Читать книгу Liverpool - Tony Lane - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

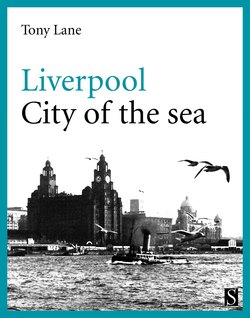

1 CITY OF THE SEA

ОглавлениеIf New York is the Empire State Building and Paris the Eiffel Tower, Liverpool is the Royal Liver Building. Although attacked by some architectural critics for its vulgarity – ‘swagger though coarse’, says Pevsner – painters, poster artists and television producers needing an instantly recognisable image of Liverpool always have the building somewhere in frame.6

When the Liver Building was opened in 1910 its clock mechanisms were boastfully presented as being the largest of their kind. By way of underlining such a trivial fact, the Royal Liver directors ate dinner off one of the clockfaces before it was put in place. That flamboyant gesture was of a piece with the times and the assertiveness that was even then so characteristically Liverpool.

The city was at its peak in 1910. Victoria, only recently dead, had not long been translated from mere monarch to Empress. In Liverpool, especially, the promotion must have seemed right. Red-ensigned merchant ships carried half of the world’s entire water-borne international trade and the most potently famous ships of British mercantile power, the Cunard and White Star liners, were operated from grandiose head offices on the Liverpool waterfront. Liverpool was the western gateway to the world.7

So many and so large were the fleets of passenger and cargo liners crewed by Liverpudlians, swarmed over and serviced by tens of thousands of other citizens, that the scale and intensity of ocean-going and coastal traffic made Liverpool a city-port like none ever seen before. A local journalist and politician said in the 1920s that the Pierhead, where the Liver Building stands, was a ‘threshold to the ends of the earth’.8 A permanent reminder of the truth of that statement were the huge, verdigrised cormorants (reclassified locally as ‘Liver birds’) atop the Liver Building’s twin cupolas, their wings outstretched to the Atlantic winds.

Calling at Liverpool in 1770 during his tour of some of the northern counties, Arthur Young said little of the city except that its glory was ‘the docks for the shipping, which are much superior to any mercantile ones in Britain’.9 Remarks to that effect were common then and continued to be so in the century that followed. Liverpool’s people became accustomed to thinking of themselves as belonging to a city with a place in the world. Horizons were seldom lower than that. Never down to the region, and unthinkably not to the south-west corner of Lancashire.

The shipowners, merchants and bankers who epitomised Liverpool wealth were global operators who regularly needed to turn their backs on Lancashire and look outward to the countries bordering the Atlantic, Pacific and the Indian Oceans. Liverpool’s seafarers, who brought the world home with them at the end of a voyage and stayed but a short time before embarking upon another, were no less cosmopolitan. Writing lyrically, but none the less accurately, Dixon Scott said of the port in 1907 that it was

the city’s raison d’être, the chief orderer and distributor of her people’s vocations; and in that way ... interweaves class with class, provides merchant, clerk, seamen, and dock-labourers with a common unifying interest.10

Eighteenth- and nineteenth-century visitors were naturally impressed by the volume and tempo of shipping movements and cargo-handling, but what unfailingly overawed them was the engineering coup involved in impounding almost one-third of the breadth of the river to create a tideless waterway. The long line of the river wall enclosing the docks on the Liverpool side of the Mersey once marked the limit of low tide. Herman Melville was a typical admirer. Arriving in Liverpool on his first seafaring voyage in 1839, Melville began with slighting remarks on New York’s port facilities and then compared Liverpool’s dock with the Pyramids and the Great Wall of China. And if this now sounds extravagant, it was a commonplace comparison of its time.

Fifty years later Ramsay Muir, the University’s professor of modern history, was no less impressed:

For seven miles and a quarter, on the Lancashire side of the river alone, the

monumental granite, quarried from the [Mersey Docks and Harbour] Board’s own quarries in Scotland, fronts the river in a vast sea wall as solid and enduring as the Pyramids ... Nor is this all. Immense ugly hoppers, with groanings and clankings, are perpetually at labour scooping out the channels of the estuary ... To a traveller with any imagination few spectacles present a more entrancing interest than that of these busy docks, crowded with the shipping of every nation, echoing to every tongue that is spoken on the seas, their wharves littered with strange commodities brought from all the shores of the oceans. It is here, beside the docks, that the citizen of Liverpool can best feel the opulent romance of his city.11

River activity sent many writers reaching for their pens. Another American literary figure, Nathaniel Hawthorne, was installed as the United States’ Consul in Liverpool in the 1840s. Living on the Birkenhead side of the river, he wrote in his diary that the

parlour window has given us a pretty good idea of the nautical business of Liverpool; the constant objects being the little black steamers, puffing unquietly along ... sometimes towing a long string of boats from Runcorn or otherwhere up the river, laden with goods; – and sometimes gallanting in or out a tall ship ... Now and then, after a blow at sea, a vessel comes in with her masts broken short off in the midst, and marks of rough handling about the hull. Once a week comes a Cunard steamer, with its red funnel pipe whitened by the salt spray; and firing off some cannon to announce her arrival, she moors to a large iron buoy in the middle of the river ... Immediately comes puffing towards her a little mail-steamer, to take away her mail-bags, and such of the passengers as choose to land; and for several hours afterwards, the Cunarder lies with smoke and steam coming out of her, as if she were smoking her pipe after some toilsome passage across the Atlantic.12

