Читать книгу Oasis - Tony McCarroll - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CONTEMPT BREEDS FAMILIARITY: A MANCUNIAN CONCEPT

ОглавлениеWe don’t deny the fact that we take drugs such as cocaine, marijuana and ecstasy. We’ve been doing drugs since we were 14. In Manchester there are only three things you can do when you leave school – play soccer, work in a factory or sell drugs.

NOEL GALLAGHER

Noel’s career advice may sound like simply a useful sound bite for the Oasis cause, but it was not that far removed from the truth. We decided a life of crime was the only way for us to pull ourselves away from the violent streets. In an attempt to find a bit of peace, we formed a hooligan gang. (I know.) As a tribute to The Smiths, we named ourselves the Sweet and Tender Hooligans. (Like I said, I know.) Each member wore a green survival jacket with attached hood. This hood had goggles stitched into it, and we would hide behind these when in action. The coats were purchased from the army and navy store on Oldham Road and must have been made in the early days of the Cold War. There were four of us in the gang: Guigs, Me, Crokey and Fantastic. Noel had told us we were off our tits and refused to have anything to do with it. Maybe it was the Smiths connection he didn’t agree with.

Our first criminal enterprise was financial extortion. This dangerous-sounding idea was borne from watching Once Upon a Time in America on pirate VHS loop in Guigs’s house. We first targeted a television shop on Barlow Road – the road that Guigs lived on. The shop was even visible from the house itself. First unwise decision. What’s more, the shop was run by a bunch of Italians, who never seemed to spend time fixing televisions. They seemed to sit around and drink coffee and meet the different people who visited each day. You’d think that after we’d seen that video, this might have rung a few alarm bells. Oh no. So there came the second unwise decision.

One afternoon, Crokey was pushed through the shop door and mumbled some sort of demand in the dark and gloomy shop. When the large Italian lady standing tall behind the counter asked him to repeat himself, he turned on his heels and simply left. We all hurriedly returned to Guigs’s house and asked Crokey what he had said. He told us he had got nervous and lost the plot, so he’d used a line from Once Upon a Time in America. The only one he could remember. What was the line, we asked, expectantly? ‘Erm… “So what are you? You’re filthy! You make me sick! You crawl up toilet walls just like a roach! So what are you?” ’

‘That’s all you said? Just those words?’ I asked him. He nodded. The quote he had used in the shop was uttered by a young girl in the film and was aimed at a peeping tom she had caught. I spent a moment trying to see the relevance and then realised there wasn’t one; I shook my head in disbelief at Crokey and reckoned the old Italian lady probably had him down as a local lunatic. I was wrong.

Later that evening, we were sat in Guigs’s house when there was a sharp rap on the full-length, glass-frosted front door. We poked our heads out to see the hallway darkened by a huge, lumbering figure hovering at the door. ‘You get it,’ Guigs whispered.

‘Fuck that, you get it,’ came the general reply.

We had a silent whisper argument for 30 seconds, until Guigs cracked and trembled up the hallway. It was his house, so he was in a difficult position. As he opened the door, we all listened.

‘You come in the shop again we will come back with shotguns and give you some ventilation, capiche my little pig-like friend?’ Said in the thickest Italian accent I had ever heard.

I was dying to crack up laughing, as it had to be a piss-take, so I poked my head carefully round the door. It was no piss-take. Standing there was the most terrifying-looking man I had ever set eyes on, a man made for nightmares. His face looked like it had seen the wrong end of a couple of hundred brawls and his dark suit was bursting with the 200lb of pumped muscle it contained. He emanated evil and pain and possible torture. Well, I might be being a bit dramatic there. It was more a crack with a baseball bat and a severe warning.

Guigs whimpered, ‘Sorry, sir.’ At that point, the Italian simply growled back and thrust his head forward, as if to attack. Guigs immediately hit the hallway floor and took up a hedgehog-like defensive position. This went unnoticed by the Italian as, after growling, he had swiftly turned on his heel and marched down the garden path, slamming the gate behind him. We slowly coaxed Guigs from the hallway with a saucer of warm milk. The lesson we learned here was: never try to enforce a protection racket charge upon a large Italian organisation that obviously had fingers even in little old Levenshulme. I guess the life of a racketeer was not to be an option, so it was back to being the butcher boy.

Over the next year or so, I continued to work at the butchers and saved enough to eventually get myself that new kit. I also finished my secondary school education at St Albans High School in Gorton and was now able to make a small boat out of balsa wood as well as a pretty good apple crumble. So, armed with those two amazing talents, I was released into the adult world.

