Читать книгу Time Bring About a Change - Tony J.D. Carr - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter Two Bluster

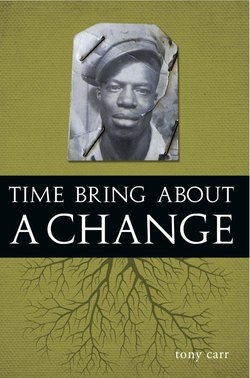

ОглавлениеMy mother’s father, Arnett Henry Sr.—whom we all called by his nickname, “Bluster”—grew up in Mississippi in a very poor family. My grandmother would joke that when she was a child, she and her family would pass by the Henry place on their way to church on Sunday mornings, and they would see Bluster and his siblings running around their yard naked. The children would run and hide in the bushes until the horse and buggy passed by. It wasn’t that they didn’t know any better; they simply didn’t have many clothes, and what outfits they did own were kept nice in a closet, not used at playtime when they could be soiled or torn.

My grandfather never denied the story. On the contrary, he himself often told stories about how poor he was growing up. Once he was reading a magazine story about the famous basketball player Wilt Chamberlain. The magazine featured pictures of Wilt’s fabulous mansion, and it was reported that in Wilt’s bedroom he could push a button and the ceiling would open up to the sky. Bluster was unimpressed. “Shoot,” he commented, “when I was a little boy I could see the stars through my ceiling too, but we had holes in the roof; we didn’t need a button to push.”

Bluster was a religious man and often shared life stories that had a meaningful message. He often talked of life during the Jim Crow era, the time when all over the South, racist legislation known as “Jim Crow” laws kept blacks separate from whites. While these laws were in effect, from the late 1800s to the late 1960s, blacks were forbidden to use the same restaurants, bathrooms, and drinking fountains as whites. They had to occupy separate railroad cars and sit on seats at the back of the bus. They also faced restrictions in employment and voter rights, to name just a few.

Bluster grew up when things were separate but definitely not equal. He was blessed to have gotten a truck-driving job, making deliveries overnight and into the early hours of the morning in the early 1940s. Bluster said that often he would get hungry while driving and wanted to stop for something to eat, but he had to be very careful because stopping at the wrong locations could cost him his life. He would look for colored-owned restaurants or take a chance at a white establishment that might serve colored people in the rear of the restaurant. Bluster said “there was many a night” he just kept driving and went hungry because it was not safe to stop in certain towns or restaurants. He was always delighted when he found a colored-owned establishment.

Until the day he died in 1988, Bluster always spoke to white people with exaggerated politeness, addressing them as Mr. or Mrs. and saying “yes, sir” and “yes, ma’am,” no matter what their age. This bothered me when I reached high school, and one day I built up enough confidence to challenge him on these mannerisms. I had always viewed Bluster as a very strong man, but I felt he displayed weakness when bowing down to white people.

“Bluster,” I said, “Why do you address whites as sirs and ma’ams? Times have changed! It’s the ’70s now. You don’t have to do that anymore.” I then got cocky and said, “If I had grown up during your era, they would have had to kill me, because I never would have bowed down to nobody.”

Bluster sat me down and explained a few things. He said that all his life, and especially during his time of driving trucks, he had to do or say whatever it took to get a paycheck. Even though in his heart he knew he was equal to them, he had been conditioned during his young years to take an inferior role to white people in order to survive in a world where whites held all the power. He took the dehumanizing treatment for one reason and one reason only—he had four little children who depended on him, and he loved his family enough to sacrifice anything for them—even his pride. “There is nothing greater than the love of Christ and the love you have for your family,” he told me.

Bluster was the greatest grandfather I could ever have had. He was diagnosed with cancer in 1988 and given six months to live. When he told me about his diagnosis, he said, “Boy, I’m not scared to die, but what I will miss is that I won’t get to see my family anymore.” A month later, he died. We miss Bluster.