Читать книгу Speechless - Tom Lanoye - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление-

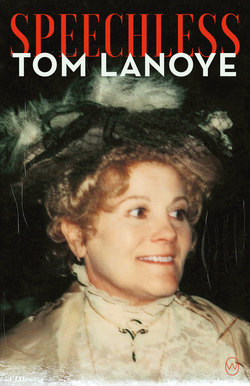

BUT DON’T BE fooled. I’m now talking again, jumping from one thing to another, sorry, about that photo on the front cover. It’s not because that hat suits my mother—[she] ‘All my life it’s been like that, give me a hat and I look good in it, whether it’s a flower pot or a flying saucer’—that in daily life she was often discovered wearing headgear. Certainly not such a striking specimen.

She preferred a simple hairband when she was sweaty and, well into old age, was unashamedly at work in a swimming costume in the vegetable garden of her allotment. Our summer house, which we had built ourselves, called ‘the bungalow’, or else ‘our bungalow’, was located a stone’s throw from the centre of her and my birthplace, which was once promoted from an insignificant commune to a proper town by none other than Napoleon. He was already emperor at the time.

Since then Sint-Niklaas has acquired the greatest number of secondary schools in the whole area, the highest suicide rate in the country, and the largest market square—if you like, the largest empty space—in the whole of Europe.

In order to make up for everything, the emptiness as well as the suicidal thoughts, there rises once a year on that huge, empty market square, in commemoration of the Liberation—a term that awakens in the inhabitants increasingly new meanings and desires—a squadron of gaudy balloons, filled with helium or freshly baked hot air.

The latter, the modern hot-air balloons, are first rolled out on the ground by three or four balloonists at a time. An unrecognizable jumble that looks like a granny knot tied by giants is expertly disentangled and unfolded into a plastic puddle, capricious and crinkled, in which nevertheless the contours are discernible of the weird balloon shape that is about to astonish us. Or will it be another of those humdrum ones? One of those pears hanging upside down, as multicoloured as a beach ball with delusions of grandeur?

With lots of hissing and roaring a jet of flame shoots out of a burner which, together with a large fan, is incorporated in a frame that in turn is mounted on top of the balloon basket. For now that basket is lying pathetically on its side. The fan, sideways and rather lazily, directs the jet plus a first stream of hot air into the opening of the balloon. It has to be held open by the balloonist and his helpers. They stand on tiptoe, arms high above their heads, grabbing hold of the slippery edge of the opening with both hands and making sure that that they themselves don’t get caught in the stream of hot air, on pain of having at least their eyelashes and eyebrows singed off, and usually also every hair on their head. One has to make sacrifices for one’s hobby.

Behind their backs a colossus gradually takes shape, then stands up jerkily, as if after a barbaric open-air childbirth. It raises first its head, then its back, then its upper body. Slowly and majestically it seems to sprout from the ground itself, yes, it springs from our market square in slow motion, surrounded solely by brothers, as if it were one of the countless earth-born warriors which rose from the field that Jason had sown with dragon’s teeth and which he would have to defeat in order to capture the Golden Fleece. In exactly the same way, overpowering and threatening, the modern supermen swell into view, ever fuller, ever higher, until they have clambered completely upright, pulling the basket straight beneath them, their first triumph. Their jets of flame sing louder and more love-struck the more powerful and mightier they become, and look, there they stand finally fully grown, waving the plumes of their helmets, in a neat row: our gentle mastodons, swaying in our inevitable autumn breeze, trembling with expectation as is appropriate after a birth, for the time being still restrained by cables like Gulliver by the Lilliputians, but ready to make an irresistible leap up to the heavens. A contemporary army consisting mainly of figs hanging upside down—they don’t always have to be pears—in all the gaudiest colours of the rainbow. There are also some in the shape of a gingerbread house or a Smurf. There is even a crate of beer of a well-known brand which is also the sponsor of the feather-light monster, since someone has to pay the bills, even those for hot air.

