Читать книгу Holding the Fort - Toni Strasburg - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Beginning

ОглавлениеThis was not the first time my parents were arrested – and it would not be the last. By 1960, both my mother and father had been banned and their lives severely restricted. Three years earlier, in December 1956, just days after my brother Keith was born, my father was arrested along with 156 other leaders and charged with High Treason. That trial was still dragging on.

My parents were deeply involved in anti-government politics in apartheid South Africa. They were members of the South African Communist Party (SACP) and the white section of the ANC (African National Congress) – which had to be segregated at that time – and held important positions in both movements. They believed strongly in equality and in the perniciousness of the South African government.

As with all children of political parents, we developed an extra awareness, antennae which picked up on whisperings, meetings and extra tension in our parents. We all knew that below the surface of our lives as ordinary children of white South Africans, we were different. Our parents’ views were not those of most white South Africans. We had been taught not to ask too many questions and to be careful when talking on the phone as the Special Branch listened in on all our phone calls. Some of us older children would sometimes discuss things among ourselves. ‘Did your dad go out last night?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘Must have been to the same place as mine.’ At sixteen, I knew far more about what was happening, and why, than my younger siblings.

My parents had explained to us about the apartheid government and why they were working against it. They explained why apartheid was wrong and that all people were equal. We learned that in other countries people weren’t defined by the colour of their skin, and that people didn’t think the way they did in South Africa. They talked to us about socialist countries and why socialism would make society fairer for everyone. When I was older, my father gave me books to read that explained their philosophy.

Black colleagues of my parents came to our house for secret meetings or had lunch or tea with us. In the South Africa of 1960, this was not only illegal but was considered outrageous by most white people. When I was younger, if I arrived home with school friends, I was sometimes embarrassed to find my parents’ black friends sitting in our living room. My friends’ association of black people was with the domestic workers in their homes. Their families would have been shocked, even horrified, to find black people socialising on equal terms in our home, and I found it difficult to explain the scenario to them. I would tell them that the visitor was a very important person or chief, and this seemed to make their presence more acceptable.

The weeks leading up to my parents’ arrests that April were tense. Both the ANC and Pan Africanist Congress of Azania (PAC) were planning protests against the hated pass laws which forced African men to carry passes, thereby severely limiting their movements. This law allowed the police to stop black men at any time and if they weren’t carrying their passes, they would be arrested.

The Sharpeville shootings were a turning point in South African history and signalled the end of peaceful protest in the country as it became clear that non-violent action wasn’t going to bring about change. A year later, Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), the ANC’s military wing, was formed underground.

A few days after Sharpeville, my mother called me to her bedroom to explain what was happening. ‘The ANC is calling for the whole country to go on strike to protest the killings at Sharpeville,’ she said. ‘We don’t know what will happen, but we think some people will be arrested – and some of us will have to go into hiding for a while. You must be prepared so that you can help with the younger children.’ Neither my mother nor my father anticipated they would both be arrested.

Telling me this made me feel included – and grown up. I watched both my parents carefully in the days that followed, trying to pick up clues as to what was going on. For a few days, life continued as before but we knew we were living in a time of crisis.

My parents, who were involved at a high level in planning protests, knew that the ‘stay-at-homes’ and strikes that were being called would provoke a reaction from the authorities. They didn’t know what the government would do, but they knew it was likely that a State of Emergency would be declared, and dissidents arrested.

A night after Sharpeville, my father received a phone call from Ahmed ‘Kathy’ Kathrada, one of his colleagues in the ANC. Kathy had a coded message for him about rumours of impending police raids. They had a plan, warning various activists not to sleep at home. Arrests were beginning to take place.

In his book, Memory Against Forgetting3, my dad writes:

The Sharpeville storm, far from blowing itself out, is whipping up like a cyclone … Protest strikers are staying away from work and bonfires of burning passes are blazing in the townships.

By the time I had worked through my list, it’s too late to find a place away from home for myself. I decide to take a chance and go home. These alerts often proved false in the past. There is no reason why this one should be different.

It is and it isn’t. There is no night-time knock at our door, but in the morning, we discover there have been raids on homes all over the country and many arrests. Hilda and I spend the day trying to find out which of our friends and political colleagues have been arrested. There’s no way of finding out where those arrested have been taken but police spokesmen have told the press that more ‘detentions’ can be expected.

