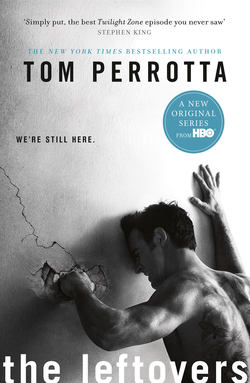

Читать книгу The Leftovers - Том Перротта - Страница 8

HEROES’ DAY

ОглавлениеIT WAS A GOOD DAY for a parade, sunny and unseasonably warm, the sky a Sunday school cartoon of heaven. Not too long ago, people would have felt the need to make a nervous crack about weather like this—Hey, they’d say, maybe this global warming isn’t such a bad thing after all!—but these days no one bothered much about the hole in the ozone layer or the pathos of a world without polar bears. It seemed almost funny in retrospect, all that energy wasted fretting about something so remote and uncertain, an ecological disaster that might or might not come to pass somewhere way off in the distant future, long after you and your children and your children’s children had lived out your allotted time on earth and gone to wherever it was you went when it was all over.

Despite the anxiety that had dogged him all morning, Mayor Kevin Garvey found himself gripped by an unexpected mood of nostalgia as he walked down Washington Boulevard toward the high school parking lot, where the marchers had been told to assemble. It was half an hour before showtime, the floats lined up and ready to roll, the marching band girding itself for battle, peppering the air with a discordant overture of bleats and toots and halfhearted drumrolls. Kevin had been born and raised in Mapleton, and he couldn’t help thinking about Fourth of July parades back when everything still made sense, half the town lined up along Main Street while the other half—Little Leaguers, scouts of both genders, gimpy Veterans of Foreign Wars trailed by the Ladies Auxiliary—strode down the middle of the road, waving to the spectators as if surprised to see them there, as if this were some kind of kooky coincidence rather than a national holiday. In Kevin’s memory, at least, it all seemed impossibly loud and hectic and innocent—fire trucks, tubas, Irish step dancers, baton twirlers in sequined costumes, one year even a squadron of fez-bedecked Shriners scooting around in those hilarious midget cars. Afterward there were softball games and cookouts, a sequence of comforting rituals culminating in the big fireworks display over Fielding Lake, hundreds of rapt faces turned skyward, oohing and wowing at the sizzling pinwheels and slow-blooming starbursts that lit up the darkness, reminding everyone of who they were and where they belonged and why it was all good.

Today’s event—the first annual Departed Heroes’ Day of Remembrance and Reflection, to be precise—wasn’t going to be anything like that. Kevin could sense the somber mood as soon as he arrived at the high school, the invisible haze of stale grief and chronic bewilderment thickening the air, causing people to talk more softly and move more tentatively than they normally would at a big outdoor gathering. On the other hand, he was both surprised and gratified by the turnout, given the cool reception the parade had received when it was first proposed. Some critics thought the timing was wrong (“Too soon!” they’d insisted), while others suggested that a secular commemoration of October 14th was wrongheaded and possibly blasphemous. These objections had faded over time, either because the organizers had done a good job winning over the skeptics, or because people just generally liked a parade, regardless of the occasion. In any case, so many Mapletonians had volunteered to march that Kevin wondered if there’d be anyone left to cheer them on from the sidelines as they made their way down Main Street to Greenway Park.

He hesitated for a moment just inside the line of police barricades, marshaling his strength for what he knew would be a long and difficult day. Everywhere he looked he saw broken people and fresh reminders of suffering. He waved to Martha Reeder, the once-chatty lady who worked the stamp window at the Post Office; she smiled sadly, turning to give him a better look at the homemade sign she was holding. It featured a poster-sized photograph of her three-year-old granddaughter, a serious child with curly hair and slightly crooked eyeglasses. ASHLEY, it said, MY LITTLE ANGEL. Standing beside her was Stan Wash-burn—a retired cop and former Pop Warner coach of Kevin’s—a squat, no-neck guy whose T-shirt, stretched tight over an impressive beer gut, invited anyone who cared to ASK ME ABOUT MY BROTHER. Kevin felt a sudden powerful urge to flee, to run home and spend the afternoon lifting weights or raking leaves—anything solitary and mindless would do—but it passed quickly, like a hiccup or a shameful sexual fantasy.