The five-a-side court had literally started to crumble around us and people had begun to move on. The only activity that still united the group was the fortnightly away trip with Manchester City and, for those that could afford it, a night out in the boozer at the weekend. We normally drank in the Irish boozers in Levenshulme, but would sometimes travel further afield. The Horseshoe, The Midway, The Church and The little Vic were the designated watering holes; if we were feeling adventurous, we’d head upmarket to Stockport or Didsbury.

One Saturday evening, we made our way to a club called Shakers in Stockport. When we arrived there was a large queue, but we found ourselves being shouted to the front. Standing at the front was a beaming doorman. It was the Policeman. He had been taught how to fight by the six brothers, which inevitably led him into the murky world of door security. There he stood, hand out ready to shake, looking extremely professional in his monkey suit and crew cut. We had trained together over the previous four years or so and had developed a strange relationship. The Policeman had proved to be quite an adept boxer and had, not surprisingly, taken to the ring. His only problem was that when he fought he could turn into a wild man, which made him difficult for the six brothers to manage.

An example. I was sitting in a dressing room as four hundred or so boxing spectators were baying for blood outside. It was Levenshulme ABC’s own show, so I was tasked with keeping an eye on the changing room and its contents. Easy work, I thought. If a thief were picking out a target, surely a boxer’s dressing room wouldn’t be that high up on the list? There was a right commotion going on outside. I peeked out of the door. The crowd was angry and was ferociously hurling obscenities toward the ring. The spotlights illuminated the wispy layers of smoke that hung over them. A loud, long booing rang around the old hall. Suddenly, the Policeman appeared, on his way back to the dressing room. He was sweating and scuffed, his face still reddened from the fight. ‘Right, fuck this,’ he snarled.

I didn’t think the Policeman was very happy. It seemed he had once again gone a bit mental during the bout and had butted his opponent three times. This had been at the end of a fight that he was easily winning. Apparently, his opponent had pressed a button by whispering something to the Policeman, prompting the violent outburst. This, in turn, led to the referee disqualifying the Policeman; he did so, quite wisely, from the other side of the rope.

The Policeman was now swinging punches inside the dressing room as if he were still inside the ring. ‘Left, left, right,’ he hissed under his breath. ‘Left, left right.’

Suddenly the dressing room door opened and in walked the victorious opponent. He was smiling until he saw the Policeman at the far end of the room. The Policeman walked towards him, also smiling. But I recognised the smile and realised the victor wasn’t going to enjoy his spoils for long. The Policeman motioned me out of the room with a simple look and nod of his head and as I pulled the door shut I heard the thick thud of his right hook connect. With perfect timing, the large brass bell rang out to start the next fight of the evening.

By the summer of 1987, Guigs had got himself a job at Barclaycard in Manchester. At around the same time, he seemed to become more and more withdrawn. This, I soon realised, was due to his fixation with marijuana. Back then, if he wasn’t reading about it, he would be smoking or eating it.

I finally got myself a good number in a local insurance office in Burnage. Right on my doorstep and normal hours. All I had to do was answer the phone and point people who came in to the right adviser. All of this and out of reach of the Mancunian rain. I considered myself fortunate to have landed on my feet. I was 16 years of age and on my first day found myself overawed both by the job and by a young girl who blushed when I asked her name. ‘Paula,’ was the reply.

And then there was a large bang. In late 1988, an explosion of love hit the streets of Manchester. One little white pill had sucked the hatred and frustration from a scarred generation and replaced it with a weekend euphoria and a new belief.

One winter night in 1988 found me sitting in The Millionaires Club in Fountain Street, Manchester city centre, surrounded by two hundred perspiring and grinning lunatics. They filled the dance floor and none of them were millionaires. Everybody had a prescription and all were ecstatic. It was Saturday night. Both City and United danced a communal dance, while all the girls were suddenly less interested in themselves and more interested in me. Or so it seemed. That situation was good for me.

Not that night, though, as I had Paula waiting back at her house. I had progressed both as a insurance customer service adviser and in my pursuit of the young Paula, from Burnage. She was probably what kept me punctual and interested in work from Monday to Friday. After a couple of weeks of chasing, she succumbed to my caveman charm. Paula was a good girl and had a generous nature. Although I had only been with her for a few months I could sense something good happening. I was 17 years of age.

After hailing a cab I weaved my way through the rainy city centre and arrived at her place. I was still chewing, still euphoric. A new-found joy pulsed through me. Paula stood in the doorway, waiting for me. Her arms were folded.

‘Hiya, Treacle,’ I said with a smile as I paid the taxi driver and walked up the short path. She ushered me inside and sat me down. I had a bad feeling. Something was wrong. She looked me straight in my dilated eyes and said, ‘You’re gonna hear the pitter patter of tiny feet around here soon.’

‘Why have we got mice?’ I replied. She ignored the joke.

