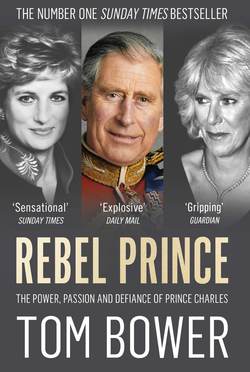

Читать книгу Rebel Prince: The Power, Passion and Defiance of Prince Charles – the explosive biography, as seen in the Daily Mail - Tom Bower - Страница 10

4 Uneasy Lies the Head

ОглавлениеAt 6 a.m. on Sunday, 31 August 1997, Higdon, calling from America, reached an acquaintance at Balmoral, where the royal family was staying.

‘What shall we do?’ he asked.

‘Nothing,’ came the reply. ‘Our worries are over.’

Elsewhere in the castle, Charles was chanting, ‘They’re all going to blame me, aren’t they? The world’s going to go completely mad.’

In the hours after Diana’s death, her former husband was paralysed by guilt. One of the queen’s courtiers would say that even his sons were critical of him for what had happened. Others would point to those same advisers and the royal family itself for encouraging the marriage, and then allowing it to veer out of control. No one had imagined that after a decade of crisis the royals’ plight could get so much worse.

Over the following days, the reports about Charles’s reactions were contradictory. His critics among the queen’s courtiers in Scotland recounted that he dithered about going to Paris until the queen said, ‘I think you should get out there.’ Others recalled that he insisted, against the queen’s wishes, on flying to France to bring back the body, until the monarch was silenced by Robin Janvrin’s question, ‘Would you rather, Ma’am, that she came back in a Harrods van?’ The majority of the media, relying on Bolland, who was at Balmoral, reported that Charles had taken control. They either concealed or were ignorant of his reluctance to fly to Paris. As the media’s only ‘eyewitness’ source, ‘Bolland could spin what he liked,’ one journalist griped.

There was no precedent for managing the death of a global icon who was no longer a member of the royal family but was nevertheless the mother of the future heir to the throne. The same courtiers who had mismanaged the announcement of Charles and Diana’s separation in 1992 struggled to decide whether the flag over Buckingham Palace should, contrary to tradition, be flown at half-mast for Diana’s death, and whether she should be buried privately or after a state funeral in Westminster Abbey.

That Sunday morning, none of those involved – Robert Fellowes, Robin Janvrin, Charles Anson and Stephen Lamport – could judge if Diana’s death was a tipping point for the monarchy. While the public’s perception of Diana could not be ignored, the four officials focused on protecting the queen. Any misstep would have embarrassed the monarchy, and perhaps even jeopardised it.

By the time Charles had accompanied Diana’s body back to London, the four advisers still underestimated the scale of the public’s distress. The prime minister’s description of Diana in his TV address as ‘the people’s princess’, compared with the queen’s seclusion in Balmoral, increased the nation’s dissatisfaction. As the outrage grew, the queen’s advisers searched forlornly for solutions. Unexpectedly, they found themselves relying on Tony Blair.

The prime minister had placed himself in an awkward position, as over the previous months he had built a rapport with Diana. Blair’s delusion about a special relationship, born of his desire to politicise the princess as New Labour, had irritated Charles, but he enjoyed receiving telephone calls during which she would comment on a photograph or one of his statements: according to him, they showed that ‘she had a complete sense of what we were trying to achieve’. Sympathetic to her challenge to the Windsors’ traditionalism, Blair was unconcerned that Diana gave the queen, as he wrote in his memoirs, ‘good cause to be worried’. Yet, in the days after Diana’s death, he and his Downing Street aides helped the family and their advisers overcome unfortunate obstacles.

