Читать книгу Woodstock Rising - Tom Wayman - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 2

Evening light remained in the sky as I ambled down Cajon, darted across the highway, and strolled toward Shaw’s Cove. The heat of the day had considerably lessened, so before leaving my place I had slipped on over my T-shirt my usual cool weather attire in the Southland — a Canadian army field jacket. Many people around campus wore pieces of surplus military uniforms, but I guessed I had the only Canadian gear around. The khaki combat jacket displayed my SDS button over the left breast pocket, and a Mao button attached to the right.

As I neared Shaw’s Cove, the barks of the seals were louder, and I could hear the measured, relentless breaking of the surf. Chirping of various birds mixed with the coo-cooing of doves. I took deep breaths, relishing the bouquet of spicy scents from vegetation that crowded the front yards of homes along the streets.

Guantanamero Bay was a rambling wooden house above the beach that Edward and some others had rented the previous year and that Edward had managed to hang on to through the high-rent period of the summer. How the latter feat was accomplished was mysterious, but Edward himself was professionally mysterious. He was a few years older than most of us grad students, which made him twenty-six or twenty-seven. The degree he was pursuing was either in fine arts or anthropology, or maybe some combination. He was difficult to pin down. His favoured attire was Hawaiian shirts, and he may or may not have previously operated an art gallery in Honolulu, depending on what he hinted at different times. “I can neither confirm nor deny my ownership of an art gallery on the Islands,” he would respond when pressed for a definitive answer. He did admit to growing up in Encinitas, north of San Diego.

Edward had dubbed the house Guantanamero Bay, a conflation of the name of the U.S. military base on Cuba, Guantánamo Bay, and the title of the folksong “Guantanamera” made popular by Pete Seeger. The song, Edward had explained once, was based on a poem by the nineteenth-century Cuban revolutionary hero José Martí. No one quite got Edward’s point — was he pro-Cuban, which meant being, like me, pro-Castro and a fan of the late Che Guevara? Edward certainly was anti-war, having participated in a couple of demonstrations that I knew of. Yet he belonged to no peace or radical organizations. He merely smiled his mysterious smile when anyone asked him about his motivation for the name. His sports car, an old English TR-6, boasted a sticker: FIDEL, Sí. CASTRO, NO.

Still, Guantanamero Bay was party central for the group of Irvine grad students I ran with. The large living room at the Bay was made for dancing. I’d hosted a couple of blowouts at my place, but Cajon Street’s front room was about half the size of the Bay’s. Plus I hated cleaning up the spilled beer and wine and chips and salsa and unidentified other goop the morning after. The air inside reeked of cigarette smoke for the next few days, despite open windows and doors.

Wherever the party was, however, we had developed the habit of rocking out until the cops arrived. The Laguna police at the door — always in pairs — invariably explained that whereas their peace could not by law be disturbed, a noise complaint had been duly registered by a neighbour and we had to shut down the music immediately. They never failed to warn that they would not take kindly to having to return a second time on the same complaint. The cops, whether big or average-size, invariably looked like what they probably were — ex-Marines. Their close-cropped hair, large sidearms, and weighty equipment belts clashed fundamentally with the shoulder badges of Laguna’s finest: an artist’s palette. The city regarded itself as an art colony and wanted even its law-enforcement division to reflect this image.

By the time the police showed, one of our group, Alan, a grad student in psychology, would be drunk and belligerent toward anybody he thought was an affront to his dignity. A vital task of the party host was thus to simultaneously mollify the cops and attempt to rein in Alan. Alan was not a large guy, coming up to maybe the middle of the cops’ chests. He wasn’t the Alan Ladd type, either, with his incipient potbelly and a scraggly goatee. But if not headed off, he’d be out on the doorstep prepared to hassle the representatives of law and order about our right to enjoy ourselves and inquiring what kind of person would want to make a living going around bothering people who were simply having fun. The police seemed to regard him as a yappy terrier, and no threat. The risk was that he’d say exactly the wrong thing to a cop having a bad night and provoke some incident that would endanger everybody. Due to the various chemicals being inhaled, swallowed, and snorted at the gathering, the last thing you’d want would be for the police to decide that the situation called for them to enter the premises.

A corollary problem involving Alan was that, if the scene at the door featuring him, the host, and the police went on long enough, certain other party-goers swacked on some legal or illegal substance would stagger forward to see if they could resolve the situation. The worst offender was Myron, one of the English grad students and a pal of Alan’s. A couple of times Myron had insisted on “mediating,” as he put it, between Alan and a cop. In Myron’s alcohol-sodden condition, such intervention simply multiplied the chances of incensing the authorities. Edward was much better than I was at deflecting or muzzling the likes of Alan or Myron while assuring the police that the neighbours’ peace would be promptly restored.

Tense moments at the front door or not, the rear of Guantanamero Bay boasted a large, open covered porch overlooking the cove, a wonderful place to cool out when you were drenched in sweat from a spell of dancing. A path led sharply down below the porch to the sand, a perfect arrangement for slipping off into the moonlight for a while with somebody you intended to get close to. Not that I’d ever done that: mostly I danced with whoever was sitting this one out, except the time I brought Janey to a party. But forgoing use of the beach in this manner didn’t stop me from appreciating the porch as a spot to reduce your body temperature after rocking through several cuts on a Stones album or, a couple of hours into the party, stomping through the full six minutes and thirty seconds of The Doors’ “Light My Fire.”

On a night with a full moon, the view from the porch was itself worth taking a breather to witness. Rows of huge cumulous clouds were often borne in from the Pacific, their puffy surfaces luminous in the moonlight. The eerie airborne structures resembled enormous white galleons arriving from another planet.

Besides Edward, the other steady inhabitant of Guantanamero Bay was Willow, an art major at Irvine. She and Edward were housemates, rather than boyfriend-girlfriend. Beach houses were more expensive to rent than the cottages I and the other students obtained in Laguna or back up the highway on the Balboa Peninsula or Balboa Island, or apartments in Costa Mesa. Edward required additional residents like Willow to defray costs. She was everyone’s image of a surfer girl: thin, fit, long blond hair, and out on the water with her board every chance she got. Whether she was in her bikini around the house, or in her wetsuit climbing down the path to Shaw’s Cove beach, she was heart-stopping lovely. Her breasts weren’t particularly large, but she was perfectly proportioned and moved with such grace she could have been a delicate onshore wind. She was always pleasant to talk to, interested in what was happening with you. Edward said she could be moody to live with, but I never knew when he was being contrary or when he was accurate.

