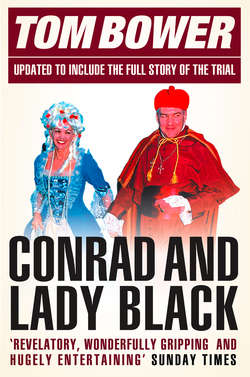

Читать книгу Conrad and Lady Black: Dancing on the Edge - Tom Bower - Страница 6

INTRODUCTION The Wedding, 26 January 1985

Оглавление‘Six months at most. I give this marriage just six months.’

‘Come off it, Posy. How do you know?’

‘Because I lived with David Graham in London. Every night he came home with a different girl.’

Posy Chisholm Feick, a sixtyish Canadian travel writer and socialite, had grabbed the attention of every guest around the table: ‘They came in every shape and size. Even a black girl with a shaved head.’ The band struck a high note in the crowded ‘Stop 33’ room at the summit of Toronto’s Sutton Place Hotel, but, encouraged by her audience, Posy continued uninterrupted. ‘I saw them every morning. He’d rush off to work, leaving the girls to struggle by themselves.’

‘So what?’ asked Allan Fotheringham, the veteran political columnist.

‘Well,’ smiled Posy, with the confidence of an expert in sex and marriage, ‘one of them said he’s a lousy lay. Barbara won’t like that.’ Eyes narrowed and mouths pursed.

‘Just hold on for the ride,’ smiled Peter Worthington, the editor-in-chief of the Toronto Sun.

‘Barbara wants what’s best for Barbara,’ added one man, recalling painful rejection. ‘She’s too restless,’ sighed another failed suitor. ‘And David’s so boring,’ chimed a new voice.

‘Let’s take bets,’ said Posy, spotting the bride swaying in her white, backless Chanel dress. Posy’s wager was certainly high, but the loud Latin American music and the alcoholic haze prevented anyone hearing the size of Allan Fotheringham’s risk. ‘It won’t last long,’ shouted Posy, throwing back another glass. ‘She’s a wild and crazy girl,’ said Fotheringham, speaking with the benefit of carnal experience of the bride. ‘She’s got an eye for the big chance. This is it. She won’t let it go.’

The forty-four-year-old bride now interrupted the jousting at the large round table. After fluttering around a room filled with sober politicians, famous millionaires, rich professionals and Canada’s media moguls, including Conrad Black and his wife Shirley, Barbara Amiel appeared to welcome the sight of the group of rowdy journalists. For twenty years that crowd had represented her social and professional background, but her marriage indicated her removal from them. Famous throughout Canada as an opinionated columnist, Amiel had just resigned as comment editor of the Toronto Sun to join her third husband, David Graham, in London. The rollercoaster years of drugs, adultery and emotional mayhem were over. She was, she had admitted, ‘ashamed of my personal life’.1 She had shared beds with too many ‘beach boys and wildly unreliable bohemians’. They were good for ‘steamy novels but short unions’.2 Years of notoriety would be replaced by domesticity, motherhood and fidelity.

For the uncynical at the wedding party, Barbara Amiel’s choice was understandable. David Graham was handsome and seriously rich. Shrewd investments in the fledgling cable network business had produced a company worth US$200 million,* and homes in Toronto, New York, Palm Beach, St Tropez and London worth another $100 million. For the former middle-class north London girl known to plead, ‘My father was very poor and unemployed,’ the prospect of returning home in style was irresistible. Graham’s motives also appeared unimpeachable.