A little later they climb into the sky magnificently and to loud applause. The scarce helium balloons, caught in fishnets with too large a mesh, just as a female buttock can be squeezed into a saucy stocking, quickly jettison some ballast—bags of river sand, bags of loam. That is: the contents of the bags are scattered to the four winds with exaggerated gestures, in a ritual reminiscent of the ancient sower who still adorns the cover of our school exercise books, although paradoxically no grain is sown, just sand. Sand on stone, sand on emptiness, sand on people, sand on sand.

It dissipates immediately, to the relief of the upward-looking spectators, since in extreme emergencies, for example to avoid a pylon, it is permitted to offload the sand with bag and all, at the risk of hitting a back-up car or an unsuspecting bovine or occasionally an unfortunate walker, and one disastrous year even, in order to avoid the sharp rake of a television aerial, a pram, thank God empty—the little passenger had just been taken out to peer, holding Daddy’s hand, at the Smurf floating above them, and the next instant, right next to them: splat! A sandbag, slap in the middle of the pram, whose wheels flew off at the impact.

The hot-air balloons on the other hand, fizzing angrily, suck in an extra long burner flame through their clearly visible arseholes. A reverse fart that, even more in reverse, gives them an upward jerk, toward the wide firmament. In this way our helium globes and our hot-air giants rise in brotherly fashion above our two central church towers, one of which bears a gigantic gilded statue of the Virgin Mary instead of—as would be fitting, in accordance with our legendary Flemish national character, which bursts with modesty—a discreet weathervane or a sluggish dragon, one of those scaly monsters that enjoys being routed by the archangel Michael.

However, the people of Sint-Niklaas are not known for their discretion or modesty. As a result their Mary does not look as if she will ever permit herself to be routed, and certainly not with enjoyment, not even by an archangel. She is as high as two houses, our Mary, wears a crown on her head and carries a child on her arm. Our Holy Mary as a fertile empress armoured from head to toe in shiny gold leaf. Consequently she is popularly known as Gilt Mary. When there is sufficient mist, despite all the gold leaf, to remove her from sight, the popular sneer is that Gilt Mary is on her travels again, and that she can well afford it, with all that precious metal and all her spare time, because only one child? You can hardly call that a time-consuming task, hardly even a family. One is none.

Today there is no mist, far from it, there is a slight rain of fine sand, but apart from that it is a brilliant Sunday in September, and the colours are as unruly and shiny as in a Breughel painting, the ordinary people cheer and drink and eat hamburgers with fried onion rings and fresh tomato sauce, while—above the festive stalls and the chewing chops—a squadron of airships takes to the sky. They rise above our chimneys and slates, above our fashionable roof terraces and densely populated balconies packed with waving local celebrities. They brush past many gables belonging to cafés with names like De Graanmaat and Hemelrijck, or shops with names like Weduwe Goethals & Dochters, where they sell crystal glasses and cutlery boxes lined with blue silk, and of a chip shop called Putifar, after the circus donkey in a children’s book.

They shoot upward, past the front of our relatively recent town hall, upward past the façade of our ancient jail—a former prison which in your childhood served as, what symbolism, a library, and which they shortly plan, what a sign of the times, to convert into lofts, just as they want to convert everything into lofts nowadays, even former libraries where you were once able to wreck your eyesight reading books, without a moment’s regret, and where at a certain moment there wasn’t one book left, according to your age category, for you to read, and where the librarian—may his memory be honoured, his name praised, his bloodline blessed—then gave you permission to start on the books of the next category, on condition that you talked to no one about it, and that was what happened.

They brush past that significant gable, failing by a whisker to pull off the gutter, plus some tiles from the year dot. Then they finally make for the open sky, the boundless heavens, majestic and silent, high above our roofs and courtyards and yet floating away precisely over the great access road on the ground floor, our Parklaan, which, surprise surprise, passes a park and is already jam-packed with hooting pursuit cars whose passengers wish to follow with their own eyes the Calvary of their favourite, secretly hoping for a cautious accident—the year before one landed in a castle moat, three got caught in barbed wire, and two crashed in the Westakkers military zone, almost resulting in an international emergency, since we are talking about the heyday of the Cold War.