Advised by Robert Fellowes, the queen did not adjust her principles. The monarchy, she knew, although buffeted by challenges, would survive if she focused on reaching the agreed destination, namely a funeral that satisfied the nation. By contrast, Charles’s inner circle was conflicted. Just when the public longed for him to lead by example, he was indecisive. ‘Why do you have to make everything a matter of principle?’ Fellowes had once exclaimed to a man who even in mourning considered the world was being unfair to him. To Charles, Fellowes and his family were especially intolerable. Fellowes’s wife, Jane Spencer, was Diana’s older sister. Diana’s eldest sister, Sarah McCorquodale, had been widely reported as Charles’s official girlfriend in the late 1970s, but her time as his accepted companion was terminated after an indiscreet remark she made to a journalist. The combination of those old antagonisms and Charles’s torrid relationship with Diana complicated Blair’s discussions with the queen and Fellowes.

It did not help that the prime minister did not fully understand the conflicts within the royal family. Speaking with limited deference, he saw his duty as ‘to protect the monarchy’ from the public’s rage. The courtiers’ initial gratitude turned into suspicion. Blair did not understand that governments do not own the monarchy. Thirteen years later, he admitted that he had presumptuously lectured the queen: ‘I talked less sensitively than I should have about the need to learn lessons.’

Despite the heated emotions, a state funeral was belatedly agreed for 6 September, bringing the immediate frenzy to an end. The first-class post across the country was held back for an hour to await the issuing of two thousand invitations to the grand event. When the deadline was missed, the nation’s entire fleet of Post Office vans was commandeered for their special delivery.

On the eve of the funeral, as thousands of grieving spectators bedded down along the route and outside the Abbey, the only unresolved detail was whether Charles and his sons would walk behind Diana’s coffin on its one-hour-and-forty-seven-minute journey from St James’s Palace. During an earlier discussion with Blair’s aides, Prince Philip, speaking on the phone from Balmoral, had exploded about the spin doctors’ insensitivity: ‘Fuck off. We are talking about two boys who have lost their mother.’ The question was finally resolved over the family dinner on the night before the funeral. To break the deadlock, Philip said to his grandsons, ‘Well, if you don’t go, I won’t.’ The boys decided to walk behind the coffin with their grandfather, their father, and Diana’s brother Charles, the ninth Earl Spencer.

While the Windsors debated, Charles Spencer visited the Abbey to rehearse the words he would deliver from the pulpit the next day. He had written an outspoken rebuke to the royal family, but after spotting a lurking palace official he decided to remain silent. His idea that Tony Blair rather than Prince Charles should read the lesson had been rejected, which made him only the more determined. At the funeral the following morning, his accusations against an astonished royal family divided the nation. Some were outraged at Spencer’s impudence, while others praised his courage. The art historian Roy Strong, taking his cue from the public’s loud applause which could be heard inside the Abbey, wrote that the people ‘want a monarchy but they want it human and compassionate. The present cast suddenly looked past its sell-by date.’

Spencer’s feelings of enmity towards Charles continued during Diana’s interment at Althorp, the Spencer family home, at the end of the day. Afterwards, according to Paul Burrell, the earl’s speech was being replayed on television in the room where the prince was offered tea. As the ex-brothers-in-law talked together, Charles volunteered that while Spencer had inherited his title as a young man, he himself had already had to wait decades before becoming king. When details of the conversation appeared in the press, Spencer was accused of leaking the exchange, and Burrell of fabrication because there was allegedly no television in the room.

By the following morning, Spencer’s denunciation of the Windsors was overshadowed by the testimony of those who recalled that Diana had accepted Harrods owner Mohamed Fayed’s invitation to holiday in France only after her brother, citing potential media intrusion, had withdrawn his agreement that she and her children could spend the summer on the Althorp estate. The desperate mother, according to her admirers, had been abandoned by both her families.

