Читать книгу Bad Dad - David Walliams, Quentin Blake, Tony Ross - Страница 14

Оглавление

Escaping from the flat was something Frank had done many times before. Years ago Frank would sneak past his mum every Saturday night to watch his father race.

Back then it was easy. Frank would prop up his pillows on his bed under the duvet. That way if Mum bothered to get off the phone and poke her head round the door she would think her son was lying there fast asleep. Now there were no pillows, duvet or, indeed, bed.

Since the hard-faced men had come, the boy had slept on an old Lilo that always deflated during the night like a long, slow trump.

Frank had to come up with a new plan, and fast. If he was forced to listen to one more of Auntie Flip’s poems, there was a very real danger that he would spontaneously combust.

The boy made a life-sized dummy of himself by stuffing scrunched-up newspapers into some old pyjamas. Next he placed the dummy on top of his Lilo.

Finally, Frank had to pick his moment to make his escape out through the front door. From his bedroom he could hear that – surprise, surprise – Auntie Flip was composing a new poem in the living room. She was reciting it out loud as she wrote.

“O tall proud tree,

I see much of you in me,

Although I don’t have leaves

Or branches for that matter,

And I am not made of wood,

But other than that I could

Be a tree. And, oh yes, I don’t have bark…

“Oh dear, no, let me start again.

“O tall proud tree…”

The living room was at the end of the hall, so there was every chance Auntie Flip would see Frank if he tried to make a dash for the front door. After a short while, the boy could hear the lady shuffle down the corridor. This was his chance! Frank opened his bedroom door a tiny bit and put his eyeball up to the crack. Auntie Flip was closing the toilet door behind her.

“Oh no! The debt collectors have taken the loo seat too!” Frank heard her exclaim. “I will have to hover.”

There was no way of Frank knowing if it was a number one or a number two. How could he know? Such a thing was a private matter between Auntie Flip and Auntie Flip’s bottom.

A number two could take a long time (for some people hours, even days*) whereas a number one could be over in seconds. So Frank scuttled across the floorboards as quickly as he could (the hard-faced men had taken the carpet too) towards the front door. There he planned to wait for the noise of the flush to cover his escape.

DISASTER!

The toilet door opened again.

“I don’t believe it! No loo roll!” muttered Auntie Flip to herself.

Frank was crouched in the hallway, but scuttled back to his bedroom just in time. With her bloomers still round her ankles Auntie Flip scampered sideways like a crab back to the living room.

“Now, which poem can I sacrifice?” she asked herself. “They are all masterpieces. Let me see. Oh yes, can go!”

The boy then heard a page being torn out of a book.

Flip then scuttled back to the toilet and closed the door.

Frank crawled back to the front door and waited for the sound of the toilet flush.

Flip pulled the chain. But nothing happened.

Again. Nothing.

“Oh, goodness me! The chain’s snapped!” she exclaimed.

The boy then heard effort noises coming from behind the toilet door. “I’ll just have to hook my bloomers over the lever.”

Success!

Frank opened the front door, and shut it behind him as quietly as he could.

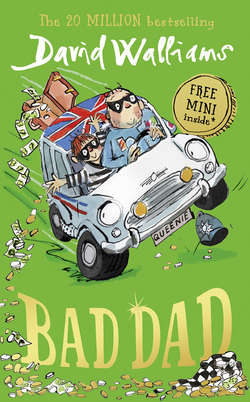

The lift was always broken in the block of flats, which was a pain when you lived on the ninety-ninth floor. Fortunately, Frank had devised a cool way of getting down the seemingly endless staircase. He’d found an old laundry basket, and with felt-tip pens had painted it with the colours of Queenie – red, white and blue. All he had to do was sit at the top of the staircase, and then let gravity take its course.