sat next to her, uncomfortably close. She was hovering, Maggie realized. And watchful.

“Did Ken say where he was going?”

Ruth’s reply—“He didn’t”—was rushed and unconvincing.

“What about when he’d be back?”

“Soon.”

“I’ll wait up for him. You don’t need to stick around.”

“I think I should stay.”

Maggie didn’t have the energy to protest, not that Ruth would have allowed it. The finality of her tone made it clear she intended to stay. With nothing left to say or do, Maggie stared at the television.

What she saw astounded her.

The screen was mostly a grainy blur—fizzy patches of black and gray. Then an image took shape through the haze. It was a figure in a bulky uniform, looking like a ghost against a background of endless darkness. The figure was on a ladder, hopping downward rung by rung.

It paused at the bottom. It placed a foot onto the ground. It spoke.

“That’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.”

“Sweet Lord,” Ruth said. “He’s really standing on it.”

He was Neil Armstrong. It was the moon. And Ruth was correct—the astronaut was standing on its surface just as easily as Maggie now sat in her living room.

Eyes fixed on the TV, she immediately thought of Charlie. Nine years older than the baby, he had been moon crazy the past year. Earlier that afternoon, when Apollo 11 actually touched down on the moon’s surface, Charlie had cheered, jumped, and cried until he made himself sick.

He would want to see this, Maggie knew. History was taking place.

“I’m going to wake Charlie.”

Ruth trailed her to the stairs. “Maggie, wait!”

Maggie didn’t stop, continuing up the stairs with rushed purpose. At the top, her bare feet made slapping sounds on the hardwood floor as she moved down the hall to Charlie’s bedroom. Ruth remained downstairs, calling up to her.

“Please come back! Charlie’s not there!”

Maggie stopped, hand against the closed bedroom door. “What do you mean?”

“Come back downstairs,” Ruth said. “I’ll explain.”

Maggie did the opposite, pushing into the room instead. The streetlight outside the window cast a rectangle of light that stretched across the floor. Just like in the nursery, she didn’t need it. She knew every inch of the bedroom, from the telescope in the corner to the model rockets lined up on the bookshelf.

The window was open, letting in a rainy breeze that dampened the curtains. Beneath it was Charlie’s bed, draped in a comforter dotted with moons, stars, and planets. Holding the baby with one arm, Maggie used her free hand to lift the comforter and whip it away.

The bed, much like the baby’s crib earlier, was empty.

“Please come downstairs.” Ruth now stood in the doorway, breath heavy, face pinched.

“Where is he? Did Ken take him somewhere?”

Ruth moved into the room and tried to clasp her hand. Maggie yanked it away. “Answer me, Ruth. Where is my son?”

“He’s missing.”

“I don’t understand.”

But Maggie did. She understood quite well as she shuffled backward and plopped onto the empty bed. The bed that should have contained Charlie. Her boy. Whose whereabouts were now unknown.

“Is that where Ken went? To look for him?”

“He called the police,” Ruth said. “Then he woke me and Mort.”

Mort was Ruth’s husband. Maggie presumed he was also looking for Charlie, along with the police and God knows who else. Apparently everyone but her knew her son was gone.

“Why didn’t you tell me?”

“Ken didn’t think you’d wake up. And if you did, he knew you’d be worried.”

Damn right she was worried. Her body might have been motionless on her son’s bed, but her mind was a whirling dervish of fears and bad thoughts. Where was Charlie? How long had he been gone? Was it too late to find him? When Maggie’s brain settled down, her body started up again. She rose from the bed and stomped past Ruth into the hallway.

“I have to look for him,” she said. “I have to find him.”

Again, Ruth tried to stop her. “I’ll take the baby.”

“No.”

Maggie tightened her arms around the infant. One of her children was missing. She wasn’t going to let the other out of her sight until he was found.

She descended the stairs into the living room. The TV was still on, still broadcasting surreal pictures from another world. A second astronaut had joined Armstrong, both of them leaping like jackrabbits across the moon’s surface. Maggie moved right past it, not caring. Her only concern was her children, not the moon, or the astronauts, or the fact that she was running outside in the rain in bare feet, denim cutoffs, and a T-shirt stained with baby puke.

She made it to the end of the driveway before seeing two men approach the house. One of them was Ken. The other was Mort Clark. Maggie looked past them, hoping to see Charlie lagging behind. He wasn’t.

“Did you find him?” Maggie asked as she met them in the middle of the street. “Where is he?”

“I don’t know,” Ken said. “I have no idea.”

He looked pale and haunted—more ghostlike than those astronauts on TV. The rain had flattened his hair. Large drops of it clung to his beard.