Charles was more melancholic than ever. His popularity rating was stuck at 4 per cent. Critics mocked him without appreciating his insight into the truth. He was receiving, he complained, no credit for carrying the intolerable burden of duty to serve the irredeemably ‘awful’ monarchy, and feared the public’s reaction when he finally emerged from his seclusion at Highgrove. Determined to believe that life without guilt was possible, he decided that his task was to resurrect himself and his lineage. Buoyed by the solid support he always received from the queen mother, he would never renounce the crown. While the queen offered continuity, dignity and traditional values, his fate depended on somehow using Diana’s death as a catalyst to overcome his unpopularity.

Disliking Blair’s announcement that the royal family intended to ‘change and modernise’, conjuring up visions of a Scandinavian bicycling monarch, Charles was seeking a formula for reinvention without abandoning the trappings and advantages of royalty. During discussions at Highgrove, he asked his staff, ‘How can we get the public to understand what we do? We need to be more accessible. But we must still keep our distance, and must not be like the public.’ In reply, Tom Shebbeare, the chief executive of the Prince’s Trust, suggested that Charles should speak publicly about Diana. Charles frowned. He shared his family’s anger that his ex-wife was being mythologised despite being, in his words, ‘a nutter’.

Dignity demanded that the battle of the Waleses should be buried. Other than uttering praise of Diana, Charles would remain silent. Simultaneously, any activity that risked him being portrayed as the ‘playboy prince’ was to end, and the campaign to have Camilla made more acceptable suspended. ‘Emphasise service, one’s duties and contribution,’ Charles told his staff. The media should be directed towards his various initiatives to do good for the country. ‘And please keep pushing them,’ he ordered. In parallel, Stephen Lamport was told to ask Peter Mandelson and Anji Hunter, the prime minister’s adviser in Downing Street, to arrange for Blair to make speeches in praise of Charles.

‘Nothing happens by chance,’ Mark Bolland concurred. ‘Everything has to be engineered.’

Mandelson duly briefed Jon Snow, the Channel 4 news presenter, that it was Charles’s initiative to fly the flags at half-mast, and that only after he had argued his case with the queen and Robert Fellowes was Charles allowed to organise ‘a full royal funeral at Westminster’. The resulting impression, said a satisfied Bolland after Snow’s ‘exclusive’ broadcast, was ‘Charles at the helm’. As requested, Tony Blair added his blessing during a television interview, stating that despite the Church’s disquiet about his divorce, Charles would not only be king, but also the supreme governor of the Anglican Church.

‘The world is run by some very nasty, powerful people,’ Charles had written to Jonathan Dimbleby. ‘Enemies of mine’, he warned, would become Dimbleby’s enemies. He had also consoled Camilla about the consequences of their relationship: ‘You suffer all these indignities and tortures and calumnies.’

Two broadcasts alone could not halt the opprobrium that was threatening Charles. On a personal level, one salvation was the spiritualism of the poet Kathleen Raine, who had been introduced to Charles by Laurens van der Post. Listening to the prince’s laments about his isolation under siege and his forlorn search for meaning, this unusual woman, who lived an unorthodox life in London and was forty years his senior, offered comfort over cups of tea in her Chelsea house. ‘She was always there for me because above all she understood what I was about,’ Charles explained, voicing his attachment to much older people, ‘and that was a profound comfort in an age of growing misunderstanding and almost deliberate ignorance.’

Raine urged Charles to disregard his critics: ‘Dear, dear Prince, don’t give that riff-raff an inch of ground, not a hair’s breadth; stand firm on the holy ground of the heart. The only way to deal with the evil forces of their world is from a higher level, not to meet them on their own.’

Raine’s spiritualism, based upon what she called ‘prayer in action’, the worship of the sacred nature of all life, art and wisdom, buttressed Charles’s sense of superiority. In his vision of himself as the protagonist in his own tragedy, and freed from any sense of shame, Charles adopted a formula for survival taught at the Temenos Academy, a charity of which Raine was one of the founders, that divided faith into metaphysics, mysticism and visionary imagination. Casting himself as the exceptional hero, Charles later explained his bravery in a eulogy he delivered at Raine’s memorial service: ‘I had put my head above the parapet and, yet again, the shells and bullets had been exploding all around me … The world seemed to be periodically madder and the powers of darkness – as Kathleen described them – closed in. She did her utmost to reawaken an Albion sunk in deadly sleep.’ Feeding his self-indulgence, Raine wrote: ‘How my heart rejoices that you have mounted that chariot. The chariot of fire between two armies. This is the great battle and where would you, our prince, rather be than in that chariot?’ Most sane fifty-year-old men would have ridiculed Raine’s inflated rhetoric, but Charles inhaled her words like oxygen.

