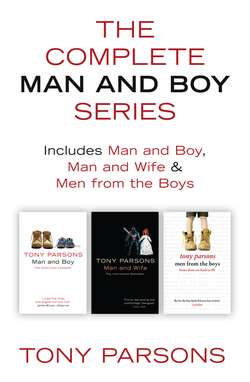

Читать книгу The Complete Man and Boy Trilogy: Man and Boy, Man and Wife, Men From the Boys - Tony Parsons - Страница 38

Twenty-Seven

ОглавлениеIt was more than the reminder of another man’s fuck.

If living alone with Pat had taught me anything, it was that being a parent is mostly intuitive – we make it up as we go along. Nobody teaches you how to do it. You learn on the job.

When I was a kid I thought that my parents had some secret knowledge about how to keep me in line and bring me up right. I thought that there was some great master plan to make me eat my vegetables and go to my room when I was told. But I was wrong. I knew now that they were doing what every parent in the world does. Just winging it.

If Pat wanted to watch Return of the Jedi at four in the morning or listen to Puff Daddy at midnight, then I didn’t have to think about it – I could just pull the plug and send him back to bed.

And if he was down after a phone call from Gina or because of something that had happened at school, I could take him in my arms and give him a cuddle. When it’s your own flesh and blood, you don’t have to think about doing the right thing. You don’t have to think at all. You just do it.

But I would never have that luxury with Peggy.

She was on the sofa, her little bare legs stretched out on the coffee table, watching her favourite Australian soap.

I was sitting next to her, trying to shut out the background babble of dysfunctional surfers who didn’t know the true identity of their parents, as I read an article about another bank collapsing in Japan. It looked like complete chaos over there.

‘What do you mean – you’re not my mother?’ somebody said on screen, and Peggy began to stir as the theme music began.

Usually she was off and running the moment the Aussies were gone. But now she stayed right where she was, leaning forward across the coffee table and picking up Cyd’s nail polish from among the jumble of magazines and toys. I watched her as she began to unscrew the top of the small glass vial.

‘Peggy?’

‘What?’

‘Maybe you shouldn’t play with that, darling.’

‘It’s okay, Harry. Mommy lets me.’

She removed the lid with the small brush on and, very delicately, began painting crimson nail polish over her tiny, almost non-existent toenails and, I couldn’t help noticing, all over the tips of her toes.

‘Be careful with that stuff, Peggy. It’s not for playing with, okay?’

She shot me a look.

‘Mommy lets me do this.’

Globs of bright red nail polish slid down toes the size of half a matchstick. She soon looked as though she had been treading grapes or wading through an abattoir. She lifted her foot, admiring her handiwork, and a drizzle of red paint plopped on to a copy of Red.

With Pat I would have raised my voice or grabbed the nail polish or sent him to his room. I would have done something. With Peggy, I didn’t know what to do. I certainly couldn’t touch her. I certainly couldn’t raise my voice.

‘Peggy.’

‘What, Harry?’

I really wanted her to do the right thing and not get nail polish all over her feet and the carpet and the coffee table and the magazines. But, far more than all of this, I wanted her to like me. So I sat there watching her small feet turning bright red, making doubtful noises, doing nothing.

Cyd came out of the bathroom wrapped in a white robe, towelling her hair. She saw Peggy daubing her toes with nail polish and sighed.

‘How many times have I told you to leave that stuff alone?’ she asked, snatching away the nail polish. She lifted Peggy like a cat plucking up a unruly kitten. ‘Come on, miss. In the bath.’

‘But – ’

‘Now.’

What made me laugh – or rather what made me want to bury my face in my hands – is that you would never guess that so much of our time was spent dealing with the fall-out of the nuclear family. Cyd’s small flat was like a temple to romance.

The walls were covered with posters from films – films that told tales of perfect love, love that might bang its head against a few obstacles now and again, but love that was ultimately without any of the complications of the modern world.

As soon as you had come into the flat, there was a framed poster of Casablanca in the poky little hallway. There were framed posters of An Affair to Remember and Brief Encounter in the slightly less poky living room. And of course there was Gone with the Wind in the place of honour right above the bed. Even Peggy had a poster of Pocahontas on her wall looking down on all her old Ken and Barbie dolls and Spice Girls merchandise. Everywhere you looked – men smouldering, women melting and true love conquering.

These posters weren’t stuck up in the way that a student might stick them up – half-hearted and thoughtless and mostly to cover a patch of rising damp or some crumbling plaster. There was far more than Blu-tack keeping them up. Placed behind glass and encased in tasteful black frames, they were treated like works of art – which I suppose is what they were.

Cyd had bought those posters from one of those cine-head shops in Soho, taken them to the Frame Factory or somewhere similar, and then lugged them all the way home. She had to go out of her way to have those posters of Gone with the Wind and the rest up on her walls. The message was clear – this is what we are about in this place.

But it wasn’t what we were about, not really. Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman might have had their love affair cut short by the Nazi invasion of Paris, but at least Bogey didn’t have to worry about how he should treat Ingrid’s child from her relationship with Victor Laszlo. And it is open to debate if Rhett Butler would have been quite so keen on Scarlett O’Hara if she had been dragging a kid from a previous romance around Georgia.

I had never been around a little girl before, and there was an air of calm about Peggy – it was definitely calm more than sugar and spice or any of that stuff – that I had never seen in Pat or other small boys. There was a composure about her that you wouldn’t see in a boy of the same age. Maybe all little girls are like that. Maybe it was just Peggy.