We don’t doubt that we figure somewhere on the State list of ‘undesirables’ and while arrests are continuing, we are living on the brink. With four children to look after, we can hardly bolt from home, even temporarily. We agree that one of us should sleep somewhere else, away from home, each night.

We have grown so used to living on the edge of crises that we don’t now act with urgency. Inertia has set in. For a few days, we keep up the semblance of normal life for the benefit of the children, even though we know our time is running out.

The day after the arrests, I tell my employer that I won’t be coming to work until further notice. He understands that this is to do with my politics, but not that I am telling him my world is about to implode. It’s five months before he sees me again. In downtown Johannesburg, there is nothing to suggest the country is teetering on the brink. Business life is going on as normal.

In the days that followed, several leading figures disappeared from their homes ahead of the police.

Each evening Hilda and I have the same discussion; we must take cover ourselves; that it will upset the children and disrupt their lives. We never get beyond discussion.

My father was, in fact, making arrangements – for drivers to take other people who were in hiding to Swaziland – but he put off the day when he and my mother would have to leave themselves.

They did agree that mom would leave home early each evening, sleep somewhere else, and only return in the morning.

I intend to do the same but am always too tired to actually do so.

The night of their arrests, my father writes:

I reach home dog-tired. I am half intending to find somewhere else to spend the night but find that Hilda is still at home. She, too, has decided to sleep out after the children have been put to bed.

But their plan was thwarted by the arrival of a colleague who had been tipped off to leave home ahead of the police. My mom gave up her safe place to him and had nowhere else to go. They were both exhausted by then and so both stayed at home. That same night they were arrested.

None of us went to school the following morning but hung about the house, not sure what would happen next. Later that morning, my uncle Harold arrived to discuss what arrangements would be made for us with Yvonne ‘Fuzzy’ Lewitton. The Lewittons were family friends who lived close by. Fuzzy was anxious to get home to make her own arrangements for her disrupted life and that of her children. Her husband, Archie, had been detained that night as well, and she’d not only had to find a way to manage his pharmacy in town but her own job as a psychology lecturer at the University of the Witwatersrand. She had yet to tell her nine-year-old daughter, Linda – a weekly boarder at a private school – of her father’s arrest. The couple’s son, Andrew, fourteen, was at home.

I didn’t want us children to be separated and sent to stay with friends or relatives. I knew that it would be better for all of us if we could stay at home together and was hoping that a way would be found for this to happen. I felt adult enough to be left in the house with the children. Unrealistically, I imagined that I could care for them with the assistance of our two helpers, Bessie and Claude.

We didn’t know how long our parents would be in detention and grown up as I was in some ways, I had no idea of finances or of running a household. I didn’t think about how the younger children would get to and from school and nursery, or how, even with Bessie and Claude, I could care for the four of us, and give enough love and attention to my brothers and sister. Keith, whom we all adored, was only three years old. He had rust-coloured hair and was cute and chubby. Patrick was eleven: he also had red hair and although he was very introverted, he and his gang of friends were always getting up to mischief. Then there was sweet, sunny Frances, who was nearly eight. At sixteen, I was far too young to care for three children.

I stood around while the adults discussed arrangements, unable to find a way to express my feelings. In any case, I wasn’t consulted. Although my father’s relatives were comfortably off, with large houses and staff, they lived in other suburbs and there would be practical problems getting us to and from school and friends if we moved in with them. The Lewittons lived three streets away from us, and we would still be near our schools and friends. It was finally decided that, for the time being, I would move to the Lewittons’ house with Pat and Keith, while Frances – who was on holiday with our aunt and cousins – would join us a few days later.

Three streets apart but very different houses. Our house – in the suburb of Observatory in Johannesburg, with its big houses set in large gardens – was spacious, with huge windows which let in ample sunlight. We had a lovely garden, with fruit trees and a pool. Theirs, in neighbouring Bellevue, was small and dark. The entrance served as the dining area. The kitchen opened onto a small concrete back yard. One of the two front rooms was the living room, while the other had been made into the main bedroom. There were two more bedrooms at the back of the house, one of which Andrew and Linda shared. It was always a mess of clothes, toys and books. It felt cramped and unattractive. None of us wanted to stay there.

I don’t remember how our parents’ disappearance was explained to little Keith. I also don’t recall how much Pat and Frances understood about what was happening or why our parents had been arrested. I do remember that we were all miserable about being uprooted but we kept quiet about it.

