Читать книгу Why Ghosts Appear - Todd Shimoda - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеWalking past the noodle stand, I heard a bang of pots and smelled the salty, meaty simmering broth. The stools lined up at the bar were clean but cracked and worn to a point that the white foam padding was exposed along the seams. A man and woman, probably the owners, were getting the stand ready to open. In another five or six steps I came to the gravestone carver. A layer of fine, glittering dust coated the alley. From inside the workshop came the whirring of a rock polisher. Past the carver’s shop, I came to the three shrine cleaners who gave me another formal bow. This time I was able to execute one of my own. Whatever I did made them titter. With my briefcase and suit-and-tie apparel, I must have looked like a salesman. Perhaps they had a private joke about salesmen.

Viewed from this plane, that is, walking rather than driving, the neighborhood developed only a little more significance. The mechanic revealed himself as an apprentice given responsibility before his time and experience should have allowed. The noodle stand owners were no doubt barely surviving financially. The gravestone carver would likely develop silicosis from inhaling dust particles. These stories of the residents added confirmation to the claim that the neighborhood lacked significance.

But then such significance can only be contextual, a relative comparison. For example, comparing Neighborhood A to Neighborhood B with facts and figures such as population density and socioeconomic status gives us measures that can be analyzed side-by-side. If, however, we are able to observe the internal significance of the neighborhood to the people who live there we can find a different measure, a more subjective degree of significance. Now we have entered the realm of human motivation and desires. The ability to make such observations should be part of being a skilled investigator. Unfortunately, I am not so skilled, and I’m entirely satisfied to make enough to pay my rent and eat.

The path leading up the hill was exactly where the retired nun—I decided to anoint her with that title—said it would be. The path’s stones were placed too close for my stride and my steps were mincing. At the top of the hill, really not much more than a rise, were three houses. The one on the left bore the address of the woman whose son was missing. A string of red lanterns signifying the beginning of the ancestor’s festival was hung from the door to a pole stuck in the ground a short distance away from the home. The lanterns invited and guided spirits to the home; however, as the festival was now over, they should have been taken down. This indicated a certain state of mind—most likely the woman’s concern for her missing son.

The front door was open so I stepped inside the cool entryway. Shoes and slippers were placed haphazardly on the stone floor. A large lantern decorated with the image of a hand, palm-side out, leaned against the opposite wall. “Hello?” I said.

After a moment there was a rustling, like someone putting papers in a box. A woman of some fifty years of age appeared and bowed deeply while apologizing for not meeting me at the door of her messy home—her description not mine. Her hair was white, shockingly so since she was not that much older than me. It was styled to frame her face elegantly, giving her an aura of great intelligence and knowing. That image would be good for her line of work.

“There’s no need to apologize,” I said. “I didn’t realize I had arrived so early.” I presented her one of my business cards.

She studied it for precisely three seconds before she said, “No, you’re not early. Come in.” She selected a pair of house slippers for me to wear. I slipped out of my shoes and wriggled my feet into the slippers at least one size too small. When I looked up, she was studying me, no doubt sizing me up as she would a new client, searching for clues as to personality, profession, and troubles which she could exploit in her vocation.

The fortuneteller hurried ahead into the house. I followed with less speed and passed by the door to a side room containing a table and two chairs. Two lamps cast a dull yellowish glow through their paper shades. Most likely, the room was where she told her clients’ fortunes. The room exuded a coldness. I turned away.

The woman stopped in the main room of the small, dimly-lit house. She whacked a couple of cushions and set them on the floor in front of a low table. After gesturing for me to sit, which I did after putting my briefcase on the table, she scurried into the kitchen before I could tell her I didn’t need a refreshment.

A traditional altar for the ancestor’s festival was set up in the room. Next to the altar was a cucumber decorated to resemble a horse (giving the spirits a quick ride home) and an eggplant like a cow (to keep the spirits around once they arrived). Both decorated vegetables were splotched with mold. Clearly, her son’s failure to visit disrupted her celebration of this year’s festival.

A wave of depression flowed through me. The worn-out neighborhood, the residents going about their lives in slow motion, and the fortuneteller’s dark home with disintegrating decorations, created the negative energy. It was as if the locality were a black hole from which no signs of life could escape. I reached instinctively for my cigarettes but there were none. I was trying to quit.