Expelling a soft dutiful sigh, he waded into the crowd, shaking hands and calling out names, doing his best impersonation of a small-town politician. An ex–Mapleton High football star and prominent local businessman—he’d inherited and expanded his family’s chain of supermarket-sized liquor stores, tripling the revenue during his fifteen-year tenure—Kevin was a popular and highly visible figure around town, but the idea of running for office had never crossed his mind. Then, just last year, out of the blue, he was presented with a petition signed by two hundred fellow citizens, many of whom he knew well: “We, the undersigned, are desperate for leadership in these dark times. Will you help us take back our town?” Touched by this appeal and feeling a bit lost himself—he’d sold the business for a small fortune a few months earlier, and still hadn’t figured out what to do next—he accepted the mayoral nomination of a newly formed political entity called the Hopeful Party.

Kevin won the election in a landslide, unseating Rick Malvern, the three-term incumbent who’d lost the confidence of the voters after attempting to burn down his own house in an act of what he called “ritual purification.” It didn’t work—the fire department insisted on extinguishing the blaze over his bitter objections—and these days Rick was living in a tent in his front yard, the charred remains of his five-bedroom Victorian hulking in the background. Every now and then, when Kevin went running in the early morning, he would happen upon his former rival just as he was emerging from the tent—one time bare-chested and clad only in striped boxers—and the two men would exchange an awkward greeting on the otherwise silent street, a Yo or a Hey or a What’s up?, just to show there were no hard feelings.

As much as he disliked the flesh-pressing, backslapping aspect of his new job, Kevin felt an obligation to make himself accessible to his constituents, even the cranks and malcontents who inevitably came out of the woodwork at public events. The first to accost him in the parking lot was Ralph Sorrento, a surly plumber from Sycamore Road, who bulled his way through a cluster of sad-looking women in identical pink T-shirts and planted himself directly in Kevin’s path.

“Mr. Mayor,” he drawled, smirking as though there were something inherently ridiculous about the title. “I was hoping I’d run into you. You never answer my e-mails.”

“Morning, Ralph.”

Sorrento folded his arms across his chest and studied Kevin with an unsettling combination of amusement and disdain. He was a big, thick-bodied man with a buzz cut and a bristly goatee, dressed in grease-stained cargo pants and a thermal-lined hoodie. Even at this hour—it was not yet eleven—Kevin could smell beer on his breath and see that he was looking for trouble.

“Just so we’re clear,” Sorrento announced in an unnaturally loud voice. “I’m not paying that fucking money.”

The money in question was a hundred-dollar fine he’d been assessed for shooting at a pack of stray dogs that had wandered into his yard. A beagle had been killed on the spot, but a shepherd-lab mix had hobbled away with a bullet in its hind leg, dripping a three-block trail of blood before collapsing on the sidewalk not far from the Little Sprouts Academy on Oak Street. Normally the police didn’t get too exercised about a shot dog—it happened with depressing regularity—but a handful of the Sprouts had witnessed the animal’s agony, and the complaints of their parents and guardians had led to Sorrento’s prosecution.

“Watch your language,” Kevin warned him, uncomfortably aware of the heads turning in their direction.

Sorrento jabbed an index finger into Kevin’s rib cage. “I’m sick of those mutts crapping on my lawn.”

“Nobody likes the dogs,” Kevin conceded. “But next time call Animal Control, okay?”

“Animal Control.” Sorrento repeated the words with a contemptuous chuckle. Again he jabbed at Kevin’s sternum, fingertip digging into bone. “They don’t do shit.”

“They’re understaffed.” Kevin forced a polite smile. “They’re doing the best they can in a bad situation. We all are. I’m sure you understand that.”

As if to indicate that he did understand, Sorrento eased the pressure on Kevin’s breastbone. He leaned in close, his breath sour, his voice low and intimate.

“Do me a favor, okay? You tell the cops if they want my money, they’re gonna have to come and get it. Tell ’em I’ll be waiting for ’em with my sawed-off shotgun.”

He grinned, trying to look like a badass, but Kevin could see the pain in his eyes, the glassy, pleading look behind the bluster. If he remembered correctly, Sorrento had lost a daughter, a chubby girl, maybe nine or ten. Tiffany or Britney, a name like that.