At the end of this Parklaan, right above the busy junction with the secondary motorway from Antwerp to Ghent, the aerial flotilla seems becalmed for a moment. Just for a second the inverted pears and figs and plump women’s buttocks just hang there hesitantly in the air, dangling like Christmas baubles without a tree. Then they resolutely choose a course. Not toward Ghent or Antwerp. Not to Hulst in Holland, but to Temse on the Scheldt. In so doing they first float past the local shopping mall, the Waasland Retail Centre, which when it was created seemed like a good idea with its ample parking facilities and covered shopping arcades, but which for years has been sucking the life out of the town centre like a tapeworm sucks the libido out of a prize pig that was nevertheless intended to provide semen for the whole region during its lifetime. And then at last, and with my apologies again for the long digression this time, but that’s how I’m made, that’s how people tell stories and commemorate in my area and in my family, that’s what our language is like, what our flesh is like, expansive. We’ll have to learn to live with it, you and I, at least for the duration of this saga, but so be it—after that Retail Centre, the balloons float above a section of green suburbia where, according to tradition and semantics, a patch of bog once lay that was noted for its population of frogs. It is still called the Puytvoet, but it must have been drained over the course of time, although the meadows and fields and football pitches of The White Boys FC are still convex in shape in order to facilitate the run-off of the generous precipitation for which our Low Countries are so renowned.

The streams of the Puytvoet are deeper and more numerous and every few metres boast a specimen of our beloved moisture absorber, our drainage soldier: the pollard willow, from which in earlier times we carved our clogs. The dirt paths too, the potholes and edges of which we have tried for years to repair with rubble and ashes from our stoves—a week later they have disappeared, like every kind of hard core, from half-sleepers to sections of wall, you name it, everything is swallowed up by our insatiable earth, which with its restless jaws can grind up a cosmos, from cat litters to skeletons, from coachwork to clapped-out pianos—those earth paths too then are lined, on both sides indeed, with water vacuum cleaners.

But these are slender sisters of the pollard willows which we call Canada willows and which, elegantly and supply and lithely rustling, wave their crowns and their silver leaves at the fleet of balloons high above them.

And there, finally, on the ground among the pollard willows and those Canada willows, in a plot carved out by streams and dirt paths, yes there, over there in her vegetable garden in her favourite swimsuit, black with a white pattern, looking up with one hand over her eyes, in her bare feet by a modest bonfire of dried potato tops—there she is. With that band in her hair.

She looks reflective or admiring, it is not clear which. Perhaps she is listening to the roaring song of the burners, a jubilant choir up above. Or perhaps she is just following the coiling veil of smoke twirling from her own fire to where it dissipates into nothing.

Or perhaps she is measuring one of the balloons with the naked eye, wondering how many evening dresses a skilful seamstress could conjure up out of it if there were yet another costume piece in the programme, Le Malade imaginaire or L’Avare—‘there’s always a demand for Molière, at the box office at least’.

A reflective woman in a vegetable garden, beneath a firmament of fabulous beasts, on a Sunday in September. A multicoloured and strangely soothing spectacle.

At least if there isn’t a storm and it doesn’t rain cats and dogs and the whole thing doesn’t have to be postponed until next year’s Liberation celebrations.

But a promise is a promise: this must not and will not be about balloons in the shape of figs or a crate of beer, but about my mother and her unacceptably cruel end. I have run away from this book for long enough, novel or no novel. It should have been written much earlier. Allow me a timeout to explain that to you. It will not, I promise you, be a delay. On the contrary, it forms part of the mourning process, at a time and in a community that has lost the ability to mourn. The lament no longer has a raison d’être. Sorrow must either be suppressed or lead to something productive.

And I am an obedient bastard of those two possibilities.