Barbara Amiel was renowned not only for her beauty, wit and intelligence, but also, among the favoured, as a remarkable sexual companion. ‘Sex is great with Barbara,’ confirmed one of her wedding guests. ‘A great body, and her breasts are big and beautiful. Like lovely fried eggs.’ ‘Yeah,’ agreed another connoisseur. ‘She wants to be admired for her brains, but she keeps pushing her breasts into men’s faces.’ Amiel would be the first to admit that sex, ‘the key to our entire being’, was her trusted weapon.3

During the evening, for most men gazing at a seemingly tough, unemotional personality, Amiel’s thin waist, long dark hair and Sephardic looks were alluring but unobtainable. Only David Graham and her former lovers realised that her harshness was a masquerade, honed during a tough battle for survival, to gain protection from rejection. Behind the façade the bride was a vulnerable woman, desperate to fulfil her lovers’ fantasies. Like cosmetics applied every morning, she relied on her chosen man’s image to project herself. After dallying in the past with left-wing politics, a hippie lifestyle and impoverished men, she had chosen to be reincarnated by marrying class, wealth and looks. ‘You can’t believe how good David is in bed,’ she had said to a girlfriend just days before her wedding, with seeming conviction. ‘I couldn’t do without this man. I had to have him.’

Few believed that Graham, a quiet, unexciting man, matched Amiel’s description. Rather, many assumed, her head had been turned after researching an article for Maclean’s magazine entitled ‘Who’s Who in Canada’s Jet Set’. Gushingly, she had written that the rich, with their private planes and pampered lifestyles, ‘live our fantasies in a world which has no borders, just locations’.4 To join that world, she had decided to ‘marry up’, a phrase she would use in the headline of a subsequent confessional article.5 The ‘trade-off’, she admitted, was crude: ‘her looks for his money – his power as her meal ticket’. Together, Barbara Amiel and David Graham could present themselves around the globe as a ‘power couple’, rich and influential.6

Established ‘power couples’ were scattered across the Sutton Place’s party room. Sitting with Ted Rogers, head of the Rogers Communications empire, was Conrad Black, the owner of an expanding newspaper group. Like many of Canada’s establishment, Rogers praised Black’s intellect, but voiced suspicions about the pompous businessman’s eagerness to make money. Branded as a ‘bad boy’ or a ‘bad joke’, Black had not won admirers since saying in the early 1980s, ‘Greed has been severely underestimated and denigrated, unfairly in my opinion … It is a motive that has not failed to move me from time to time.’ Strangely, he seemed impervious to the impression his admission had created. Bad publicity was nothing new to the ambitious Black. Over the previous two decades, while seeking the spotlight as a supporter of right-wing causes, the aspiring media baron had placed himself in many firestorms. His outspokenness was a characteristic which he shared with Barbara Amiel.

Black’s admiration for the bride was curious. Professionally, she represented much that he despised. Rather than writing on the basis of careful, measured research, she was famous for spewing out gut prejudices. Years earlier, her left-wing sentiments had been interpreted by Black as envy of the rich and powerful, but after changing boyfriends, her politics had somersaulted. The former Marxist had changed colours, and now chanted her praise for capitalism. Meeting Amiel for the first time at a dinner party in Toronto in 1979 had converted Black into a fan. How could he resist a woman who professed her admiration for his blockbuster biography of the right-wing former Premier of Quebec, Maurice Duplessis? Like so many men in ‘Stop 33’ that evening, he had become enamoured of her star qualities. There were also similarities between them.

Conrad Black and Barbara Amiel had both been afflicted by depression, insecurity and exposure to suicide. Both their fathers had killed themselves, and both Black and Amiel had had moments of the deepest despair at certain points in their lives. Neither imagined that the wedding reception was a mere interlude before the consummation of their own explosive relationship, but with hindsight their eventual union seems almost inevitable.

Fate determined a strange climax for both of them at the end of the reception. Sharing a limousine, Conrad Black and Allan Fotheringham argued violently, and parted on bad terms. Across town, lying in bed after her wedding celebrations, Barbara Amiel was presented by her new husband with a pre-nuptial agreement that had been drawn up earlier. ‘Sign here,’ said Graham. Amiel did as she was ordered. She was in love.

* Unless the context indicates otherwise, throughout the book monetary values are given in American rather than Canadian dollars.