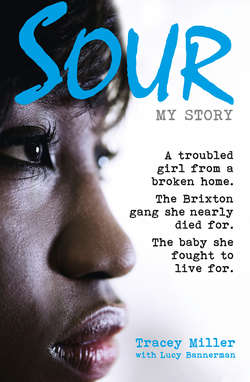

Читать книгу Sour: My Story: A troubled girl from a broken home. The Brixton gang she nearly died for. The baby she fought to live for. - Tracey Miller - Страница 10

Islam

ОглавлениеIslam and I didn’t get on. We were very young when Mum converted. By the time I got to primary school, Mum was no longer Eleanor Raynor. She was now Ruqqayah Anwar, Muslim convert. My brother Jermaine became Yusuf. My name became Salwa. Try saying that in a south London accent. That’s how Sour was born.

It was annoying at the time, but I hadn’t quite clocked, aged five, how useful two names can be when you get arrested. Later days, I’d thank my mum for it. Probably most useful thing she ever did. Get arrested, use one name; get arrested again, use the other. Keep getting arrested, just make ’em up. Boydem work it out eventually, but it buys you time.

Mum had been in one of her rare calm moods when she met the man on the bench.

She said she liked his aura. “Di man looked pious.”

He was slim and well-kempt. He said he’d show her a different way of life. So she thought she would give him a try.

Do you know how easy it is to convert to Islam? All you need is a front room, two witnesses, an imam and a few sentences and that’s it, you’re a Muslim. Eleanor Raynor was no more.

Now she was Ruqquyah, the pious. She hadn’t been the best Christian, granted. But God’s loss, Allah’s gain.

My brother and I watched from the hallway. He was giggling. I’d soon find out he had plenty to laugh about as a boy. I would be the one who suddenly had all the restrictions. No, as I say, me and Islam were not going to be friends.

Mum didn’t like covering her hair at first either. A wash before prayer, the rules about meat, all those things threw her off at first but she got used to it. She still allowed us to be kids and watch TV and listen to music.

I liked her in her white jilbab though. Better than some of the other outfits she used to wear. I thought she looked beautiful.

I didn’t even mind the mosque, at first. We went to Brixton Mosque. It was one of the oldest in South London. Got a bit of attention later days, when it was reported that that beardy lunatic, Richard Reid – remember him? The Shoe-Bomber? – had attended, but I liked it.

It had a quiet, happy vibe. It was somewhere to breathe beyond Roupell Park. Instead of being indoors, sitting all alone, Mum met all these new Muslim characters. They looked peaceful.

They would cook a lot together. I must say Mum looked at her happiest in the early days of Islam.

When they came round to the house, it had to be segregated. Men downstairs, women upstairs, no cross mixing. Even dinner would be brought separately.

That was the bit I hated the most. I didn’t like being apart from Yusuf. It wasn’t as much fun.

Thankfully, the Saturday madrasa was still communal.

We had to learn the Qur’an. It was lots of recitation, mainly. It sounded like a song. And so much memorising! We’d memorise whole chunks, reciting them over and over again without understanding what we were saying.

We learned the Arabic alphabet. We chanted the days of the week. Once you’ve got the alphabet, you see, what changes the sounds and meaning are the apostrophe and symbols.

I learned Arabic words for things like table, chair, but did I understand the meaty bits? No way.

Still, I picked it up quicker than Yusuf.

“We speak English, innit? What we having to learn this for?”

“C’mon, we’ve got to do what Mum said. It ain’t that bad.”

“But it’s just squiggles and dots.”

“What you complaining for? You don’t have to dress like some ninja. I’m the one who’s got to wear this.”

He looked at the headscarf framing my miserable face.

“You look bare nice,” he said, and burst out laughing.

Whatever Mum put on my bloody head for the mosque, it was horrible. I felt like a misfit on the bus. I wanted the ground to swallow me up. My friends used to tease me.

“What you got tucked under there, Sour? Is you a Rasta without the locks?”