To survive in the real world, he needed to ignore the risks and make himself visible. Four weeks after Diana’s death, he agreed with some trepidation to visit a Salvation Army centre in Manchester. He arrived with a speech drafted by Downing Street’s best spin masters, including Peter Mandelson, but then set it aside. Instead, he spoke with unscripted passion to a group of curious spectators. Repeatedly telling them how ‘enormously grateful and touched both the boys and myself have been’, he was at his best. The media coverage described a loving father of two adored sons speaking from the heart about their grief and grateful for the public’s support.

This sympathetic press coverage persuaded Charles to take the thirteen-year-old Harry – who was on safari in Botswana with Geoffrey Kent to alleviate his misery – on a trip to South Africa arranged months earlier by the Foreign Office to meet Nelson Mandela.

‘Speak to the media and be friendly,’ Mark Bolland advised Charles.

He also told Robert Higdon, ‘He wants to raise money while he’s there.’

‘You’re mad,’ replied Higdon, ‘but I’ll try.’

Higdon approached Mary Oppenheimer, scion of the diamond-mining family, to host a dinner for thirty people, including a number of South Africa’s billionaires, prepared to contribute to Charles’s Global Foundation. ‘It was always about money,’ recalled Higdon, who was delighted by the event’s success and by Charles’s praise. Some years later, he revised his opinion: ‘The atmosphere to extract donations from the guests was very awkward.’

Media coverage of Diana’s son happily meeting South Africa’s hero, who had also invited the Spice Girls, liberated Charles. On the return flight to Britain, he offered journalists his new manifesto: ‘Tradition is a living thing but to be so it has to be made contemporary in each generation. That is always the great challenge.’ A few days later, a South African friend of Charles’s wrote reporting Mandela’s admiration of him. ‘How wonderful,’ he replied. ‘Why do foreigners praise me but my countrymen never share that feeling?’

He believed that Peter Mandelson could provide the solution. Their relationship had strengthened in the weeks after Diana’s death. Reflecting on Mandelson’s recent defeat in elections to the Labour Party’s National Executive Committee, Charles commiserated: ‘It only goes to show, I suppose, what a ghastly, cut-throat business politics is. The throwing of knives into other people’s backs seems to be a pretty prevalent blood sport and it is not a pretty sight. But then, you would perhaps expect the representative of an “outmoded” hereditary organisation to make such an observation.’ He added that he wrote as ‘a person who, despite the inevitable outer carapace which has to be worn to confront the world, nevertheless has a rather vulnerable and sensitive inner core’.

Mandelson was an obvious guest for one of Charles’s ‘culture weekends’ at Sandringham that autumn. Others invited (the guest lists for many of these weekends were orchestrated by the philanthropist Drue Heinz) included Tate director Nicholas Serota, novelist Angela Huth, barrister Ann Mallalieu, Leo Rothschild and Stephen Fry. Clever, funny and endlessly flattering, Fry had an erudite wit that delighted Charles. ‘No one complains on his deathbed,’ Fry told the guests, ‘“Oh God, I wish I had spent more time in the office.”’

‘You’ll need black tie and white tie, clothes for walking,’ one guest was advised. Asked about attending church on Sunday, the official replied, ‘There’s no obligation to go, but if you don’t you’ll be ignored during the following lunch.’