As with Janey, Willow was a delight merely to stare at. When she swayed across the living room in the afternoon South Coast light, with the sound of the surf rising from the beach through an open window while birds twittered from the oleanders and fan palms, the air scented with pungent eucalyptus and perhaps a sandalwood incense stick burning in the room, this feast for the senses brought to mind the opening guitar chords of the Lovin’ Spoonful’s “Coconut Grove.” The song’s tune and lyrics proceeded as languorously but inexorably as Willow’s locomotion, or as combers curling onto sand:

Don’t bar the door. There’s no one comin’.

The ocean’s roar will dull the drummin’

Of any city thoughts or city ways.

The ocean’s breezes cool my mind,

The salty days are hers and mine

Just to do with what we want to.

Tonight we’ll find a dune that’s ours

And softly she will speak the stars

Until sun-up.

It’s all from havin’ some one knowin’

Just which way your head is blowin’,

Who’s always warm like in the morning

In Coconut Grove.

Willow had a boyfriend, Phil, who lived up in Venice. They’d visit back and forth. I’d met Phil a couple of times at Guantanamero Bay: he was a surfer, too, and seemed a nice guy, though I had never ascertained if he was interested in anything much beyond the location of the best reef or shore break, or what had occurred the last time he shot the pier at Huntington. He was tanned almost mahogany, and even his muscles had muscles. Phil was a ringer for the “after” panel in Charles Atlas’s “before” and “after” bodybuilding advertising — the photo slightly retouched with blond hair slicked back wet from a day’s surfing, a Hawaiian shirt like Edward’s, and a trim moustache. I never saw Phil at our parties.

Willow, too, was usually absent from those events. Edward said she didn’t care for parties much and decamped to Venice when we had one scheduled for the Bay. As always, I didn’t necessarily believe Edward: maybe she simply didn’t like our parties. I was never clear how she and Edward had ended up sharing a place. Had he met her through his art classes, if indeed he really was studying fine arts? Or did he know her from Hawaii? Once she had spoken about her parents living on the big island, so maybe that was somehow the connection with Edward, if indeed he really had operated a gallery in Hawaii. Being in art, she also knew Meg, Remi’s girlfriend, so there could have been a link there.

Not that it mattered; Willow was part of the ambience of the Bay, as were a couple of male housemates. The latter were acquaintances of Edward’s, although never Irvine students. During the past year, these individuals had shared the rent for a few months, then disappeared. Later you encountered their replacements drinking beer on the porch and were introduced. When you inquired after the former inhabitants, Edward was vague about their whereabouts.

The one cryptic letter from Edward I’d received during the summer said that Phil was temporarily living at the Bay since he’d been hired by a roofing company in Costa Mesa. I was curious, as I rounded the corner onto Cliff Drive, if Phil would still be there, or if he and Willow had maybe gotten a place together closer to his work up in Newport or Costa Mesa itself.

Edward’s TR was parked at the curb in front of the Bay. A Ford Econoline van and a Chevy four-door sedan rested on the short paved drive leading to the garage. I didn’t recognize the other vehicles; the van had a FTA bumper sticker. The initials, I knew, stood for “Fuck the Army.” There was no sign of Willow’s microbus, but perhaps she’d traded it in for the van. The Chevy wouldn’t work for her without roof racks to carry boards.

A light was on in the living room, and Edward answered my knock on the door. “Wayman,” he said, his face brightening when he saw me. “You’re back.” His brown hair was impeccably cut as usual, and he wore crisply pressed shorts and a red Hawaiian shirt decorated across the midsection with a broad brand of white flowers. Draped around his neck was a thin band of beads.

We shook hands. After three days on the road, I was glad to talk to somebody familiar.

Edward led me toward the kitchen. “Grab a beer. Now you’re with us again, the Revolution can begin.”

That was his kind of humour: a teeny bit of the needle, but good-hearted, really, underneath.

“How did your summer —?” I began, but stopped. Two young guys I’d never seen before were absorbed in concocting something in a boiling saucepan on the stove.

“I’d like to present my younger brother, Jay. This is his friend, Pump.”

The two swivelled around and regarded me. Both had moustaches and wore T-shirts and gaudily patched bellbottom jeans. The shorter of the pair, Edward’s brother, had a ponytail, and a beaded necklace similar to his sibling’s.

“Wayman here has just driven down from Canada,” Edward announced.

“Far-out,” Jay observed.

“Glad to meet you, man,” Pump said.

The three of us shook hands. “I didn’t even know Edward had a brother,” I admitted to Jay. My host was extracting a couple of Olympia beers from the refrigerator. I was pleased to see the bottles of Oly; everybody had been low on money by term’s end, and we had been reduced to drinking Brew 104 — an inexpensive L.A. brand reputed to be the result of 104 different attempts to brew beer properly, after which the company conceded defeat and marketed the horrible product regardless.

Edward was lifting down two plastic glasses from a cupboard over the sink. “Jay isn’t really his name. But the handle is apt. These two got out of the army about a month ago and they’ve been stoned ever since.”

“We’re making up for lost time, man,” Pump said.

“Not that we didn’t get ripped a few times when we were in,” Jay observed.

Pump giggled. “Yeah, right. A few times.”

“There’s been some outasight Colombian boo around,” Jay said. “Do they smoke grass up in Canada?”

I accepted a full glass from Edward, nodded, licked the overflow from one side, and took a sip. “Were you guys in Nam?”

“They never made it out of the Land of the Free,” Edward said.

“We were in electronics,” Jay explained. Pump had turned to check on the steaming utensil on the burner.

“The last eight months we were stationed in California,” Jay continued. “When we got our discharge, the natural thing seemed to be to hang out at Eddie’s for a while.”

“You mean the easiest thing,” Edward said.

Pump had swung around toward us again. “Till we figure out what we want to do.”

Edward held up his glass in my direction. “Besides getting stoned, he means. Anyhow, Wayman, welcome back to the Gold Coast, to the California madness.”

We clinked glasses. “Do you have other brothers and sisters?” I asked.

Edward twisted his face into a mock grimace. “One’s enough. Who knows what friends any others might bring by?”

The young guys giggled.

“How did you get the name Pump?” I asked.

“Some army deal,” Edward said, dismissing the question before Pump could reply. “Let’s you and I remove ourselves to the porch. You know what these idiots are doing?”

“Cooking?”

Edward shook his head, as if saddened. “They read in the Barb or the Free Press or Rolling Stone you can get off by boiling the meth out of the top of a nasal decongestant spray bottle.”

