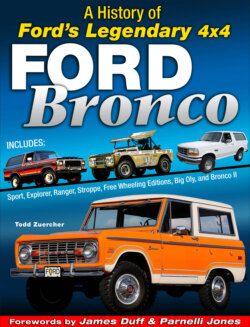

Читать книгу Ford Bronco: A History of Ford's Legendary 4x4 - Todd Zuercher - Страница 27

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Body

ОглавлениеThe Bronco featured body-on-frame construction, combining a ladder frame with a unitized body (the cargo section of the body and the front seat and engine area were all one piece rather than separate structures as on conventional pickup trucks). The Bronco’s frame was fully boxed along the length of its two rails and its two primary crossmembers, which made it extremely strong and stiff. The combination of the Bronco’s unitized body and strong frame made it about three to four times torsionally stiffer than a pickup truck of the same era. Adding a roof increased the torsion and bending stiffness and adding doors increased the bending stiffness. The front and rear bumpers also provided a substantial contribution to the torsional stiffness.

This test involved test dummies in the front and rear seats, with dummy number-9 eerily looking at the camera as the front of the truck collapses around its legs. The rear-seat dummy has an arm outstretched, likely mimicking the reaction of a passenger in such a collision. (Photo Courtesy Jeff Trapp)

This Bronco intentionally being destroyed is a cringe-worthy moment for enthusiasts today. An instrumented “crash test dummy” is leaning forward in the rear seat. The front buckets are leaning forward and based on the location of the body relative to the axles, it appears the body has shifted forward on the frame. (Photo Courtesy Jeff Trapp)

Caught in mid-roll by the camera, window glass flys across the grass ahead of the rolling truck. A complete drivetrain is visible on this test vehicle, suggesting that a complete vehicle was used for the test. Based on the trees in the background and the terrain, all of these test photos appear to have been taken at the Dearborn Proving Grounds. (Photo Courtesy Jeff Trapp)

SUSPENSION DEVELOPMENT

The development of the monobeam front suspension is a fascinating story. The initial design of the suspension was done in parallel with the development of the famed Twin I-Beam 2WD front suspension, which was introduced on 1965 Ford pickups. In the early 1960s, a feasibility vehicle was built to design and test the monobeam front suspension. Based on a 4WD pickup, it featured a 5-foot cargo bed and rode on a 106-inch wheelbase.

The truck was built in several configurations with both 6- and 8-cylinder engines and 3- and 4-speed transmissions in front of a single-speed transfer case. The evaluation of this vehicle confirmed the desired handling, maneuverability, and performance of the monobeam front axle concept.

The feasibility vehicle’s radius arms for the suspension were stamped pieces taken from a Twin I-Beam suspension and modified at the ends to attach to the monobeam axle housing. These radius arms attached to the axle housing with large rubber bushings, which worked fine in testing but were deemed to be unnecessarily complex for production. The final design used forged radius arms that clamped wedges on the axle housing with rubber isolators between the arms and the axles. Ford tested this configuration for 500,000 cycles without failure and deemed it acceptable for production.

A vehicle that uses a leading arm suspension like the monobeam front end with radius arms requires some type of lateral control for the axle as well. Ford chose to use a panhard rod, or track bar in Ford lingo, to locate the front axle. Because the location of the track bar is critical from a vehicle handling standpoint, Ford tested several mounting locations for the bar mounting points and tested them on ride and handling courses to arrive at the ideal configuration. After the mounting points were set, a complete track bar system was fatigue-tested in the laboratory by subjecting it to simulated vehicle loads for more than 1,000,000 cycles without failure.

It’s a little-known fact that the first Bronco package study included mirror-image front and rear suspensions. A similar configuration was later used by other manufacturers, but in the early 1960s, Ford decided against coil springs in the rear due to the encroachment into that ever-important ramp break-over area by the radius arms and their mounting brackets.

Instead, Ford used a traditional Hotchkis-type suspension with leaf springs anchoring each rear corner. With the standard 3,900-pound gross vehicle weight (GVW) package, the leaf springs had five leafs and the optional 4,700 GVW package springs had six in their packs. Rear shocks were mounted angling forward from the axle to the frame with stud mounts on top from the Bronco’s introduction until March 1966, when Ford switched them to angling rearward with eye mounts on top. The location and mounting configuration remained that way through the end of the first generation’s production in 1977.

Due to the Bronco’s weight and short wheelbase, the Bronco was never known as a great tow vehicle. Ford did offer a trailer hitch for the Bronco as a dealer accessory and rated the tow capacity at 2,000 pounds.

This cross-sectional view shows the attachment of the radius arm to the front axle on the feasibility vehicle (modified 4WD pickup truck) compared to the design used on production Broncos from 1966 to 1979. (Photo Courtesy SAE International)

Exceeding its rated towing capacity, this 1966 Bronco pulls the most valuable payload ever pulled by a Bronco: the 1966 Le Mans–winning GT40 of Chris Amon and Bruce McLaren. The GT40 sold for $22 million in 2016. (Photo Courtesy John Fowler)

The earliest Broncos had a host of water leakage problems, so Ford issued a series of Technical Service Bulletins with recommended fixes. They usually involved applying copious amounts of silicone sealer and, in one case, drilling 15 holes in the floor under the floor mat so the water could drain. Imagine such a fix being recommended today.

The Budd Company conducted testing on a bare frame and a body-on-frame before the first mechanical prototype was built. After gathering input from the monobeam-equipped feasibility vehicle and another truck run on some durability courses, Budd subjected the frame to 70,000 pothole cycles at each wheel and 308 lateral loads for each 1,000 pothole cycles.

Based on the results of this testing, Ford modified the design of the transmission/transfer case crossmember and added K-braces to the front and rear crossmembers, which after additional testing, proved to be successful and were incorporated into the production frame design.

The first frame design also had all the body mount brackets and suspension hangers welded to the frame rails. After some additional fatigue analysis, several of these members were instead bolted or riveted to the frame and the radius arm brackets were both bolted and welded to the frame. Further body testing brought about some changes, including relocation of cross sills, tunnel and front floor surface changes, mounting flange revisions, and additional material to strengthen panels.

The pieces in the corners of the frame rails and the front crossmember on the Bronco frame are called K-braces. Budd Company’s initial testing of prototype Bronco frames showed that they did not meet requirements for torsional rigidity, so these braces were added. (Photo Courtesy Tim Hulick)

These metal tags are known as buck tags. They were wired to the firewalls of 1966 and 1967 Broncos and indicated to assembly-line workers what was supposed to be on the Bronco. The black tag is from an early truck and spells out what should be installed. By the time of the teal tag, the words were shortened to abbreviations. Trying to decipher these tags can be a challenge. (Photo Courtesy Tim Hulick)

The body was mounted to the frame with eight rubber mounts, offering excellent frame-to-body isolation. In addition, the mounts were designed for ease of assembly. All of the mounts were installed on the frame line and when the body was installed, an assembly-line pit was not needed and one operator could handle the joining of the two assemblies.