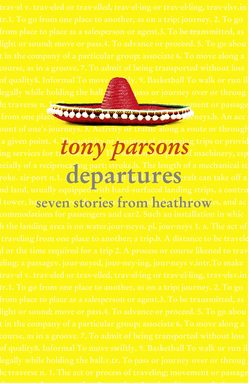

Читать книгу Departures: Seven Stories from Heathrow - Tony Parsons - Страница 5

ОглавлениеChapter One

The Green Plane

She was not a weak woman.

As she stood at the window, watching the pale blue sky and looking back on her twenty-nine years of life, Zoe could see no evidence that she was weak, timid, or what her three elder brothers would have sneeringly called a ‘wuss’.

When a girl grows up heavily outnumbered by brothers, Zoe thought, she learns to take the knocks, and never to let them see you cry, and always to be tougher than they expect.

Zoe had done all of that, and then when her brothers were all grown and gone and getting on with their lives, and she could have relaxed a little bit on the whole acting tough thing, she had spent a gap year wandering Asia alone (her best friend was meant to come but she met a boy – it was that old story). Zoe had ridden a prehistoric rented motorbike from Hanoi to Ho Chi Minh City, shivered with dysentery in Mumbai, and when the money ran out – Japan had been more expensive than she was anticipating – she had slept rough in a park in Kyoto while waiting for her parents to send her the fare to come home.

I am not weak, she thought, so vehemently that she almost said it out loud. I’m not, I’m not, I’m not.

But, as she stared at the sky, a small black line appeared against the perfect blue, as thin as a razor cut, and she felt her breath shorten and the sweat break out and the panic fly.

It moved so slowly. Though the plane must have been going at, what – 500 mph or so? – it seemed to move in slow motion as it crossed the London skyline, and then languidly turned, as if ready to meet its fate.

Zoe was not a woman who scared easily.

But Zoe was afraid of flying.

‘Angel?’

She turned from the window to look at her husband. He was sitting at the kitchen table, their three-year-old girl on his knees, attempting to keep her sticky little fingers away from the laptop in front of him.

‘It says here,’ he said, ‘that twenty-five per cent of people have some fear of flying and around ten per cent have a real psychological phobia.’

‘But I’m not afraid of flying,’ Zoe insisted.

In the silence her husband, Nick, and their daughter, Sky, smiled at her sympathetically, as if forgiving her this blatant lie.

Nick returned to the computer. Sky banged her small hands on the keyboard as if it was a toy piano. Nick gathered both of the child’s hands in one of his own, and pointed at the screen with an enthusiastic grin that somehow made Zoe’s spirits sink.

‘They do courses for people who, er, don’t like to fly,’ he said. ‘British Airways had a course called Fear of Flying – please don’t do that, darling’ (this to his daughter) ‘– and now they call it, um, Flying With Confidence.’

Zoe laughed bitterly. ‘That’s a smart move. Flying With Confidence sounds a lot more positive than Fear of bloody Flying.’

Nick looked hurt. ‘But that’s a good thing, isn’t it? To be positive about the . . . aversion.’

‘They make it sound irrational,’ she said. ‘You make it sound irrational. All those hundreds of people locked inside a metal tube above the clouds. Maybe it’s you that’s crazy for not being . . . a little bit . . . worried? You ever think about that, Nick? Maybe it’s you and the rest of the flying glee club. Maybe I’m the sane one.’

She turned back to the window. There were a few of them up there now – their west London home was directly under a flight path – moving like deep black wounds in the sky. So slowly, so slowly. As if they could fall at any moment. She wiped her hands on her jeans, and it all came back.

The noises that sounded like the end of everything. The engines starting – that screaming sound that froze the blood. The suicidal dash to the end of the runway. The mad sensation of leaving solid ground. Rising, rising, like the nausea in the pit of your stomach. And then – perhaps worst of all – the sound of the undercarriage being lifted, as final as the lid on your coffin slamming shut and the nails being banged in. That was the moment you knew there was no going back.

You were trapped.

Then Nick was by her side, Sky in his arms. The girl slipped from the arms of her father to her mother, the way monkeys and small children do.

‘I just want to help,’ Nick said.