The cold light of the next morning brought the inevitable comedown and the sheer panic that the previous night’s news had created. I was bringing a kid into the world. I realised that meant I would need a new job. Paula would have to leave the office and what I was earning alone would not cover us. But none of that mattered, because I was bringing a kid into the world.

I was still running around with the gang from the park. Not so much during the week, though, as I was in practice for the arrival of my firstborn. They had all shaken my hand when I told them I was going to be a dad, but celebrations were muted. We all knew that it meant a change. But I would still travel to City away games occasionally. Noel had broken his foot and had been shifted to the stores of the construction company where he worked. He seemed very happy about this. Guigs had given up filing for Barclaycard and was now filing for British Telecom instead. He didn’t seem so happy about this. Liam had just been thrown out of school for having an altercation with somebody that resulted in Liam being hit with a hammer. Big brother Paul was still working the roads.

It was a bright Saturday morning in spring 1989, and I had a trip to Forest away. As usual, we met outside Johnny’s Café in Levenshulme. From there we made our way to Levenshulme train station and, with family rail cards in hand, headed to our destination. Our family consisted of one adult and 33 teenagers. This family had been causing havoc up and down the country for a good three years already. That day it was Nottingham’s turn. We laughed on the way down. The previous week, Vinny Collins, my football manager, had decided to have a pint in Stockport before City played them in a friendly. It had been a covert seek-and-destroy mission. His intention was to infiltrate County’s hooligan pubs and then guide the rest of City’s troops in. Vinny, though, had drunk a little more than he should have and went missing in action. Nevertheless, the City firm decided to go ahead and storm the local boozers. Can you imagine their surprise when they arrived to find a right handy mob being fronted by Vinny himself?

‘Get outta the fucking way,’ they shouted over to Vinny.

‘C’mon, shitbags,’ Vinny roared back, at the top of his voice. Then he put his hands to his face and blew an imaginary horn while making a noise that you would normally hear at the start of a fox hunt. He moved forward and beckoned Stockport to follow, right into the front of City’s firm, while he laughed. Back in Manchester city centre later on, some of the City lads weren’t happy with Vinny’s antics, but he soon had them turned round and laughing again. ‘It’s just a bit of pub fun,’ he would say.

That morning, Vinny looked visibly excited about the trip. He asked if I’d seen Jimmy the Butt and told me to say hello to him. We all jumped on the train and soon arrived in Nottingham city centre. BigUn was leading the way, with his usual scallywag style. Burberry coat with collars pointing to the skies to reveal the trademark pattern underneath. At that time, it simply let everyone who mattered know you were a hooligan and ready for it. Now it seems it just lets everyone know you’re a ‘chav’. How times change.

‘BigUn’ was Paul Ashbee, who was about the same age as Noel. He was a local lad who stood 6ft 5in tall and 2ft 6in wide. I think he was best left described as entrepreneurial, although he was definitely a ‘Spartan’ (meaning ‘well liked and respected’). Over 30 of us had jibbed the train without any hassle at all. Fuck knows how much the travelling away fan cost British Rail in the eighties. We had met up with Richard Jackson and Bad Bill from Salford. They had a tasty firm, so we decided to split into two groups; I was with Noel and BigUn and Jacko, and we marched off through Nottingham city centre. Across a busy street we spotted a group of twenty or so appropriately dressed Forest fans outside an amusement arcade. Space Invaders and Donkey Kong were to be an electronic prelude to mass violence, it seemed. BigUn immediately started to bounce and then, without even a word to anyone else, he screamed, ‘C’mon, dickheads, let’s have it!’

Not really part of the plan, but that never did stop BigUn. I’d always wish that he had been better at mathematics when deciding to start such things. The odds were already stacked against us as the opposing group started to rapidly increase as the inside of the arcade emptied onto the street. The Forest fans were now excited. Shit, I thought, I wish Jimmy the Butt was a Blue. We were the youngest of City’s firms and way out of our depth. The Forest fans reached about seventy in number, then suddenly began streaming across the road towards us. I looked at Noel, who looked back terrified. ‘Fuck this,’ he shouted and was off on his toes.

His damaged foot apparently causing him no problem whatsoever, he was gone, a vanishing Mancunian flash. The rest of the group followed him. I panicked and looked around. As I turned to run, I saw BigUn in the middle of the opposing group. He was throwing his fists around, trying to stem an unstoppable flow of opposing supporters. Lunatic. I headed off into the more commercial part of the city centre, knocking shoppers out of the way. The Nottingham firm were buoyed by our retreat and poured after us. My cross-country training at school came into play and I moved from the back of the group towards the front. Then my 20-a-day habit kicked in, and I was soon being passed. As I glanced over my shoulder I saw Jacko run straight into a bus shelter and hit the pavement, scattering panic-stricken shoppers. He was quickly set upon by the following pack. I contemplated turning back, but there were just too many of them. Suddenly, as I rounded a corner, I spotted Noel and a couple of others slipping into a darkened doorway. A look of terror was pasted across his face. I followed and we headed down the dark stairwell into a cellar bar. We ordered a round of drinks and took a seat.