Once I got to secondary school, Mum and I did a deal.

“Listen and listen to me good,” I said. “I ain’t wearing this headscarf shit no more.”

She started to protest.

“I ain’t playing, Mum.”

If she shouted, I shouted louder.

Eventually, she agreed on a compromise.

She bought a hat. It was like something the fucking queen mum would wear. It was brown and rectangular – with a brooch. I looked like a bat-shit crazy old Jamaican lady! Those early bus journeys did little for my brand-name, tell you that much. I was so upset.

Still, somehow I felt less guilty taking off the hat and leaving in the locker, than I did with the headscarf.

But there was no escaping the rest of my new “Islam-friendly” school uniform: MC Hammer trousers, brown sandals and an atrocious top. Lord have mercy, these clothes were taking the piss.

Although I was glad to see my mum happy, something didn’t sit well with me and her new obsession. There were other Jamaican families going to the mosque too. A surprising amount. But it felt oppressive. I was being forced to conform to a society that I didn’t understand, being forced to memorise words whose meaning I didn’t know. I hated the way Islam treated girls. I hated Mum for making me go, and eventually, for all its peaceful atmosphere, I began to hate that mosque. I knew as soon as I was old and strong enough, I would be outta there before you could say Insh’allah.

With Islam came stepdads. Yasim looked like frigging Moses, man. He walked with a big, old stick and smelled like a prophet. He was strong, strict and – like most people in our household – didn’t last long.

He had a strong emaan and he was strong in his faith. He was a nice guy deep down. Had a bit of a lisp. He was ginger and freckled, but of Caribbean descent. He remains the only man I’ve ever known to wear leather socks.

He didn’t work. Nowadays, you’d probably call him “a house husband”. Or maybe just “chronically unemployed”. But it was a home life, of sorts. It used to upset him that because of Mum’s unstable behaviour she couldn’t hold down a job. Never understood what his excuse was.

He tried to get me to go to school wearing a scarf again, but he realised pretty quick it was going to be a struggle making a family like ours stick to any rules, let alone his strict Islamic ones.

It wasn’t that we set out, deliberately, to get rid of him … Not exactly.

He wound Mum up too. When they got in an argument, she would pick up a baseball bat or go rifling through the knife drawer, just like she did when she was in one of her manic states and she caught wind of the fact they were coming to take her away again.

During one of her psychotic episodes, that kitchen drawer was always the first thing she went for.

Oh yeah, Muslim or not, my mum was a violent cookie. All the crazy demonic behaviours, I learned from her. I learned from an early age how quickly people scatter when you’re waving around a bread knife.

Poor Yasim was terrified. It must have been a relief to piss off to the mosque five times a day.

“We got to get rid of him, Sour,” whinged Yusuf one day after madrasa. “He won’t let me go to football no more.”

I agreed.

When we got home, Yasim was at the end of his tether, shouting to be heard over Mum’s music.

“Ruqqayah, these kids need discipline. They are a disgrace!”

“You’re not our dad,” we shouted after him. “Fuck off.”

The next week my brother and I came home to find the front room empty. His shoes were gone from the hallway.

“Where is he?”

“He’s been and gone,” Mum replied. “Me couldn’t take him nuh more. If rassclat make me choose between my pickney and him, di kids dem, dey haffi win every time.”

I was proud of her that day. But she could never be alone for long.

The first time we saw Derek he was fixing one of the curtain poles in the front room. “Alright, kids?” he said, noting our bewildered expressions. “Said to your mum I’d keep an eye on the place.” He seemed like a cool guy so we didn’t mind him helping himself to drinks in the fridge.

I noticed the spare house keys in his hand. Mum had been in and out of hospital. She must have asked him to come and check on us.

I recognised him. He lived in the same block. I’d seen him chatting to Mum on the stairwell a few times.

When Mum left hospital, she seemed happy – better than she had been in a long time. Derek soon started coming round the house a lot. He wasn’t strict like Yasim. He was like a breath of fresh air.