All of this was in the spirit of the royal family. Sandringham formality had been inherited by the queen from her father and grandparents – even on Christmas Day she expected perfect behaviour from her grandchildren. Charles’s literary weekends were no different. Although he had not engaged with intellectuals during his time as a student at Cambridge, he enjoyed their company. ‘Of course, I know very little about this,’ he would say in a self-deprecating manner after mentioning paintings he had bought by little-known artists. His guests would depart on the Monday morning with a sense of privilege and memories of a remarkable performance by their host.

Charles had remained silent about Camilla’s absence. She was, he knew, suffering under the strain. ‘She’s a wreck,’ he told a friend, and half-joked to Bolland that in the past he would have been sent into exile and Camilla committed to a dungeon. All he wanted, he told those whom he regularly telephoned, now including Mandelson, was the chance to go out in public with the woman he loved.

By Christmas, the worst was over. The trip to South Africa had placated some critics. In one poll, 61 per cent of those who responded said they were satisfied with Charles, compared to 46 per cent before Diana’s death and that 4 per cent immediately after. The dissatisfaction rate had fallen from 42 to 29 per cent. These figures restored some sense of Charles being master of his destiny. His advisers spoke about rebuilding his reputation after a doomed decade. In the new era, he anticipated that an open relationship with Camilla would be possible, despite other polls that showed about 90 per cent of Britons still opposed their marriage.

One obstacle was Robert Fellowes. In a court corroded by inertia, he and the queen were struggling to estimate the damage caused by the ten-year crisis. Neither Charles nor Camilla saw any possibility of a normal life together unless the queen approved, and that was impossible until Fellowes was no longer there to advise her.

Charles’s machine went into action. The poison was planted in the Mail on Sunday. On 2 November 1997 the newspaper published an attack under the headline ‘Another Royal Farce … Carry On Sir Robert’. The article, by Peter Dobbie, a regular columnist, accused Fellowes of being prejudiced against Charles for wanting to live with Camilla. Worse, he was accused of being ‘a joke’ who ‘evokes loathing’ for having been ‘one of the prime instruments in the destruction of the monarchy’s public esteem’. Fellowes was singled out for blame for the ‘public perception of uncaring, dysfunctional senior Royals’ after Diana’s death. Dobbie ended with the knife-twist: ‘By staying on he can only perpetuate his views of outdated incompetence born of arrogant indifference.’

‘Robert’s been stuffed by Bolland’ was the word around Downing Street. Naturally, Fellowes was furious. His friends in Buckingham Palace blamed Charles for wanting to destroy any courtier who opposed his demands. To save himself, the prince had infected the royal palaces with jealousy, vulgar extravagance and deceit.

Fellowes saw no obvious solution. One immediate remedy would be to surrender to the media attack. His departure could be seen as justifiable. The queen needed a new, candid friend to whom she could unburden herself and be advised how to satisfy her headstrong son. In the inevitable negotiations between the palaces, Fellowes was not ideally placed to suggest sacrifices. He and the queen agreed that after seven years’ service he should move on; the transition should start for Robin Janvrin, his deputy and a former Foreign Office diplomat, to succeed him.

For his part, Janvrin was immersed in plans for the queen’s Golden Jubilee in 2002, which he hoped would restore the monarchy’s reputation after a decade of disaster. Securing the queen’s approval for the celebration was an uphill battle – the public, she said, were unenthusiastic about the monarchy. But persistent pressure gradually wore down her reluctance. However, retaining her trust depended on months of serenity. There could be no more scandals.

Charles’s fate partly depended on the celebrations restoring the romance of the monarchy. Although he himself was not obviously imaginative, Janvrin shrewdly understood how to draw on other people’s ideas to make an impact. Among the spinoffs of the Jubilee, he believed, would be a challenge to those courtiers who ignored the public’s loss of trust in the ‘unworthy’ royals. Too many members of the royal family were living off the civil list, receiving police protection and revelling in the free use of private planes, royal trains, boats and castles. Family ties and relationships were bedevilling attempts to persuade these ‘unworthy’ royals to draw the line voluntarily. Too many of them had too much to lose, especially some of the young royals who demanded privilege and pomp while simultaneously making sham pleas to be treated like everyone else.