The pub had long wire-mesh horizontal windows, set at street level. Outside, I could see thirty or so pairs of Adidas, Nike and Reebok trainers. Oh and the occasional pair of Patricks. If they clicked where we were, we would be in for a right slapping. I sat and watched the stairway, fully aware that it was the only way in and the only way out. Time seemed to slow down. The rest of the bar sat looking curiously at the four out-of-breath arrivals. I looked to Noel, who was as white as a sheet and murmuring something unintelligible over and over to himself. I quickly realised that my hooligan days should probably end before they really ever began. After watching Noel slowly stop shaking, we finished our drinks and headed swiftly and quietly to the ground.

I was working my way down the tick list. I was no criminal. I was no hooligan. I had a moral issue with dealing drugs, so that wasn’t an option. What options had I left?

Anyone seen me drumsticks?

She had arrived. As my father had held me aloft only 18 years previously, in the summer of 1989 I raised my daughter to the world on the very same ward. We named her Gemma and sat in awe. I made some promises that moment. I will always love and cherish you. I will always be there for you. I will let no one harm a hair on your pretty little head. I decided it was time for a change. A new direction. If I was to look after the beautiful ray of sunshine that I held in my arms, I needed to find better work and a less chaotic place to live.

Gemma was one arrival that changed my life in 1989. The debut Stone Roses album was another. The arrival of that LP would send a new swagger down rainy Manchester streets. The detachment and frustration of a generation had a new beat with which to march. And fuck me, it was a cool one.

Spring 1990, and it had been a couple of months since I’d last seen Guigs. He’d rung earlier that evening, though, and said he needed to see me urgently. I was sitting in a Levenshulme pub called The Church, staring out the window at the insurance shop where I worked, which was directly across the road. I spotted Guigs slowly ambling up Stockport Road. It was good to see him. Two people accompanied him, one on either side. I recognised one as Huts, the lad who Liam had fought with in the park. I didn’t recognise the other one. As they entered the pub I was waiting at the bar.

‘Hiya, mate.’

‘Hiya, fella.’

It was hugs and back-slapping between myself, Guigs and Huts. Standing silently behind them was a very happy-looking fella with an open face and eyes that seemed slightly unfocused. They then introduced me to one Paul Arthurs, better known as ‘Bonehead’. He stood before me with his hand out and an odd look in his eye, which was exacerbated by a Max Wall-like hair do. It looked like The Church wasn’t the first pub he’d been in that day. We shook and, after a short introduction during which Bonehead’s unique style of humour became immediately apparent, we made our way to a booth in the darkest corner of the pub.

‘We want you to drum for us,’ said Guigs, before we had managed to sit down.

‘We’re the new Roses,’ added Bonehead. With this outlandish statement, he swaggered off to the bar in an Ian Brown monkey-style slalom walk. I had been practising my drumming intensely over the previous 12 months and had rehearsed with all manner of different bands. My influences had diversified. I had been watching old videos of John Bonham in action, which had left me completely stunned and hungry to drum. I also found The Stone Roses’ drummer Reni particularly inspiring, with his unique lazy beats. Guigs went on to explain that he had met Bonehead at a student club called Severe in Fallowfield a couple of months earlier. Bonehead was a childhood friend of BigUn. It seemed that he was a talented musician, too. Guitars. Keyboards. Mouth Organ. Radiators. You name it, Bonehead could get a tune out of it. He had been able to play the keyboard at four years of age, which had led to the local kids naming him ‘Mozart’. He had encouraged Guigs to learn to play something and, as the bass could be played by a blind monkey, decided that that instrument was a good starting point. Guigs’s Mr Benn Syndrome had, hopefully, finally paid off. I had always known that his attitude would serve him well. You had to admire Guigs for his desire to try something different.

Bonehead was a few years older than both me and Guigs and he had grown up in West Point. West Point was officially the ‘west point’ of Levenshulme, but like some rebel state, those there considered themselves a separate entity altogether. As if there wasn’t enough segregation at the time. Although massively outnumbered, kids from West Point would frequently clash with Levenshulme as well as Burnage. That, in itself, gave them some respect with the surrounding gangs.

It didn’t take long for me to warm to this mop-haired plasterer. He had the ability to down alcohol like no one else I had met, a talent that, it seemed, he had developed at an early age. As a 13-year-old, he would be regularly returned home unconscious from the park. Once it started to flow it just couldn’t stop for Bonehead. Fortunately, he was that rare breed: a good drunk. His mother and father hailed from Mayo, but he wasn’t your stereotypical Levenshulme lad. He had attended a grammar school but had not enjoyed the experience in the slightest. It had left him with a wry and eclectic sense of humour, though, somewhat Spike Milligan-esque. He was also as talented as any musician that I had ever come across. Sober, he was as witty and sharp as anyone. Focused, but funny. Drunk, he was like a one-man circus sideshow. Always fun. In the sober moments he would become a close friend and a source of trust and support.