I have dragged my feet and bickered like never before, hiding out of cowardice from a pain that I had swallowed down without digesting it, but also without wanting to digest it. Because before I could abandon them to the great forgetting, my dismay and my pent-up concern, before I could submerge and dissolve in the Lethe of everyday life, I just had to do something with them. I had to convert them, with a click of the fingers pouring gold from lead, mindful of King Midas, because I can do that now, I told myself, ‘make something out of nothing’, capture something for ever, although only on patient paper. It’s all I’m good for. From mud to marble in no time at all.

Yet I still couldn’t start. A prey to continuing grief as if to a lung disease—I stood feeling dizzy in department stores and gyms, in bookshops and on literary platforms—I began to feel increasingly ashamed of my creative indecision, resulting in still more indecision. King Midas? Jonah, biting his nails in the innards of his whale. Job, idly fretting on his glorious rubbish dump. The urge to act paralysed by a thousand questions. I have to restrain myself, with the catalogue of Western art history in my hand, not also to resort to Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. That would be, apart from ridiculous, another flight, yet another postponement. Whoever hunts for comparisons is detaching themselves from reality, from the awareness of how overwhelmingly ordinary it is, but also how unknowable and devastatingly unique. No greater swindle than the knowledge of art. Job and Jonah have no place here, let alone Hamlet and the rest of the sluttish international crew of the good ship Culture, that international floating escort bureau which provides a value-adding strumpet for every aspiration and every swoon. Stop the make-up and hair-curling, stop posing, as King Oedipus or the Good Soldier Schweik, Sancho Panza or his boss. It’s about you and you alone. I mean: about me. That is precisely the point. Why should I suddenly have to write this book? There are enough people with deceased mothers, most of whom have had more spectacular careers than that of a butcher’s wife from Waasland. No shortage of heavyweight women, with brilliant children and a life set in Mumbai or New York, Rome or Rio, instead of a Flemish hellhole. Let such fortunate orphans get to work. Let them grieve and honour and fête memories, in a geographical and historical framework that the reader does not first have to look up in the tiniest corner of his encyclopedia.

Let them glory. Not me.

The greatest pressure did not even come bubbling up from myself. From beyond the grave I could feel her pressure. Mothers never become human beings again, mothers remain mothers.

I saw the corner of her mouth and her eyebrow once more curling in disdain, her burning filter cigarette was again balancing between two fingers, and she herself was looking away—silent for a change, absolutely silent, ear-shatteringly silent, speechless with feigned indignation, as a grand tragédienne scarcely one metre sixty tall, acting her fathomless disappointment, displaying her displeasure at her youngest child every day that he did not write her story.

‘If I feel contempt for any kind of person, it’s those who speak ill of their parents.’ How many times she said that to me! True, after she had come to terms with the fact that I was becoming a writer, counter to her express wish and preference. [she, the first time she heard of my plans] ‘Writing is something for lazy people, drunkards and paupers.’ A few years later she sat in the pitch darkness, glowing with pride that I turned out to be able to live from my pen, won a literary prize, and after all had no drink problem. ‘I always knew. About those prizes. He’s got more in him than he thinks.’ She said that in my presence as if I were not there. Making no secret of the fact that she must have had a decisive part to play. ‘Like mother, like son.’ That is the essence of all text, certainly when spoken aloud: the most important thing is the subtext.

Sometimes, though, the text and the subtext simply merge. How often she longed quite openly, certainly after the appearance of my first collection of stories, with a photo of my father on the cover, for me to write more about her? But at the same time delicately warning me that it would be better if I produced a grand and positive story, a tome of fitting length, not a malicious memo. Noblesse oblige, after her double life motto, ‘You must not spit in the spring from which you have drunk’ and ‘You’ve got more in you than you think.’

The latter should be taken literally. There is more in you. Yes, in you too. In all of us. Lots more. More and more. ‘Of course you passed your exams with distinction! [she, rolling her eyes] That’s only normal, isn’t it? You could also have done it with the highest distinction. Oh God, a person can’t have everything. See it from the positive side. Now you’ve got something else to look forward to. When are your next tests?’ Does a human being ever become any more than that? The repetition of the same test, in ever-different forms, if need be that of a book. If need be this book. A classic biography which at the same time must have nothing classic about it, which on the contrary must produce something extraordinary. ‘Oh yes! [she, with one hand held triumphantly above her head] Something original! Something spiritual! You have a completely free choice. As long as it’s something that makes everyone say: it surprised us cruelly, but affected us deeply. We’d never thought Lanoye had it in him.’