“Sounds like mellow yellow,” I said. A year earlier the rumour had gone around, apparently based on the lyrics of a Donovan song, that smoking dried banana skins would prove hallucinogenic. Despite valiant attempts by thousands of freaks in hundreds of kitchens, nobody got high.

“I think the caterpillar has eaten huge holes in their brains,” Edward declared. “I told them the best stone known comes from brick walls. You find a brick wall, lower your head, and run at it several times. It’s a fantastic trip — knock you right out. Really gets you wasted.”

He scooped two more Olys from the fridge and led the way among the elderly stuffed chairs and sofa of the living room through the open French doors onto the porch. I paused at the railing for a moment to reacquaint myself with the vista while Edward stretched himself out on a deck chair.

The tide was full. In the thickening light, the swells reared and crashed onto sand, then foamed up the beach. A few sandpipers, the last of the day, hunted for sustenance at the edge of the surf ’s frothy residue as each sweep of onrushing sea withdrew toward the Pacific. The air was a little misty with windblown spray. Above the regular cannonade of the surf, I heard the seals’ raucous sounds from the rocks offshore of the cove’s northernmost promontory. To the south along the curving coastline, the lights of the town flicked on behind Main Beach and up into the hills beyond.

“This makes driving two thousand miles worth it,” I said.

Edward was watching me dig the night. “You really like California, don’t you?”

“Who wouldn’t?” I hauled up a rickety wooden folding chair and sat beside him. Under the influence of the beach scene and the beer, I felt the tension of three days on the road start to leave my body. “Being here in California is like a trip to the future for me. This place might be crazy. But what I see here will make its way to the Frozen North in a couple of years.”

“You mean, eventually Canadians will be boiling up Vicks VapoRub?”

“Probably.” I told Edward about being offered a joint at sixty-five miles per hour approaching Tejon Pass.

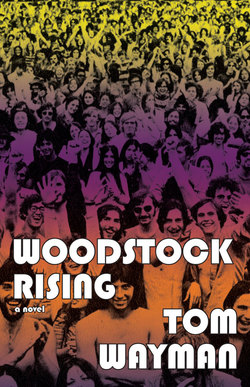

He laughed. “Did you hear up in Canada about the Woodstock Festival?”

Working my second-last-for-the-summer Tuesday at the Sun, I’d seen spiked on the wire desk a number of photos of the enormous crowds jammed onto Max Yasgur’s dairy farm in upstate New York. What had impressed me, as I related to Edward, had been the sense that for once we longhairs, peaceniks, appeared not to be a tiny minority of the population. For the first time we looked like a significant group, a power growing fast, a force that would have to be reckoned with.

“There were even some pictures of guys with long hair wearing hard hats and driving bulldozers, preparing the site,” I said. “I’d never seen freaks working construction.”

“You know, I had a chance to be there and turned it down.”

“What?” I wasn’t sure if this was one of Edward’s “stories.” I hadn’t ever known him to lie, exactly. He frequently produced tales, however, of previous encounters with famous men and women from the art, literary, or political worlds, stories we had no means of verifying.

Edward explained he’d been over at Bridget’s, a friend of ours from Irvine who had a house near the south end of town where we hung out sometimes. I knew vaguely that her boyfriend, who was the father of the child she was expecting when I left in June, worked at concert promotion in the Bay Area. Edward told me Don’s company wanted him to be present at Woodstock and had given him two tickets. Bridget this late in her pregnancy couldn’t fly. Don had been home in Laguna the night Edward had dropped by, and late in the evening after he and Don had gotten suitably loose, Don asked if Edward was interested in attending this big rock festival in the East. Edward had decided the New York deal sounded too flaky to be worth quitting his summer job early to attend.

“Bummer,” I said. “Hey,” I added, suddenly feeling guilty for not asking sooner, “did Bridget’s baby get born all right?”

“A boy. Both mother and child doing well. Jacaranda Eldridge Buzz O’Conner. We should go see them.”

“Eldridge, as in Cleaver?”

Edward nodded. “A flower, a Black Panther in exile, and ‘Buzz,’ as in Buzz Aldrin, the astronaut. Did they cover the moon landing in Canada?”

“It was quite a summer. I was at the SDS convention in Chicago in June. Then Apollo 11 landed in July, and the Woodstock Festival blew everyone’s mind in August.”

We pondered this list for a few moments. The seals had become silent, leaving only the recurring thunder of the surf.

I asked Edward how he had liked his summer employment. He had been hired by Laguna’s Chamber of Commerce to help with publicity, mainly promoting Laguna’s Pageant of the Masters. This was a bizarre, long-standing theatrical extravaganza whereby townspeople appeared onstage in Laguna Canyon, forming a tableau that reproduced as nearly as possible some famous painting. Each year the work of several Old Masters and the occasional modern art piece were rehearsed and presented. Why anybody would want to view a group of people pretending to be a painting was beyond me. Yet the pageant was an important tourist draw, injecting hundreds of thousands of dollars into the town’s economy. Undoubtedly, Edward had secured this job on the strength of the art gallery experience he either had, or hadn’t had, in Hawaii.

I was in the midst of a futile attempt to extract concrete information about Edward’s day-to-day duties for the pageant, when his brother and his brother’s friend emerged from the living room onto the porch. As they pulled up chairs, Jay revealed that their chemical experiment had been a failure. He and Pump endured with good grace Edward’s mockery of their earlier optimism. Jay produced an example of his namesake, claiming it was Mexican in origin, though unfortunately not the celebrated Acapulco Gold. We settled into some diligent toking.

The smoke I inhaled was landing in my brain after eleven hot hours on the road, not to mention a beer and a half. I felt almost immediately a humming exhilaration pervade my consciousness. En route to the porch, the boys had put a record on the stereo I recognized, an album Willow had frequently played last spring when I was over — a band called H.P. Lovecraft, named after the horror author. Their music, though, was laid-back, with intricate vocal harmonies that impressed me. My attempt to learn more about Edward’s summer employment floated away while he and his brother and Pump discussed household matters. Despite my mind having become sugarcoated, I managed eventually to insert an inquiry concerning Willow’s whereabouts.

“She’s living here, man,” Pump told me. “She’s re-upped for another year at you guys’ school.”

“Phil and her are up to Garden Grove to see his mom,” added Jay. “They’ll be back tonight.”