All around the country, there were hundreds of other children being farmed out to friends or relatives and having to adjust to one or both of their parents facing an open-ended period in prison without trial. It must have been hard for Fuzzy to take on four children, one of whom was only three years old.

We were all at different schools and distressed about our parents’ arrests. Fuzzy’s children were also upset by their father’s disappearance; she had a lot on her plate. I knew Fuzzy well and liked her. She and Archie often visited our home. She never spoke down to me or treated me as a child. But she wasn’t my mother and living at their house was a far cry from being at home.

While we were moving into the Lewittons’ home, my parents were being driven to Marshall Square, a large police station in the centre of Johannesburg, where they were processed, their money and watches confiscated and separated into male and female cells.

At Marshall Square, my dad found there were already fifteen others in the male cells. In his memoir, he writes:

Some – like Archie – are former communists who have long since dropped out of politics. Some have even changed their political orientation entirely. They are all disoriented and shocked to find themselves summarily jailed. What have they done to deserve this? They have had no part in contemporary politics. They cannot seriously be regarded as any sort of a threat to the State. The only possible explanation must be that the Security Services are still using lists, which are ten years out of date. In the evening, we are driven to the Fort to be locked up together with all those arrested earlier in the week.

Among the women detainees were also several who had long since left politics. My mom describes their first day:

Friday, 8 April continued

At last, at about 1 o’ clock, we were taken to waiting prison vans. We began to sing, we said goodbye to the men, who were taken to prison in another van, and were driven through the streets at breakneck speed.

People stopped and stared with surprise at the sight of white women in the inevitable kwela-kwela4 usually filled with silent Africans. Police cars cleared the way in front with sirens going, and an armoured car followed behind.

The detainees were driven to the Old Fort – an old prison next to the suburb of Hillbrow, now Constitution Hill. There they were called into the Matron’s office and processed.

The Fort was built by President Paul Kruger in 18935 to house white male prisoners. In 1910, a women’s jail was added in close proximity to the Fort. In 1960 the old buildings were overcrowded, and conditions were primitive and unhygienic – even in the white section. In the African section, conditions were barbaric. Shoeless and in ragged prison clothes, prisoners were crowded into filthy cells with no mattresses. Their toilet facilities were very basic, and their food was extremely poor. The Fort was mainly used to house awaiting-trial prisoners.

There were eighteen of us, so all this took a long, long time. We finally ignored the wardresses, to go and stand in a courtyard, where we saw Rica and Violet, arrested ten days before, leaning languidly through the bars of a cell. They looked so much at ease, their faces made up (we thought they would take away our lipsticks and cosmetics), Rica smoking with a long cigarette holder in her hand, that the sight of them allayed some of our fears … I didn’t want to think of my family, particularly Keith. Just to hear his name made me want to cry.

Both Rica Hodgson and Violet Weinberg were close friends and colleagues of my parents. Violet’s husband, Eli, was detained with the men, but Rica’s husband, Jack, had managed to escape to Swaziland before they could arrest him. Two other women had also been arrested ten days earlier, namely Philippa Levy – who was released after a few days – and Helen Joseph. Helen came from a conservative English home and had come to politics via the path of social welfare work.

When the new detainees arrived, they found the four women in a sunny corner of the exercise yard, where Rica, ever glamorous, was painting her nails. Helen remarked later that only Rica could be woken by the Special Branch at two in the morning and remember to bring her nail varnish.

It was a boost to see their friends, who were equally glad on one level to see the newcomers.

At the Fort there are 25 of us in the white male section. Other men and women, black and white are being held in other places, but we have no idea how many. Conditions are basic and uncomfortable. Once three felt sleeping mats are laid out on the floor, touching each other in cells designed for one, there is just room for our single chamber pot.

Dad’s prisoner property receipt.

For us children the first days away from home were difficult, too. Although I was in many ways a typical teenager and as self-centred as most girls are at that age, I did have a developed sense of responsibility for my younger siblings, especially for Keith who was thirteen years my junior and whom I regarded partly as ‘my’ baby.

I also felt somewhat involved in what my parents did. Together with my close friends, Barbara Harmel and Ilse Fischer (daughter of Molly and Bram), I belonged to a Saturday ‘club’ known as the Young Democrats, where the older children of politically active people learned about the many things that were going on in our country and the world. It made us feel part of what our parents believed in.