“We were watching TV,” he said. “They were showing stuff about the moon landing and Charlie said he wanted to go for a bike ride and look at it. He said he thought he’d be able to see the astronauts from here.”

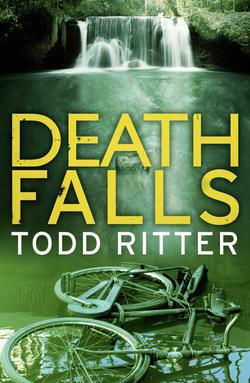

It was a ridiculous notion, but very much in line with Charlie’s thinking. Maggie easily pictured him hopping on his bike—midnight blue with badly painted stars—and pedaling off in excitement.

“How long ago was that?”

“About an hour.”

“Where did he go?”

“The falls.”

One of Charlie’s favorite places was the creek that rushed through the woods behind their cul-de-sac. There was a dirt path there, perfect for biking, that led to a footbridge. From that perch, you could see the water hurtle over Sunset Falls, which plunged thirty feet into a rock-strewn pool. They had allowed Charlie to ride there alone for the first time this summer. Maggie now regretted that decision.

“Did you check the bridge?” she asked.

When Ken sighed, Maggie suddenly felt the urge to hit her husband. She would have done it, too, had she not been holding the baby. She would have let loose with a few good punches while asking Ken why he didn’t go with their son, why he couldn’t find him, why he was talking to her instead of still looking for Charlie.

“Of course I checked the bridge. It was the first place we went. The police are still there.”

Then they needed to look somewhere else. She needed to look somewhere else, since Ken had made it clear his searching was over for the night. Maggie felt herself moving away from him, compelled to do something. Charlie wouldn’t be found with her just standing there.

“Where are you going?” Ken asked.

Maggie didn’t answer. Wasn’t her destination perfectly clear? She was going to find her son. End of story.

Ken called after her, his voice muted in the rain. “I think you should leave the baby with me. I don’t—”

He stopped himself, but it didn’t matter. He might as well have just finished the sentence and let the truth escape. He didn’t trust her with the baby. Not after what happened in May. It’s why he hadn’t bothered to wake her when Charlie went missing. It’s why he had sent Ruth to watch the baby earlier. It’s why he was trying to stop her from leaving now.

But Maggie couldn’t stop. Her body wouldn’t let her. She had no choice but to cross the street, even as the rain increased in force. Even as Ken begged her to come back. And even as the distance between her and her husband grew wider with each passing step.

There were four houses on the cul-de-sac, set apart by wide lawns and rows of sycamore trees. Ken and Maggie’s was by far the smallest—practically a cottage—and the most full. Two parents and two kids, crammed together in a house that Maggie struggled to keep clean. Across the street, in a cruel reflection of her own abode, sat the home of Lee and Becky Santangelo. It was everything Maggie’s house was not—large, rambling, spotless.

With Ken watching her from the driveway, Maggie crossed the Santangelos’ yard. It was so much larger than her own, an expanse of crisp green kept trim by a local teenage boy. At the moment, though, it was soggy with rainwater. It squished between her toes as she made her way to the front porch. Once there, she grabbed the giant brass knocker that dominated the door and rapped twice. When no one answered, she knocked again, this time slamming continuously until Lee Santangelo eventually opened it.

Like their disparate houses, Lee was the complete opposite of Ken. He was taller, for one thing, and far more handsome. Strong build, matinee-idol looks, always clean shaven. Normally, he was pleased when Maggie dropped by with Charlie and threw the door wide open for them. But this night was different. The door opened only a crack as Lee peered at her with a mixture of surprise and annoyance.

“Maggie,” he said, pretending to be happy to see her. “What’s going on?”

They were the same three words Maggie had used to greet Ruth Clark. Hearing them directed at her, she realized just how rude and suspicious they sounded.

“It’s Charlie. We can’t find him.”

Music was playing loudly inside. Something psychedelic that Maggie couldn’t place. Beyond that, barely audible, was a constant whirring sound. When Maggie tried to peek inside, Lee blocked her view with a quick side step. Seeing the length of his body, she realized he was wearing next to nothing—a pair of boxer shorts and an unbuttoned shirt, tossed on no doubt for her benefit. It didn’t matter. He could have been stark naked and she wouldn’t have cared.

“And you think he could have come here?” Lee asked.

“With all this moon business going on, I thought he might have stopped by. You know, because—”

Because Lee Santangelo was an astronaut. Or had trained to be one. Or had almost been one. Maggie didn’t know the details. She only knew that Charlie had driven him crazy with questions all summer.