A master plan sprang into my pleasantly ruined brain. I had some idea that the Willow-Meg-Janey link might yield news that could prevent me making a fool of myself by trying to reconnect with Janey. No point in asking her out again if, for instance, she had become hot and heavy with somebody over the past two months. I was too shy to raise the subject with Edward. But if Willow showed up later, I could casually broach the topic. Even then the inquiry would have to be phrased delicately. On the turntable, H.P. Lovecraft were uttering a melodious complaint about a girlfriend’s betrayal. Behind the words, two electric guitars spoke back and forth. Except when the loss being articulated by the lyrics became too painful, an organ and some mellifluous scat wove to and fro under the song’s sad tale. A background chorus, “Shawn — shawna-wanna-way-o,” was repeated soothingly. Yet resentment was decidedly being voiced in the forefront:

How could you

Be so cool

To sit and let me

Play the fool

And pick up all the tabs

For all your fu-un?

I bought your

Brand-new clothes

And heaven only knows

That all the time

I thought that I was

Number one.

Well, I saw Fred yesterday.

He says he saw you in L.A.

Well, I hope the weather’s groovy

Way out west.

If that’s how much you love me, baby,

More or less.

I tripped out on the song, cautioning myself to be ready to learn — if not tonight, then sometime in the next few days — that Janey had indeed found somebody else over the summer. Not someone else, I corrected myself: she and I didn’t really have anything going.

From a distance I heard Edward’s voice stating that he had run into one of my SDS colleagues, or should he say, comrades, the day before yesterday downtown on Forest. He had been told that the SDS convention had been wild. The bubble that had been slowly expanding within my mind unexpectedly popped, and I perceived I was both deliciously and thoroughly stoned and at the same time possessed an augmented capacity to be articulate, to communicate a penetrating and convincing utterance on any topic.

“Who did you talk to?” I succeeded in asking.

“Emma.”

Emma was a main energy source for UC Irvine’s SDS chapter. A Ph.D. student in anthropology, tall and gangly and about my age, she was already immersed in the organization when I started attending the occasional meeting my first September at Irvine. During the initial couple of months, I regarded her as far too involved in protest politics. On my first visit to her ground-level apartment a few blocks toward Boat Canyon from my house, I was amazed by her rooms filled with stacks of pamphlets and radical newspapers, and bookshelves bearing volumes by Marx, Lenin, Mao, Fanon, Marcuse, and similar left-wing heavies. The only decoration on her walls were posters that declaimed what I then considered embarrassing slogans about imperialism and the working class, or heroic images of Cuban and Chinese revolutionaries. Emma had arrived at Irvine from Cornell the year before when UCI — one of three new campuses in the Cal system — had opened. On the rear window of her microbus, mimicking the Greek letter car window decals that identified the fraternity or sorority of a vehicle’s owner, Emma had affixed a sigma, delta, and sigma. Irvine didn’t even have any frats yet, though I’d seen such Greek letters displayed during my undergrad years at the University of British Columbia.

“You’re in SDS?” Jay asked.

“What’s SDS?” Pump inquired, offering me another hit from the doobie.

“Students for a Democratic Society,” I said before sucking in the sweet smoke.

“Commie scum,” Edward contributed helpfully. We all laughed.

Pump was focused on relighting the joint Edward had returned to him. “Are you one of those campus protesters, man?”

I tried to concentrate how best to present myself to a stoner fresh out of the army. “Even before I heard of SDS … I thought the war was wrong.” I explained that after the Vietnamese kicked out the French, Eisenhower promised free elections. “Ho Chi Minh would have won hands down, so the U.S. made damn sure that vote was never —”

Jay stood. “I’m going to change the record.”

I realized H.P. Lovecraft had finished.

“You can see why Wayman is a clear and present danger to the republic,” Edward said to Pump.

“No, no …” I demurred. Even to myself, I had sounded incoherent about why I belonged to SDS. Being ripped out my gourd wasn’t helping. From inside the house, familiar opening chords announced Jefferson Airplane’s “Come Up the Years.”

“The civil-rights movement got me thinking, too.” I launched into a rap I’d delivered before to students who browsed our weekly SDS literature table on campus and initiated a conversation. How could America, I would ask them, with all its inspiring statements about freedom and dignity in its founding documents, still have water fountains marked FOR COLORED ONLY a hundred years after the Civil War supposedly ended slavery? Or civil-rights activists being shot for helping black people register to vote? “How can such contradictions —”

“Good choice, man,” Pump called, startling me. I understood a second later his comment was aimed at Jay’s musical preference. Pump must have caught my surprised expression, because he gestured toward me. “Sorry.”

“When I got to Irvine,” I continued, still attempting to sort out what I should tell him, “the SDS chapter showed me how things like the war and racism and the university tie together. How school teaches us to shut up, obey, put up with boredom, serve the corporations and the status quo. Whatever’s going on, it’s not about a real education.”

Jay had re-entered the porch during my little rant and accepted the joint passed to him by Edward. “‘Something is happening,’” Jay quoted Dylan’s “Ballad of a Thin Man.” He took a drag and continued between his teeth: “‘But you don’t know what it is, do you, Mr. Jones?’”

“That’s about it,” I confirmed. I was feeling a little sheepish about rapping on and on. “How did you guys wind up in the army? Were you drafted?”

“Did you and Pump finish the taco chips?” Edward asked his brother.

“In the cupboard, below the toaster,” Jay said. “Last time I looked.”

Edward hoisted himself from the deck chair and disappeared into the house. From the living room the Airplane were admonishing us, in a tone of exaltation, to heed the brevity of existence:

Some will come,

And some will go.

We shall surely pass

When the wind that

Left us here

Returns for us at last.

We are but a moment’s sunlight

Fading in the grass.

C’mon, people, now,

Smile on your brother,

Let me see you get together,

Love one another

Right now.

“Fool that I was, man,” Pump said. “I enlisted. I’d finished high school, didn’t know what to do. I was 1-A, anyway. They promised you had more choice if you went in voluntarily.”

“Dummy,” Jay said.

“You did the same,” Pump complained.

“You enlisted out of high school?” I asked Jay.

“I wasn’t a brain like Eddie. I’d just broken up with a girlfriend. Seemed like a good idea at the time.”

“We were lucky, man,” Pump said. “Plenty of suckers like us wound up grunts in Nam. So much for learning a trade.”

“The army was an education,” Jay said.

“Yeah, you learn what not to do with your life.”

“We’re catching up on what we missed, though, since we got out,” Jay added.

“Not that we didn’t get blasted inside, too,” Pump chortled.

Edward emerged through the doorway carrying a large bowl of corn chips in one hand and a smaller bowl of salsa in the other. With his foot he hooked a small stool out of a corner of the porch and lowered the bowls onto it. “Whatever Wayman’s been telling you, don’t forget he’s not even a citizen.” Edward reclaimed his deck chair. “His road to ruin should be a lesson for you boys.”