A by-product of the Jubilee would be to curb the legacy of the imperial era. More profoundly, here was the opportunity to signal the transition from a belief in the queen’s divine right to rule, as affirmed at her coronation in 1953, to Charles’s wish for a multi-denominational, inter-faith coronation. Although that was constitutionally impossible, negotiations for a compromise would open discussions about whether Charles’s heirs could marry Catholics, and whether a first-born female child could succeed as queen.

Overcoming the obstacles to a constitutional debate depended upon neutralising the queen’s dislike of change. ‘Well, my father told me this …’ she would still regularly say. Wedded to George VI’s influence and with the queen mother urging the most reactionary decisions during her daily telephone calls to her daughter, the queen was shaped by Edwardian precedents. Rigidly conservative, she refused to allow even moving any furniture in Balmoral from the place assigned by Queen Victoria. Charles, she feared, would change everything, not least out of pique. ‘My son,’ she once complained to a nobleman, ‘resents me because I taught him the alphabet.’

On many matters she would defer to her husband, who was well aware of the problems they all faced. ‘Throughout history,’ Philip told an adviser, ‘there’s been a difficult relationship between monarch and heir. It’s not a job but a predicament.’ He wanted his children to follow his way of doing things, but knew that Charles would not forgive his father’s apparent ‘sins’ – including his ordering Charles, as a child, to wear corduroy trousers to a birthday party, the only one present to do so. Even as a middle-aged man, Charles still felt the legacy of that trivial humiliation. He also lacked his mother’s genius for concealing what she truly felt and separating her personal values from those of the nation. He would never be able to emulate her landmark speech at a lunch in Whitehall to celebrate her golden wedding anniversary in November 1997, when she had volunteered that the monarchy’s existence rested on popular approval – adding, to applause, that she herself was willing to change after listening to the public.

Charles disliked those sentiments. He preferred to confront anyone he disliked, regardless of the fallout. Unlike his mother, he failed to provide a sense of solidarity or stability. He did not stand as a symbol of the country and its heritage, or personify an idea. Not astute enough to create illusions when needed, or to float above the rancour, he was content to pose a threat.

Negotiating peace with the unpredictable heir was complicated by the appointment to head the queen’s household of Lord Camoys, a banker from an old Roman Catholic family, as the lord chamberlain. To Charles, Camoys represented the old guard, with its antediluvian understanding of the monarchy. His dislike was exacerbated by Camilla’s complaint that Camoys had once accused the Parker Bowles children of cheating in a school race.

Since the 1980s, Charles had sabotaged every attempt by the queen’s advisers to coordinate their two courts. To him, Buckingham Palace was not a homogeneous organisation. In his opinion, little had changed since he was born. Within the immutable layers of rank, right down to the servants who laboured in the basement of the palace, there was unyielding respect for the queen and fear of her displeasure, but also an understanding that individual power depended on every courtier’s relationship with his or her immediate superior, the high value of intimate information, and ultimately access to the queen. Charles’s disdain for that culture was magnified by his dislike of Fellowes, Janvrin and now Camoys.

Janvrin’s hope that he could fashion a new relationship with St James’s Palace rested on Stephen Lamport’s skill in persuading Charles to resist his instincts and stabilise his relationship with Buckingham Palace. But that depended on Charles’s whims. Giving honest advice to a man who would explode when contradicted was no easy task, especially as the prince once confessed, ‘My problem is that I believe the last person I spoke to.’

Unlike the queen, Charles frowned on people with different ideas from his own. While her lack of dogmatism encouraged free discussion, he was closed to alien thoughts. Every day his public and private life threw up difficulties, and every day Lamport tried to tone down Charles’s opinions, especially about the environment, education and fox-hunting – although after their lunch at Highgrove, Peter Mandelson had told journalists that any private member’s attempt to introduce legislation banning hunting would not be supported by the government.