Thirty years later the Reverend Francis Kilvert, better known now than then, wrote in his diary that he had been to Liverpool’s Exchange:

one of the finest buildings of the kind in the world, and passing upstairs into the gallery and leaning upon the broad marble ledge we looked down upon a crowd of merchants and brokers swarming and humming like a hive of bees on the floor of the vast area below.13

The next day Kilvert took to the river:

The Mersey was gay and almost crowded with vessels of all sorts moving up and down the river, ships, barques, brigs, brigantines, schooners, cutters, colliers, tugs, steamboats, lighters, ‘flats’, everything from the huge emigrant liner steamship with four masts to the tiny sailing and rowing boats. From the river one sees to advantage the miles of dock which line the Mersey side, and the forests of masts which crowd the quays.14

Another clergyman, arriving in Liverpool from New York in the 1870s and writing for a New York newspaper, thought the city could be ‘aptly termed the “Chicago of England” [being] without doubt, essentially modern, and its rise and progress is something wonderful’.15 In the docks the Reverend Bell found

a long vista of vessels alongside the quay, lashed together with planks, reaching far ahead. There multitudes of goods are shipped – all kinds of hardware, railway supplies, iron in all shapes, of all kinds and sizes, sheet, wire, bar, spring, etc.; bales, boxes, casks, wines, spirits, ales, for India, Madagascar, Asia, Persia, the Continent and America.16

Major additions to the dock system appeared always as extensions of Liverpool’s grandeur, as opportunities to reassert the role of the city as a port and trading centre. Of global importance. When the Gladstone Dock was opened in 1927, F. C. Bowering, Lord Mayor, shipowner and a major force in world-wide marine insurance, reminded readers that Liverpool was still the world’s pre-eminent liner port and thought it appropriate also to remind the ‘rest of the world’ that,

Liverpool was called into being, not as a terminus for ocean tourist traffic, but as a junction for the landing, embarkation and storage of the vast wealth exchanged between the North and Midlands of England and the overseas world.17

No exaggeration was involved when another writer in the special supplement of the local daily newspaper said, ‘Worldwide interest is aroused by the completion and opening of the greatest dock which the world has ever known.’18

The world role or claims to size measured on a global scale were a recurring feature of articles written about one or another of Liverpool’s firms in the local press which was not then, nor subsequently, parochial. The Journal of Commerce was the more important of the two national daily shipping papers and far superior to the London-published Lloyd’s List. The Liverpool Daily Post was one of Britain’s great Liberal newspapers, if obviously inferior to the Manchester Guardian.

The constant juxtaposition of Liverpool and the world was not made extravagantly. It was presented quietly and confidently. Running through a list of the commodities imported through Liverpool, the chairman of the Liverpool Steamship Owners’ Association, ends by saying: ‘Almost all the world pours in its tribute.’19 Another shipowner points out that the frequency of sailings from Liverpool to Calcutta is ‘not excelled in any other long-distance trade in the world’.20 An advertisement for the Cotton Exchange accurately presents it as simply ‘THE WORLD’S GREATEST COTTON MARKET’.21 In like vein, the Stanley Dock tobacco warehouse is ‘the largest and most up-to-date in the world’; the Liverpool Grain Storage and Transit Company is ‘one of the leading grain handling concerns of the world’.22 Waring and Gillows, meanwhile, have so ‘exquisitely furnished and equipped’ Liverpool’s passenger liners that the city’s fame ‘as a centre for the manufacture of the highest class of furniture has spread all over the civilised world’.23 The city’s merchants have also been busy, tapping

huge consignments of cotton, corn, raw sugar, provisions, oil-bearing seeds, timber, fruit from over the seven seas of the world to the port of Liverpool.24

These cargoes and the ships carrying them were insured in Liverpool, making it one of the world’s greatest insurance centres.25 Surveying all these activities in 1927, the general manager of the Bank of Liverpool and Martins, said:

It is fitting that reference should be made to a characteristic of Liverpool which impresses a newcomer. Expressed briefly, the cosmopolitan outlook and worldwide interests which exist make it the least parochial of our cities, and Liverpool may well be proud of her commanding position.26

Novelists, poets and memoirists writing of their Liverpool connections place port, river, ships, merchants, shipowners and seafarers so firmly in the foreground that other activity appears secondary or absent altogether. As if to prove a once popular contention that Lime Street led to all parts of the Empire, there stands over the main entrance of the old Lewis’s department store a large bronze figure by Sir Jacob Epstein: poised like Ulysses on a ship’s prow, a muscular nude looks purposefully seaward.