“Ruin?” Jay asked.

“We’ll need more beer to wash these down,” Pump observed.

Edward reached for some chips. “Go get them then.”

I picked out some chips myself and ran them through the salsa.

“You mean ruin, as in how he became a protester?” Pump coughed, and smoke streamed out his nose.

“A radical,” Edward said.

“I didn’t start out radical,” I objected, chowing down on the chips.

I considered mentioning how maybe journalism was the starting point for me coming to hold the beliefs I did. First as a reporter for the UBC student newspaper, and later on the Sun, I had been shocked when I interviewed authorities concerning injustices or other societal failures. This response was reinforced when I listened to Sun reporters tell their insider’s experiences with politicians and bureaucrats. Whether the issue was substandard student housing — converted old army barracks still in use, with rotting floors and leaky plumbing — or repressive university policies, or provincial government or corporate scandals, the men and women in charge appeared incapable of mustering a convincing argument to defend their decisions, actions, or inaction. I had grown up expecting the world to be orderly, rational, with any remaining social problems on the verge of solution. The reality I discovered was very different.

“When I first got involved with SDS, they were into an activity called Gentle Thursday,” I told Pump. The idea, I explained, was to reveal that the university is repressive, despite its tolerant appearance. On Gentle Thursdays people were supposed to come to campus and be gentle — bring babies and balloons, fly kites, blow bubbles, play guitars and flutes, romp on the grass, get high and trip out.

“Sounds like a be-in,” Pump said.

“Where’s that beer?” Edward demanded.

“Exactly,” I said. “The deal was, the university would crack down on all that, saying, ‘You can’t be gentle here.’ That would prove its true nature.”

“Doesn’t seem very radical,” Jay said.

“That’s my point. Three years ago, that’s the sort of activity —”

“You hapless hippies might have thought you were being provocative,” Edward said. “The administration treated it like any wacky campus event. It might as well have been a Homecoming Week stunt — if Irvine had been around long enough to have a Homecoming Week. Frat boys cramming into a phone booth.”

“Definitely,” I said. “But SDS kept changing. Gentle Thursday didn’t last long as a protest. We thought more about everything, read more, rapped about it, pushed back harder at what was pushing us around. I don’t necessarily mean at Irvine. All across the country.” I launched into how I had originally regarded Vietnam, segregation, the way the university functions as just aberrations. But slowly I became convinced these were direct consequences of how North American society is structured.

“You take heed,” Edward mock-cautioned his brother. “Listen to Wayman’s subversive talk, and who knows where it will lead.”

“It’s about changes, that’s all,” I said, trying to sum up, starting to wish there were refills for the beer.

Edward chuckled, his mouth full. “Give the university some credit for tackling racism. Remember the Watts project?”

“What about Watts?” Jay asked.

“That’s pretty funny,” Pump interjected, tittering. “Watt about whats, you mean.”

“Watts blew out in August,” Edward said, ignoring Pump. “Irvine first opened its doors that September.” He turned to Pump. “Are you going to get those beers or not?”

Pump stood, grabbed a handful of chips, and moved indoors.

“Some bright light had the idea that Orange County kids needed to be sensitized to racism.”

“When was this?” Jay asked.

“Sixty-five. I came the following September. Same as Wayman. But everybody was still talking about it.”

Pump was back with four bottles. “These are the last,” he announced. All four of us munched with dedication.

“How did Watts figure in?” Jay prompted.

Edward related how in the interests of interracial harmony UCI sociology students were bussed to Watts once a week to learn about the black experience. “The organizers put them in a room and let some beautiful black brothers and sisters harangue them about what racist pigs white people are. Very morally uplifting.”

“Doesn’t sound too cool, man,” Pump said.

“This went on week after week,” Edward continued. “Finally, one time this soul brother is berating the Irvine contingent for being gutless, like every whitey. ‘We burned down motherfucking Watts,’ he says. ‘You chicken-shit honkies would never be able to do anything like that.’ One of the UCI students seated by a window calmly pulls out his lighter and sets the curtains on fire.”

Jay hooted. “Right fucking on.”

“Too much,” Pump said.

Edward smiled. “The place starts to go up in flames. Everybody freaked. That was the end of the program.”

“To be fair,” I said, “I learned something about racism from a guy from Watts. He spoke on campus that first September we were here. I can’t remember his name, but he had a big Afro and wore a fifty-calibre machine gun bullet on a chain around his neck.”

“That’s heavy,” Jay said.

The speaker, I recounted, had helped organize patrols in Watts that would dog the cops when they rousted people. The patrol would cruise the streets, and whenever they saw a cop hassling somebody, or making a bust, they’d pull over and act as witnesses.

“I’ve heard about that,” Pump said. “Black Panthers.”

“These guys weren’t Panthers, just community activists,” I said. “I was impressed by their jam, though. The cops weren’t too thrilled about having a bunch of blacks tailing them. The guy said he had about a thousand and one tickets for every form of vehicle and traffic violation. He said the LAPD once had him face down across the hood of his car. A cop rams his gun against the side of the guy’s head and says, ‘Nigger. You are one second from eternity.’”

“I wouldn’t like that, man” Pump said. “Were these the last of the taco chips?”

“Go up to the liquor store and get some more,” Edward ordered. “Pick up some Olys while you’re at it.”

“Who was your servant last year?”

“How much good do you think bird-dogging the cops did?” Jay asked.

I shrugged. “Who knows? Like Pump said, the Panthers began patrols in Oakland after that, or maybe at the same time.”

“I bought the last dozen beers,” Pump said.

“It didn’t stop Watts from burning again a year ago when King was shot,” Edward said, ignoring Pump.

“Not to mention a few other cities,” I added.

“I’ve never understood why they’d torch their own neighbourhoods,” Jay said.

This was a comment I’d encountered at our SDS literature table when somebody was upset by the black liberation material we displayed. “Maybe they don’t feel it is their neighbourhood,” I suggested. “They don’t own it or control it.”

Jay looked dubious.

“I’m pretty sure Jay and I bought the beer before that, too,” Pump weighed in.

“Nothing I’ve read or heard indicates the ghettos have improved any since 1965,” I said.

“They keep burning it down,” Jay insisted.

“It’s your turn, Eddie,” Pump concluded.

“Forget it! Whose house is this?”

Pump was scouring the last of the salsa out of the bowl with a chip. “You ever get into any far-out action, man?” he asked me.