While not writing I became aware of her ever-growing expectation that was not an expectation but a demand, a claim, a constitutional right, fed by her pretensions as an amateur actress, her lifelong dormant disillusion at being a butcher’s wife against her will and her equally lifelong arsenal of the feminine tyrant, not used to not getting her way.

For oh my God in whom I don’t believe—how perfectly she mastered the palette of domestic extortion! It usually won her respect, sometimes horror, and always obedience, regardless of her choice of weapon, always adapted to the terrain and the position of the family battle. Her armoury was full and the weapons adequately oiled. Little white lie alongside punitive threat. Offended silence alongside a furious torrent of words. Working in a whisper on private sentiment alongside pointing sarcastically at the approaching mockery of the whole neighbourhood and the whole school and the whole country. No role was beneath her, no retort too refined. ‘There’s only one kind of people who are more abominable than those who write bad things about their parents. They are the people who don’t write about their parents. Though they can write.’

Admittedly she never made that last comment. But she could have. She would say it, without compunction, if she were reading over my shoulder now. Correction, she is reading over my shoulder. Has been the whole time. She is even losing patience because there’s been more about balloons and myself than about her.

And, reading over my shoulder, she says in a throwaway tone but loud enough for me to hear—subtle acting it’s called, her forte, both on the boards and in everyday life—although it must not go unrecorded that she excelled equally in ‘giving people a piece of her mind’—so she says, reading over my shoulder, here and now: ‘And meanwhile it’s still all about you, you know. Anyway, lucky that you’re not reading it aloud. Because dear, oh dear … Where on earth do you still get that ugly “a” of yours from? In a small circle of friends I can understand it, people from Sint-Niklaas together. Or in the shop, when you’re chatting with your customers. Good people, most of whom have never read a serious book, and have trouble with a paper. You have to talk to them in patois, or they’ll think you’re putting on airs, and they’ll go to someone else for their meat. But someone like you? On the radio, on TV, on the platform … Have you ever heard yourself? You didn’t get it from me. Okay, if I have to play the maid in a country farce, then I sometimes use dialect. I like it. I can do it. Or for the old mother in The Van Paemel Family, poor dear. There dialect is moving and appropriate. But surely not with you? A writer, who is supposed to set a good example. How on earth did you ever stagger your way to your degree in Germanic philology? No one can understand. Sometimes I can’t myself.’

Let her read over my shoulder as much as she likes, let her make comments into the bargain, even she will have to put up with my first writing a few pages about myself, because I haven’t finished with that—on we go—paralysed nail-biting in my whale, that indecisive fretting on top of my mountain of compelling material. Its weight does not rest under my backside. It weighs on my chest, while I type this and this and this.

Why is it only my stories that will have to replace her, now she herself has gone? Why not those countless other stories of those who knew her? Daughter, sons, grandchildren, all those remaining relatives—an expanding list, an upside-down bread tree of bloodlines? Plus all her friends and protégés, because she had them, by the score—what would a diva of life be without an ample and loyal public in the only true arena, that of reality? What is a matriarch worth without some additional children outside her own family—orphans, rejected scions? Old friends, schoolmates even, for ever loyal, until death do you part?

Whatever I serve up here, in whatever order, or in whatever key, it will remain a noble lie, a splinter of the prism that was her life. Why should my one limited ray of light be worth more than the sum of all the others put together? My version of the fact of her life is perhaps doomed eventually to be the only one remaining, and hence will be all that is truly left of her. But at least, I hope, for a few years, a decade, perhaps two—what is the duration of a book in an age that seems to be turning away from books? But even then: for those few years, that decade, her voice will still sound, her star will shine, only through me. Why? Because I am the only one who spends my days weighing words and arranging sounds?