John Brophy’s novel City of Departures is set in Liverpool at the end of the Second World War. His protagonist Charles Thorneycroft is returning to the city after artistic success in the metropolis and reflecting, that had he stayed in his native city, he would have become ‘a “local painter”, deriving most of his income from formal portraits of aldermen and shipowners and cotton-brokers’.27 Describing his city, Thorneycroft recalls that there was hardly ever a day without wind and that that, too, spoke of the sea and the port.

The city air was fresh, it blew perpetually, strong or mild, off the sea and the river, and channelled its gusty way through every street. It ought to be a healthy air, and it had the tang of health, the odour of tidal salt water, edged with smells from mud flats and sandhills and shores strewn with seaweed. But it was not healthy. It was laden with smoke and soot and grease, and with smells from tanneries, breweries, oil-cake factories, margarine factories, smells from the engine-rooms of ships, from dockyards, from thousands of warehouses where every sort of cargo was stored.28

Walking through the city streets, noticing the grime and dirt, the dinginess and the unrepaired bomb damage, Thorneycroft is depressed by the contrast between what he sees and his boyhood memories of a proud, thriving place. But once on the river he rediscovers Liverpool’s urgency.

Here where the ships sailed in and unloaded, loaded again and sailed out once more to all the oceans of the world, here was visible all around him a continuing magnificence. Here was no sign of lethargy or despondent regrets for the prosperities of the past. Here Liverpool was laying claim with a brawny fist to its own important place in the world.29

Far more contemporary, saturated with recent memory, is Matt Simpson’s anthology of poems relating the benchmarks of childhood and adolescence in a waterfront district.30

Leaving the city to go to college, Matt Simpson says he was

... the sailor’s son who never put to sea.

I left the city like

the Cunard liners and returned

to find their red and black

familiar funnels gone from gaps

between the houses where I’d lived,

those girls become as vulgar as

tattoos along my father’s arms.31

And he recalls the streets of childhood:

Salt winds keep these ocean-minded streets

voyaging. There are men here who, landlubbered

(wedded, winded, ulcered out), still walk as if

steel decks were rolling underfoot; riggers

and donkeymen, dockhands and chandlers,

shipwrights and scalers, who service ships

with something of love’s habits, insisting on

manhood and sweet memories.

Look in one bedroom. On

the glass-topped dressing table stood

a carved war-painted coconut Aztec head –

to me, memento mori, shrunken thing,

who watched death dredge this bed.

And yet for years it was a trophy,

souvenir of all the thousand miles

of furrowed brine, of fragrant isles.32

Cheek-by-jowl with Liverpool’s heroic feats of dock engineering, world-scale organisations of commerce and finance, and the sights and sounds of ships and cargoes there were less reputable institutions. As much a part of Liverpool as the respectability of business and other productive employments was the sailors’ Liverpool, discreetly evoked here by a young ship’s doctor in 1911:

The sailor is the real king of Liverpool. Everybody in Liverpool loves the sailor, and is only too anxious to show him how to have a good time and spend his money while he is ashore; and it is he is the great man there till he has spent it.33

The young Dr Abraham, about to embark on his first voyage, was carefully echoing a rowdier rhetoric of the second half of the nineteenth century – that merchant seamen were essentially innocent, noble savages, preyed upon by a vicious class of semi-criminals when ashore. So apparently effective were these beliefs that in Liverpool, as in other ports around the world, Sailors’ Homes were being built from the 1830s onwards to provide sinless shelter. The oratory that might be employed to finance the construction of these Homes could not often have been more eloquent than that of the Reverend Hugh McNeile at an inaugural meeting in Liverpool in 1844:

If every sea is whitened with our canvas – every foreign harbour crowded with our ships – if from every country, and from every clime, there flows into our native land a full tide of all that ministers to the comforts, the conveniences, and the embellishments of life, to the materials of our productive industry, and the sinews of our national strength – it is to the energy and enterprise of our seamen that we are indebted for these blessings ... And what is the return we have made? What is the social and moral condition of that class to who we acknowledge these obligations? ... They return, indeed, from distant scenes and barbarous climes to the bosom of their countrymen, but they return to be plundered and pillaged, seduced and betrayed, by sharks and harpies ... they are so helpless and so confiding ... they have had so little of the habit or the means of becoming provident, that they dissipate their hard- earned wages in a few days and are obliged to engage in any service, or embark on any voyage, by which they may extricate themselves.34

Charles Dickens was visiting Liverpool at this time, ‘keeping watch on Poor Mercantile Jack’ and, as if not to be outdone by the Reverend McNeile, records a seaman

with his hair blown all manner of wild ways, rather crazedly taking leave of his plunderers. All the rigging in the docks was shrill in the wind, and every little steamer coming and going across the Mersey was sharp in its blowing off, and every buoy in the river bobbed spitefully up and down, as if there were a general taunting chorus of ‘Come along, Poor Mercantile Jack! Ill- lodged, ill-fed, ill-used, focussed, entrapped, anticipated, cleaned out. Come along, Poor Mercantile Jack, and be tempest-tossed till you are drowned!’35

