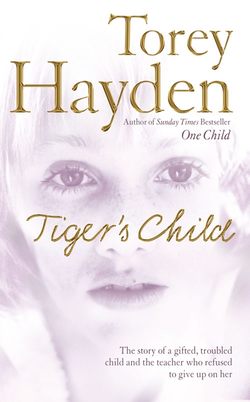

Читать книгу The Tiger’s Child: The story of a gifted, troubled child and the teacher who refused to give up on her - Torey Hayden, Torey Hayden - Страница 16

Chapter 9

Оглавление“God, did it really happen like this?” Sheila asked, a curiously amazed tone to her voice. It was the following Saturday. We were in her bedroom and she was curled up, the pages of the manuscript fanned out around her.

Smiling, I nodded.

“Wow, you were pretty brave to take me on, if I was like this.”

“A lot of people thought that at the time. I did a bit myself, sort of.”

“It wasn’t your choice, was it? They just said you got to take … me.” She looked back down at the sheaf of papers. “I think I might remember Anton now. I didn’t when you first mentioned him the other day, when we were at the Dairy Queen, but reading this kind of brings him back to mind.”

“You know what he’s doing now?” I asked. “He’s working on his master’s degree in special education. He works with mentally handicapped children and has had his own classroom for three years now.”

Sheila looked up. “God, you’re really proud of him, aren’t you? I can tell by your voice.”

“I think it’s amazing, what he’s achieved. That’s taken hard work. He’s had a young family to support through all of this and his whole history had been with the migrant workers.”

Regarding the typewritten pages, Sheila didn’t speak for a few moments. “All I can recall is this really tall Mexican guy. He seemed like about seven feet tall to me then, but I don’t remember a thing about what he did.”

“Do you remember Whitney?” I asked.

“No. But I do recall that time with the rabbit poop. I remember painting all those little balls. God, it’d disgust me now. Imagine. I was actually picking up shit with my bare hands.” She laughed. “What a disgusting kid.”

I laughed too.

“The weird thing is, you never think you are when it’s happening to you,” Sheila added. “I remember being really serious about painting those things.”

“What about Chad?” I asked. “My boyfriend, the one who defended you at the hearing? Remember him?” I asked, but before she could answer I grinned. “Guess what? He’s married now and he has three kids. And guess what he’s named his oldest girl?”

A blank look. “No idea.”

“Sheila.”

“After me?” she asked in amazement.

“Yes, after you. I mean, he thought the world of you. We had such a marvelous time that night after the hearing.”

A pause followed. Sheila glanced down again at the pages in her hand and appeared to be reading the top one for a moment. “Shit. Shit. This is just so weird. I can’t get over it.”

“Weird in what way?”

“I dunno. Seeing my name here. It’s somebody else here, really, but it’s me, too.”

“You don’t think I’ve done it right?” I asked.

“Well, no, not that … Maybe it’s just seeing myself as a character in a book … I mean, mega-weird.” Another pause. “You seem real enough. This is just like I remember you. Reading this makes me feel like I’ve been sitting down and having a nice chat with you, but … Was that class really this way?”

“How do you remember it?” I asked.

“Mostly, I don’t. Like I said last week …”

Silence again.

What entered my mind as I listened into the silence was the horrible nature of some of the things that had happened to Sheila over the course of the time she was in my room. In bringing the book here for her approval, I hadn’t given serious consideration to the possibility that she might have dealt with her past by forcing it from memory. Such a reaction seemed un-Sheila-like to me and I hadn’t anticipated it from her. Now, suddenly, I feared for what I had done. It was an upbeat story, but that was from my point of view.

Turning her head, Sheila gazed out the window beside her bed. It was an insignificant view—the side of the neighboring house, its gray-green paint peeling, the neighbor’s window, a venetian blind hanging crookedly across it. She seemed to study it.

I, in turn, studied her with her long, straggly orange hair, her thin, undeveloped body clad in torn jeans and a rather strange, clingy gray top that looked like a piece of my grandpa’s underwear. This gangly punk fashion plate wasn’t quite what I had expected to find and I was having to fight the disappointment.

“What I remember are the colors,” she said very softly, her tone introspective. “As if my whole life had been in black and white, and then I went in that classroom … Bright colors.” She made a little sound. “I always think of them as Fisher-Price colors, you know? The toys? Fisher-Price red and blue and white. All those primary colors. Remember that riding horse you could sit on and move around by pushing with your feet? That’s what I remember. Every single color of him. Of sitting at the table when I was supposed to be working and looking at his colors. And where it said ‘Fisher-Price’ on him. God, I wanted that horse so bad. I used to dream about that horse, about how it was mine, that you let me take it home and keep it.”