“Nothing like Watts.”

“Wasn’t some protester killed by the cops in Berkeley this spring?” Jay asked.

“When the cops cleared People’s Park in May,” I confirmed. “I’ve never been in anything like that, either. The worst for me was Century City. That was scary enough.”

“Where?”

“In L.A. a couple of years ago.”

“Are you going to roll another?” Edward asked Jay.

“Huh? Oh. Sure. Just a sec.” Jay moved toward the door.

“Nobody got offed?” Pump asked.

Jay was back from the living room with a baggie and papers. “What about Century City?”

I thought I better put the experience in context. I told how a contingent from UCI had driven up to San Francisco for the big peace march that April, the first anti-war mobilization to be called in New York and San Francisco simultaneously. Two years ago, I reminded Pump and Jay, was supposed to be the Summer of Love: peace, flowers, good vibes.

“‘If you’re going to San Francisco, be sure to wear some flowers in your hair,’” Edward sang, his tone mocking.

“I thought you said Century City was in L.A.,” Pump objected.

“I’m coming to that,” I continued. “Fifty thousand people were at the San Francisco march. I’d never seen close to that many human beings at one demonstration. Marchers were handing flowers and balloons to the motorcycle cops, and they’d attach them to their bikes. Everything was groovy. It was all — ‘What do we want?’ ‘Peace.’ ‘When do we want it?’ ‘Now.’ Not too much of — ‘Hey, hey, LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?’ Our crew had travelled up in a couple of cars. We were a real mix — SDS and just students opposed to the war. We didn’t have signs of our own, so we marched behind the Orange County Peace Center banner. The idea of there being a Peace Center in Orange County drew a huge laugh and a round of applause whenever people first caught sight of our banner.”

“How come?” Pump asked.

“Orange County’s regarded as very right wing,” Edward explained. “Why do you think John Wayne lives in Newport?”

“He’s sick of cows?”

The Century City protest was two months later, in June, I went on. Johnson was visiting L.A., staying at the Century Plaza Hotel, where he was going to speak at a thousand-dollar-a-plate fundraising dinner. A coalition of local peace groups called a demonstration. We figured it would be another version of the San Francisco march.

“L.A. isn’t the Bay Area,” Edward interjected.

The march organizers knew that, I agreed, so they expected a small turnout. But ten thousand people showed up, probably because we were going to protest in front of LBJ himself. The organizers were totally unprepared for so many.

“What kind of preparations does a march take, man?” Pump asked. “Don’t you just start walking?”

Edward snorted. “You’re not parading down the sidewalk.”

“Oh. Yeah,” Pump giggled.

I explained how you have to assemble someplace beforehand and arrange for speakers where you’re going to finish up. Traffic needs to be rerouted, which involves permits and the cops. Your own marshals are needed to keep things moving, or hold the march up at certain intersections. And to ensure things are as cool as possible with the Man or with hostile spectators.

“Don’t bogart that, Pump,” Jay said.

Pump handed him the remnants of the doobie. Jay affixed his roach clip to it, one of the more elaborate ones I’d seen. The pinchers were soldered to a wire rising out of an elongated diamond of stained glass. Three leather cords, each with a coloured bead near the end, were tied to the wire below the pinchers. The smouldering weed went around another time. I declined a toke, wanting to retain what clarity my brain still possessed to relate events.

“When we arrived at the assembly area, we could tell right away this wasn’t going to be anything like San Francisco,” I continued. “The LAPD motorcycle goons were zooming up and down, trying to ride herd on us. Seeing how close they could come to us without driving right over our feet. If anybody offered them a flower, they just threw it onto the ground. They would have stomped on it except that would have meant climbing off their bikes.”

My remembrances were still vivid. At the assembly point people filled the whole street for what looked like miles. The march was supposed to begin around 6:00 p.m., but we waited for more than an hour before we started to walk. By now the sun was beginning to set.

Those of us from UCI were about a quarter of the distance back from the front of the march when at last we heaved into motion. In the shifting, fluid alignment of people in a procession, I ended up mostly chatting with a fourth-year Spanish major, Henry, who had frequently attended our SDS meetings but seldom said much. Occasionally, Emma, in whose van I had ridden up to L.A., or another Irvine student I knew drifted up alongside as we plodded forward. Unlike at San Francisco in April, this march was far from boisterous. Participants seemed solemn, even a bit tense, as the LAPD motorcycles raced back and forth along the march perimeter, jarring me with the sudden gunning of their engines. Despite the cops’ constant patrolling, chants as usual originated from someplace ahead or behind, swelled, and died away.

As our part of the protest came opposite the hotel, the parade ground to a halt. The pause went on and on, much longer than a delay to allow a traffic light to change. People speculated to their neighbours about the reason for our lack of progress. Somebody announced he had heard that the cops had blocked the march. A couple of freaks from our vicinity departed to check out what was happening. The duo showed up after about a quarter of an hour to report that a group at the head of the march appeared to have launched a sit-in on the road.

Meanwhile, the light was getting dimmer. Police choppers circled low overhead, engines so loud I could hardly hear Henry or anybody speak beside me. Street lamps switched on. The high-rise hotel where LBJ was staying was set back from the road where we stood. Lights began to appear in the windows. We did some half-hearted chanting: “One, two, three, four, we don’t want your rotten war.” Everybody was patiently waiting for the march to resume.

By accident I had been walking on the outside edge at the time we stopped, so I had a clear view west across the hotel grounds. All at once several squads of police jogged toward us from that direction. The cops seemed to individually swell in size as they advanced. In seconds they formed up shoulder to shoulder along the curb, creating a barrier between our stalled parade and the hotel. Everyone, of course, turned to face them. The moment the march rotated toward the cops I was on the front line.

Opposite me, eyeball to eyeball, was a guy in a helmet. He was maybe six or eight inches taller than I, but his bulky gear made him loom even larger. His club was drawn and angled across his chest so that the business end of the stick rested in his open left palm. He was wearing black gloves. But his club didn’t frighten me as much as his eyes. He looked scared. He was a big guy, and he was spooked.

The thought struck me: He imagines there are thousands and thousands of us united against just him. He doesn’t realize we’re actually a ragtag and bobtail lot with not much in common except a desire to protest the war. I also had a flash that being in a situation where somebody armed and dangerous was scared of you probably wasn’t a good idea.