I wanted to protect my parents, too, from worrying about my siblings. At sixteen I was allowed to visit them in prison, something that made me feel like an adult. For the younger ones it was much harder. Patrick became withdrawn and silent. I didn’t know how to break through his shell, he hid his pain and was hard to comfort.

Frances was very upset when she returned from her holiday and found herself living at the Lewittons’ house. But at least both she and Pat understood – more or less – where our parents were. Keith was too young to grasp what had happened, and he didn’t want to leave the house. Our Aunt Jean arrived to take Keith to nursery school every morning – but he refused to go. In his little mind, if our parents came home while he was at school they would not know where he was.

Ivan and Lesley Schermbrucker, friends and colleagues of my parents, lived in the street behind us. They had two children roughly the same age as Pat and Frances, and Lesley, who was very fond of Keith, helped to look after him in the afternoons.

We hated the meals at the Lewittons, which were valiantly cooked and supplied by their long-time domestic helper, Muriel. Fuzzy was at work for most of the day and we were left to our own devices after school. It was very different to our home scenario. Although my mom worked, she was usually home by the time we returned from school in the afternoons and, unlike Fuzzy, she was very much a homemaker.

We just had to adjust and get on with it like all the other children of detainees. School and friends provided some normality for all of us. We never spoke to anyone about our miseries and if anyone had ventured to ask us how we were getting on, we would probably just have said, ‘Fine’.

On some days, we went home after school to see Bessie and Claude and to visit our dogs, Fluffy and Muffin, and our cat Tintin. I didn’t like going to the house under these circumstances: it felt empty and wrong but at the same time, I liked to spend time in my room with my own things.

While we were getting used to our changed lives, the women were adjusting to their new circumstances. Instead of cells, the women detainees were put into dormitories comprising two large rooms filled with beds.

The prison authorities were at a loss as to what to do with them. They had little or no experience with a large number of middle class, educated women who stood up for their rights. This was very different from the few white women prisoners they dealt with, the majority of whom were in for petty offences like drunkenness, prostitution or theft.

Most of the wardresses in charge of the women were very young. My mother said many of them were attractive girls but in a short space of time, their faces changed, becoming grim and hard as they shrieked abuse at the women prisoners. The yelling became a habit. They shouted not only at the prisoners but also at each other. The detainees speculated about what made them take such a job. At first the wardresses tended to be hostile to the women, but they were also very curious about them. In the end most of them became friendly.

Right from the start, the women protested about their detention and the conditions in prison.

Saturday, 9 April

We all had a horrible night. The mattresses were just hard lumps of coir, the discomfort of rough blankets, no sheets, and the bilious feeling left by forcing down a few mouthfuls of curried water and potatoes the previous night, left us bleary-eyed and headachy. In addition, many of us had arrived at the Fort after a nightmare ten days of tension and alarms that had become almost unbearable.

We were told to line up for the doctor, and angry and rebellious, we decided to make a fuss about everything

‘Are you fit?’ was his question to each of us in turn. And each of us replied, ‘Yes, we were fit when we came in, but we won’t be if we have to put up with these conditions for long.’

The doctor was balding and middle-aged, with the look of a man who either suffered from a nagging wife or continual indigestion. I told him that many of us were middle-aged women, at a difficult time of life, physically speaking, and felt we couldn’t easily adjust to the prison diet.

The doctor – first of several to tell us the same story – maintains that the prison diet is scientifically worked out to provide all the food-values needed. ‘No one has ever left the prison weighing less than when they came in.’ ‘That’s just the point,’ we say, ‘heaviness is not an indication of good diet or good health.’

He asks me to prepare a memorandum along the lines of which I have spoken to him and says he will pass it on to the authorities concerned. We regard this as our first victory and it proves to be the first of an endless succession of memos, petitions, requests and complaints that are put in writing and passed on – and out of our lives.

Matron raises her gorgeous, heavily painted eyebrows and is annoyed that we didn’t first bring some of our complaints to her.

We are told the Colonel (gaol supervisor) is arriving and we may appoint a deputation to lay our complaints before him. The deputation is Margaret Kalk (our food expert), Shulamith Muller (our lawyer), and Betty du Toit and myself (two who talk too much).