She put her free arm around him.

‘I know you do,’ she said. ‘But the thing is, Nick – I really don’t have a fear of flying.’

He looked uncertain. ‘You don’t?’

‘It’s just that I have a problem with take-off and landing,’ she said. Then paused. ‘And the bit in the middle.’

‘One of these courses can help,’ he said. ‘I believe it. There are lots of people who feel like you, Zoe. You’re right – it’s not a mad way to feel. On these courses, pilots talk to you. They explain the sounds. I know you don’t like the sounds . . .’

She suddenly lit up.

‘Or we could do something else,’ she said excitedly.

‘Yes?’

‘Stay home,’ she said, jiggling the child in her arms, making her laugh, and smiling herself now. ‘We could just stay home, Nick. Not go.’

Nick stared at his wife for a long moment.

And then he shook his head.

‘But we have to go,’ he said.

The green plane burned.

The engine burned. The cockpit burned. The green plane burned in the galley and it burned in the undercarriage and it burned in the brakes.

The green plane burned more wildly as the firefighters jumped from the two fire engines – rigs, they called them, and they did not look like anyone’s idea of a fire engine. These fire engines, these rigs, looked more solid, more tank-like, and more ready for a war than a normal fire engine. They were built to go in a straight line. From one of two fire stations at either end of Heathrow to an aircraft in trouble. Like the green plane.

An oil spill spread quickly under the two sawn-off wings of the green plane, and that burned too, a sheet of fire that swiftly rose to a spectacular wall of flame, trailing black smoke as the four firefighters advanced towards it, crouching before the terrible heat, tasting it in the back of their throats, the hoses in their hands looking like small, ineffectual weapons, plastic swords against a dragon, until the moment they began covering the fire with foam, starving it of the air that it craved, choking it, killing it.

In one of the two rigs that faced the nose of the green plane, unloading their blankets of foam on top of the fire, Fire Officer Mike Truman watched the proceedings with quiet satisfaction.

Mike had watched Heathrow’s green plane burn hundreds of times. It was a strange-looking hybrid, made up of many aircraft. The tail of a DC-10. The fuselage of a Jumbo. Bits and pieces all combined into one so that the Heathrow Airport fire service could be prepared for any fire on any aircraft at any time.

Burning the green plane was a drill. Aircraft use Jet A-1 aviation fuel, a hydrocarbon fuel, whereas the green plane’s fires were gas. And aircraft are constructed of sheet aluminium, or more recently lightweight plastics reinforced with man-made mineral fibres known as composites, and the green plane was built of steel. It was just a drill. But there were twenty-six different scenarios on the green plane – twenty-six different ways for it to burn. So it was a drill that prepared the firefighters of Heathrow for anything.

When the green plane had arrived at the airport at the end of the last century, the same year as Mike, it had been as immaculate as a brand-spanking new car fresh off the assembly line. The green had shone in those days, like a pair of Robin Hood’s freshly washed tights.

Now, after the countless fires that Mike and his firefighters had started, the green plane was definitely showing its age. There were scars. There was wear and tear. It looked a bit rough. Just like me, Mike thought, grinning to himself.

Then he looked at the sky and frowned.

A big, blue cloudless sky hung above Heathrow. It was a beautiful day, he reflected with distaste. And that, thought Mike Truman, was the only thing that stopped this being a perfect drill.

He liked to see the green plane burn when the weather was filthy. He liked it when the light was bad, and the rigs sprayed rain or slush from their wheels as they raced to an incident.

An aircraft, he always reminded his men, contains enough fuel to fill five oil tankers. Imagine – just imagine, he would tell them – what that lot looks like when it is on fire. An aircraft is an unexploded bomb with five hundred people sitting inside it. And our job is to keep them all safe from harm.

So you didn’t want good weather when you burned the green plane, Mike thought. You wanted one of those rubbish days. Because it might be a plane returning to the airport shortly after take-off, stuffed full of Jet A-1. Because it might be an aircraft with ice in the fuel tanks and its engine gone. Because it might have had a heavy landing and burst ten tyres on its undercarriage, or twenty. Because it could be on fire in one of twenty-six places. And because you had to be ready for anything.

