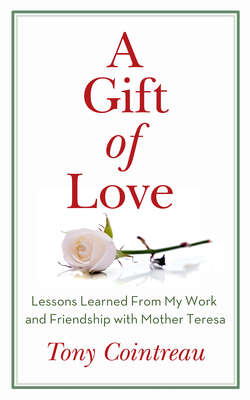

Читать книгу A Gift of Love - Tony Cointreau - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 2 Listening “And all I did was listen.”

ОглавлениеOne of the first things Mother Teresa ever told me was, “Tony, if you’ll just listen, you’ll find that there is something beautiful about each of these men.” And, before long, I could see it.

I loved them all.

And I lost them all.

But through the years I learnt my lessons as I went along—both by watching the nuns and other volunteers and by following my own instincts. Each situation (and there were dozens every day) was as different and unique as the men were.

At first all I tried to do was gain the men’s trust by showing them that I was sincere about my work. This meant mopping floors, washing stairs on my hands and knees, cooking (not my greatest talent), answering the phone or the door, changing diapers on grown men, taking our patients to the clinics and waiting for hours in emergency rooms for doctors who were helpless to do much, if anything, for people with AIDS. In essence, it meant proving to one and all that I was happy to do the most menial of tasks with a smile and a willingness at any time to drop my work and just listen to a young man who was anxious to unburden himself to a friend.

From the beginning the Sisters had explained that although my duties would be whatever came up at any given moment, the most important work of all would be to listen to the patients—not only to what they said but also to the things that some of them sometimes found difficult to articulate.

A young man called Robert, who (I was told by another volunteer) had been in a prison “with the really bad boys,” was having a difficult time keeping up the “tough guy” image he felt he had to portray.

Although Robert hated to show his vulnerability, I suspected that he had been conditioned (not unlike myself) never to give in to any show of weakness in front of others. He did, however, often like to complain, so I just listened to the good and the bad. I knew I had made some headway the day he confided to me, “I hope I pass the summer, and if I pass the summer, then I can go in peace.”

Later that afternoon, as I was leaving, he leaned over the banister and called down, “Tony!”

I looked up and said, “Yes, Robert.”

For a moment he seemed at a loss for words, and then stammered, “Your collar’s crooked.”

The words Robert used were immaterial—I knew instinctively that that was the only way Robert was able to express, “Thanks for being here and listening.”

I once tried to make a list of the things we respond to from the day we are born, and one of the first ways we bond with a parental figure is by communicating our feelings through tears or laughter. Mother and father then have to listen carefully to how we make ourselves understood so they can react accordingly. A loving parent usually ends up able to interpret each nuance in their child’s sounds and demeanor.

Later, when we learn to express ourselves with words, we have a deep need to share each new experience with someone who cares. It may be a parent, a schoolteacher, a grandparent, a friend, or all of the above. But one person’s close attention to our joys, our sorrows and our endless questions are a vital part of our growth—especially while every little happening in our lives is still the most exciting thing in the world to us.

As we reach adolescence, it becomes even more confusing if there is no one there for us to relate our concerns to about the emotional and physical changes taking place. How many troubled teenagers say that all they really miss is a parent or mentor to spend time with—someone who will take the time to listen.

Loneliness and fear take root early on in our lives when we feel we have no one to talk to. And in the twenty-first century, when both parents often have full-time careers, it becomes increasingly difficult for a mother and father to find the time to listen to what is happening in their children’s lives. Emotional issues are usually the first to be put on the back burner and are considered “normal” for that age. Because parents often don’t have the time to spare, they forget the immediacy of the trials of their own youth. They figure these are minor problems that can be dealt with at a later time— a time that sometimes doesn’t come before enormous damage has already been done.

In my grandparents’ day, before the world was filled with high technology, families lived in a home where the children were usually born and where there was always a place for the older generation to live out their lives. The cycle of birth and death was not a mystery to young people who were active participants in all aspects of family life.

Today women cannot be faulted for choosing the safer option of a hospital birth for their child. Neither can they be faulted for no longer being able to care for an elderly family member in their home. But the sad part of all this is that it has helped create a new world where children are not taught the natural progressions of life. Now the aging process of a beloved grandparent is often, at best, kept at a distance while a staff of strangers takes care of them in what is now called “assisted living.” In these facilities all responsibility is taken off the family’s shoulders as the necessary level of care is upgraded with time.

This situation enables the next generation to ignore the final stages of life that the older person goes through and does not give the younger ones the benefit of the wisdom, love, or connection to those responsible for their heritage. And so the charade continues, while we permit ourselves to hide our heads in the sand and pretend that the impersonal care and feeding of those who raised us are adequate substitutes for our love.

The tragedy of abandonment of the ones who have nurtured us, who desperately need our love at the end of their lives, was overwhelmingly shown to me when I went to an assisted living home in New York City called Atria, where my old nurse Lucy, who had cared for my brother and me when we were born, was living.

When I arrived, I was told that Lucy was at a doctor’s appointment with her aide, so I went into a comfortable little sitting room to wait for them to come home.

When I sat down, I noticed an elderly lady in a wheelchair talking on the phone with her son, pleading with him to come visit her. I could tell she was speaking in the most diplomatic way possible, so as not to anger him.

At the end of their conversation, I nearly fell out of my chair when I heard her say, in the sweetest possible way, “But, darling, you only live a block away.”

In no way am I condemning anyone for the way their lives are dictated in this new age we live in. But it is no excuse not to wake up and make your presence known to the millions of elderly or dying people waiting in vain day after day for the sound of a familiar voice.