I was about to get up to examine the framed pictures on the wall—one was of a man likely to be her missing son as there was a noticeable resemblance—when she returned with a pot of tea and two cups. While she served us, she apologized for living in a place so difficult to find. I said it was not so difficult, although I didn’t mention the nun’s help.

“Good,” she said.

I took a sip of tea and made an appropriate sound of satisfaction, though in fact the tea was too weak for my taste. “Your line of work is interesting,” I said, opening with small talk.

“Not too interesting,” she demurred. “People hear what they want to hear.”

I was surprised by her honesty. The fortunetellers I previously encountered, as few as they were, espoused the occupational line that they possessed mystical gifts allowing them to peer into people’s souls and predict their future.

I asked, “Is business good during this time of economic prosperity or do you find people needing your services less because of it?”

“Business is better than ever,” she said. “People are consumed by the future. They believe they can become wealthy if they only know which direction to take, or which family to marry into. No one, almost no one, cares about love or happiness.”

As she spoke, her gaze darted in seemingly random patterns. Following the path to determine what she might be looking at was impossible. But she was obviously taking in something. I glanced around the room. The walls were spotted with shadows and the longer I stared at a spot the darker and larger it became, increasing my dread of falling into a black hole. The more I stared, the more I was pulled toward the darkness. Well, actually, it was like half of me was being pulled; the other half remained securely in place on the cushion. My being was stretching and cleaving apart. Oddly, the phenomenon also generated a calm certitude, as if my own death were coming in a matter of hours and I had fully accepted it.

I looked away and gulped a swallow of tea. Clearing my throat, I opened my briefcase and took out the fortuneteller’s application for services, a notebook, and a pen. “How old is your son?”

“Twenty-nine,” she said.

To assure her of my professionalism, I made elaborate motions of writing down her answer. “When was the last time you saw or talked with him?

“Last year’s ancestor festival.”

She answered with a clipped response, implying that it should have been obvious. Of course, she had already given this information to my supervisor. “Mrs. Mizuno, I apologize if you’ve already answered these questions but I find it necessary to verify information obtained by others. Call it my style.”

The fortuneteller’s expression didn’t change as she focused her gaze fully on me. After a moment a tiny smirk arose at the corners of her mouth and she gave me a little nod. The actions might be patronizing but I couldn’t say for sure.

“Where does your son live?” I asked as if nothing had happened.

She recited his ward, block, and apartment number.

“Thank you. What have you done to find him?”

She blinked a couple of times. “Call your company.”

“You didn’t try to contact him?”

“Of course I tried. But I got nowhere.”

“How about the police?”

Her head twitched as if she suddenly remembered something vital. “No police. Besides, they wouldn’t give me the time of day.”

She was right about the lack of police interest in such a case—it was too soon, too common, for a son nearly thirty years of age to be out of contact with his mother. And she probably didn’t want authorities poking around her professional life. Fortunetellers operate on the fringe of legality. Instead I asked, “Who are his closest acquaintances?”

“None whom I know. He’s a bit of a loner. He had a few friends in school but they all drifted away. He hasn’t mentioned anyone lately.” She paused, then added, “Male or female.”

“How about enemies?”

“Heavens no. What are you thinking?”

The trouble was, I wasn’t thinking. Rather, my questions were routine. The case unfolding before me was premature, lacking substance. Only a few days had passed from when the son should have visited. Nothing yet indicated there was an alarming situation.

“Please forgive me,” I said. “I meant nothing. Again, it’s simply a matter of routine. How about his work? I understand he is a freelance illustrator of insects.”

She got up and pulled a book off a nearby shelf. “The book came in the mail more than two years ago.”

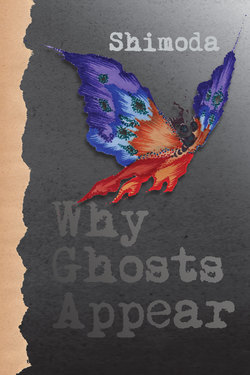

It was a book about butterflies and moths, the text in English and Japanese. There were photographs and intricate hand-drawn illustrations. “I assume your son drew these?” I asked her, pointing to one of the illustrations.

“Yes.”

“He does beautiful work. May I borrow the book and a picture of your son? I will be sure to get them back to you without damage.”

“Of course you will,” she said matter-of-factly.

Her statement gave me a start, as if she knew my future.