Dickens had visited Liverpool, he says, to join the police for a night and to be shown ‘the various unlawful traps which are set every night for Jack’. Melville also found ample provocation to moral outrage:

of all seaports in the world, Liverpool, perhaps, most abounds in all the variety of land-sharks, land-rats, and other vermin, which make the hapless mariner their prey. In the shape of landlords, bar-keepers, clothiers, crimps, and boarding-house loungers, the land-sharks devour him, limb by limb.36

Although the Sailors’ Home was soon built, the intention of undermining the disreputable part of Liverpool’s economy was never realised. Three decades later, in 1879, the Liberal Review was saying that it was an everyday thing ‘to find seamen, the day after their arrival in port, lying about the streets ... almost naked, and in a stupefied state’.37 And a full century after Dickens, McNeile and Melville wrote so vividly of the traps set for seafarers, a government publication in the Second World War was using remarkably similar language:

In most port areas ... especially by the dockside, there are cafes and public houses of low type which can only be regarded as traps for the unwary seafarer. In these he may meet women of undesirable character, and may be induced to spend part of his wages in drink and entertainment of a harmful character.38

In post-war Liverpool the same ‘traps’ were still there. The Duck House (because you had to duck your head to get in through the low doorway) disappeared with the old St John’s market, right in the city-centre, in the 1960s. With it went the Eurasia, a Chinese restaurant that brought together unattached seamen and prostitutes without customers after the pubs closed. One of the very last ‘traps’ still going – if tottering – was in Upper Parliament Street, described here by John Cornelius:

The Lucky Bar was open all night, every night. Depending upon which ships were in dock, it could just as easily be chock-full on, say, a Tuesday night as on a Saturday. The ‘business-girls’, as they called themselves, me to do as they did when trying to predict whether the club would financially worth a visit or not: get a hold of a copy of Lloyd’s List ... gave details of which ships were due in the Port of Liverpool. Ships, course, dock at any time of day or night. Frequently, the Lucky would be almost entirely devoid of male company, the girls sitting quietly around the place, waiting. But at any time the doorbell might ring and in would pour a gang of freshly docked ‘mushers’ (seamen) ready for anything, wallets bulging, banknotes flying like confetti.39

Melville would have understood the continuity, for, while he could be frightening in the language of his disapproval, he also knew that seamen were not quite so innocent. Regretfully, he recorded that

sailors love this Liverpool; and upon long voyages to distant parts of the globe will be continually dilating upon its charms and attractions, and extolling it above all other seaports in the world. For in Liverpool they find their Paradise – not the well known street of that name – and one of them told me he would be content to lie in Prince’s Dock till he hove up anchor for the world to come.40

Liverpool necessarily had a very large transient population comprised of visiting seafarers and those who, at least notionally, were domiciled in the city. In 1872 the Chief Constable estimated that at any one time the city had a shifting population of about 20,000.41 Although this figure is certainly inflated, the social life of the sailor ashore was not lived in some discreetly hidden and therefore ignorable quarter. The most notorious cluster of streets by the turn of the century were those in the vicinity of the Sailors’ Home (!), the Shipping Office, where crews were engaged and paid off, and the Seamen’s Dispensary which specialised in treating some of the better known maladies. These streets were part of the heart of the city, less than a five-minute walk from the columned entrance to the Liverpool branch of the Bank of England and other financial emporia. The port had two public presences and, if the one was celebrated as much as the other was deplored, each was equally expressive of how the sea and its commerce possessed the city.

Ships, docks, cargoes and the people associated with them were, at the beginning of the twentieth century, Liverpool’s past and future. In the twentieth century the city’s economy did diversify into manufacturing, but it came late, was never sufficient and was too impermanent to offset the dramatic and headlong decline of the port from the late 1960s. The condition of Liverpool today – economically, politically, socially – is a direct outcome of the changing fortunes of the port.

In the 1890s the one-sidedness of Liverpool’s economy had become a regular source of comment. The Liverpool Review remarked:

We are not great as a manufacturing centre. By the side of Manchester, Leeds, Birmingham, Bradford and smaller places we have as manufacturers to hide our heads.42

Comment had plainly become anxiety in the mid-Edwardian years, when one of the local evening newspapers, the Liverpool Express, ran a competition for schemes to diversify the local economy. ‘By 1914’, a historian wrote of the port, ‘the high peak of achievement had been reached and passed; the lean years were quickly recognised at the time.’43 In 1923 a group of local businessmen co- operated with the relevant city and borough governments to found the first local promotional body.

The Liverpool Organisation ... is influencing what people think about Liverpool the whole world over. It is broadcasting in every language its advantages as an industrial centre and as a great seaport. It is in touch with those who, abroad and at home, contemplate setting up factories in this country. It acts as a clearing house for information about the city, and ... it seeks, persistently, to further the interests of the people of Merseyside.44

The language of intent and ambition in this ringing declaration hardly varied at all in the remainder of the century as successor organisations set themselves identical objectives.

