Читать книгу Five European Plays - Tom Stoppard - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

INTRODUCTION

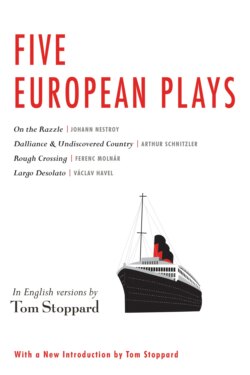

ОглавлениеA translation when commissioned by a theatre is bespoke. There is no common principle uniting these five. Two of them, On the Razzle and Rough Crossing, are so free as to question their claim to be translations at all, yet they are unalike in the liberty they take. In the case of the other three, the goal was an English version as faithful to the original as the translator could make it, but by that measure the results in the event were various, too.

Undiscovered Country is somewhat shorter than the German, partly owing to a decision to perform the play with one intermission instead of Schnitzler’s two. As a translator I don’t recall feeling disturbed on behalf of the author by these cuts, nor by my willingness in rehearsal to alter Schnitzler here and there in small ways to sharpen the pace beyond strict fidelity. As a playwright, of course, I might disapprove but a lifetime in making theatre teaches a degree of latitude. Translating a play is not a job for linguists. This is a position no doubt easier to maintain as a translator of a play than as a playwright in translation. Once, in Italy, watching a play of my own I couldn’t help noticing that a very large chunk of my second act had gone missing. When I enquired about this, the disarming reply was, ‘We thought we would perform what we had time to rehearse.’ So, on the whole, I count Undiscovered Country among the respectful of these translations.

I hope Schnitzler would put Dalliance in the same company. But it has to be said that the third act of Liebelei has been moved from a flat in a poor quarter of Vienna to the wings of the opera house during a rehearsal, complete with tenor, soprano, conductor, stage manager, and unseen musicians. The change was made by the director, and I insist that it was a brilliant stroke. At the end of Dalliance the heroine Christine, one of Schnitzler’s ‘sweet girls’ who exist to be seduced by the young bloods of the town, learns that her lover has been killed in a duel, and she runs off intent on dying on his grave. The imported mise-en-scene did not seem out of place, Christine’s father being a musician at the opera, and the duet between the unwitting singers turned the screw on the scene. Perhaps it was the singing that pushed me to an excess of ‘translation’, Christine’s final speech of vituperation. Looking now at these three invented lines, I would say they observe the spirit if not the letter. And having said so, I must add that by coincidence I have been reading ‘a translation manifesto’, Sympathy for the Traitor by Mark Polizzotti (2018) which quotes a nineteenth century critic thundering, ‘The instant a man says, “I will give you the spirit of the author …” it is all over with the original. Translation, in such a case, becomes a mere cover for individual egotism and vanity.’ Touché! But I won’t go back on my words. I can hear myself now, in rehearsal, making the case for Christine putting the boot in on her exit. It was 1986, and I was in no doubt I was serving the play, the character, the author, and the times; thus perhaps adding presumption to egotism.

Undiscovered Country and Dalliance were directed by Peter Wood, who knew Vienna and worked a few times at the Burgtheater, more than once with me as his author. At some point he discovered Johann Nestroy (1801–1862) who flourished as a comic actor and playwright in Vienna during the 1840s and ‘50s. Nestroy was prolific but wrote as a Viennese for Viennese, and it’s mainly in Vienna that his flame still burns, for his immersion in dialect and his inventive way with language make him, it has been said, ‘untranslatable, even into German.’ On the Razzle is an adaptation of Einen Jux will er sich machen, which is one of Nestroy’s most loved plays at home, as well as having a secret life almost everywhere else because it is the source of The Matchmaker, by Thornton Wilder, which was turned into Hello Dolly! The story is the mythic tale of two country mice escaping to town for a day of illicit freedom, adventure, mishap, and narrow escapes from discovery, with enough sub-plots to keep everything lively. Having grasped the mechanism I pretty much liberated myself from Nestroy’s dialogue and, so to speak, went on the razzle. En route for the National Theatre, we opened the play at the Edinburgh Festival, where the local authorities veto’d the ‘flaming pudding’ called for in my text. This was a blow. The ‘flaming pudding’ came at the climax of the restaurant scene. I suggested electric candles on a birthday cake and re-wrote to make it Madame Knorr’s birthday, and that’s how the play remained.