Zoe, Nick and Sky came through security and went to the lounge.

There was a small play area for children. Sky busied herself banging some plastic bricks together while Nick examined the baggage tags on their boarding cards, and checked the passports, and consulted the departure screen for their gate number. And then did it all again.

Zoe swallowed hard. It was happening. It was really happening.

Beyond the high glass windows of the lounge, planes as big as ocean liners queued on the runway: Jumbos and 777s and Airbus 380s all waiting their turn to hurtle from the ground.

‘I’ll be right back,’ Zoe said, and caught the look of alarm on Nick’s face as she turned away and walked out of the lounge.

Near the door there were travellers who had just passed through security. They were collecting their bags, putting their belts on, stuffing keys and coins and phones back in their pockets, slipping laptops into travel bags, reclaiming their dignity and their shoes. Beyond the metal detectors and the security guards there were more people waiting patiently. And beyond a distant wall, Zoe knew, even though she couldn’t see her, there was the lady who had checked their passports and boarding cards and told Sky that she was adorable, just adorable.

The traffic is all one way, Zoe thought.

The traffic was all heading towards getting on those planes, as surely as every life heads towards a grave. There was no way out. No escape.

Zoe went to the toilet, aware that her breath was getting shorter.

Closing the door of the stall behind her, she closed the lid of the toilet, sat down and pulled a pack of cigarettes out of her bag. She hadn’t smoked for years, and was surprised to see how alarmist the health warnings had become. DIE, DIE, DIE, it said on the side of the packet. YOU ARE DEFINITELY GOING TO DIE. Or perhaps she was just imagining it.

She put one in her mouth, wondering what she should do next.

She struck a match.

She lit the cigarette.

Then Zoe puffed on it nervously, trying to ignore the wave of nausea as she thought how much she hated smoking.

Do I have to go? she asked herself. Do I really have to go? Even now, can they make me go?

If I explain . . .

And then the smoke alarm went off.

‘Go,’ Mike said, feeling his blood pump as the station’s tannoy reported an emergency.

And they went.

Mike led a responding team of five out to the rig. When they answered the call on the fire station’s tannoy, they knew nothing about what they were heading towards. It could be anything. And anything was what they trained for, what they steeled themselves for. It was only when they were in the rig and on their way that the airport’s central operations room, the Star Centre, filled them in.

There were codes used for certain emergencies. Terrorist activity. Physical assaults. But there was no code for this one.

‘Fire in departures, Terminal Five, ladies toilet adjacent to Gordon Ramsay’s. Terminal staff attending.’

Mike’s driver chuckled, but did not touch the brakes of the rig as they hurtled towards the terminal building. Even if it was next door to nothing, they still had to respond.

‘There will always be some idiot sneaking a smoke before they board,’ the driver said.

Mike watched the airport flash by, his face set in the hard lines of a man who is trained to risk his life for strangers, and he found that he could not smile with the others.

As if in a dream, the firefighter appeared before Zoe in full firefighting regalia.

He wore a bulky-looking blue suit with flashes of silver and yellow on the jacket and trousers. He had a bright yellow helmet and heavy rubber black boots. He had a sort of utility belt around his waist, such as Batman might approve of, containing a bewildering array of tools. Zoe thought he was like a walking Swiss Army knife. Later, when she thought about the first sight of him standing outside the toilet door, in her imagination she could have sworn that he was carrying a hose. But that wasn’t possible, was it?

‘Hello,’ Mike said to Zoe. ‘Have you got a minute?’

‘I was scared,’ she said. ‘That’s all.’

‘But there’s no need to be scared,’ he said. Zoe followed Mike out of the toilet. There were four more firemen outside. People were looking and pointing at Zoe. But she saw that Mike was staring up at the Departures board. ‘Where you off to?’ he asked her.

‘Canada,’ Zoe said. ‘Toronto. The BA flight.’

Mike smiled. ‘You’ve got ages yet,’ he said. ‘You like getting to the airport early, don’t you?’

‘Not me,’ Zoe said. ‘That’s my husband. I would be happy to never get here.’

Then Nick and Sky were there, staring at Zoe and the fireman, and wondering what she had done.

‘Can you spare her for a while?’ Mike asked them.