I probably would have, had she ever said it meant that much to her, but she never did.

“And that parking garage,” she said. “Remember that? With all those little cars that’d go down the ramps and those little people who didn’t even look like people. They were just plastic pegs with faces, really. Remember how I used to steal them? I was so desperate to have them. I used to line them up on the floor beside where I slept, this whole line of them—the guy in the black top hat, the guy in the cowboy hat, the Indian chief—do you remember me taking them?”

Over the years there had been so many toys in so many classrooms. I remembered garage sets and riding horses, but they could have been any of a dozen such I had had.

“You never got mad at me for it,” she said, turning to look at me. She smiled. “I kept stealing them and stealing them and you never got angry with me.”

In the hurly-burly of that class, truth was, I probably hadn’t even noticed she was doing it.

“That’s what seems so weird to me about this book, Torey. You make out like we’re always fighting. Like, in it you seem to be getting mad at me about every other page. I don’t remember you ever doing that.”

I looked at her in surprise.

Then she wrinkled her nose and grinned conspiratorially. “Are you just spicing it up, like? So they’ll want to publish it?”

My jaw dropped.

“I mean, I don’t mind at all. It’s a terribly good story. And, like, it’s brilliant, thinking of myself as a character in a book.”

“But, Sheila, we did fight. We fought all the time. When you came into my class, you—”

Again she turned to look out of the window. Silence ensued and it lasted several moments.

“What exactly do you recall?” I asked at last.

“Like I said …” And then she didn’t say. She was still gazing out of the window and the words just seemed to fade away. A minute or more passed.

“We did fight,” I said softly. “Everybody fights, whatever the relationship, however good it might be. It wouldn’t be a relationship otherwise, because two separate people are coming together. Friction is a natural part of that.”

No response.

“Besides,” I said and grinned, “I was a teacher. What would you expect?”

“Yeah, well,” she said, “I don’t really remember.”

I couldn’t come to terms with the fact Sheila had forgotten so much. Driving home on the freeway that evening, I turned it over and over in my mind. How could she forget Anton and Whitney? How could the whole experience be reduced to nothing more than a fond recollection of colorful plastic toys? This hurt me. It had been such a significant experience for me that I had assumed it had been at least as significant for her. In fact, I had assumed it was probably more significant. Without me, that class, those five months, Sheila most likely would now be on the back ward of some state hospital. I had made a difference. At least that’s what I’d been telling myself. My cheeks began to burn hot, even in the privacy of my car, as I realized the gross arrogance of my assumption. I was further humbled by the insight that those five months might well now mean more to me than to her.

She had been only a very young child. Was I being unrealistic in expecting her to remember much? At the time she had been so exquisitely articulate that it had given her the gloss of a maturity even then I knew she didn’t really have, but I had been accustomed to associating verbal ability with good memory.

As I sped through the darkness, I tried to recollect being six myself. I could bring to mind the names of some of the children in my first-grade class, but mostly it was incidents I could recall. There were a lot of small snippets: a moment lining up for recess, a classmate vomiting into the trash can, a fight over the swings, a feeling of pride because I drew good trees. They weren’t very complete recollections, but if I tried, I could identify the locations and the names and appearance of the individuals involved. Still, they were nothing akin to the clarity of my memories as an adult. I was probably being unrealistic in expecting her to remember more.

Yet, it nagged at me. Sheila wasn’t just any child, but a highly gifted girl who had blown the top right off almost every IQ test the school psychologist had given her that year. Sheila’s prodigious memory had been among the most notable of many outstanding characteristics. She had used it like a crystal ball for gazing in, as she spoke to us all so poignantly, so eloquently of love and hate and rejection.

Love and hate and rejection. It couldn’t be all arrogance on my part to expect that she should be remembering more. Her amnesia seemed so uncharacteristic, but still, it was not hard to imagine what might be causing it. Although I didn’t know any specifics about what had happened since Sheila had left my room, I knew these hadn’t been easy years in between. She had been in and out of foster homes, had moved to different schools and coped with her father’s instability. If these years only half mirrored the nightmare she had been living when she’d come into my class, they would have given her ample reason for forgetting. She’d been such a brave little fighter that I didn’t like to think she had finally buckled under the strain, but in the back of my mind, that’s what I was beginning to accept. Yet … why had she so thoroughly forgotten our class? The one bright spot, the one haven where she had been loved and regarded so well? Why had she forgotten us?