You can’t call that awareness an injustice, but for a long time it had a dislocating effect. I felt sick with embarrassment and downright rage in advance at the pretension, the polite predation that dares to call itself ‘literature’—that bloodsucking monster that vegetates on the lives of all those unfortunate enough to find themselves in the proximity of anyone who imagines he is a writer, himself included. Nothing is safe, everything is usable, the distortions in his memory, the fabrications from his neighbourhood, the gossip from his paper, and eventually everything seems only to have happened to provide him with excellent material, even the death of his own mother. Anyone who writes is a vulture.

I’m prepared to play the vulture as much as you want, but not here. This? This must not and will not become literature. Not here of all places, I beg you, I beg myself: no, not the same old boxes of tricks again, full of culturally correct curlicues and grace notes, full of approved writer’s affectations alongside artistically justified metaphors. I have gone beyond literature with capital letters. And at the same time, believe me, there aren’t enough capital letters and punctuation, there is a lack of hyperbole to sing the praise of the courage of an eighty-year-old woman who, when she realized what was happening to her, simply wanted to die and, when she no longer realized anything, went on living stubbornly, and went on breathing, to the bitter end. There are simply too few syllables to curse the shame of her decline, her unequal struggle. Her fate, and in her fate that of everyone.

That’s why this must have nothing to do with literature, and at the same time it must be an improvement on the Bible, an immortal poem such as has never been composed. A militant ode, lofty and compelling and merciless, as if for the most fertile and toughest of all summers. And yet, at the same time, adamantly: a dry account, a list of scenes and tableaux, stripped of frippery and pretensions, quite simply ‘life as it is’, imperfect, fragmented and chaotic.

Nothing but capital letters and booming internal rhymes, and at the same time just naked facts. Nothing and everything at the same time, and preferably vomited up in one gush.

So get writing.

Or not.

First I compiled an anthology of my essays and reviews. Reworking them so thoroughly that I might as well have rewritten them entirely. Not a soul noticed the difference. Meanwhile I had anyway been nicely and meaningfully employed. I had gained six months, another half a year. Cowardice as easy-going self-deception.

I wrote two evening-filling plays, one of them actually in alexandrines from start to finish, to make it extra-entertaining, telling myself that I absolutely had to finish them both first and that in addition they made the perfect preparation for this book, this hard eulogy, that would be everything and nothing at the same time, written in a single gush, novel or not.

I was wrong.

High-minded cowardice.

Transparent deception.

I went to a stomach specialist and lay on my side in order, with the aid of a rubber intestine, to allow a sophisticated garden hose with a miniature lamp and a camera mounted on it to look deep into my innards via my oesophagus. Intestine to intestine, pipe to pipe. A person is only a machine with washers that wear out too quickly.

On my side and half fighting for breath in panic. Because if there is anything I have inherited from her, apart from minor everyday ailments, it is the self-inflicted lacerations of psychosomatic illness, multiplied by this certainty: with the same malady, only the more gruesome of two possible diagnoses can be the correct one.

In the inventory of her body, which shaped mine, there was a primacy of dry coughs and minor complaints. But in her legacy and hence in my thoughts there is only room for afflictions that can vie with those of Egypt. In addition: the work ethic as a caricature. Another neurosis that I hated in her and find in myself—I still don’t know whether she and I possess it thanks to our blanket Judaeo-Christian culture of guilt, or else because of the specific hysteria of the shopkeeping classes. Perhaps this is a combination and there is a connection, not even that crazy, between a neighbourhood shop and a woodland chapel, a butcher’s shop and a synagogue, a boutique and a cathedral. Anyway, every time I don’t do what I think I should—correction: whenever I don’t do something fast enough that I have undertaken to do, just like a computer that writes and loads and reloads its own programmes until it short-circuits—every time, then, that according to my subconscious I fall short of the image I want to project of myself, my right eyelid starts trembling (guaranteed: the final stage of a tumour), my wrists and my shoulders tighten up (guaranteed: multiple sclerosis), my fingertips seem to become lifeless, they tingle and flake (it won’t be leprosy, but still something ghastly).