Colonel Le Roux is a khaki-looking, severe, lined, cold man. He starts by telling us we are all detainees and must conform to prison regulations – then he listens to our complaints:

1.That we were denied access to relatives;

2.Our children were left uncared for;

3.We had had no opportunity to delegate powers of attorney;

4.To attend to payment of rent;

5.And so on.

The Colonel began by saying he could say something very rude to us but wouldn’t. He then said it may be possible to see legal representatives, in which case these problems would be dealt with.

Margaret explained she had left two sons, both students, without money, when she and her husband were arrested.

Colonel: ‘You should have arranged these things a year ago.’

Margaret: ‘But I haven’t dabbled in politics for about fifteen years, how was I to know?’

Colonel: ‘Do you mean to tell me you have never dabbled in politics?’

Margaret: ‘No, but I have had nothing to do with any political parties or activities for such a long time, that I had no inkling that I would ever be involved in such a situation.’

The Colonel then abruptly implied that it was our own fault that we were here, and therefore we could expect nothing.

Margaret was not the only person who had long left politics but had now been detained. Several of the other detainees, both men and women, had only ever been marginally associated with anti-government politics or were no longer politically active and were shocked to find themselves suddenly in prison – and with a number of communists, to boot. And initially, they thought the mistake would be rectified and they would be released.

Freda had arrived at Marshall Square immaculately dressed, with earrings and high-heeled shoes, but proved to have failed to pack any change of clothing. ‘Why didn’t you bring anything?’ we asked her. ‘I thought it was all a ghastly mistake,’ she replied.

Before long, the women obtained certain concessions from the Colonel. They were allowed recreation time in the yard outside their cells and some games would be brought in – but no books, of course.

Money could be deposited for them, and the Colonel said he would look into the matter of writing materials and paper, and their jewellery.

They asked again about the food and were told they were receiving the proper diet as laid down in prison regulations for whites.

Margaret: ‘Do you mean to say there are different diets for different racial groups?’

The Colonel: ‘You are making a political question out of this.’

Apartheid affected every part of life, even in the diets of prisoners in South Africa. Prisoners were classified by racial groups – whites, coloureds, Indians and ‘natives’. The black prisoners were given mainly maize porridge (mealie meal) and beans, with meat only once or twice a week. The Indians and coloureds got more rice and more meat than the black prisoners, while the white prisoners were given soups and stews. Bread was not considered part of a black diet.

One day, while the women were out in the yard, an African prisoner walked by and dropped a little ball of paper close by. It contained a note from Bertha Mashaba and Violet, two of the black women detainees at the Fort, complaining about their food and included a sample – some horrible-looking black mealies.

Acutely aware that the conditions of their black women colleagues were far worse than their own, the women managed to get a wardress to send the black detainees some of their bread and meat and were allowed to transfer some of their money into their accounts.

They also managed to obtain the release of one of the black women, Georgina Mofutsanyana, who was mistaken for her husband’s first wife.

What a day! To end it all, the girls in the second cell saw a metal plate above Freda’s bed, and she was convinced it was a microphone. Sheila climbed on Freda’s shoulders – Freda standing on the bed – and with a great effort they managed to pull at the plate. Down came a cloud of black soot, all over them. There was a great deal of hilarious laughter.

There was camaraderie among the women, who found comfort in being together. As a group of highly vocal, middle class political activists, being together gave them the strength to complain and make a nuisance of themselves to the authorities.

All our watches have been taken away. The time of day is to be ascertained only by the routine sounds of routine days.

Woman prisoner cleaning floor.

‘When they were taken out into the yard to exercise or out of their cells for any other reason, the wardresses would shout: ‘Maak oop die hek, hier kom die Noord Regulasies’ (‘Open the gate, here come the Emergency Regulations’). Soon they were known all over the prison as the ‘Emergency Regulations’.

Meanwhile, the men were also grappling with the dreadful food

and poor conditions.

During the day we have access to a tiny enclosed yard on a lower floor where the light filters in dimly through a dusty steel mesh roof. In one corner is a cesspit where chamber pots are emptied each morning and food bowls scrubbed.

Poor-quality food arrives from a distant kitchen in battered steel bowls, which are laid out in the stair hall and left to congeal before they reach us. Ronnie Press, the scientist amongst us, makes a trawl through the lunchtime stew and mounts his catch of weevils, grubs and other creepy-crawlies on white card, like a museum exhibit. He presents it to the Prison Commandant on his next inspection. It’s received without comment and taken away.

