Читать книгу Dangerous Hero - Tom Bower - Страница 6

Preface

ОглавлениеThe genesis of this book started exactly fifty years ago.

At the end of January 1969, a group of Marxist and Trotskyist students at the London School of Economics led a stormy protest against the school’s director, an authoritarian from Southern Rhodesia. He had ordered the staff to close a series of gates inside the building in Aldwych to prevent a students’ meeting in the school’s Old Theatre. In the mêlée, at about 5 p.m., a caretaker guarding the gates died from a heart attack and the students instantly started a month-long occupation, igniting similar sit-ins across Britain’s universities.

Throughout that first night of occupation, hundreds of LSE students crowded into the Old Theatre to debate the prospects of a Marxist revolution in Britain. Led by American graduates from Berkeley, California, where the student revolt against the Vietnam War had started five years before, and with speeches from French and German students, battle-scarred from 1968 street fights in Paris and Berlin, LSE’s Marxists and Trotskyists (there were many) told us we were the vanguard of a worldwide revolution – which would begin with the students, and the workers would follow. We believed it.

Aged twenty-three and from a conservative background, I had completed my law degree at the LSE (the country’s best law faculty at the time), and while studying for the Bar exams was employed on legal research projects at the college. Long before that dramatic night I had concluded that English law protected property rights at the expense of the rights of individuals and real democracy. Surrounded by articulate Marxists studying sociology and government, and going to lectures by Ralph Miliband and other Marxist teachers, I became attracted to their analysis of society. In that era, for anyone interested in politics that was not surprising.

In the wake of the Sharpeville massacre in South Africa in 1960 (I had marched in protest through London with my school friends against apartheid during the early years of that decade) and the anti-Vietnam protests outside the American embassy in Grosvenor Square in 1968 (along with others, I escaped with just some nasty blows from the police), I shared the horror at the dishonesty and disarray of Harold Wilson’s Labour government. Added to that, for family reasons I was influenced by events in Germany. In particular I became fascinated by Rudi Dutschke, an erudite Marxist who spoke in graphic terms in Berlin about ‘the long march through the institutions of power’ to remove the Nazis and their capitalist supporters from ruling post-war Germany. In April 1968 an attempted assassination of Dutschke illustrated the raw battle for power between good and evil raging across Europe and America. (I would meet Dutschke later in Oxford.)

Those days and nights of long debates about politics, the economy and society were decisive for many of us involved in the LSE occupation. After a month it all petered out, but that 1968 generation was marked for life. None of us attained high office in politics, industry or education. Instead, that seminal moment in Britain’s social history created cynics: men and women who were dissatisfied, curious, nonconformist and determined to expose evil in the world, of whatever type and wherever it might be found.

As ‘Tommy the Red’ (I became a students’ spokesman), that month I learned many vital lessons for the journalistic career I embarked on soon after, travelling for a week on a special train with Willy Brandt during his successful election campaign to become Germany’s chancellor. I emerged from that train with a unique insight about politicians and statecraft. Not least, that every politician is best judged by his or her closest advisers. Thereafter I spent many years producing BBC TV documentaries in Germany (about the Allied failure to prosecute Nazi war criminals and to de-Nazify post-war Germany) and across the world. Witnessing a myriad of wars, elections, corrupt politicians and shady businessmen cured me of Marxism, but not of my curiosity and innate scepticism.

LSE’s Marxist student leaders did not join the conventional world. Some died tragically young, often from suicide, while others committed their whole lives to the struggle for revolution. In researching this book I was reunited with several of them. After fifty years they had changed a good deal physically, but not in their core beliefs. Pertinently, they all genuinely sensed that their Marxist dream would finally come true, delivered by Jeremy Corbyn.

Despite being excited by that prospect, they have no illusions about Corbyn himself. None of those illustrious Marxists who have survived since the 1960s – all intelligent, well-educated, engaged and engaging – recall Corbyn as a major player over any of the four decades before his ascension as leader of the Labour Party in September 2015. On the contrary, although they did not doubt his sincerity, they were underwhelmed by his intellect. In any event, for them, winning power was all that mattered, and like many across Britain’s political spectrum, they were certain that Corbyn would be Britain’s next prime minister.

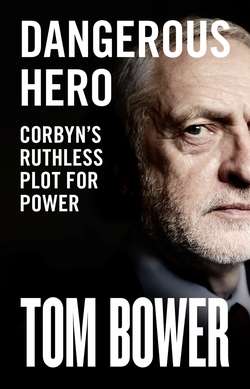

That possible outcome was the reason I wrote this book. With Corbyn having a good chance of victory, the public deserves to know more about him. Surprisingly for a politician, but not for a hard-left conspirator, he has done his best to conceal his personal life from the media – which he loathes.