My great-grandmother, Louisa Cointreau, was a remarkable woman who had been decorated by the French government for her work creating hospitals and taking care of wounded soldiers during World War I. By the time I met her in 1947, when I was six years old, at her château in the Loire Valley where my parents and my brother and I spent most of our summers, she was senile and remembered nothing from one moment to the next. Nevertheless, she lived at home under the care of her family and participated in all their activities.

In spite of her senility she remembered everything that had happened years before, and spent hours with me poring over old photograph albums and telling me who each person was. I only wish we had had more time together and that I had known her before she became senile. Today I realize that my having listened to her relate her history was something that gave her great joy, and, for my part, something I will always treasure. Of course, she never had any idea who my brother and I were, and every few minutes would ask anyone passing by, “Who are those two little American boys?”

Not only was it no bother to tell her periodically that we were her great-grandchildren, but it always pleased me that the thought of our being related made her so happy.

Grandmère Louisa, as I called her, died peacefully in her own bed at home in 1952, with her family and friends at her side.

But I have found that even when human beings have been forced to spend their whole lives in a state of lonely desperation, at the end, the door to their emotions is always ready to be opened. Although it may be only days or even hours before death that they find that loving ear, the deafening quiet of a lifetime can be erased forever in those last moments. It is never too late to make the connection, especially when it is a connection born of love.

From my first day at Gift of Love I found the men anxious to share their varied and often tragic stories with me, and as the years went by, I thought that nothing could shock or surprise me anymore. But every time I started to feel that I had heard or seen it all, someone would come along and knock me off my pedestal of complacency and teach me one more lesson about the complexity of the human condition and the importance of honoring each of my friends’ unique stories.

One of these men was Abraham, one of the sweetest human beings who ever walked into Gift of Love. He soon managed to open my eyes to a possibility in the range of suffering that I had not yet contemplated.

Abraham had come to us in the last stages of AIDS, with a prognosis of days or a few weeks at most to live. The doctors had been preparing for an operation to attempt to save his sight, but now they told us that it was too late to even try. Shortly after he received the news, one of the Sisters asked me to go up to his room and talk with him.

The moment I walked into his room, he brought me up to date on the discouraging prognosis. When I asked him how he felt about it, he said, “I’m at peace. I’m not afraid of dying but I don’t want to suffer.” I told him that the greatest fear we all had was of suffering.

Then I noticed that the beautiful long black hair that I had seen before had now been cut short. As soon as I mentioned that he had cut his hair, his peaceful demeanor began to crumble and he started to cry.

“Oh, Tony, you don’t know. You just don’t know. Please don’t tell anyone—nobody knows—but when I became sick I was in the last stages of gender reassignment. My dream was to become a woman. Now that dream can never be. It’s too late. I’ve become too sick and know I won’t even be able to die the way I wanted— as a woman.”

Every day after that I went into his room and every day he always had the sweetest smile on his face. Sometimes we would just sit silently together. Words were no longer necessary. We had created a bond of love and understanding.

And the only thing that had made him cry was when he knew that he would not die as a woman. What I believe helped make it bearable was that he could safely share it with another human being who would never judge him.

I always considered it a gift when a terminally ill man felt comfortable enough to open his heart and his life to me, a virtual stranger, and allow me to share in the preparation for his final journey. What I didn’t realize at first was that in confiding their deepest human secrets they were releasing many layers of confusion and hurt, which then allowed them to find a peace that had eluded them for a lifetime.

None of us has to be a genius to make a difference in someone’s life or death. It takes no great intellect or training. It’s only a question of sincere listening and genuine caring. This can be the final gift from the person who knows you best in the world, or from a total stranger.

One afternoon I was alone doing some boring task in the kitchen (peeling potatoes seemed to be one of my specialties) when a new patient named Joe came downstairs to the kitchen door and asked, “Can I talk to you?”

I said, “Sure, Joe. Just let me take off my apron and we can sit in the little office by the front door.”

When my earthly eyes looked at Joe I saw a sickly, long-time drug addict with most of his teeth missing. It would have been hard for me to guess his age.

He took a seat and said, “Tony, the doctor told me that besides having AIDS, my body is filled with cancer and I don’t have long to live.

“I’ve been a drug addict since the age of fifteen. Now I’m thirty-seven going on ninety-seven, and I’m probably going to die soon. All the friends I ever had are dead from drugs or AIDS. There’s no one left.”

He went on to say, “I loved my mother very much, but I’m glad she’s dead too and did not have to live to see me in this condition.

“Although I was brought up and lived my whole life on the lower East side of Manhattan in some of the scariest parts of the city—places you would never want to bring up a child—I’m grateful that God has been good to me and has allowed me to survive longer than anybody I knew.

“Believe me, everything that has happened to me, I brought upon myself. I’ve spent a good part of my life in jail but I’m still in there pitching. I’m not giving up.”

I listened quietly while Joe recounted the hardships of his life, the years of addiction, the years in jail, the pain of losing everyone around him, and even the feeling of uselessness of his life.

After Joe finished relating his story, he seemed almost lighthearted. Somehow he looked younger to me, as though a burden had been lifted from his frail shoulders.

Before getting up to go back upstairs, he held onto my hand and said, “Thank you. Thank you. I love you, man. I don’t know you but I love you, man. I know you’ve got it right here.”

And he put his hand on his heart.

And all I did was listen.