“He hasn’t been by tonight. I’m sorry. But I’ll definitely keep an eye out.”

“If you see him, please tell him we’re looking for him. And that we’re worried.”

She added that last part in the hope that Lee would fling open the door and let her look around the place. Instead, he tried to close it. Maggie, thinking fast, blocked the door with her foot. The squeeze of it against her big toe made her wince.

She persisted, despite the pain. “What about Becky?”

“What about her?”

“Maybe she saw him tonight.”

Maggie knew Charlie had a crush on Lee’s wife, even if the boy didn’t know it himself. It was well within reason that Charlie could have bypassed Lee and instead sought out Becky, who offered him cookies, tousled his hair, and tut-tutted over his scraped knees.

“She’s not here,” Lee said slowly. “She’s gone until tomorrow. I’m the only one here.”

And that, Maggie realized, was all the information she would get at the moment. Time was ticking, and every second spent with Lee Santangelo was another second wasted in the search for her son. So she thanked him for his time, apologized for bothering him, and moved on.

She was halfway across the lawn when a sudden movement from the Santangelos’ house caught her eye. It was a curtain being rustled in a second-story window. Maggie saw a shadowy face peek out from behind it and stare down at her. She kept walking, pretending she hadn’t noticed. But when she reached the edge of the yard, she allowed herself one last, quick glance. What she saw was a silhouette standing in front of the window. Maggie could make out a thin frame and shaggy, shoulder-length hair.

A woman.

Maggie didn’t have a clear enough view to see if it was Becky Santangelo. But who it was didn’t really concern her. What mattered was that Lee had lied. He was definitely not alone.

Pebbles jutted into the soles of Maggie’s bare feet as she crossed the street. Each stone she stepped on caused a small flare of pain. For that, she was grateful. It took her mind off the knot of worry lodged in her chest. The distraction was only momentary, but considering the circumstances, she’d take what she could get.

In front of her house again, Maggie noticed that Ken had finally gone inside. Through the front picture window, she saw him pacing in the living room. His mood earlier had been maddeningly unreadable—equal parts annoyance, worry, and prickliness. But the unfiltered view through the picture window showed a man who was clearly distressed. He stared at the floor. He tugged at his beard. He closed his eyes and pressed a thumb and forefinger against the bridge of his nose, which Maggie knew meant he was trying to stave off a headache.

Part of her wanted to return to the house and comfort him. Despite all the mistrust of the past few months, she still loved him deeply. But Maggie needed comfort, too. She knew that would only come once Charlie was found safe and sound. So she pressed on, even though her arms were tired from carrying the baby and her legs were weak with worry.

She was also running out of neighbors. Besides the Clarks and the Santangelos, there was only one other house on the street, and it was the last place she expected to find Charlie. Still, she at least had to ask, even though she dreaded doing it.

Her destination was the house next door to her own. The oldest on the street, it was an exhaustingly ornate Victorian that looked ancient compared with her own home. Charlie liked to pretend it was haunted. He claimed children were buried in the backyard and that their ghosts roamed the house at night. Maggie had no clue what gave him such ideas, but she understood how the house’s appearance played a part in fueling his imagination. Black shutters flanked the tall windows. A widow’s walk on the roof seemed to lean in whatever direction the wind was blowing. The wraparound porch had an unused swing and brittle steps that threatened to break when Maggie climbed them.

Although the house was dark, she knew its owner was home. He was always home.

“Mr. Stewart?” Maggie shifted the baby’s weight to her left shoulder and knocked on the door with her right hand.

No one answered, which didn’t surprise her in the least. Glenn Stewart never answered his door. Nor, as far as Maggie could tell, did he go outside.

“Mr. Stewart? Are you there?”

Maggie knocked again, remembering the last time she had seen him, during that awkward homecoming party. The whole debacle had been her idea. Glenn had no family that she knew of, and she felt sorry he was returning from Vietnam to an empty house inherited from his grandparents. So she baked a cake, rounded up the neighbors, and marched next door, intent on creating a happy homecoming through sheer force of will.

Glenn had wanted nothing to do with it. He wasn’t rude when he opened the door and saw seven people (seven and a half, if you counted Maggie’s very pregnant stomach) applauding on his porch. He looked more scared than anything else, twitching like a rabbit facing a pack of wolves. But he refused to let them inside and declined the cake, which Maggie thrust at him desperately. Not knowing what else to do, she had left the cake on the porch, hoping Glenn would retrieve it later. Then they left, taking the hint. Glenn Stewart wanted to be left alone.

But now Maggie couldn’t leave him alone. Not until she knew if he had seen Charlie. So her knocking turned to pounding.