I was aware of nervous chatter in the crowd as everybody around me became more and more uptight. Me, too. Not that I could hear anyone very well, since the choppers constantly thrashed by above us in the dusk, or hovered, red and white lights blinking. I was getting more anxious by the minute. A middle-aged woman a few people over to my left was trying to talk to the cop in front of her. He displayed no evidence he was aware of her existence. Indeed, the row of helmets and clubs we faced were all impassive, except their eyes occasionally darted from side to side. I heard yells and screeches in the distance to my right becoming louder. A disturbance, sort of a pandemonium, rolled closer and closer down the line.

A single cop pushed through the wall of uniforms opposite us from behind the others. The ones he jostled aside looked startled. The intruder had sergeant’s stripes, and his face was a mask of rage. The world became very slow. I heard the sergeant yell, “Move back, you sons of bitches. Move back.” He had his club pointing forward, cradled in his left hand, and with the heel of his right palm he drove — with what appeared to be every ounce of his strength — the end of the club into the pit of the stomach of the man immediately on my right.

The guy who was hit groaned and collapsed across me, gasping for breath. The sergeant was gone; everybody around me was screaming. I heard a thwack and yelling a few people to my left. I guessed the sergeant was darting through his men all down the row, trying to get us to disperse.

By now everything was nuts — shrieks, curses, sirens, the roar of the choppers. Those of us directly confronting the helmets and clubs instinctively took a step or two back. A couple of marchers tried to assist my injured neighbour as the crowd behind pushed at us, shouting, “Stop! We’ve got no place to go!” I started to panic, feeling trapped between the line of police and my fellow demonstrators.

Then either our motion backward inspired the cops, or they obeyed some bellowed command that didn’t register with me. They surged ahead, clubs swinging.

The next fifteen minutes were a blur. The crowd to the rear sized up the situation the instant the cops charged — everybody scrambled. The cacophony was ear-splitting, and I was freaked. I ran, along with the rest of the demonstration. As I pounded on, I tried to keep Emma and the other Irvine students in sight so I wouldn’t get separated from them among strangers. At the edge of a freeway, people in front of me were already sliding down the embankment and out onto the asphalt. Traffic had jammed to a halt, horns blaring, adding to the racket. Protesters dashed between the idling, honking cars. Then I was down the bank, through the traffic, and up the other side. I climbed over a wire fence with a bunch of other people into a completely unfamiliar neighbourhood.

“You never got popped?” I heard Jay ask. I had let the account of my escape trail off.

We listened to the surf for a moment.

“No,” I finally said, pulling myself together. “I had a vague idea which direction we had left the car, and somehow we all rendezvoused there. But next day, the Times reported two hundred and fifty demonstrators injured and fifty busted. The pigs really whaled on people.”

“Far-out, man!” Pump declared.

“The Free Press had a giant headline calling what happened to us a police riot,” I said. “Before Century City I thought only ordinary people could riot, and the cops restored order. It never dawned on me the pigs could riot.”

“That didn’t stop you protesting?” Jay asked.

“No. We still have to end the war. I don’t intend to get busted, though, if I can help it.”

“Makes sense,” Pump agreed.

“I have to tell you,” I confessed, “I’m a practising coward. I’m convinced our society needs fundamental change. That we have to protest and take whatever steps are required to struggle for a more just, more equitable way of organizing society. That said, I like to stay out of trouble if I can. I’m not someone who believes that having more and more people arrested will influence the government to change its mind. I’m sure the government will happily build more jails if necessary.”

Edward laughed. “No doubt about it.”

“I like the idea of doing something to screw the system,” Jay said. “But I don’t know if I’d willingly go to jail.”

Pump grinned. “Yeah, we’ve been in the army, man.”

I assured Jay there would be protests during the fall he could take part in. As I spoke, I was conscious of my arms and legs feeling weighted and sluggish, whether due to reliving my terror at Century City, or ingesting too much smoke, or because my days on the road were finally catching up to me. I drained the last of my beer and thought of something that might intrigue Jay.

“One of our guys in SDS now, Thad, is a vet like you two. Did a tour in Nam. He decided last winter to ride the buses taking draftees from Santa Ana up to the L.A. Induction Center. That takes a lot of guts, as far as I’m concerned.” I explained how our SDS chapter helped Thad make up some leaflets on the war that also outlined alternatives to being drafted. “As the bus rolls up to L.A., he distributes the leaflets and raps to the guys about what the army is going to be like and about being in Nam.”

“They let him do that?” Pump wondered.

“He claims the trip’s paid for by the government, so he’s entitled to ride. The bus drivers don’t object, apparently, and he feels he wants to do it. He’s pretty fearless.”

“He’s in SDS?”

I shrugged. “He shows up at meetings. SDS is … you don’t have to formally be a member. Nobody cares whether you’ve joined or not, as much as whether you take part. I don’t even know if Thad’s a student. Emma’s always after people to officially sign up, because that way you get New Left Notes, the SDS paper. It offers quite a different view on what’s going down than you get from TV or the regular newspapers.”

“Who’s Emma?” Pump asked.

“Don’t let Wayman’s silver tongue convince you to become a Commie,” Edward said. “From what Emma told me about your convention, SDS might not be around much longer, anyhow.”

“She said that?” I asked, surprised.

“Not in so many words. But I inferred it. We didn’t talk long. I figured I’d get the gory details from you.”

My mind replayed images from inside the vast auditorium of the Chicago Coliseum. Day after scorching June day, the hundreds of delegates gave the impression of constant, restless motion. Tension was intense around each agenda item. From the stage, or in the aisles where mikes had been set up for long lines of delegates to express their views, impassioned speakers were incensed about matters that seemed far removed from the concerns of the Irvine students who assembled Wednesdays at 4:00 p.m. in room 204 on the second floor of the Commons Building. Even less familiar was the mass chanting that began to occur regularly after somebody finished speaking: hundreds of voices raised in unison to rehearse slogans intended to support — or to refute — a position that had just been expressed. The chanted catchphrases were accompanied by fists and Little Red Books — plastic-bound copies of Quotations from Chairman Mao — thrust rhythmically into the air at the end of a forest of arms. The shouted syllables clashed and echoed above among the structural trusses supporting the roof of the building.

“The first meeting of our chapter since the convention is next week,” I said. “I’m confident we’ll sort it out.”

“Even though you’re all crackpots,” Edward said.

“I don’t think we’re any odder as a group than grad students,” I countered. “Even if we were, paying attention to what’s really happening in the world would make anybody a little strange.”

“Maybe if you’re a little out of it to begin with, you pay extra attention to what’s going on around you,” Jay said.

I stared at him with new respect. “Right on!”

“But Emma said something about a split in SDS,” Edward insisted.