“I’ll pass it along.” Kevin patted him gently on the shoulder. “Now, why don’t you go home and get some rest.”

Sorrento slapped at Kevin’s hand.

“Don’t fucking touch me.”

“Sorry.”

“Just tell ’em what I told you, okay?”

Kevin promised he would, then hurried off, trying to ignore the lump of dread that had suddenly materialized in his gut. Unlike some of the neighboring towns, Mapleton had never experienced a suicide by cop, but Kevin sensed that Ralph Sorrento was at least fantasizing about the idea. His plan didn’t seem especially inspired—the cops had bigger things to worry about than an unpaid fine for animal cruelty—but there were all sorts of ways to provoke a confrontation if you really had your heart set on it. He’d have to tell the chief, make sure the patrol officers knew what they were dealing with.

Distracted by these thoughts, Kevin didn’t realize he was heading straight for the Reverend Matt Jamison, formerly of the Zion Bible Church, until it was too late to make an evasive maneuver. All he could do was raise both hands in a futile attempt to fend off the gossip rag the Reverend was thrusting in his face.

“Take it,” the Reverend said. “There’s stuff in here that’ll knock your socks off.”

Seeing no graceful way out, Kevin reluctantly took possession of a newsletter that went by the emphatic but unwieldy title “OCTOBER 14TH WAS NOT THE RAPTURE!!!” The front page featured a photograph of Dr. Hillary Edgers, a beloved pediatrician who’d disappeared three years earlier, along with eighty-seven other local residents and untold millions of people throughout the world. DOCTOR’S BISEXUAL COLLEGE YEARS EXPOSED! the headline proclaimed. A boxed quote in the article below read, “‘We totally thought she was gay,’ former roommate reveals.”

Kevin had known and admired Dr. Edgers, whose twin sons were the same age as his daughter. She’d volunteered two evenings a week at a free clinic for poor kids in the city, and gave lectures to the PTA on subjects like “The Long-Term Effects of Concussions in Young Athletes” and “How to Recognize an Eating Disorder.” People buttonholed her all the time at the soccer field and the supermarket, fishing for free medical advice, but she never seemed resentful about it, or even mildly impatient.

“Jesus, Matt. Is this necessary?”

Reverend Jamison seemed mystified by the question. He was a trim, sandy-haired man of about forty, but his face had gone slack and pouchy in the past couple of years, as if he were aging on an accelerated schedule.

“These people weren’t heroes. We have to stop treating them like they were. I mean, this whole parade—”

“The woman had kids. They don’t need to be reading about who she slept with in college.”

“But it’s the truth. We can’t hide from the truth.”

Kevin knew it was useless to argue. By all accounts, Matt Jamison used to be a decent guy, but he’d lost his bearings. Like a lot of devout Christians, he’d been deeply traumatized by the Sudden Departure, tormented by the fear that Judgment Day had come and gone, and he’d been found lacking. While some people in his position had responded with redoubled piety, the Reverend had moved in the opposite direction, taking up the cause of Rapture Denial with a vengeance, dedicating his life to proving that the people who’d slipped their earthly chains on October 14th were neither good Christians nor even especially virtuous individuals. In the process, he’d become a dogged investigative journalist and a complete pain in the ass.

“All right,” Kevin muttered, folding the newsletter and jamming it into his back pocket. “I’ll give it a look.”

THEY STARTED moving at a few minutes after eleven. A police motorcade led the way, followed by a small armada of floats representing a variety of civic and commercial organizations, mostly old standbys like the Greater Mapleton Chamber of Commerce, the local chapter of D.A.R.E., and the Senior Citizens’ Club. A couple featured live demonstrations: Students from the Alice Herlihy Institute of Dance performed a cautious jitterbug on a makeshift stage while a chorus line of karate kids from the Devlin Brothers School of Martial Arts threw flurries of punches and kicks at the air, grunting in ferocious unison. To a casual observer it would have all seemed familiar, not much different from any other parade that had crawled through town in the last fifty years. Only the final vehicle in the sequence would have given pause, a flatbed truck draped in black bunting, not a soul on board, its emptiness stark and self-explanatory.