My main criterion for writing previous biographies has been to identify those at the top of the greasy pole, ambitious to influence our lives but unwilling to reveal their pasts with a reasonable measure of truth. Often they have falsified their biographies to protect themselves from public criticism. Corbyn is no different. Despite his repeatedly stated commitment to improve the lives of the impoverished, fight injustice, champion equality and destroy greed, he has hidden away much about himself that is relevant to judge his character and Britain’s likely fate under the Marxist-Trotskyist government he has always promoted.

There can be no doubt about his passion to improve conditions for his constituents and the less advantaged in Britain and across the world. Frugal in his clothes and his food, he poses as the ‘good idealist’ engaged in a lifelong fight for justice and equality. In varying degrees, that aspiration is common to every politician: even tyrants don’t openly promise injustice and inequality. The difference between politicians is in their methods. Corbyn’s credo reflects his abstemious lifestyle. He disapproves of ambition and success. Equating both with greed, he strives not for equality of opportunity, but equality of poverty. In his ideal world, recognising the guilt of its shameful empire, Britain would abolish immigration controls and allow the needy to enter the country to share its wealth. For the rest, by taxation and confiscation of property, Corbyn would irreversibly transform Britain. Inevitably, there would be winners and losers; and until recently he did not conceal his contempt for his quarry. However, in his efforts to win the next general election he has starkly modified his language, and his senior colleagues have followed his lead.

Just how Corbyn became a communist has never been revealed. Before he was elected Labour’s leader he was not seen as a figure of consequence, and thereafter he did all he could to protect the mystery. Since he now offers himself as Britain’s next leader, his background story has become relevant. Is he a danger to the country? How genuine are his beliefs or his public character? Is he as benign as Labour’s spin doctors now insist?

Ever since the collapse of the Soviet empire in 1989, the number of those who advocate Marxism as a system of government has rapidly diminished. No one much under the age of forty-five is a credible witness of the oppressive dictatorships imposed by Russia on Eastern Europe. No one much under sixty can recall the industrial anarchy orchestrated by communist conspirators in Britain during the 1960s and 1970s. Only the far left looks back on that era with any nostalgia. The rest blame the widespread strikes of those years, often orchestrated by Marxists or Trotskyists, for permanent damage to Britain’s economy.

Corbyn disagrees with that assessment. For him, his election as prime minister would be the curtain-raiser to completing the unfinished business halted by Labour’s election defeat in 1979. His admirers, for whom he is a hero, agree. The older ones are resolute socialists; his younger supporters are idealists, ignorant of history. Across that spectrum, few understand the society that Corbyn and his fellow Trotskyists, including John McDonnell, Len McCluskey, Diane Abbott and Seumas Milne, intend to build.

I understand the Corbyn Utopia better than most, because I have spent my life and career among the hard left. At school and in my block of flats in north-west London, I grew up surrounded by the children of communists, and often visited their homes. In the late 1950s I began travelling to communist Czechoslovakia, and as a journalist, between 1969 and the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1990 I frequently travelled across communist East Germany to interview senior officials and study the government archives about the Nazi era. As a BBC TV reporter I spent a lot of time during the 1970s with British strikers, especially the miners led by Arthur Scargill and his fellow Marxist trade union leaders. In 1989 I began three years of work in Russia, interviewing high-ranking Soviet intelligence officers who played the spy game against the West. While filming wars in Vietnam, the Middle East and South America, I constantly encountered hard-left idealists and latterday commissars. As a result I am no stranger to the manoeuvres of Corbyn and his group to seize power, nor to their ambitions once in Downing Street.

This book, told with the help of eyewitness accounts by people who have known Corbyn throughout his life, reveals the nature of the man who, if the Conservatives successfully rip themselves apart over Europe, is set to become prime minister.

The question is whether a Labour government led by Corbyn would transform the country for the better. Has capitalism, as he argues, run its course, and would our lives be improved by socialism? If so, is Corbyn’s socialism the same brand that we have experienced under successive Labour governments since 1945, or something more radical, like a Marxist miracle? Is he a reformer or a revolutionary? And what sort of socialist is Corbyn? His supporters damn every opponent, especially Blairites, castigating each critic, even sympathetic ones, as ‘traitors’ or worse. Does that aggression, and the accusations that paint Corbyn as an entrenched anti-Semite, override his image as an authentic ‘good bloke’ blessed with everlasting politeness. As described in this book, I have found another side of the man. Would his election have a happy ending for Britain? For some, he would be a dangerous hero.