Before 1914 the Port of Liverpool accounted for 31 per cent of the UK’s visible imports and exports. By 1938 the city’s share had fallen to 21 per cent as measured in value. The port’s fortunes had for long been linked to the cotton industry and, as Lancashire textile manufacture declined, so too did Liverpool’s port. Britain’s industrial centre was shifting to the Midlands and the South-East and other ports were within easier reach.

After the Second World War, and with the post-war boom in full swing, the port did regain some of its lost export trade. In the mid-1960s the dock road was in a daily confusion of traffic; quays and dockside sheds overpowered by haphazard queues of crated and bundled and baled outward cargo. The regions of the world were still sea-laned to Liverpool. Almost within hailing distance of the Liver Building were small, low ships running to Paris via Rouen, and a mere ten-minute walk took in ships of varying sizes loading for Limerick, Barcelona, New Orleans, Demerara, Lagos and Manaus. Ford’s had opened at Halewood and sucked in hundreds of ex-seafarers, but it was still impossible to exaggerate how much the city of Liverpool was a seaport.

The main Post Office, next door to the Fruit Exchange, could offer its customers the scents of fresh Spanish oranges – or onions in another season. The produce had come into the city, via the North Queen’s Dock, carried by the white- hulled ships of the MacAndrew’s Line, whose faded and peeling offering of ‘fast cargo services to Spain’ remained on the gable end of a quayside shed for 20 years after the dock had closed. Berthed nearby, then, were the Booth Line ships which traded first to Portugal and then to Brazil and as far up the Amazon as Manaus. An illicit trade in green parrots was a sideline for crew members.

Tied up in Toxteth Dock, a swing-bridge away from the Booth boats, were Elder Dempster Line ships. These were known throughout the port as the ‘monkey boats’ because, where other ships kept cats, these had once kept monkeys. The monkeys became part of the folklore of the city’s South End and kept Elder Dempster’s nickname going, for they had done their bit in the Second World War. Late in the war, Captain Laurie James, then a young second officer, was in a convoy proceeding northward up the Portuguese coast and about to be attacked from the air:

Now we had a monkey on this ship and they were the finest spotters of planes going. They had a very acute hearing; we called them grass monkeys and they were very small. They were the pets generally of somebody on board and they’d be looking in the direction of the plane and you could see them getting excited. It seemed as if they felt there was something menacing. This was well known amongst those of us on the West Coast trade.45

Elder Dempster’s carried West African crews and had done so since before the First World War. Over the decades numbers of black seafarers had settled and married in Liverpool. They and their descendants provided a ready market for the yams, plantains and sweet potatoes sold to Granby Street shopkeepers by enterprising African seamen. African grey parrots, highly prized for their linguistic skills, also came off ships in the ‘West Coast’ trade. Some fetched prices still discussed in the bar-room talk of retired seafarers. Others ended up with Gran in the back kitchen, like the one remembered here by Matt Simpson:

My father’s brother brought it home,

madcap Cliff, a ‘case’, with wit as wild

as erotic dreams. It was his proof

of Africa and emblem of the family pride

in seamanship.46

The port also left its mark, if more obscurely, through its folk rituals. In the Protestant streets of the Dingle, at the southern-most end of the dock system, children ran through the streets at dawn on Good Friday dragging burning effigies of Judas Iscariot. As unknown in other parts of Liverpool as elsewhere in the UK, this was a Portuguese practice and seems to have arrived with the fruit trade. The Chinese New Year was an event in Liverpool long before the rest of Europe had heard of it.

For the entire length of the dock road, the pubs either bore the names of the adjacent docks – the Coburg, the Bramley-Moore – or appealed to the ships, hence the Baltic Fleet and Al at Lloyd’s. Lime Street, no less than La Canabière in Marseilles, had its American Bar and was similarly decorated with ships’ photographs and mementoes deposited by sentimental departing seamen.

The businesses lining waterfront streets also announced their dependent livelihoods: makers of flags and bunting; chandlers specialising in deck and engine-room stores; bleaching agents and holystones for scrubbing wooden decks; Lion Brand patent packings for steam valves and bales of colour-flecked, grey cotton waste to clean engine-room ladders and plates. Firms making paint, firms selling other people’s. Spinnaker Yacht Varnish: well spoken of by foremen painters in Solent yacht-yards and made in Liverpool to withstand the weather thrown at the woodwork of ocean liners. Tarpaulin and sailmakers. Ships did not forsake canvas when they got rid of their sails. Around the most modern motor ships there was canvas everywhere. Canvas awnings to shade decks in the tropics, covers for the deck lockers containing the awnings. Tents for open hatches and at least three tarpaulins to cover the forward hatches when at sea. If the fancy canvas for gangway screens was made by the ABs (able seamen), the rest of it was cut, shaped and sewn ashore in the lofts that had once supplied sailing ships.