As mayor, Kevin got to ride in one of two honorary convertibles that trailed the memorial float, a little Mazda driven by Pete Thorne, his friend and former neighbor. They were in second position, ten yards behind a Fiat Spider carrying the Grand Marshall, a pretty but fragile-looking woman named Nora Durst who’d lost her entire family on October 14th—husband and two young kids—in what was widely considered to be the worst tragedy in all of Mapleton. Nora had reportedly suffered a minor panic attack earlier in the day, claiming she felt dizzy and nauseous and needed to go home, but she’d gotten through the crisis with the help of her sister and a volunteer grief counselor on hand in the event of just such an emergency. She seemed fine now, sitting almost regally in the backseat of the Spider, turning from side to side and wanly raising her hand to acknowledge sporadic bursts of applause from spectators who’d assembled along the route.

“Not a bad turnout!” Kevin remarked in a loud voice. “I didn’t expect this many people!”

“What?” Pete bellowed over his shoulder.

“Forget it!” Kevin shouted back, realizing it was hopeless to try to make himself heard over the band. The horn section was plastered to his bumper, playing an exuberant version of “Hawaii Five-O” that had gone on for so long he was beginning to wonder if it was the only song they knew. Impatient with the funereal pace, the musicians kept surging forward, briefly overtaking his car, and then falling abruptly back, no doubt wreaking havoc on the solemn procession bringing up the rear. Kevin twisted in his seat, trying to see past the musicians to the marchers behind them, but his view was blocked by a thicket of maroon uniforms, serious young faces with inflated cheeks, and brass instruments flashing molten gold in the sunlight.

Back there, he thought, that was the real parade, the one no one had ever seen before, hundreds of ordinary people walking in small groups, some holding signs, others wearing T-shirts bearing the image of a friend or family member who’d been taken away. He’d seen these people in the parking lot, shortly after they’d broken into their platoons, and the sight of them—the incomprehensible sum of their sadness—had left him shaken, barely able to read the names on their banners: the Orphans of October 14th, the Grieving Spouses’ Coalition, Mothers and Fathers of Departed Children, Bereft Siblings Network, Mapleton Remembers Its Friends and Neighbors, Survivors of Myrtle Avenue, Students of Shirley De Santos, We Miss Bud Phipps, and on and on. A few mainstream religious organizations were participating, too—Our Lady of Sorrows, Temple Beth-El, and St. James Presbyterian had all sent contingents—but they’d been stuck way in the back, almost an afterthought, right in front of the emergency vehicles.

MAPLETON CENTER was packed with well-wishers, the street strewn with flowers, many of which had been crushed by truck tires and would soon be trampled underfoot. A fair number of the spectators were high school kids, but Kevin’s daughter, Jill, and her best friend, Aimee, weren’t among them. The girls had been sleeping soundly when he left the house—as usual, they’d stayed out way too late—and Kevin didn’t have the heart to wake them, or the fortitude to deal with Aimee, who insisted on sleeping in panties and flimsy little tank tops that made it hard for him to know where to look. He’d called home twice in the past half hour, hoping the ringer would roust them, but the girls hadn’t picked up.

He and Jill had been arguing about the parade for weeks now, in the exasperated, half-serious way they conducted all the important business in their lives. He’d encouraged her to march in honor of her Departed friend, Jen, but she remained unmoved.

“Guess what, Dad? Jen doesn’t care if I march or not.”

“How do you know that?”

“She’s gone. She doesn’t give a shit about anything.”

“Maybe so,” he said. “But what if she’s still here and we just can’t see her?”

Jill seemed amused by this possibility. “That would suck. She’s probably waving her arms around all day, trying to get our attention.” Jill scanned the kitchen, as if searching for her friend. She spoke in a loud voice, suitable for addressing a half-deaf grandparent. “Jen, if you’re in here, I’m sorry I’m ignoring you. It would help if you could clear your throat or something.”

Kevin withheld his protest. Jill knew he didn’t like it when she joked about the missing, but telling her for the hundredth time wasn’t going to accomplish anything.

“Honey,” he said quietly, “the parade is for us, not for them.”

She stared at him with a look she’d recently perfected—total incomprehension softened by the slightest hint of womanly forbearance. It would have been even cuter if she still had some hair and wasn’t wearing all that eyeliner.

“Tell me something,” she said. “Why does this matter so much to you?”

