Читать книгу Interrupted by God - Tracey Lind - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Preface

ОглавлениеCome to the edge.

We might fall.

Come to the edge.

It’s too high!

Come to the edge!

And they came

And he pushed

And they flew.1

—Christopher Logue

The English poet Christopher Logue aptly describes what happened to me one cold January day in a McDonald’s restaurant on Forty-second Street in New York City. I was interrupted by an unfamiliar voice that called out to me from within the depths of my soul. It probed and prodded, provoked and persuaded, pulled and pushed at all that I was and all that I hoped I would become. “Come to the edge,” the voice said. “No, I am afraid.” “Come to edge,” it insisted. So I went to the edge. The voice pushed, I flew, and I’ve been soaring ever since.

As an Episcopal priest and dean of a major urban cathedral, I live at the center of an established church and privileged society. Yet in my very being, as a child of an interfaith marriage, a lesbian, and one who has spent a great deal of time with the homeless, I belong to the edge, to the fringe, to the people who are never certain if, when, or where they fit into the great scheme of things. Staying close to the edge, I see all kinds of things that I couldn’t see if I only lived in the center of safety and privilege.

A journalist once asked me what it is like to live with “double vision.” As a person who lives in the center but is drawn to the borderlands and boundary waters of the margins, I see the truth of life in various shades of grey. There is no black and white. Nothing is absolute, and there is always opportunity for something new to emerge in both the darkness and the light. As St. Paul, a spiritual ancestor whose life and vocation was also interrupted from the edge, once said, “Now I know only in part; then I will know fully, even as I have been fully known” (1 Cor. 13:12).

Over the years, I have learned to claim the edgy religious, sexual, social, economic, and political paradoxes of my existence and of those whom I have encountered in my daily life and ministry. As a person of faith, I have searched for the good news and truth within those paradoxes. This book is an attempt to speak honestly about the paradoxes that call me from the center to the edge and back again.

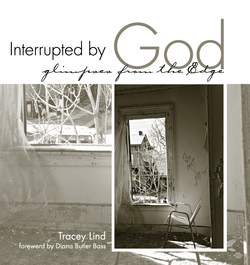

The stories and photos I’ve included here illuminate gospel truths and divine revelations from my perspective on the edge of exclusion and embrace. In the introductory chapter, I explore the question of passing or dying for my faith, of claiming or denying the essence of myself. This question, asked of me over three decades ago, was my first interruption from God, and the search for its answer has afforded me frequent glimpses of God from the edge.

In the chapters that follow, I introduce you to Lisa, the homeless Christmas angel; Siah, the infant hope of her ancestors; Mike, the child who understands the wisdom of the wind; Sally who feasts on communion remnants; the Garbage Tree on Ellison Street; Yvonne, the Good Friday interruption; Bacardi, the drunken Christ; and the sisters of mercy who beckon us to the banquet—all of them interruptions of the holy. I explore my desire to light up the world, why I do ashes, how I pray for peace, and the power of a five-dollar bill. I invite you to embrace the darkness, encounter the demolition contractor, remember the power of baptism, climb mountains, cross the great water, love the fallen flower, and keep on singing. I unabashedly describe myself as an Evangelical Universalist who claims Jesus as my way, finds life in the Trinity of love, but believes that the journey with Christ is not the only saving truth. In the closing chapter, I describe what I understand to be the essence of the Gospel in the children’s game of hide-and-go-seek.

In an article for The Witness Magazine, newspaper columnist Ina Hughes wrote, “It is not by accident that all great teachers of every religion used stories to get their message across. You can preach me a sermon, show me a doctrine, recite me a creed—and I might be impressed. But tell me a story, and I will remember.”2 I have been blessed with the gift of many stories. A few of my stories are out of the imagination of my heart and head, but most of them are true stories from real life, usually from intrusions into my daily routine.

A number of years ago, I picked up a camera and went looking for God in my neighborhood. Through my camera lens, I discovered a spiritual discipline for myself. Photography is not my profession, nor is it my hobby. Rather, the making of photographs is for me a form of prayer and meditation. As a raging extrovert, I am usually actively engaged in the world around me. Photography is a way that I distance myself enough to see what is happening. When I examine life through the eye of a camera, I am forced to step back, slow down, concentrate, and become deeply attentive to the situation. Looking through my viewfinder, I can’t allow myself to focus on simply what lies in the middle of the frame; I must explore the circumference, the corners, and the edges in order to really see the entire situation.

As one who moves quickly, the art of photography does not come naturally to me. I must work at it. But I have discerned that photography is the work of my soul, not my ego, and I have learned the hard way that whenever my ego gets involved, it distorts the picture. Photography keeps me humble and often frustrated, but is an important metaphor for the rest of my life. Photography has taught me to slow down, wait for the moment, and open myself up to the Spirit so that I may experience God in unexpected people and places.

Over the years, I have discovered that I can look for and find glimpses of the Holy through a camera lens, but I must be very respectful of what is found and seen. I don’t “take shots” and I don’t “capture the moment.” Rather, I enter into sacred relationship with the other, and with respect and permission I make a portrait of what I see, and then I pray that my photograph will honor the essence of what my eye saw.