He was standing at the bar in The Church, ordering drinks in fragmented German. The sturdy barmaid looked as if she was about to pot him, although Bonehead seemed oblivious to this. Guigs and Huts were obviously impressed with his musical nous, if not his mental stability, so I agreed to come to the Milestone boozer on Burnage Lane the following Saturday to see them in action. I watched as Bonehead frogmarched round the bar, his finger under his nose as a substitute Hitler moustache. It was like watching a mental patient on the loose. Luckily for Bonehead, it was the type of pub where you could easily have assembled a cast for One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, so he carried on.

Guigs told me that Noel had got a job for the Inspiral Carpets as a guitar tech and was touring all over the globe, which seemed pretty impressive and also explained his recent absence. I wondered how the fuck he had managed it. Good on him, though. Noel had played his acoustic guitar in the park for us; he wasn’t bad. Guigs and Huts were keen to get him on board with the band, or at least have a chat. I thought that Huts’s bowling-green altercation with little brother Liam would have got Noel’s back up, so even before they asked I knew it was gonna be a no-no. But I knew I had to make changes in my life if I was going to provide for the new arrival. Something already felt good about the band. Another kid that we had met through the park was Max Beesley. His father was a famous jazz drummer and Max was more than capable himself with the sticks in his hand. I asked Guigs to sort out a meeting for me with Max’s dad next time he was round.

They finally left after Bonehead had got the whole pub in uproar with his antics. I liked him. After they’d gone, I sat staring out of the dirty pub window at the insurance office. Would this finally be a route out of my mundane, shithole job? Something good to break the monotony? I hoped my luck would kick in. Lord knows it would have been the first time.

It was a beautifully cold day. The crisp air followed Jimmy the Butt through the front door. He would often drop by for a cup of my Mum’s sweet Irish tea.

‘How’s the music going?’ he asked.

‘Good mate, good,’ I replied, and told him about Guigs and Huts and Bonehead. Jimmy beamed and congratulated me on my efforts, but he didn’t look himself. There was a crack in the smile. As much as he tried to steer clear of trouble, it seemed it would always seek him out. It was difficult for him to be beaten one to one, so he was now finding himself up against two or three at a time. He had recently started a proper relationship with a girl and this seemed to be preying on his mind too.

‘Do you understand them?’ he asked. Must mean women, I thought, and shook my head. Now that I had a permanent girlfriend and a child, it seemed that Jimmy believed I understood relationships. If only. I told him to enjoy her and not think about it too much. Jimmy didn’t seem to be listening to my advice and just sat staring into space. After a few moments, he grabbed my hand in his massive paw, gave it a shake and told me I was a good kid. He then told me once again that some things are right and some things are wrong. Act on them. With that, he gave me the grin of a wild man and he was off out the front door. As he left, a strange, uneasy feeling came over me. I shook it away.

A month later, Jimmy was gone forever.

I noticed the hastily designed poster advertising The Rain, who were playing the Milestone pub in Burnage one night in the summer of 1990. It had been covered in plastic to protect it from that evening’s downpour. What a fuckin’ miserable name, I thought. Who wanted reminding of rain in Manchester? Inside, the ‘new’ pub was full of chest-high tables and stools that you needed step ladders to climb onto. At the far end of the pub, slightly off the bar, stood Guigs, Bonehead and Huts. The band. Next to them was every drummer’s enemy: the drum machine. Chairs had been laid out cinema-style before the band and were filled by friends and regulars. Chris nervously shuffled from foot to foot. He was a good lad – somewhat excitable, but extremely enthusiastic and a good spirit. A definite Spartan.

The show started, and I began watching Guigs intently. He had told me that Bonehead had given him a crash course in bass playing and to his credit he was there and he was actually playing along, in time to the rest of the band. I was impressed. A couple of covers and an unmemorable original composition and they were finished. I thought that Bonehead was a truly brilliant musician and I was also impressed by the fact he could play while completely smashed out of his face. I knew that I would add something different to the group’s sound, so afterwards I agreed to join the cause and rehearsals were arranged for the following week.

The practices initially took place in Huts’s garage in Burnage. The set slowly evolved. As well as the standard cover, ‘Wild Thing’ by the Troggs, we also developed six or seven original compositions that were penned by Bonehead and Huts. As the weeks passed, we grew as a group. It was a good feeling.