And yet, there was something about him I didn’t like. No reason. He just felt too familiar, too tactile. I’d catch him fixating on himself in the mirror, rearranging what was left of his sandy blond hair to cover a receding hairline.

I started wondering what was wrong with his flat. I think he had kids, grown-up ones, but if he did he never mentioned them. Soon he became a regular feature on the sofa.

Said his TV was on the blink, so Mum let him use ours to watch his endless hours of Formula One. That man could watch cars race around a track for hours.

I started focusing on him a little more closely.

Mum thought he was a kindly neighbour. I thought different.

He started taking liberties.

He used to draw penis pictures on Mum’s photographs. That’s it, I thought. He’s done it now. She’s got to realise this man’s an idiot soon. Instead, she walked in, saw the pictures and laughed. She found it comical.

Wasn’t long before he started trying to brush my thigh as we watched telly on the sofa, and began flashing himself at me on the landing as he came out of the bathroom.

Pretended his white robe just accidently fell open, to reveal his erection. In which case, why did he stick out his tongue at me at the same time? I would act like I didn’t see it and jump back to my bedroom, but my blood was boiling. How dare he come into my house and try to humiliate me!

He never physically touched me, not really, never anything more than a careful brush of the thigh, or pressing a little too close when we passed in the hallway. I didn’t say a word.

Althea might have moved out, but she still visited from time to time.

One evening, I passed her old room. The door was open just wide enough to see her comforting someone I recognised. It was her best friend, Suzanne. Suzanne’s cousin was the father to Althea’s little girl. She was crying.

I hung behind the door, and strained to listen.

“You need to tell my mum,” Althea was saying.

Suzanne was shaking her head, and wiped her nose with a tissue.

“No, I can’t. What am I going to say?”

“Just tell her the truth.”

She shook her head again.

“I knew I shouldn’t have told you. It’ll cause too many problems.”

I listened closer. Suzanne had met Derek a few times. They had exchanged a few words when she came up with Althea, that sort of thing. Later, he’d seen her at the bus stop and stopped to talk. She’s a chatty girl, Suzanne, thought nothing of it. It was only when he got on the bus too, she started feeling awkward. He hadn’t looked like he was waiting for the bus.

There weren’t many people sitting upstairs. Suzanne nodded a polite goodbye and went to sit at the back. He followed her. Sat down right beside her, even though the top deck was practically empty.

He started rubbing one hand up her leg as they approached the Elephant and Castle, feeling himself with the other.

“What you doing?”

“I see how you dress. I know what girls like you want.”

“Get your hands off of me,” she said, louder this time.

But he squeezed her leg tighter. Ragged fingernails laddered her tights. His other arm was hammering up and down like a piston. Hers was the next stop.

Suzanne missed her stop that night, and a few stops after that.

“I told him I’d tell your mum. He just called me a slag, and said she wouldn’t believe me.”

I went to my room that night, knowing I had to be prepared. I didn’t want my mum to go to prison. If I told her what he had done, to me or to Suzanne, she might just kill him.

I’d seen her physically attack him once already. We’d cheered her on, as she tried to strangle him on the sofa. “Yeah Mum, kill that fucker!” before it occurred that she might just do that, and we’d end up living with some bat-shit crazy lady like Ivy again. It had been against every natural instinct to pull her off him.

But now, things were different. If he’s that brazen, to do that to a family friend on the Number 133, what could he do to me? I sneaked down to the kitchen, slid open the drawer, and picked a knife. My hand hovered over the meat cleaver – nah, too big – then lingered by the bread knife. That’ll do. I slipped it up my sleeve and crept back up to my room, making sure the door was locked.

Then I slipped the knife under my pillow. I needed to get mentally prepared. I needed to defend myself.

That’s when I started sneaking the knives from the kitchen drawer. That’s when I realised I needed protection. Forget your knife at your peril.