I have been amazed and awestruck by what I’ve seen and heard, and I have tried to be faithful in the rendering and interpretation. In working on this book, I have become convinced that if we allow them, the poor can be our wisest teachers, the wounded can be our most powerful healers, and the oppressed can be our strongest liberators. I now know for certain that the last can be first, the despised can be loved, the outcast can be welcomed, the dead can be raised, and that which the world deems to be garbage can be made holy if we are open to the unexpected grace of God.

Interrupted by God has long been in the making and would not have been possible without the encouragement, love, and support of a great many people. I want to say thanks, and I ask you to accept my apologies for this long list of names and to feel free to skip over these pages and get on to the introduction and the stories. But if you do, please know that I am nothing without these individuals.

I offer special thanks to those who took the time to read the very first draft of this book: Dan Schoonmaker, Angela Ifill, Robin Hitchcock, Richard Gildenmeister, and especially Jon Wakelyn, who told me to let it go and send it to the publisher. I am grateful to John Dominic Crossan, who looked at the photographs, read the first few pages, and whispered in my ear, “It’s a sacrament. Go for it!” I am most appreciative to Pamela Johnson for her editing, support, and inspiration. I thank Janice Brown and Robyn Henderson for photo editing, production, and design. To Michael Lawrence, Timothy Staveteig, and the rest of the team at The Pilgrim Press, thank you for having faith in my project and making this book a reality.

I am especially indebted to my teachers over the years. I will never forget Janet Raleigh Smith, who in high school shared with me the love of books, music, and art, and encouraged me to ask hard questions and not accept easy answers. I offer special thanks to Phyllis Trible, Dorothee Soelle, Carter Heyward, Walter Brueggeman, James Forbes, Marcus Borg, James Cone, Raymond Brown, Ardith Hayes, Paul Henry, and Marge Lotspeich—scholars who before, during, and after my years in graduate school and seminary encouraged me to think critically and out-of-the-box.

I am ever thankful for some wonderful bishops I have known, admired, and loved in the Episcopal Church. To Paul Moore, who told me on the morning of my ordination, “All you have to do is love them.” To Jack Spong, who challenges the church, encourages its scholarship, expects excellence from its clergy, and said to this young priest, “If you wait for a sabbatical to write, it will never happen. You have to get up every morning and do it.” To Jane Holmes Dixon, who has shown me the power of passionate truth telling in the name of gospel justice. To Clark Grew, Arthur Williams, and David Bowman, with whom I have shared ministry in the Diocese of Ohio. And to Richard Shimpfky, who taught me how to be a priest and still loves me unconditionally.

I am grateful to some remarkable ecumenical and interfaith colleagues. Doug Fromm advised me to “dance at their weddings and cry at their funerals.” Joan Brown Campbell invited me to the summer pulpit of the Chautauqua Institution, thus opening new doors and avenues for preaching. Arthur Waskow helped me understand the sacred significance of the fringe, and Howard Ruben welcomed me home.

I have been blessed with many friends and companions along the journey. I offer special thanks to the Women’s Sewing Circle for friendship, laughter, and support; and to the Gang of Four for wit, wisdom, and wisecracks. I will always be indebted to Diana Beach for patient listening, deep digging, and wise counsel over the course of two decades. The photographs in this book would not have been possible without Clelia Belgrado, Doug Beasley, Meg Meyers, and Jennifer Jones, who taught me how to see through the lens of a camera. I am grateful to Nancy and Bill Dailey for schooling me in the art of radical hospitality, to Joe Russell for the gift of storytelling, and to Jane Russell for teaching me about long-term loving. Special thanks go to my cathedral colleagues: Greg, Tina, Kurt, Joyce, Dan, Mike, Marcia, Tricia, Rebecca, Rufus, James, Roderick, KG, Melonie, Ed, Rosemary, Twanna, Agnus, and Joanne for being a great staff team, ever patient with my foibles. I also count my blessings for Lucinda, my sermon and shopping buddy; Kathleen, Annamarie, Jamie, and Eric, who helped me say “yes” to God; Fran, who accompanied me on the way; Bob, who taught me to hug trees; Michael, who sang a new church with me; Wiley, who introduced me to Village Cleveland; Kate, who showed me her Chautauqua; and Karen and Tracey for being good pals. To the rest my friends and companions along the way—you know who you are—thanks for teaching me about life and love.

And who are we without family? Thanks to Kathleen for long walks in the cul-de-sacs; Tom and Jon for granting me the family memory; Jesse, Gillian, Jake, and Phillip—the next generation; Kathi for loving my brother; Missy and Bob for believing in me since I was a child; and Paul, Jean, Melanie, Margaret, Steve, and Anne for welcoming me into the Ingalls family.

And finally, this book and its author simply would not have been without my parents, Stanley and Winne Lind, who gave me the best they had to give; my “second mother” Marge Christie, who shares my love of church and beach; Emily Ingalls, my partner on the journey come hell or high water; and the people of Christ Church, Ridgewood, St. Paul’s Church, Paterson, and Trinity Cathedral, Cleveland, who over the past twenty years have shared their lives, loves, and losses with me.

This book is offered in love to those who are willing to receive it. I hope that this marriage of word and photograph will help you see glimpses of God with your own eyes and validate your own interruptions from the edge.

The Question | NEW YORK CITY, 1999