If Kevin could have supplied a good answer for this question, he would’ve happily done so. But the truth was, he really didn’t know why it mattered so much, why he didn’t just give up on the parade the way he’d given up on everything else they’d fought about in the past year: the curfew, the head-shaving, the wisdom of spending so much time with Aimee, partying on school nights. Jill was seventeen; he understood that, in some irrevocable way, she’d drifted out of his orbit and would do what she wanted when she wanted, regardless of his wishes.

All the same, though, Kevin really wanted her to be part of the parade, to demonstrate in some small way that she still recognized the claims of family and community, still loved and respected her father and would do what she could to make him happy. She understood the situation with perfect clarity—he knew she did—but for some reason couldn’t bring herself to cooperate. It hurt him, of course, but any anger he felt toward his daughter was always accompanied by an automatic apology, a private acknowledgment of everything she’d been through, and how little he’d been able to help her.

Jill was an Eyewitness, and he didn’t need a psychologist to tell him that it was something she’d struggle with for the rest of her life. She and Jen had been hanging out together on October 14th, two giggly young girls sitting side by side on a couch, eating pretzels and watching YouTube videos on a laptop. Then, in the time it takes to click a mouse, one of them is gone, and the other is screaming. And people keep disappearing on her in the months and years that follow, if not quite so dramatically. Her older brother leaves for college and never comes home. Her mother moves out of the house, takes a vow of silence. Only her father remains, a bewildered man who tries to help but never manages to say the right thing. How can he when he’s just as lost and clueless as she is?

It didn’t surprise Kevin that Jill was angry or rebellious or depressed. She had every right to be all those things and more. The only thing that surprised him was that she was still around, still sharing a house with him when she could just as easily have run off with the Barefoot People or hopped on a Greyhound Bus to parts unknown. Lots of kids had. She looked different, of course, bald and haunted, like she wanted total strangers to understand exactly how bad she felt. But sometimes when she smiled, Kevin got the feeling that her essential self was still alive in there, still mysteriously intact in spite of everything. It was this other Jill—the one she never really got a chance to become—that he’d been hoping to find at the breakfast table this morning, not the real one he knew too well, the girl curled up on the bed after coming home too drunk or high to bother scrubbing off last night’s makeup.

He thought about phoning again as they approached Lovell Terrace, the exclusive cul-de-sac where he and his family had moved five years earlier, in an era that now seemed as distant and unreal as the Jazz Age. As much as he wanted to hear Jill’s voice, though, his own sense of decorum held him back. He just didn’t think it would look right, the mayor chatting on his cell phone in the middle of a parade. Besides, what would he say?

Hi, honey, I’m driving past our street, but I don’t see you …

EVEN BEFORE he lost his wife to them, Kevin had developed a grudging sense of respect for the Guilty Remnant. Two years ago, when they’d first appeared on his radar screen, he’d mistaken them for a harmless Rapture cult, a group of separatist fanatics who wanted nothing more than to be left alone to grieve and meditate in peace until the Second Coming, or whatever it was they were waiting for (he still wasn’t clear about their theology and wasn’t sure they were, either). It even made a certain kind of sense to him that heartbroken people like Rosalie Sussman would find it comforting to join their ranks, to withdraw from the world and take a vow of silence.

At the time, the G.R. seemed to have sprung up out of nowhere, a spontaneous local reaction to an unprecedented tragedy. It took him a while to realize that similar groups were forming all over the country, linking themselves into a loose national network, each affiliate following the same basic guidelines—white clothes and cigarettes and two-person surveillance teams—but governing itself without much in the way of organized oversight or outside interference.

Despite its monastic appearance, the Mapleton Chapter quickly revealed itself to be an ambitious and disciplined organization with a taste for civil disobedience and political theater. Not only did they refuse to pay taxes or utilities, but also they flouted a host of local ordinances at their Ginkgo Street compound, packing dozens of people into homes built for a single family, defying court orders and foreclosure notices, building barricades to keep out the authorities. A series of confrontations ensued, one of which resulted in the shooting death of a G.R. member who threw rocks at police officers trying to execute a search warrant. Sympathy for the Guilty Remnant had spiked in the wake of the botched raid, leading to the resignation of the Chief of Police and a severe loss of support for then Mayor Malvern, both of whom had authorized the operation.