Before long, we have an outbreak of diarrhoea. The prison doctor looks at our tongues from a safe distance and hands out sulpha tablets. As the outbreak becomes an epidemic, dispensing pills becomes too onerous for him and he hands a wholesale supply of sulpha tablets to our two pharmacists – Archie Lewitton and Jock Isaacowitz – to dispense as they see fit.

Around 4 pm the steel grille gates between our cells and the corridor are locked for the night. Lights go off around ten.

On their second day in prison, the routine of the male detainees was interrupted by unusual panic.

It’s about 2 pm. It should be quiet with warders off having lunch. Suddenly there is the noise of men shouting and hurrying about, doors and gates slamming. It cannot be an escape – there are no alarms, though we can hear vehicle sirens in the streets beyond the walls, and the wail of emergency vehicles. The warders seem unusually hostile. Routine is the source not only of our sense of time but of all sense of normality. Rumour spreads like wildfire. It is said that Verwoerd has been shot. It would be dismissed as false were it not the turmoil around us. And, even more scary, could the killer be one of OUR people? If so, it has terrifying implications for all of us.

Hours later, the rumours and gossip solidify into facts. Verwoerd has been shot while on a visit to the Easter Show6. He has been rushed off to hospital – no one knows whether he is alive or dead – and not many of us care.

We find out only later that the shot was fired at point-blank range by a white dairy farmer with a grievance. The shot has passed through Verwoerd’s cheek but has not deprived him of the ability to speak.

Prime Minister Dr Hendrik Verwoerd, known to have been a sympathiser with the Nazis during the war, was known as the chief architect of apartheid and enforced it with a rigid brutality that caused enormous suffering. Although he survived this attempt on his life, on 6 September 1966 he was assassinated by the parliamentary messenger Dimitri Tsafendas, a Portuguese national of Greek descent, who stabbed him in parliament.

I regard him as not just bad but mad; and his apartheid to be the most inhuman attempt at human engineering since Hitler’s ‘Final Solution’7.

Looking back at that time, with the knowledge of what came only a year or two later, it seems a benign and lenient way to detain political prisoners. These conditions lasted only during this first State of Emergency. It wasn’t long before far harsher treatment was given to political prisoners, when torture and solitary confinement were introduced. After 1960, political prisoners were denied any of the comforts of the Emergency detainees.

Nevertheless, detention wasn’t a kind of enforced holiday camp. This was prison. Conditions at the Fort were cramped and unhygienic. The male political detainees were housed in a double-storey block of cells that led onto a hall, which doubled as a dining room. Leading off from this was a concrete exercise yard with high walls. On arrival the cells were indescribably dirty, containing a straw mattress, a few blankets and a sanitation bucket.

After protests and the diarrhoea outbreak, both the living conditions and the food improved to some extent. To the warders, the men were an enigma: clean, tidy and well-educated, and utterly unlike the awaiting-trial prisoners who were their usual charges.

However bad conditions were for the white detainees, they were far worse for the black and other detainees. Worst of all were the conditions of convicted prisoners.

Sunday, 10 April

Lights out at eight leaves one plenty of time for lying in bed and thinking. Whether you fall asleep early, in which case you wake at 3 or 4 am and can lie and think until the morning bell goes at 6:30 am, or else you do it at night before getting to sleep. Others have young children, too, but we do not discuss it, we each nurse our own sorrows. We all have our own individual worries. To me, Molly’s (Fischer) is the worst of all.

Memorandum of conditions of hygiene and medical attention.

The Fischers youngest child, Paul, suffered from cystic fibrosis and was chronically unwell, needing a lot of care.

As soon as I think of Keith or Frances, or someone mentions them, tears rush up. Frances was due back from her holiday today. Who met her and told her? How will poor Fuzzy cope with shop, home and all the children? Will relatives assist financially? And how long will it last?

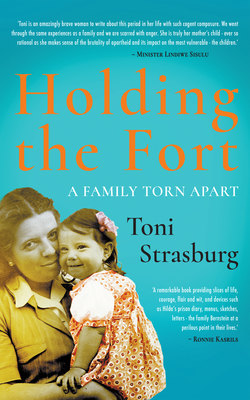

Cover image of my mother’s gaol poetry collection.