Zoe rode back to the fire station with them.

On the way they passed the green plane, the fires all out now, and Zoe thought she was seeing things when she noticed that the perimeter of the training ground was covered in smashed cars. Every kind of car in every degree of destruction. Vans and trucks too. On their side and upside down. Smashed up and bashed up and trashed. Windows caved in and engines pulped and roofs flattened.

‘We cut them up,’ Mike explained, following her gaze. ‘To get the people out. And you see that green plane? We set fire to it in twenty-six different ways. That’s what we do most of the time.’ He glanced at her face. ‘Nothing bad is going to happen,’ he said. ‘I promise you. But if it ever does – we’re ready.’

Mike showed her around the fire station. The giant four- and six-wheel rigs. Rows of harnesses, helmets and hoses so infinitely long that they looked as though they could stretch around the world. He showed her all this with a kind of wild pride and she thought of a book she had read at school: Gatsby throwing his shirts on the bed to impress Daisy. Everyone was very friendly. Everything was spotless. It was a world of men waiting for something catastrophic to happen.

‘It’s very clean,’ she said.

Mike looked a bit embarrassed. ‘Friday is our wash-up day,’ he said. Today was a Friday. ‘Perhaps it’s not always quite so clean.’

They gave her a cup of tea with lots of sugar and Mike talked all the while, explaining how there are 110 firefighters at Heathrow, with 27 men on a watch – a twelve-hour shift – and four watches around the clock. One watch on days, one watch on nights, and two at home, resting.

‘Which watch are you?’ Zoe asked.

‘We’re green watch,’ said Mike.

‘Like the plane you set fire to,’ she noted.

‘Yes,’ he said, as though it had never occurred to him before, the way green watch was colour-coordinated with the green plane. ‘There’s something I want you to see,’ he said.

It was the tallest ladder in the world.

Mike called it an ALP – everything was an acronym with the men at the fire station, Zoe realized – and she had to get them to tell her twice that it was an Aerial Ladder Platform before she got it straight in her head.

Then one of the firefighters was helping her into an orange harness, and when that was comfortable she joined Mike on the metal platform of the ALP. He clipped them both to the rail of the platform and the thing, the ALP, began to rise.

It rose above the fire station.

It rose straight up and then it seemed to unfurl itself, and discover another ladder that had been hiding inside it, and rise even higher.

There were the runways down there, Zoe saw – two of them, she noticed for the first time – and there were the planes parked in their stands or taxiing to the runways or rising gracefully into the blue summer sky.

And then, impossibly, the ladder unfurled itself yet again and they were looking down on the roof of Terminal 5 and the Air Traffic Control tower was at eye-level. They were thirty metres high and still rising on a ladder that was far higher than any ladder on any fire engine in existence.

And for the first time she saw the secret city of the airport. She saw the secret city in all its calm glory, and its unruffled order, and the way everything worked and nothing bad happened. From up there on the fireman’s ladder, Zoe looked down at the airport, and she saw a safe world.

Mike was talking all the while. Zoe found that she could tune in and out and get the general gist of it.

‘There would be two of us up here and we would have one hundred metres of hose that can unload eleven thousand litres of water in four minutes,’ Mike said.

Zoe smiled. ‘That’s nice, Mike.’

They both looked at the airport. It looked like a place where nothing bad could ever happen. Even high in the sunlit calm, Zoe knew that wasn’t quite true. But she also knew that they were ready. And that she was ready too.

‘What’s in Toronto?’ Mike said.

‘My parents are out there,” Zoe said. “My father – he’s not very well. They say – the doctors – that he hasn’t got very long. And he’s never seen our daughter. So . . .’

She turned away so that he couldn’t see her face.

‘That’s no good,’ Mike said. ‘That’s rotten luck.’

‘It’s okay,’ Zoe said. ‘Or at least, it’s a lot better now.’

Just before their plane pierced the clouds a man in a window seat gave a strangled gasp.

‘A green plane!’ he said. ‘On the ground! I saw it! A green plane and it was on fire!’

Across the aisle, sitting calmly between her husband and her daughter, Zoe sipped her champagne and smiled to herself.

She felt the plane rise higher.