In their daily meetings, Lamport tried to measure Charles’s intentions in comparison with the precedents established by his predecessors over the previous two hundred years. He then gave advice, but he could not always gauge Charles’s reaction. To reach the ideal decision on almost any matter required him to follow a convoluted and uncomfortable route. If his advice were rejected, Lamport suffered in isolated silence: ‘I blame the vipers’ nest in Charles’s private office,’ observed an official in Buckingham Palace about the tortuous process. There were layers of hierarchy, with everyone attempting to climb the greasy pole. Whatever was said, one never knew how far it might go, ‘who could be trusted and how it would be twisted’. Buckingham Palace and St James’s Palace suffered from identical manipulative tussles.

Uncertain about the best course, in the summer of 1998 Janvrin and Fellowes invited Alastair Campbell for lunch. Charles’s stubborn grudge, they confided, was a tough, long-term problem made worse by their distrust of Bolland. True to his conviction that ‘spin’ was the answer to most difficulties, Campbell urged the two to ‘get a grip’ and embrace a new generation by appointing Simon Lewis, a Blairite public relations expert. On Campbell’s recommendation, Janvrin immediately hired Lewis as Buckingham Palace’s new spokesman. Unlike his predecessors, Lewis was told to bridge the gap between the monarch and the people – or, at least, to break the mould.

Adopting the Blairite tactic of targeted messages, Janvrin believed, would modernise the brand and help define the monarch’s renewed contract to serve the country. Inevitably, some courtiers were puzzled that he was putting so much faith in a New Labour marketing man with no experience of the royal family. Janvrin replied that Lewis and Camoys would repair the monarchy’s vulnerability. As the first anniversary of Diana’s death approached, he feared renewed damage from the tabloids.

Lewis, as a newcomer, struggled to understand the tension between the palaces. Hearing critical comments in Buckingham Palace about Charles’s weaknesses, the contamination caused by Camilla, and how Bolland was promoting the prince at the expense of other members of the family, bore little resemblance to Westminster’s wars. Lewis’s proposals to start lobby briefings, issue statements, send an annual report on the queen’s behalf to twenty million homes, and harness Buckingham Palace to Cool Britannia (New Labour’s gospel to revolutionise Britain) bewildered Janvrin’s critics. He replied that changing the culture was essential to prepare for a modern monarchy.

Charles disagreed. Conjuring an air of change was merely colourful spin, in his opinion, and ignored the House of Windsor’s instinct for self-preservation. Ever since the Saxe-Coburgs had reinvented themselves as the Windsors in 1917 to avoid the fate of the Tsar of Russia, the Kaisers of Germany and Austria and the downfall of other minor European monarchs, the queen had separated herself from Britain’s aristocracy. Unimpressed by titles, the royal family was aware of the country’s hereditary families only if they were genuine friends or were criticised by the media. The natural order, with the monarch at the head of a pyramid supported by the landed nobility, had vanished.

The gentry’s loss of power was of no interest to St James’s Palace. After a decade of gossip and misbehaviour, Charles’s household yearned for a period free of notoriety. His officials’ expectations were frustrated by the prince’s feudal exercise of power, a different kind of misbehaviour.

Some long-term employees who had been granted a home were obliged to receive a visit from Charles as a reminder of their place in the scheme of things; others were invited for dinner, or to a garden party at Highgrove. Lesser mortals received gifts. The prince dispensed presents, graded by his opinion of their importance, to paid and unpaid employees: whisky glasses engraved with his motif, or designer salt and pepper grinders. A typed letter signed by Charles was welcome, but the greatest trophy was a handwritten message in black ink. The universal fear was his expression of displeasure, signalled by the absence of a ‘please’ or ‘thank you’. Finely calibrated blanking – like a Mafia don’s kiss of death – was an overt threat to the courtier’s job, income, school fees and self-respect. After dismissal, there was nothing. Being cut off without even a much-prized Christmas card to acknowledge the relationship was ‘so hurtful’, repeated all the casualties. Charles had made himself clear that they were no longer useful. Loyalty was always a one-way street.