The irregular roof line of the landward side of the dock wall peaked with the grain and sugar silos, the warehouses in grey-trimmed red brick, the undecorated castles of commerce giving shelter to bales of wool and cotton. The city itself broke through the workaday buildings, stood over the regiments and battalions shifting cargoes, driving lorries, caulking decks – and calculated their wages. At the Pierhead the city intrudes into the docks and divides them into North and South. Here are the grand buildings of Edwardian opulence, fronting for the wealth once made in owning and insuring ships; in lending money to the merchants who bought and then sold unseen the raw materials carried on homeward passages. Here in Liverpool’s City there were other and better dressed regiments at work. Bowler hats and rolled umbrellas were as de rigueur in Water Street as in London’s Leadenhall Street. On the morning and evening ferries across the Mersey the bowler-hatted, and those aspiring to the same rank, promenaded, anti-clockwise and four abreast, around the boat-decks. The old custom was defiantly maintained in the late 1960s although the ranks had thinned compared with the phalanxes once common. The business side of ship operation and other shipping services, not to mention banking and insurance, were all labour-intensive activities. Thousands of office workers poured into the city every day – clerks and typists from the inner suburbs of Liverpool and Wallasey, managers and directors from West Kirby and Blundell Sands.

Moving ships, cargoes and money from one part of the world to another by telex cable was, on its own, a fair-sized economy with its own ring of satellite firms. Every large firm had its organisational formula and accordingly provided work for the local printshops and bookbinders. Ships’ chart folios went ashore to chart correctors’ offices for the latest marine hazards to be entered in indian ink; ships’ chronometers and barographs were landed to be cleaned and rated. Men from Sperry, Marconi and Decca went down to ships to check gyro compasses, radios and radars respectively. Board of Trade surveyors checked ships’ safety equipment while their examiner colleagues tested and grilled the young mates and engineers temporarily ashore studying for their certificates of competency.

In other offices scattered around the city were the average-adjusters to settle claims between the insured and the insurer; the ship-brokers to buy, sell or charter a ship; the freight forwarders to arrange shipment of crates or bales of anything to anywhere; the agencies to handle the business of foreign ships; the foreign consular corps to guide and advise resident and visiting nationals. The Dock Board, in its magnificent offices of marble and mahogany, had its own army of clerks, managers and superintendents to watch over and log in and out its revenue and expenses, its pier-masters and dockgatemen, the crews of buoyage ships, dredgers and floating cranes; the gangs of skilled tradesmen and their labourers who ran the internal railway system, the water hydraulic lines and pump- houses which angled cranes and swung bridges; the shipwrights, millwrights, boilermakers, ironmoulders and blacksmiths who made and maintained the lock- gates and their machinery.47

A ship arriving in daylight would be certain to find on the quayside waiting groups of men whose purposes were in their clothes and in their manner. A dark- suited and homburged Marine Super come to welcome home his charge and wanting a briefing of immediate ship’s requirements from the master. The master stevedore to see the Mate about readiness to discharge cargo and to say what he wants first out of the holds. The riggers waiting to clatter their boots up the gangway, to open up hatches and top derricks. Customs rummagers to look for contraband. The Port Health wanting reassurance on the absence of infectious diseases. The union reps come to collect dues, pin down evasive members and hoping to avoid complaints. A tailor’s runner, briefcase bursting with samples of suitings, swift with the tape and the sizes into dog-eared notebook, talking constantly of other ships just in and how he saw old so-and-so only yesterday. More sheepishly, a Mate newly gone ashore tours the officers’ accommodation hopeful of selling some life insurance. With bonhomie, a padre or two from the Church of England Mission to Seamen and the Roman Catholic Apostleship of the Sea come looking for the faithful, the sad and lonely, leaving calling cards and posters advertising their service. Less welcome by far, the evangelical tract pedlars for whom seafarers might imaginatively ham up their sinfulness.

On the first night ashore the port’s evening economy provided voluntary as well as revenue-generating services. Of the former, and hugely popular with seamen, were the dances run by the Apostleship of the Sea at Atlantic House. Parish organisations were then still strong, parishioners still obedient and young women kept close to the Church. It was almost sufficient for the word to go out from Atlantic House to the parishes and dozens of women would arrive to do their Christian duty and dance with the seamen.

When the whaling fleet docked in Liverpool overnight to discharge its cargoes of Antarctic oils, women distinctly lacking the priesthood’s approval were in town and in number. On those nights Lime Street could seem like a Hollywood set of San Francisco in the days of the gold rush. The men came uptown from the Gladstone Dock with a lot of money and a determination to obliterate the six months just spent in the frozen wilds of South Georgia. The big money and the number of men drew women in from St Helens, Wigan and Salford.

Of the other Liverpool that had little to do with ships except through family and history, a substantial part either lived off processing cargoes or worked for firms needing the volume generated by ships to cover their basic costs. Ships arriving from a foreign voyage brought with them a hidden cargo of dirtied bed linen and towels that sustained a number of laundries. Neither was it a coincidence that Britain’s largest dry-cleaning firm, Johnson’s, was close to the local waterfront; it had a handsome business in cleaning the curtains and loose covers from the public rooms of the passenger and cargo liners. Bits and pieces of port-related employment of this sort contributed many hundreds of jobs to the local economy – but not nearly as many as the big processing industries.

