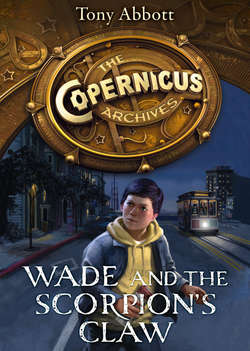

Читать книгу Wade and the Scorpion’s Claw - Tony Abbott, Tony Abbott - Страница 10

Оглавление

The jet was packed. The attendant at the desk told my dad that the flight had been overbooked and that one of our five seats wasn’t with the others. The loner was three rows back, which I said I would take, but Dad wanted us all together.

The man with the green shoulder bag was in the window seat across from our other seats. He already had a blanket draped over him and sat leaning against the window.

When another passenger—the long-haired acrobat guy who’d stood on his hand for the baby—came in, heading for the open aisle seat, Dad asked if he’d mind switching with me.

“Or are you two together?” Dad asked him.

“No, no.” The acrobat glanced at the man by the window, then at me, and smiled. “Not at all. Please, son, sit here.”

So after we were settled, Darrell and I were split by the aisle. He only took his seat—he was the last one to sit before the cabin door closed—after making sure Leathercoat wasn’t on our flight. “I didn’t see him. But if he works for Galina, he’s too good to be seen.” Which didn’t make any real sense, and didn’t slow my pounding heart, either.

As the jet taxied from the gate to the runway, the man with the green bag turned to me. “I am Dominic Chen,” he said, extending his right hand.

His fingers were ice-cold. “Wade Kaplan,” I said.

“I like to sleep on overnight flights,” he said with a slender smile, “but the protocol with fellow passengers is to chat, so we can, if you like.”

Protocol.

A week ago, protocol was just a school vocabulary word. But since Uncle Henry’s death had set off the secret Frombork Protocol—a set of instructions for the Guardians to gather the relics and destroy them—the word had taken on a whole new meaning. Maybe Mr. Chen’s use of protocol was just a coincidence.

Coincidence. Another word that sounded an alarm.

“That’s okay,” I said. “I like to rest, too.”

He nodded. “When we awake, it will be Sunday morning, the first day of a brand-new week. Enjoy your sleep.”

There was something soothing about Mr. Chen’s voice. Within minutes of hearing it, and the droning engines, I began to feel drowsy. I glanced at Darrell, the girls, and my dad. Their eyes were closed. We’d all gone a long time without any kind of rest, so that was good.

I closed my eyes, too. I wanted to go back to the dream of the cave, if only to get a better ending to it, but returning to a dream is nearly impossible when you try to force it. It didn’t work. Soon enough I stopped hearing noises and fell sound asleep.

I dreamed of nothing this time. Black space. No sound.

A few hours later, I woke up to bad news.

“… affects passengers with destinations in New York,” the pilot was saying. “A real kahuna of a snowstorm is flying up the East Coast and has shut down all three New York airports.”

Lots of passengers groaned, so we weren’t alone.

“Are you kidding me?” Darrell’s hair was going in every direction. He was obviously still groggy, but he had the ability to be groggy and jumpy at the same time. “We’re finally on our way, then everything stops? I can’t take this!” He slammed both fists onto his thighs.

“Don’t self-punch,” I said.

“But come on—”

“I get it,” I said. “Two steps forward, one step back.” I glanced at Dad, who leaned over and said something quietly. Darrell wiped his eyes and mumbled a couple of words, but shook his head sharply.

Soon there was a flurry of additional announcements.

“We’ll arrive a half hour ahead of schedule … it’s raining in San Francisco … airport hotel for stranded passengers …”

Blah blah blah. Landing early was normally good, except this time it meant that we’d spend an extra half hour in rainy San Francisco before we could get to New York and start our real search for Sara.

My ears popped as the jet descended. Mr. Chen was still wrapped up in his blanket, eyes closed, face turned to the window. Even with the clouds, the shade next to him was brightening with daylight. I wanted to raise it to see the city as we landed, like we were getting somewhere, but I didn’t want to bother him.

The landing gear rumbled welcomingly beneath the floor. As we drew closer to the airport, the pilot said his final words to the flight crew to prepare for landing. I tapped Mr. Chen’s shoulder lightly.

“Excuse me, Mr. Chen, we’re landing. If you’re going to New York, there’s a snowstorm.” I waited for him to rustle his blanket, blink, turn to face me sleepily. But he didn’t move.

We were asked to shift our seat backs upright. Because Mr. Chen remained sleeping, a passing flight attendant pressed the button on the arm of his seat to push his seat back gently forward. As she moved down the aisle, the blanket over his shoulders rolled down a few inches, and my blood turned to ice.

In the folds of Mr. Chen’s neck were several dark bruises.

“Mr. Chen?” I whispered. “Mr. Chen?” My throat seized. I could barely make a sound. I leaned across the aisle. “Dad,” I croaked. “Dad!” I glanced back to make sure I had seen what I thought I had.

There was no doubt. The angle of his neck and the purple marks on his skin meant only one thing.

I was sitting next to a dead man.