Since taking office, Kevin had done his best to dial down the tension between the cult and the town, negotiating a series of agreements that allowed the G.R. to live more or less as it pleased, in exchange for nominal tax payments and guarantees of access for police and emergency vehicles in certain clearly defined situations. The truce seemed to be holding, but the G.R. remained an annoying wild card, popping up at odd intervals to sow confusion and anxiety among law-abiding citizens. This year, on the first day of school, several white-clad adults had staged a sit-in at Kingman Elementary School, occupying a second-grade classroom for an entire morning. A few weeks later, another group of them had wandered onto the high school football field in the middle of a game, lying down on the turf until they were forcibly removed by angry players and spectators.

FOR MONTHS now, local officials had been wondering what the G.R. would do to disrupt Heroes’ Day. Kevin had sat through two planning meetings at which the subject was discussed in detail, and had reviewed a number of likely scenarios. All day he’d been waiting for them to make their move, feeling an odd combination of dread and curiosity, as if the party wouldn’t really be complete until they’d crashed it.

But the parade had come and gone without them, and the memorial service was nearing its close. Kevin had laid a wreath at the foot of the Monument to the Departed at Greenway Park, a creepy bronze sculpture produced by one of the high school art teachers. It was supposed to show a baby floating out of the arms of its astonished mother, ascending toward heaven, but something had misfired. Kevin was no art critic, but it always looked to him like the baby was falling instead of rising, and the mother might not be able to catch it.

After the benediction by Father Gonzalez, there was a moment of silence to commemorate the third anniversary of the Sudden Departure, followed by the pealing of church bells. Nora Durst’s keynote address was the last item on the program. Kevin was seated on the makeshift stage with a few other dignitaries, and he felt a little anxious as she stepped up to the podium. He knew from experience how daunting it could be to deliver a speech, how much skill and confidence it took to command the attention of a crowd even half the size of this one.

But he quickly realized that his worries were misplaced. A hush came over the spectators as Nora cleared her throat and shuffled through her note cards. She had suffered—she was the Woman Who Had Lost Everything—and her suffering gave her authority. She didn’t have to earn anyone’s attention or respect.

On top of that, Nora turned out to be a natural. She spoke slowly and clearly—it was Oratory 101, but a surprising number of speakers missed that day—with just enough in the way of stumbles and hesitations to keep everything from seeming a bit too polished. It helped that she was an attractive woman, tall and well-proportioned, with a soft but emphatic voice. Like most of her audience, she was casually dressed, and Kevin found himself staring a little too avidly at the elaborate stitching on the back pocket of her jeans, which fit with a snugness one rarely encountered at official government functions. She had, he noticed, a surprisingly youthful body for a thirty-five-year-old woman who’d given birth to two kids. Lost two kids, he reminded himself, forcing himself to keep his chin up and focus on something more appropriate. The last thing he wanted to see on the cover of The Mapleton Messenger was a full-color photograph of the mayor ogling a grieving mother’s butt.

Nora began by saying that she’d originally conceived of her speech as a celebration of the single best day of her life. The day in question had occurred just a couple of months before October 14th, during a vacation her family had taken at the Jersey Shore. Nothing special had happened, nor had she fully grasped the extent of her happiness at the time. That realization didn’t strike until later, after her husband and children were gone and she’d had more than enough sleepless nights in which to take the measure of all that she’d lost.

It was, she said, a lovely late-summer day, warm and breezy, but not so bright that you had to think constantly about sunscreen. Sometime in the morning, her kids—Jeremy was six, Erin four; it was as old as they’d ever get—started making a sand castle, and they went about their labor with the solemn enthusiasm that children sometimes bring to the most inconsequential tasks. Nora and her husband, Doug, sat on a blanket nearby, holding hands, watching these serious little workers run to the water’s edge, fill their plastic buckets with wet sand, and then come trudging back, their toothpick arms straining against the heavy loads. The kids weren’t smiling, but their faces glowed with joyful purpose. The fortress they built was surprisingly large and elaborate; it kept them occupied for hours.

“We had our video camera,” she said. “But for some reason we didn’t think to turn it on. I’m glad in a way. Because if we had a video of that day, I’d just watch it all the time. I’d waste away in front of the television, rewinding it over and over.”