At its peak, the port provided direct employment for perhaps as many as 60,000 people. Almost as many again worked in the processing and manufacturing industries that were only in Liverpool or its close hinterland through a dependence on the port’s commodities. When Bryant and May built their model match factory close to Garston Docks just before the Second World War, they could draw upon the standards of Baltic timber brought in on lop-sided ships. It made sense, too, for BICC to build its insulated cable factories on Liverpool’s borders: ships of the Blue Funnel brought in latex from Malaya and Sumatra and those of Pacific Steam carried copper from Chile. Lever Brothers at Port Sunlight took copra off the Bank Line ships which had ferried it home from the Pacific Islands and palm oil from Nigeria off ships of their own fleet – and then gave it back again in bars of soap to be distributed around Scotland and the North-East of England by Coast Line’s weekly sailings to Aberdeen and Newcastle.

The British American Tobacco Company made cigarettes and Ogden’s pipe tobacco from leaf brought in by the Harrison boats from South and East Africa and the USA. And so the connections went. The mills of Rank and Spiller and Wilson ground the grains of Canada and the US Midwest while Joseph Heap’s mill husked the rice of India and Burma. The Crawford family’s factories mixed, so to speak, Rank’s flour with Tate and Lyle’s sugar to bake their biscuits. Meanwhile and nearby, other factories – Read’s and Tillotson’s – made tins and cartons for the biscuits and the cigarettes. Courtald’s first rayon plant – then British Enka – overlooked the Grand National course in the suburb of Aintree and fed itself on imported Canadian woodpulp. Evans Medical, later absorbed into the pharmaceutical giant Glaxo, began life in docklands producing tinctures, powders and pills from exotic spices, roots, herbs and seeds. Before finally leaving Liverpool, Tate and Lyle had absorbed all its other cane-sugar-refining competitors in the city to become the largest refinery in the world.

A manufacturing sector independent of the port did develop in the inter-war years. ‘The Automatic’, later part of Plesseys, produced telephone exchange equipment, employed 16,000 at its peak and was just about the only representative in Liverpool of the growing consumer durable industry of the 1930s. Elsewhere in the city during the same decade, rearmament saw huge new factories making air frames, vehicles and aero engines. These were the very first factories to be directed by central government to Liverpool and represented recognition by the state of Liverpool’s need for a more broadly based economy.

The armament factories were sold off shortly after 1945 to become satellite factories for English Electric, GEC, Lucas and Dunlop. Ironically, these were among the first to be caught in the big wave of factory closures in Britain in the late 1960s and which continued through the 1970s and 80s. It was unfortunate for Liverpool’s working people that the desperate attempts by senior British managements to overcome their archaism and incompetence, which produced the flood of factory closures, should have come at a time when the port was suffering from the final expiry of the imperial connection, entry into the EEC and containerisation of non-bulk sea-borne commerce.

Since the 1920s there had been an underlying shift of the axis of UK manufacturing industry away from the North of England, Scotland and South Wales to the South-East, so attempts to attract factory-based employments had always gone against the national trend. The Liverpool Daily Post reported in 1954 that, although nearly 60 non-Merseyside firms (including Dunlop, GEC and others) had opened factories and created jobs for 27,000 people, this had not been sufficient to alter the economy of the area radically.48 Five years later Mr John Rodgers, MP, Parliamentary Secretary to the Board of Trade, said that no area of similar size anywhere in the UK had remotely comparable employment problems. He went on to say that, although new factories were being built, progress was still not good enough.49 The outlook had not improved in 1962 when the North-West Regional Board for Industry said: ‘The amalgamation and rationalisation of firms on Merseyside was resulting in a loss of employment opportunities in an area where unemployment was a serious problem.’50 The car industry, then arriving, was to provide only temporary relief. The port and its related processing industries therefore continued to provide the city’s core. Although the number of jobs centred on the port steadily shrank during the 1950s and 60s, it could still appear to be the one area of economic activity that was deeply rooted.

Until the mid-1960s the Port of Liverpool’s share in the national totals of imports and exports had remained more or less constant. Liverpool’s prominence came from cargo liners and these, of course, were precisely the type of ship that were soon to be replaced by the container ships.

The movements of manufacturing industry, population and wealth to the South-East inevitably made that region’s ports more attractive to shippers of goods. The coastal ports of south-eastern England, being tidal, were also much cheaper to use than Liverpool’s enclosed dock systems, which were expensive to maintain. At the same time the decline of Commonwealth countries as trading partners and the rise of EEC countries left Liverpool marooned on the wrong side of the country. Between 1966 and 1994 Liverpool’s share of all ship arrivals in the UK was halved, while Dover’s share increased four-and-a-half times. By 1994 the East coast ports had totally eclipsed the importance of those to the West. The following league table of UK ports in 1966, 1994 and 2011 provides a neat illustration of the transformation of Britain’s patterns of seaborne trade.