What I am saying is – I liked her.

But I didn’t know if I was meant to be her friend or her father, if I was meant to be sweetness and light or firm but fair. None of it felt right. When your partner has got a child, it can never be like the movies. And anyone who can’t see that has watched a few too many MGM musicals.

Cyd came back into the room with Peggy all clean and changed and ready for her big night out at Pizza Express with her father. The little girl climbed on my lap and gave me a kiss. She smelled of soap and Junior Timotei.

Her mother ruffled my hair.

‘What are you thinking about?’ she asked me.

‘Nothing,’ I said.

Peggy’s eyes got big and wide with excitement when she heard the sound of a powerful motorbike pulling up in the street.

‘Daddy!’ she said, scrambling from my lap, and I felt a stab of jealousy that caught me by surprise.

From the window we all watched Jim Mason park the big BMW bike, swinging his legs off as if he were dismounting from a horse. Then he removed his helmet and I saw that Cyd had been right – he was a good-looking bastard, all chiselled jawline and short, thick wavy hair, like the face on a Roman coin or a male model who likes girls.

I had always kind of hoped that there was going to be something of Glenn about him – a fading pretty boy whose years of breaking hearts had come and gone. But this one looked as though he still ate all his greens.

He waved up at us. We waved back.

Meeting your partner’s ex should be awkward and embarrassing. You know the most intimate details of their life and yet you have never met them. You know they did bad things because you have been told all about them and also because, if they hadn’t done bad things, you would not be with your partner.

It should be a bumpy ride meeting the man she knew before she knew you. But meeting Jim wasn’t that much of a problem for me. I got off lightly as there was still so much unfinished business between him and Cyd.

He came into the little flat, big and handsome, all gleaming leathers and wide white smile, tickling his daughter until she howled. We shook hands and swapped some small talk about the problems of parking in this neck of the woods. And when Peggy went to collect her things, Cyd was waiting for him, her face as impassive as a clenched fist.

‘How’s Mem?’ she asked.

‘She’s fine. Sends her love.’

‘I’m sure she doesn’t. But thanks anyway. And is her job going well?’

‘Very well, thanks.’

‘Business is booming for strippers, is it?’

‘She’s not a stripper.’

‘She’s not?’

‘She’s a lap dancer.’

‘My apologies.’

Jim looked at me with a what-can-you-do? grin.

‘She always does this,’ he said, as if we had some kind of relationship, as if he could tell me a thing or two.

Peggy came back carrying a child-sized motorbike helmet, smiling from ear to ear, anxious to get going. She kissed her mother and me and took her father’s hand.

From the window we watched Jim carefully place his daughter on the bike and cover her head with the helmet. Sliding behind her, he straddled the machine, kicked it into life and took off down the narrow street. Above the throaty roar of the bike, you could just about hear Peggy squealing with delight.

‘Why do you hate him so much, Cyd?’

She thought about it for a moment.

‘I think it’s because of the way he ended it,’ she said. ‘He was home from work – hurt his leg in another accident, I think he was scraped by a cab, he was always getting scraped by a cab – and he was lying on the sofa when I got back from dropping Peggy off at her nursery school. I bent over him – just to look at his face, because I always liked looking at his face – and he said the name of a girl. Right out loud. The name of this Malaysian girl he was sleeping with. The one he left me for.’

‘He was talking in his sleep?’

‘No,’ she said. ‘He was pretending to talk in his sleep. He knew he was going to leave me and Peggy already. But he didn’t have the guts to look me in the eye and tell me. Pretending to talk in his sleep – pretending to say her name while he was sleeping – was the only way he could do it. The only way he could drop the bomb. The only way he could tell me that his bags were packed. And that just seemed so cruel, so gutless – and so typical.’

I had different reasons for hating Jim – some of them noble, some of them pitiful. I hated him because he had hurt Cyd so badly, and I hated him because he was better looking than me. I hated him because I hated any parent who breezed in and out of a kid’s life as though they were a hobby you could pick up and put down when you felt like it. Did I think that Gina was like that? Sometimes, on those odd days when she didn’t phone Pat, and I knew – just knew – that she was somewhere with Richard.

And I hated Jim because I could feel that he still mattered to Cyd – when she had said that thing about always loving his face, I knew it was still there, eating her up. Maybe she didn’t love him, maybe all that had curdled and changed into something else. But he mattered.

I suppose a little piece of my heart should have been grateful. If he had been a loyal, loving husband who knew how to keep his leather trousers on – and if he wasn’t into the bamboo – then Cyd would be with him and not me. But I wasn’t grateful at all.

As soon as he brought Peggy back safely from Pizza Express, I would have been quite happy for him to wrap his bike around a number 73 bus and get his lovely face smeared all over the Essex Road. He had treated Cyd as if she were nothing much at all. And that was reason enough for me to hate his guts.

But when Peggy came back home with a phenomenally useless stuffed toy the size of a refrigerator, and pizza all over her face, I was aware that there was another, far more selfish reason for hating him.

Without ever really trying to match him, I knew that I could never mean as much in Peggy’s life as he did. That’s what hurt most of all. Even if he saw her only when he felt like it, and fucked off somewhere else when he felt like doing that, he would always be her father.

That’s what made her giddy with joy. Not the motorbike. Or the pizza. Or the stupid stuffed toy the size of a fridge. But the fact that this was her dad.

I knew I could live with the reminder of another man’s fuck. I could even love her. And I could compete with a motorbike and a giant stuffed toy and a prettier face than my own.

But you can’t compete with blood.