I get up with a headache and I go to bed with diarrhoea and meanwhile my stomach produces enough sulphuric acid to scorch irreparable holes in its own wall, just as cigarettes smoked the wrong way round would hiss and make holes in a palate. At least that’s what it felt like, the day I decided to call that specialist. That morning I had rolled out of bed and crawled to breakfast on my knees, reduced to the state of a reptile by abdominal pain. One mouthful of coffee and I turned into the foetus of a reptile, made up of contractions and cramps.

Over the telephone the specialist gave me a concise diagnosis that was intended to reassure me, but that in the few hours that separated our telephone conversation from his physical examination transformed into an imaginary life-and-death struggle.

I remembered the natural remedy with which she always combated her stomach acid. (‘Acid? [she, with a dismissive gesture] I’ve got a gastric hernia, nothing can be done about that, it’s to do with my weak spine and your difficult birth.’) You peel a raw potato, chew each slice at length and keep swallowing the mash without drinking anything.

It has to be said: some relief could be detected. The reptile foetus unrolled, sat down on a chair at his laptop and typed in the word that the specialist had repeated five times. Reflux. Twelve million hits. One referring to a Scandinavian hard-rock band with undoubtedly appropriate music. All the others referred in every language on the planet to the symptoms of the phenomenon itself. Because the entrance to your stomach no longer shuts properly, your mouth feels stiff from morning till night, it is as resistant as dried-out leather because of the acid that creeps up during the day like vermin up a drainpipe and that at night laps against your tonsils thanks to the principle of communicating vessels—from stomach to mouth and back again.

And indeed, my tongue felt like the peeling tongue of an old shoe. My teeth, my pride—at almost every check-up my dentist sighs that my teeth will take me to 100—those once indestructible teeth suddenly felt brittle, vulnerable as china that has been washed too often, dry like after eating unripe cherries. Unless something were done quickly, my teeth, destined one day to crack walnuts and open bottles of beer for my 100-year-old companions, but now bathed daily in vitriol of my own making, would have only a few years to go before they split, crumbled, became inflamed, turned black, stank, fell out all by themselves, were pulverized and blown away. Apart from that—some sites predicted, as always mercilessly objective—the chance of throat cancer was scarcely a risk, it was a certainty, and that Adam’s apple wouldn’t last much longer either.

‘You have some scar tissue at the top of your oesophagus and also at the mouth of your stomach,’ mumbled the specialist, peering at his monitor, pushing the garden hose with the lamp and camera attached to it deeper and deeper inside me, as if it were an endless adder that would freely wind its way inside—I was sweating like a trapeze artist who, during a daring new act in the ridge of the tent, is clinging only to precisely that one mouthpiece, with precisely those teeth—‘but apart from that I can’t see much that is spectacular. Losing a few kilos wouldn’t hurt you. I can prescribe you some stomach acid inhibitors, but more exercise and less wine will get you just as far.’ At my insistence he took a few more samples from my stomach wall, to check whether I wasn’t cultivating a handful of open sores, and actually mainly to confirm what I already strongly suspected. I had at least terminal stomach cancer.

The head of the endless adder turned out to contain, besides a lamp and a camera, a pair of forceps, three steel teeth that moved toward each other to grab and extract a piece of my stomach. I became aware of it. Something was gnawing at me, from inside. A death-watch beetle, a rotting space creature, a caterpillar leaving the cocoon, a just desert—something was nibbling at my guts. I had not felt the intestine itself, you have to drink an anaesthetic beforehand, probably distilled from the poison of a bird spider, which anaesthetizes your oesophagus so heavily that afterwards you mustn’t eat or drink anything for an hour, or else everything will literally go down the wrong way, toward the lungs. Before you know it you’ll be drowning in a cup of tea.