Somehow, though, thinking about that day made her remember another day, a terrible Saturday the previous March when the entire family was laid low by a stomach bug. It seemed like every time you turned around, someone else was throwing up, and not always in a toilet. The house stunk, the kids were wailing, and the dog kept whimpering to be let outside. Nora couldn’t get out of bed—she was feverish, drifting in and out of delirium—and Doug was no better. There was a brief period in the afternoon when she thought she might be dying. When she shared this fear with her husband, he simply nodded and said, “Okay.” They were so sick they didn’t even have the sense to pick up the phone and call for help. At one point in the evening, when Erin was lying between them, her hair crusty with dried vomit, Jeremy wandered in and pointed tearfully at his foot. Woody pooped in the kitchen, he said. Woody pooped and I stepped in it.

“It was hell,” Nora said. “That was what we kept telling each other. This is truly hell.”

They got through it, of course. A few days later, everyone was healthy again, and the house was more or less in order. But from then on, they referred to the Family Puke-A-Thon as the low point in their lives, the debacle that put everything else in perspective. If the basement flooded, or Nora got a parking ticket, or Doug lost a client, they were always able to remind themselves that things could have been worse.

“Well, we’d say, at least it’s not as bad as that time we all got so sick.”

It was around this point in Nora’s speech that the Guilty Remnant finally made their appearance, emerging en masse from the small patch of woods flanking the west side of the park. There were maybe twenty of them, dressed in white, moving slowly in the direction of the gathering. At first they seemed like a disorganized mob, but as they walked they began to form a horizontal line, a configuration that reminded Kevin of a search party. Each person was carrying a piece of posterboard emblazoned with a single black letter, and when they got to within shouting distance of the stage, they stopped and raised their squares overhead. Together, the jagged row of letters spelled the words STOP WASTING YOUR BREATH.

An angry murmur arose from the crowd, which didn’t appreciate the interruption or the sentiment. Nearly the entire police force was present at the ceremony, and after a moment of uncertainty, several officers began moving toward the interlopers. Chief Rogers was onstage, and just as Kevin rose to consult him about the wisdom of provoking a confrontation, Nora addressed the officers.

“Please,” she said. “Leave them alone. They’re not hurting anyone.”

The cops hesitated, then checked their advance after receiving a signal from the Chief. From where he sat, Kevin had a clear view of the protesters, so he knew by then that his wife was among them. Kevin hadn’t seen Laurie for a couple of months, and he was struck by how much weight she’d lost, as if she’d disappeared into a fitness center instead of a Rapture cult. Her hair was grayer than he’d ever seen it—the G.R. wasn’t big on personal grooming—but on the whole, she looked strangely youthful. Maybe it was the cigarette in her mouth—Laurie had been a smoker in the early days of their relationship—but the woman who stood before him, the letter N raised high above her head, reminded him more of the fun-loving girl he’d known in college than the heavyhearted, thick-waisted woman who’d walked out on him six months ago. Despite the circumstances, he felt an undeniable pang of desire for her, an actual and highly ironic stirring in his groin.

“I’m not greedy,” Nora went on, picking up the thread of her speech. “I’m not asking for that perfect day at the beach. Just give me that horrible Saturday, all four of us sick and miserable, but alive, and together. Right now that sounds like heaven to me.” For the first time since she’d begun speaking, her voice cracked with emotion. “God bless us, the ones who are here and the ones who aren’t. We’ve all been through so much.”

Kevin attempted to make eye contact with Laurie throughout the sustained, somewhat defiant applause that followed, but she refused even to glance in his direction. He tried to convince himself that she was doing this against her will—she was, after all, flanked by two large bearded men, one of whom looked a little like Neil Felton, the guy who used to own the gourmet pizza place in the town center. It would have been comforting to think that she’d been instructed by her superiors not to fall into temptation by communicating, even silently, with her husband, but he knew in his heart that this wasn’t the case. She could’ve looked at him if she’d wanted to, could’ve at least acknowledged the existence of the man she’d promised to spend her life with. She just didn’t want to.

Thinking about it afterward, he wondered why he hadn’t climbed down from the stage, walked over there, and said, Hey, it’s been a while. You look good. I miss you. There was nothing stopping him. And yet he just sat there, doing absolutely nothing, until the people in white lowered their letters, turned around, and drifted back into the woods.