Rough Crossing has its origin in a play by the Hungarian Ferenc Molnár, which under the title The Play’s the Thing was presented in Great Neck, Long Island, New York, in 1926, ‘for the first time on any stage in any language’, as asserted in the Samuel French edition. In 1948, The Play’s the Thing, ‘adapted from the Hungarian by P.G. Wodehouse’, was a hit on Broadway. A literal translation of the Molnár was sent my way by Peter Wood and the National Theatre as a follow-up to On the Razzle. The Molnár, titled in translation Play at the Castle, is set, as is the Wodehouse, in a palatial house on the Italian Riviera. Rough Crossing is set on an ocean liner, and that’s not all: it includes my debut and swansong as a songwriter, music by André Previn, and a lot of ocean liner jokes. As I said above, a translation in this business is a bespoke affair. I elaborated the role of the ship’s steward for the actor (Michael Kitchen) who had unforgettably played the manservant in On the Razzle. It’s the steward who has the line which I remember as a shaft of light on the mysteries of live theatre. His employer asks him, ‘When do you sleep?’ The steward replies, ‘In the winter, sir.’ This little exchange is tucked away in Molnár’s second act, and I was intrigued and puzzled that Wodehouse had promoted it to be the curtain line of act one. The first time Rough Crossing was performed and ever after, the line was received with a gale of laughter, occasionally with applause. It was surefire. Did Wodehouse anticipate its effect, or did he move it astutely when he experienced it in action? Peter and I, however, did not move the line, for we already had our first act curtain. It was a song. Like the good ship SS Italian Castle, we had moved a long way from Molnár.

In sum, Largo Desolato is the only one of these five translations to cleave to its original, down to its very punctuation (Havel ends speeches with a dash instead of a full stop). The fact that the author was still living would have been reason enough, but there was more. I was personally invested in Havel’s play, which he dedicated to me. I met him in 1977 when he was under house arrest at his home in the country outside Prague. He wrote Largo Desolato in 1983 when he had been released from prison but was under constant surveillance. I was in no mind to serve his play through judicious cuts or ‘brilliant strokes.’

Peter Wood and I worked together on at least a dozen occasions from Jumpers (1972) to Indian Ink (1995), taking in the first performances of Travesties, Night and Day, The Real Thing, Hapgood, and—in Vienna—the first German Arcadia. He was a teaching director, and I learned from watching him teach. He could be quiet and meditative, but his style was gregarious verging on flamboyant. His mode of address was theatrical verging on scatological. His rehearsals were full of jokes and laughter, too full, I sometimes thought, but sometimes he would make an actor cry. Actors, especially young actors, adored him, and the ones who didn’t vowed never to work with him again. He was a serious cook, which was a big plus for our working suppers in Warwick Avenue, and a serious gardener in his Somerset village, where latterly he liked to spend most of his time, with his dog True and his parrot Mrs. Siddons (inherited from one of his productions). Peter’s eightieth birthday party was in the village hall, attended mostly by villagers with just a few theatre folk from London. He told us how, as a country boy in town for the first time, he was at Liverpool Street station, en route to an interview for a place at the University of Cambridge, when a German bomb fell through the glass roof. He got his place at Cambridge, and at dinner in hall when he bowed his head at table there fell ‘a tinkle of glass and dust’ over his plate. ‘What on earth is that?’ enquired an elderly don. ‘It’s the roof of Liverpool Street station’, said Peter. He got to Cambridge and started to direct plays. His was the generation of Peter Hall and Peter Brook. When I was about twenty I saw his work for the first time, a revelatory production of The Iceman Cometh by Eugene O’Neill.