I explained how the gathering had voted to expel from SDS members of Progressive Labor, a small hardline Maoist party.

“The bad guys got booted then?” Jay asked.

“In short, yeah,” I confirmed. “We heard too many stories about how manipulative PL are, misleading people about what they’re up to, imposing an agenda that doesn’t reflect the wishes of the majority in a chapter.”

“You said they’re Maoist?” Jay pressed.

“You mean PL? Yes.”

“But you’re wearing a Mao button.”

I glanced down at my jacket, at the miniature profile of the portly Chairman’s head set in a red circular background in the centre of a small silver star. “Everybody’s a Maoist,” I tried to explain. I described how the National Office had led off the campaign against PL at the convention with a speaker who had been a Red Guard in China. How the honchos on both sides in their speeches referred to passages from Mao’s writings to bolster their arguments.

“Seems to me, man,” Pump said, “that’s like two people who disagree both quoting the Bible to prove their point.”

I had to acknowledge that Pump was right. Yet at Guantanamero Bay I didn’t elaborate on how disorienting I had found the outbursts of chanting in response to differing ideas. If PL’s supporters approved of a spokesman’s or spokeswoman’s statement, they intoned a singsong “Mao, Mao, Mao Tse-tung,” while waving aloft the Little Red Book. Our side was at a loss how to react at first, but quickly adopted a slogan from Che’s writing. Before he was killed he had said once that the goal for the progressive elements of a society shouldn’t be to sympathize with the plight of the Vietnamese, but to share their fate. What would defeat U.S. imperialism, according to him, was the creation of more armed movements to resist American military and financial support for local oligarchies, and other U.S. efforts to undermine democratization and national independence in Latin America, Africa, Asia. If we were in favour of an opinion, somebody onstage or at a floor mike proclaimed, we were supposed to rhythmically bellow from our seats Che’s call for “Two, three, many Vietnams,” while brandishing clenched fists to the beat. PL began to immediately counter any of our recitations with their own. Eventually, episodes of slogan-chanting and gestures, occurring alternately or even simultaneously, persisted after every speaker until people tired, or until the mindless activity had lasted long enough to appear ridiculous even to its most fervent practitioners. The ritual resembled a cross between a high-school pep rally and, I had thought, a TV news report showing some off-the-wall Third World political assembly.

I offered Pump an explanation I’d arrived at after pondering our convention behaviour for weeks. “Both sides quoting Chairman Chubby is weird. But people are looking for a model for change that works. Mao and the boys kicked out the foreigners who’d carved up China. The cycle of famine got stopped. Ordinary people at least have a chance now at education and other opportunities available to only a handful when most of the population was doomed to live as coolies.”

I assured Pump I wasn’t saying everything was perfect in China, or that all their ideas would work here. But, I stressed, Mao did conduct a successful revolution, one that looked impossible when he started. And he and his Communist Party had managed to modernize the country enormously in twenty years.

“Even started a space program,” Edward added.

“What?” Jay asked.

“Put up a satellite this summer. Couple of weeks before the moon landing.”

“You’re kidding.”

“I saw something about it on TV,” Pump said. “Doesn’t it just play a song?”

“‘The East is Red,’” I confirmed, recalling the news item.

Jay frowned. “Huh?”

“It does seem goofy,” I admitted.

“All that technology, effort, and money to fire a satellite into orbit,” Edward said. “The only thing the satellite does is broadcast a tape of somebody reading quotations from Mao, plus a recording of that song.”

“It broadcasts a song?” Jay asked.

“They’re demonstrating capability,” Edward declared. “If you have rockets that can orbit a satellite, obviously you have ICBMs or at least the potential to build them. The good old U.S.A. better watch out.”

“Maybe it’s to make them feel better,” Pump said.

We stared at him.

He shrugged. “National pride, man. The U.S. and Russia have satellites. Maybe the Red Chinese think that to earn respect you have to have one of your own.”

“I can dig it,” Jay said. “What was the use, really, of us putting a man on the moon? Except to show we could.”

“We even left the flag up there,” Edward said. “And, what’s worse, a plaque with Nixon’s name on it.”

Pump stood. “You’re right, man. The moon shot was definitely ‘Rah-rah, America.’ The same for your Mao guys.” He gestured toward the living room. “What do you want to hear?”

Jay snapped him a salute. “Something American.”

“Crosby, Stills and Nash?” Pump asked over his shoulder.

“Affirmative.”

I reviewed mentally what I had been saying about SDS and the convention. The stately toc-toc-toc drum pattern that established the rhythm of CS&N’s “Wooden Ships” was audible, followed by the decisive organ and guitar chords that kicked off the melody. “SDS isn’t really just a bunch of whacked-out Maoists,” I announced. “Once the term gets underway, everybody will be back to reality. After all, the New Left is not supposed to be ideologically rigid like the Old Left was. Everything happens so fast these days, it figures we’d start down the wrong road occasionally.”

Pump stepped out of the living room, carrying a candle and couple of dinner knives.

“At the convention I was reminded how rapid the changes have been. The Chicago cops were quite interested in our meeting, and that meant —”

“What a surprise,” Edward said.

“They had a TV camera in the window of a second-floor apartment across from the Coliseum entrance. You got filmed coming and going. The first afternoon an undercover cop posing as a delegate was discovered. I don’t know how he attracted notice, but somebody went through his wallet and it contained police ID.”

“Not too swift if he was supposed to be undercover,” Jay observed.

“I’ll say. After that, delegates were checked whenever they entered the hall. You had to turn out your pockets, be patted down, and have your wallet or purse searched. Each delegation in turn had to provide the inspection detail at the front doors. We called the security force ‘People’s Pigs.’”

Edward grinned. “You were a pig?”

I nodded. “Southern California region was on duty one noon hour. I was holding this kid’s wallet. The changes he’d been through had happened so quick he hadn’t even had time to clean the stages out of his billfold. He had his high-school student card, his draft card, his ID card from the McGovern campaign, a student card from U Wisconsin at Green Bay, something from a Milwaukee draft resistance group, and his SDS membership card.”

“He probably won’t stop there,” Edward declared. “So, Wayman, what’s next for him?”

“I know what’s next,” Pump announced from where he was squatting beside his arrangement of the candle, now lit, the knives, and a chunk of hash in a twist of plastic wrap.

“What?” Edward demanded.

Pump looked up at me. “The Beatles are right, man. People aren’t going to follow you if you’re carrying pictures of Chairman Mao. What’s next is Woodstock. You hear about Woodstock up in Canada? That’s what’s next — the Woodstock Nation.”