I didn’t drown, I was simply hollowed out. I was still lying on my side, I was still biting desperately on the mouthpiece, as if I was hanging on to life itself, spinning through in the roof beams of our universe, sweating like a cheese round in the sunlight, with fanatically closed eyes—and yet I saw before me how, deep inside me, an endless mechanical snake, a monster with a Cyclops’ eye and a miner’s lamp on its head, started pinching bits of my stomach. I felt its clawing trident snipping around, at random, and I recognized it, dammit, I recognized the insatiable trident.

I recognized it twice.

We once had at home—how old was I? Five? Seven?—a pair of sugar tongs that I could not stop playing with. A silver-plated hollow stick with a button on one side, and when you pressed it on the other side exactly the same kind of primitive claw opened as the one now gnawing at my stomach, eating what was supposed to digest my food. Picking, nipping—a humming bird fighting a closed, carnivorous plant.

With the silver-plated tongs you picked up a cube and deposited it in a cup. I did it so often not because of the sugar but because of the playful delight of those perfect tongs, which were taken away from me every time, on her sighing orders of course, and I got a flea in my ear into the bargain because I wouldn’t listen at once.

I couldn’t locate those tongs after she found her way once and for all and inexorably into the closed institution where she would spend her last few months, among other human wrecks—carcasses with limited movement capable only of drooling and relieving themselves, most of them lopsided and tied, like her, to their beds, their armchairs, their wheelchairs. After that unwanted separation my father moved by himself into an old people’s home four streets away from her. He left the flat where they had lived for almost two decades that was situated above the butcher’s shop where they had done business for nearly forty years. Virtually none of their household effects could go with him.

For a week I was condemned to the role of arbitrator. I, the liquidator, handing down verdicts on every knick-knack and every heirloom, both equally precious. The archive and register of two intimately interwoven lives, also the backdrop of my childhood, with all the props—it degenerated in my hands into a collection of anonymous things, whether or not usable elsewhere, sometimes with a market value, sometimes distributable, usually to be thrown away. Vanished, wiped out, passé. My father left the decision entirely up to his children, just as in the past he would have left it up to my mother. Apart from photos of her, and his television set, there was nothing that he indicated was necessary for the rest of his existence.

However hard I looked for them, there was no sign of the three-fingered sugar tongs.

As a ten-year-old ringleader I used another claw foot, but larger and yellowy-white, and scaly, and with long horn-like nails, to terrify a girl who lived nearby and was two years older than me. A severed chicken’s claw from our butcher’s shop. I held it in my bunched-up sleeve and advanced on her with a contorted face, grunting, talking gibberish, drooling, swiping with my new limb at her freckle-covered arms and legs.

You could even fish out a tendon with a needle from where the leg had been hacked off and like a puppeteer pull the tendon taut with two fingers so that the chicken’s claw opened and closed again. My little neighbour was already upset, but when she saw my new hand actually moving she started screaming.

A few years later she showed me, in our lock-up garage halfway down the street, where all the car owners in our neighbourhood rented garages, in a maze of gravel paths with rows and rows of long concrete compartments, all the same size, all with pink corrugated sheets and each with a rickety double gate—the complex itself was the limbo area outside a wood yard, which smelt eternally of diesel and pine woods—in the dim light of our lock-up garage, then, my easily frightened neighbour showed me, unsolicited, her pristine tits. Two swollen nipples actually, already deeply dark, that was true, silky and yet recalcitrantly stiff, the flesh around the areola lightly accentuated and as white as the cap of a freshly picked mushroom, but with freckles. ‘They’re going to be very big,’ she whispered, ‘later, like my sister’s. Have a feel.’

And I felt, honoured and bewildered. I plucked and picked, not with the aid of a dead chicken’s foot, but with three cautious fingers of my own, a mouth of fingertips, which sucked at her soft deep dark expectancy, first left then right, and the more I plucked and sucked, the more resistant her soft mushroom caps with their freckles became, the more she sighed in my face, closer and closer.

A smell I didn’t yet know, something halfway between milk and almonds, dispelled the diesel and pine woods around me.