Preferring to live at Highgrove to enjoy his garden and to be near Camilla, Charles summoned people to drive the two hours from London for even the briefest meeting, and would regularly keep them waiting. Yet few refused. The outstanding garden, more than thirty-five years in the making, had been designed by a succession of experts. Molly Salisbury, Rosemary Verey, Miriam Rothschild, Julian and Isabel Bannerman, one after another, were enlisted to fill the landscape with trees, hedges, wildflowers, fountains, rare breeds of farm animals and architectural features, all blended into a romantic safe haven. In return, the heir to the throne offered conditional gratitude. Professional gardeners were divided about the extent of Charles’s own contribution.

Roy Strong was summoned to advise on the cultivation of hedges. He spent days with his own gardener perfecting his ideas. At the end, he submitted his employee’s bill for £1,000 – and was never asked to return, or even thanked. Strong had personally inscribed a copy of his book on gardening to Charles, but it was left in a waiting room rather than included in the prince’s library. ‘He’s shocked by the sight of an invoice,’ Strong noted. ‘So he likes people who don’t charge for their services.’ Inevitably, none of those advisers was individually thanked after Charles received the Victoria Medal of Honour from the Royal Horticultural Society, presented by the queen for his services to gardening, in 2009.

‘Grace and favour’ took on a new meaning. To make up a floragim (a book of paintings of Highgrove’s flowers), Charles recruited over twenty artists to paint two or three flowers each, for free. Similarly, he approached Jonathan Heale, a woodcut artist, for some of his work, which he expected to be donated as a gift. One of the few artists known to have rebuffed similar demands was Lucian Freud. Would Freud swap one of his oils – which sold for millions of pounds – for one of Charles’s watercolours? ‘I don’t want one of your rotten paintings,’ Freud replied.

Strong, despite the rebuffs, narrated a BBC TV documentary about Highgrove. He intended to report that Charles had followed fashion by asking Molly Salisbury to build a ‘potager’ – a vegetable garden, but his draft commentary was returned from Charles’s office with the rebuke, ‘His Royal Highness never follows fashion.’ Strong removed the comment. Charles, clearly, stood ‘above fashion and is always right’. Thereafter, Strong stepped back: ‘I stayed on the edge with Charles. It was less dangerous.’

In the same spirit, in 1998 Charles called Tim Bell, Margaret Thatcher’s media adviser, to ask whether he could borrow Elizabeth Buchanan, employed by Bell to develop relationships with Conservative politicians and bankers, for three days a week. ‘You can’t turn down a royal summons,’ said Bell, knowing that Charles would not pay Buchanan’s salary. Buchanan went to work at the royal home.

Charles had chosen an utterly devoted woman. ‘Elizabeth curtsied lower than anyone thought possible,’ one household member noticed, ‘and then for longer than necessary. She worked all the hours God gave and then some God hadn’t thought about.’ Dubbed ‘the virgin queen’ by her fellow staff, she understood the ritual, the pattern and the access Charles expected. He would sit for hours, and sometimes for a whole day, dressed in eccentric clothes in an armour stone garden surrounded by trees and wildflowers, while Buchanan, ‘blinded by devotion’, pandered to his requirements. On occasions when Charles, in the midst of a meal, took exception to the conversation – especially criticism of his opinions – and stormed out, she was summoned by Michael Fawcett to smooth things over with the guests and to placate the prince. When Charles, near the end of a seemingly pleasant dinner, abruptly headed to his study to spend hours handwriting letters late into the night, it was Buchanan who made excuses to his guests. Tim Bell was unsurprised when she became a full-time employee. Her salary did not reflect her new position as an assistant private secretary, but the media man quietly bridged the gap.