“Mr. Stewart? It’s Maggie Olmstead from next door.”

Dropping her head in frustration, Maggie noticed something sitting on the porch floor, about a yard away from her feet. It was the cake—ravaged by birds, bugs, and four long seasons—sitting exactly where she had left it a year earlier.

Retreating from Glenn Stewart’s house, Maggie saw two police cars at the end of the cul-de-sac, where the asphalt ended and the footpath into the woods began. Twin beams of light swooped through the trees. Flashlights, scanning the darkness for her son.

One of the lights suddenly stopped. A voice rose from the woods.

“I think I see something!”

The second light bobbed swiftly toward the still one. Maggie moved, too, running toward the forest. She no longer felt the pebbles under her feet or the rain stinging her face. The only things she felt were the baby wriggling in her arms and the knot of worry expanding to all points of her body.

Her other senses, however, were heightened to an alarming degree. When she reached the path and pushed into the woods, her eyesight never dimmed. The smell of wet earth, moss, and maple sap clogged her nostrils. Her ears practically buzzed at the sound of boots tromping through the underbrush and voices murmuring to each other.

Then there was the creek. She saw the water’s glint, smelled its banks, heard the discordant rush as it approached Sunset Falls and plummeted over.

Two men were standing at the footbridge when Maggie reached it. One of them was Deputy Owen Peale, his face obscured by a hooded poncho. The other was the police chief, Jim Campbell. He eschewed the poncho in favor of a wide-brimmed hat. Maggie’s presence startled both of them.

“You shouldn’t be here, Maggie,” Jim said.

“Did you find Charlie?”

He tried to turn her around, away from the water. “What are you doing out here with the baby? You’re sopping wet.”

Maggie refused to budge. She craned her neck until she could see over the chief’s shoulder. Behind him, Deputy Peale had his flashlight pointed toward the stream.

“Is Charlie there?” she asked. “Is he okay?”

“Let’s get you home,” Chief Campbell said, his voice telling Maggie everything she needed to know. It was falsely optimistic, bordering on condescension. Something was wrong.

The baby began to stir in Maggie’s arms, more forcefully than before. A cry erupted from the infant, as loud and fraught with terror as the one that had awakened Maggie in the first place.

“How about you give me the baby,” Jim said. “I’m drier.”

When he held out his arms, Maggie made her move. She swerved past him and sprinted up the path. Deputy Peale lunged for her at the bridge, but she scooted right, just out of his reach. Then she was on the bridge, bounding across it until she was directly over the water. In the distance, about twenty yards away, the creek ended and the falls began.

Looking down at the water, she saw a branch emerge from under the bridge, riding the rain-swollen creek. It floated along the surface before hitting a rock and briefly stopping there. But the persistent current didn’t allow it to stay in place for long. Water swirled around the branch like tentacles until it was dislodged. The branch was whisked onward to the edge of the falls, where it slid from view.

Over, down, gone.

Maggie heard Jim Campbell yelling her name. She saw Owen Peale now on the bridge, approaching slowly and saying “It’s okay, Mrs. Olmstead. It’ll be okay.”

Her eyes turned back to the falls, where the branch had just tumbled into darkness. She traced its path, gaze swimming against the current. Soon she was looking off the other side of the bridge, her back to the falls. The creek there looked just as wild. Leaves, sticks, and globs of trash floated toward her and slipped beneath the bridge. There were rocks there, too, large boulders that poked out of the water like icebergs.

Owen Peale had reached her by that point. He clutched her shoulders and shook his head. “Don’t look. Please don’t look.”

That was when Maggie saw what she wasn’t supposed to see. It was an object caught on the rock closest to the bridge, pinned there by the current. It was blue. A blue so dark she could barely make it out. There were spots of white, too, ragged blotches that vaguely resembled stars.

Maggie screamed.

It was Charlie’s bike. Right there in the water. The current caught the spokes of the front tire and rocked it back and forth.

Jim Campbell joined them on the bridge. One of the men, Maggie didn’t know which, took the baby. The other tried to pull her away from the bridge railing. Maggie allowed herself to be moved. She didn’t have the strength to fight it. She simply went limp as she was dragged off the bridge. Along the way, she took one last glance toward the creek, even though she knew she shouldn’t. She had to see it again. Just to make sure it was real.

She saw the water dislodge the bike, just as it had moved the branch earlier. Caught on the current, the bike was submerged for a moment. It poked out of the water again on the other side of the bridge, riding inexorably toward the falls. When it reached the edge, the bike overturned, rear tire spinning. Then it slipped away, riding the falls.

Over.

Down.

Gone.