Somebody mentioned a hotel not far away and a receptionist who I’ll call Caroline – not her real name. It seemed they were both very happy to have the band in them. A rehearsal room was secured immediately. The hotel was an unusual place: a magnificent Victorian building sat back proudly on the leafy tree-lined road, but it ran on a skeleton staff. We rehearsed there for nearly a year, yet never saw more than a handful of guests. Not that we were complaining. A generous receptionist and a regularly unmanned bar led to free love and free alcohol. When we weren’t rehearsing in the basements we would be leapfrogging the bar upstairs. Musically, we tightened the set we already had, but there were no more creative moments. After a few months, and minus a drum machine, we felt ready to unveil a less programmable version of the band upon south Manchester. Our first couple of gigs were pretty impressive and the compliments were good. We also had the usual ‘never heard anything like you before’ line, though I guess that may not necessarily have been a compliment…

Buoyed up, we decided that The Rain were going to make something of their efforts after all, and as a result we started gigging more. We also arranged for demos to be sent out to record companies and the local media, as all bands do. No fucking replies. It didn’t stop us, though, as we had the spirit and attitude that was running through the Roses and the Mondays, who were then at their height. Unfortunately, that same spirit and attitude had also mobilised a thousand other young bands, so competition was tough.

We decided to approach Anthony H. Wilson, the founder of Factory Records and also a local television presenter. The problem was that Mr Wilson fell on The List. Let me explain about The List. Manchester is a unique city in the way it judges and treats its celebrities. If you are considered to be what is locally known ‘as up your own arse’, you are put on The List. If the locals might happen to discover a ‘weakness’, which could be something as minor as hair colour or shoe choice, they would also put you on The List. At best, the qualification criteria were random. This contempt and attitude was everywhere, so there was plenty to go round as well. It was contempt bred by familiarity on the streets of Manchester. Everybody had an opinion and rather than adulate ‘celebrities’ they would front them. There was no divide. The bricklayer or football hooligan. The insurance clerk or the student. Everyone had the ‘Roses’ attitude. Anyone on The List that you encountered would be in for a barrage of abuse. Some friendly. Some not. On The List in 1990, alongside Mr Wilson, you could also find the likes of Mick Hucknall, Peter Hook and Terry Christian. It didn’t take much to get on it, but it was damn fucking difficult to get off. When they received a volley of abuse, different List members reacted in different ways. Peter Hook turned mute but one look at his hairy face would tell you how angry he was. Terry Christian laughed. Mick Hucknall scurried away.

Tony Wilson, though, would always turn and offer something equally as vicious back. His raincoat would flap wildly behind him as he would turn to leave, arm left hanging in the air, his middle finger giving some out. Tony was one person who, over time, eventually got himself off The List and instead demanded respect in those who had previously berated him on the streets of Manchester. And he certainly got it. I fell into that crowd. Anthony H. Wilson had a more radical view of the music industry than any of those around him. Just to have the notion that you could have a contract of trust with a band and then actually put it into practice was astounding. But that was Wilson all over. Astounding. The group of corporate types who, at one point, were interested in buying Factory must have stood with their mouths open wide as Mr Wilson explained that his record company had not a single binding contract with any of its artists. This was after he had invited the corporates round to buy the failing record company. Not surprisingly, they didn’t.

Anyway, we drove round to his house in Didsbury, hoping he didn’t recognise any of us from the street abuse. I reckon he did. Guigs knocked on the door. Tony Wilson himself opened it. The boot was most definitely on the other foot, as he brushed us away with advice to send the demo tape to the office. Can’t say we weren’t trying, but we just needed that break. So we cracked on with the gigs.

‘JD and coke, please.’ This had become my drink of choice. It still is. It sounded more rock ’n’ roll than half a bitter. I had just finished setting up my kit on stage at the Times Square pub in Didsbury, Manchester, and was watching as the boozer filled. It was a strange mixture of old regulars, the new annual influx of students, and the usual crowd of family and friends who now followed us. Manchester was that year’s most requested university, breaking the stranglehold of Oxford and Cambridge for the first time. We had all cheered the news. It meant more women in the city. There was an element of Me Man You Student about the locals’ approach to courting at that time.

Suddenly, the door opened and young Liam swaggered in. As usual, heads turned at the sight and sound of him. He walked in front of BigUn, talking very loudly over his shoulder to his large friend behind. Typical Liam. Always wanted the spotlight. BigUn laughed loudly at what Liam was saying. He might have been nicknamed BigUn, but he was no lumbering Lenny. This man was as sharp as they come, and let’s just say self-confidence was never an issue. He was a Levenshulme lad of the West Point variety who was always capable of creating trouble in situations where no one else possibly could. As a relationship, Liam and BigUn were a strange combination, but one that would provide endless laughter and adventure.