Table 1: Ten largest UK ports, 1966, 1994 and 2011*

| 1966 | 1994 | 2011 |

| 1 London | 1 London | 1 Grimsby and Immingham |

| 2 Liverpool | 2 Felixstowe | 2 London |

| 3 Tees and Hartlepool | 3 Grimsby and Immingham | 3 Felixstowe |

| 4 Manchester | 4 Tees and Hartlepool | 4 Dover |

| 5 Clyde | 5 Liverpool | 5 Liverpool |

| 6 Hull | 6 Dover | 6 Tees and Hartlepool |

| 7 Newport (Mon.) | 7 Medway | 7 Southampton |

| 8 Bristol | 8 Port Talbot | 8 Belfast |

| 9 Port Talbot | 9 Hull | 9 Hull |

| 10 Grimsby and Immingham | 10 Southampton | 10 Medway |

Source: National Ports Council (1967) and Department of Transport (1995 and 2012)

*As measured by volume of foreign and domestic non-oil traffic for 1985 and non-fuel traffic for 1966.

Between 1966 and 1994 the relative importance of East and West coast ports was reversed. In 1966 there were only four East coast ports in the top ten, whereas in 1994 there were only two West coast ports. Dover and Felixstowe, which together handled one-ninth of the volume of Liverpool’s goods in 1966, were handling 20 per cent more than Liverpool in 1994. By 2011 Liverpool was the only West coast port remaining in the top ten. Containerisation went in parallel with the shift of traffic to the East coast, although the timing of the two movements was largely a coincidence. The impact on port and shipping operations of the containerisation of cargoes was swifter and greater than the transition from sail to steam. Until the 1960s ships carrying frozen or manufactured goods were loaded in much the same way as furniture removal vans – giving due consideration to stability, items were packed in accordance to shape and with a view to minimising lost space. In 1927 it was reckoned not surprising to see in the list of cargo of a ship loading for the Far East:

a ton or two of bicycles, a ton of metal polish, three tons of sewing thread, two of boracic acid, nearly a ton of blotting paper, ten tons of biscuits, a hundred of soap, twenty of whiskey or stout, and as much as four tons of assorted chocolates.51

If the list was perhaps slightly different by the 1960s, a comparable variety was nevertheless packed into the same space. Even homogeneous cargoes like cane sugar were still coming into the port in bags until the early 1950s – and the description which follows of moving from bagged to bulk sugar stands as a useful analogy for the transition from handling individual goods to stowing containers:

The first bulk cargo of raw sugar was received in Liverpool, in the S.S. Sugar Transporter, in August 1952, and, once bulk receiving started, the amount in bags gradually decreased to vanishing point, taking with it the old-fashioned method of weighing at the docks, the trailer wagons that carried the bags to the refinery and the gangs whose job it was to open and empty the bags in the silo bays, which now stand generally idle. Gone, too, was the livelihood of the man who made sack hooks.52

The containerisation of general cargoes was first successfully introduced in the 1950s on the West coast of the USA, where it showed spectacular savings in the time ships spent in port. One US study showed that where it took 10,584 working hours to load and unload 11,000 tons of general cargo it took only 546 working hours to load and unload 11,000 tons of containers.53

The capital cost of containerising general and frozen cargoes was simply enormous; special ships had to be built; quays and cargo-handling equipment reconstructed and replaced; stocks of steel boxes built up; compensation paid to dock labourers whose considerable skills were being made redundant. This gave a premium to new port sites like Felixstowe, where there were no costs involved in scrapping obsolete equipment and no compensation to be paid to displaced workers.

The most visible consequence of containers, and the one the public knew about, was the large reduction in the number of dockers’ jobs. Less visible, because hardly publicised, were the effects on seafarers and those who serviced ships. Container ship operation became almost identical to that of tankers, which had for long been accustomed to port turn-around times of less than 24 hours. This mode of operation meant that most ship maintenance was done by ships’ crews rather than by ship repair firms who had previously swarmed over vessels during their lengthy stays in port. For their part, seafarers were plainly affected by a type of ship that on the Australasian routes, for example, halved the voyage time once normal (from five months to two-and-a-half), could carry the equivalent of six traditional cargo liners and needed only half the crew of one of them. These ships, too, were now completely bare of their own cargo-handling gear, while a conventional six-hatch ship had had 20 derricks, each with its own set of winches. Here there were effects upon the rigging lofts and the rope manufacturers. Shipowners themselves, now operating fewer ships, no longer needed such large staffs ashore, creating yet further employment consequences.

It took little more than a single decade for Liverpool’s port to shrink so much that it became almost unrecognisable. Herman Melville and all those other celebrated nineteenth-century visitors would still have found something to recognise in the mid-1960s, for although ships might have changed, the cargoes they carried and the methods of handling them were sufficiently similar to have been recognisable. By the early 1980s most of the dock system had changed and been converted to other uses. The port that had created Liverpool had dwindled to insignificance and left the city with huge economic and political problems.