I was standing at the bar when Liam spotted me. ‘Have a fucking good one tonight, Tony,’ he shouted, over Northside’s ‘Shall We Take a Trip’. I smiled back and asked him if he wanted a drink. He shook his head and said he couldn’t buy me one back. Broke. I bought him and BigUn one anyway and they both marched off to find a suitable seat.

Guigs was already on stage and was looking nervous. Back then, he had taken to smoking a field’s worth of weed before each performance, which helped his nerves. This wasn’t always good news to the drummer, who relied heavily on the bass to keep time himself. Bonehead had already downed a small vineyard and Chris was having an ‘artistic’ moment. ‘I’ve changed some of the lines in “Wild Thing”, so just go with me,’ he shouted to us over the music, once we were into our set. His lyrical rewrite? ‘Wild Thing, I think I love you. Let’s go and smoke some draw.’

I shook my head in disbelief as we finished that song and moved onto our topical tribute to the Strangeways Riots. ‘We’re Having a Rave on the Roof’ was in full swing as I became distracted by Liam and BigUn at the side of the stage, arguing with two large, red-faced men who had accused them of stealing their pints. After a few heated words, and I’m sure physical threats, the accusers made off, leaving Liam and BigUn to smile and raise their stolen pints in my direction. Some fucking babies, I thought.

After more rehearsals in the garage, we played The Boardwalk twice, but although we sold it out I couldn’t help noticing it was mainly family and friends, and friends of friends. The support was welcomed, but we weren’t exactly setting the world alight. We had been together for over a year by this stage and our initial enthusiasm was beginning to wear thin. We got on well as a group of people and had become tight-knit as a band, but Guigs wasn’t happy.

‘Huts isn’t doing enough to be a lead singer,’ he said. Now, I liked Huts. He was a Spartan and you knew where you stood with him. I wondered just what Huts’s review of Guigs’s bass-playing might be. But to be fair, Guigs did have a point. Something just wasn’t right. I wasn’t sure if it was Huts or not, but something wasn’t working. It was decided that after an exhausting six gigs, we should take a breather. Spend some time apart. You know, clear our heads. It was obvious that Guigs had ideas about replacing Huts that didn’t sit well with me. I’d never been any good at skullduggery. I had always believed in being upfront and honest. I tried to plead a case for the singer.

‘We should speak with him, at least. He’s one of us.’ Bonehead had wedged himself firmly on the fence, which would become his resident position, while Guigs said we should go away and think about it. So we decided to take a few weeks out and see what time would bring. I couldn’t help thinking, though, that maybe I had only delayed the inevitable.

My suspicions proved correct. Time would bring a fascinating revelation for me, and a slap in the face for Huts.

‘We’ve got someone who wants to join as the lead singer.’ An excited Bonehead was on the phone.

‘Oh yeah? Who?’ I replied.

Out of the handset came: ‘Liam. Liam Gallagher.’

It seemed that BigUn had been mentoring Liam and had advised him he had the makings of a great frontman. As BigUn was aware that Huts was living on borrowed time, he had put Liam in touch with Bonehead. I had a silent chuckle to myself. I thought about Liam as the face of the band. He definitely looked the part. But what about the aggravation? He was a right handful. Fuck it. If we were gonna be a rock ’n’ roll band, that was exactly what we needed. Although Liam had started to style himself on Ian Brown, with his haircut and swagger, he could never be accused of not being his own man. I’d last seen Liam at a Roses concert and the aggressive, cheeky yet lovable boy had transformed into an aggressive, cheeky yet lovable young man. If you needed front to get by in the music business, Liam had enough to cover the country. Something tells me we’re into something good.

‘Has anyone told Huts?’ I asked.

‘Guigs is gonna do it,’ replied Bonehead. I thought to myself that that conversation wouldn’t happen in a hurry. In the end, I took the time to let Huts know exactly what was going on, because no one else did. Understandably, he was very unhappy and couldn’t see where it had gone wrong.

‘It hadn’t,’ I told him and expected the whole band thing to come to a halt there and then. I thought it was the end, yet funnily enough it was only the beginning.

We’d arranged for Liam to come and audition at my place on Ryton Avenue in Gorton, on a summer’s day in 1991. The audition panel would consist of myself, Bonehead and Gemma, my one-year-old daughter. We were sitting eagerly in my front room, waiting. Liam normally entered a room like a storm. He’d be blowing insults and compliments, throwing out opinions and judgements. It was just humour and a little insecurity, though, nothing dangerous. As I already knew him, I had given both Bonehead and Guigs a rundown; they had both seemed impressed. Bonehead walked through the door, his eyes red and still slightly askew from the previous night’s exertions. Then a rather nervous-looking kid appeared – Liam – but shit, he looked the part. Pair of brown cords ripped at the knee with a denim shirt loosely flowing. Desert boots and smart haircut. Liam had a talent for wearing clothes from Debenhams and still actually looking cool. I waited for the verbal onslaught. But it seemed the belligerent attitude had been left behind in Burnage. He stood rather sheepishly at the living-room door. Then, all of a sudden, he jerked forwards into the room as BigUn put his hand in the small of his back and pushed firmly.

‘Let’s get this fuckin’ show on the road,’ BigUn said, with a smile in his voice. He stood there, rubbing his hands together, as Liam threw a playful punch at him. I had warmed to BigUn. There was a spark about him. Never one to settle for his allocated lot, he was always on the lookout for an opportunity or opening. And he had a big heart.

A successful audition was guaranteed from the start, I suppose. The way I figured it, we hadn’t got anyone else. Bonehead hadn’t brought a rhythm guitar, so picked up a battered, out-of-tune bass I had lying in the back room. My drum kit was at the rehearsal room, so I made do with a set of bongos. Me and Bonehead started to bang out some old tune that was unrecognisable to us, never mind Liam. In turn, Liam hummed a tune that was also completely unrecognisable to us. During all this, BigUn danced from foot to foot, displaying all the rhythm of a rusty robot. It had to go down as one of the most unprepared, unprofessional and useless auditions ever. But then again, we finished with one Liam Gallagher as our frontman. So maybe it was the best.

After a few rehearsals, in which Liam introduced some songs that he had been working on, we started to get a feel. It was strange at first with Huts not being up front, but we all recognised the fact that Liam had something about him. It might have been menacing and slightly evil, but it was still ‘something’.

We had all now decided that we were going to ‘knock fuck out of anything in our way’. This mission statement wasn’t exactly hung on the rehearsal room wall, but we all understood and suddenly the confidence started to show in our performances. We were still rehearsing at the hotel, although we had been warned that we would have to be gone soon. It seemed the money pit had been sold and was soon to be demolished. When the time came for this move, we temporarily took up residency in The Grove in Longsight. This was a snooker hall turned Irish club, the same kind our parents had visited a generation before, though the frilled shirts had now been replaced by cowboy-style equivalents. Paul Gallagher had ‘sorted out’ our tenancy with the owner. We were never quite sure of the terms; we just gave the cash straight to Paul. This was where we would finally gel and begin to feel like a real act. Rehearsals had once again turned into an alcoholic free-for-all, with the bar being raided regularly. BigUn would be on lights and the PA desk and our rhythm section really started to come together; gradually, we began to create our own distinctive sound. Unfortunately, although we really enjoyed our time there, the discovery of our alcohol theft led to us being told to move on. From The Grove we headed to The Greenhouse Rooms in Stockport. This was a purpose-built rehearsal studio and had its own backline (gear, amps etc.). We were developing original material now; ‘Life in Vain’, ‘Reminisce’, ‘She Always Came Up Smiling’ and ‘Take Me’ were the stand-out tracks. Lyrically, these songs were a collaboration between Liam and Bonehead. Guigs’s bass playing was still basic, but he was steadily improving and the rhythm section of the band had developed quite a unique sound. And then there was the way Liam delivered the songs. The rest of us almost seemed to fade into the background; all our audiences seemed to be transfixed by our lead singer. Even at rehearsals. His nasal delivery and fighting stare would leave people enthralled and threatened, both impressed and nervous.

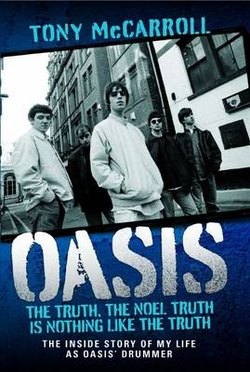

From the start, I didn’t think Liam was happy with the name The Rain. I guessed as much when he said, in one long breath: ‘It’s a dogshit name. Any ideas, anyone? No? Right, we’ll call ourselves Oasis.’ The whole dynamic of the group had changed with him joining. Why not the name? It later transpired that BigUn had spotted the name on an Inspiral Carpets poster hanging on Liam’s bedroom wall the previous evening. It sounded good to me.

And so Oasis the band was born. We rehearsed and rehearsed for the next eight months or so, during which time we all got to know Bonehead better. Most of his friends we already knew through BigUn and this was when the Entourage was formed, a group of mates and acquaintances who would provide us with back up and support.

The band would always maintain a positive spirit and quickly developed an ‘us against the world’ kind of attitude. We knew that we had a distinct sound as a rhythm section and everyone in the band thought that Liam had the charisma and natural personality to take it somewhere. Everyone except Liam, that is. He wanted to invite his brother Noel to join the group. Liam had already played a demo of Noel in a band called Fantasy Chicken and the Amateurs to us. In truth, it was not very impressive, but he did know a lot of people in the industry so we put him on a back burner.