Читать книгу Brutal Legacy - Tracy Going - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Five

ОглавлениеBrits was built on the back of the motor-manufacturing industry, sweating miners, subsidised farmers and staunch Afrikaner politics. It was in fact just outside Brits, at the nearby De Wildt railway station, that the heart of the National Party first beat following a speech by General Barry Hertzog in 1912. It was a town proud of its heritage and, as cultural purity reigned, it comfortably gave prominence to those more radical in their views.

Dries Alberts lived near the Hartbeespoort Dam, where when the sluices opened the waters rushed to nourish the surrounding farmlands. It was here that the wheelchair-bound chief of publicity for the Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging (AWB) spewed his propaganda. As a committed supporter of separate development, it was reported, he insisted on only the purest Afrikaans being spoken in his home. It seemed a great irony that he inflicted an English education on his hapless daughter and that we would eventually attend the same school. I remember her as an achingly shy young woman with big, burnt-umber eyes that opened wide as though always startled, and a caring, gentle smile. Her long plait fell like a twisted rope, well past her broadened hips, and hung heavy, a constant reminder that she was desperately out of her cultural depth.

Then closer to Brits, a stone’s throw from where we lived, was the stalwart and former wrestler Manie Maritz. In the late afternoons, he would grandly traverse his land, sitting straight and tall on his horse as he admired his Brahman cattle grazing nonchalantly in the veld, the entire herd completely oblivious to his supremacy. His rifle was always firmly lodged at his side as he patrolled his perimeter fence. A formidable force in khaki. The only hint of colour to break my memory was the insignia, the three black sevens that formed a triskelion in a white circle, conspicuous on a red background and worn openly on his sleeve.

But Brits was founded nearly seventy years before we arrived and we got there to find it leaning out of the shadows of its very modest railway-station beginnings. The town had risen out of the dust as businesses started up on the southern side of the train lines, on a road called Tom Street. Those businesses had since relocated north, across the line, and when I first knew Tom Street the scent of fresh Indian spices masked the dank smell of empty buildings and the richness of ground roots and desiccated bark filled the air. Shops opened onto the street, loud music beckoned, smiling faces greeted and owners and their sons lilted, “Good price. Good price.”

“Excellent price.”

“No worries, my cousin over the road will have your size. Let me call him.”

“Cheap-cheap.”

It was a street filled with special spices, sumptuous silks and bargain-basement buys.

The formal sector, where the more earnest business was done, had evolved over the years and Brits central was a sprawl of single-storey buildings that stretched from Spoorweg Street to the Town Hall. There the colour of saris was replaced by khaki, veldskoens and crimplene. Only lawyers, teachers and politicians wore suits, ties, long socks or pantyhose in that heat.

Ou Kasie, marginalised on the outskirts of town and hidden from view over the hill, was where resilience reigned and the burgeoning black community resided.

We all had our place in the sun, somewhere between God and the community, and there was no need for anything beyond. If someone died, everyone cared. If you got lost, then you’d be found. If you did well at school, the Brits Pos reported on it. It was a place where open secrets were shared and where dark secrets festered.

The author Brenna Yovanoff once wrote that the simple truth of a town is that you can know and love and hate it or even blame it and resent it, but nothing will change it – and that, ultimately, you’re just another part of it.

We were just another part of Brits.

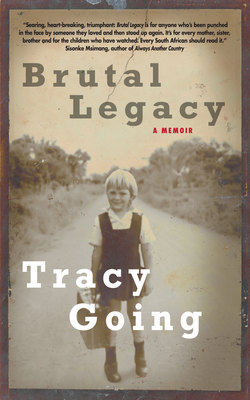

We had been there just on two months when I started Grade 1 at the local primary school, Laerskool Brits. We woke up really early that morning. My mother buttoned me up in my new yellow shirt and then pulled the square-necked, green dress with its firm flounce over my protesting head before getting the twins ready for their first day at the adjacent kleuterskool. When I climbed out of the car I pulled my short, green socks up long and high over my calves, trying to cover myself, all the while clutching my new cardboard suitcase. I walked in with it bumping against the back of my legs. My lunchbox and pencil case knocked around hollowly inside. I was just as hollow as I met Mrs Hickey and received the first of her daily hugs. Once all the parents had left, with lingering looks and the last of hugs, Mrs Hickey lined us all up and, holding hands, we snaked our way to the quad to stand together and sing for Volk en Vaderland. As the orange, white and blue flag was hoisted heavenward, our headmaster Mr Botha – said to be the nephew of the then Minister of Foreign Affairs, Pik Botha – placed his hand on his heart and led the way.

I was one of fourteen English-speaking pupils in Grade 1. It was an intake so large and so significant that the Brits Pos reported on it. The article went on to expound that had two additional students entered the system it would have warranted the appointment of another teacher, bringing the tally to five. But given that we fell short by two, nothing changed and it seemed four would have to do. The piece also announced my mother as a new teacher, but it failed to detail who she had replaced. It was an auspicious start to my school career.

The English-medium classes were separated from the main body, mostly into stuffy, prefabricated rooms where we were convinced we would choke and ultimately succumb to a torturous death of mesothelioma as we inhaled invisible asbestos filaments, either in the sweltering heat or with our knees knocking helplessly in the biting cold. It was here, sliced between the netball courts and the rugby veld overlooking the railway line and the silos, that we were schooled. It was an inconvenience not by design but rather from necessity as little provision had been made for the English arriving in Brits. The classes were so few in numbers that sometimes three grades would be taught in one class by a single teacher. My mother became one of those teachers.

My mother was a formally educated woman with a diploma in teaching. My father was not. He had fled boarding school in his penultimate year to never officially complete his education. But despite how qualified – and how respected – my mother was, and despite the long hours she sacrificed preparing, teaching and marking for three grades simultaneously, because she was not Afrikaans, it was necessary for her to reapply for her post annually. This uncertainty brought significant stress to our home, especially as my father’s need to seek oblivion in alcohol deepened and he became increasingly unreliable and unpredictable. And so it was that my mother’s level of education became a convenient and deliberate weapon of contention in the home.

Education and religion. Nothing more was required.

My mother being clever and her relationship with God. This was enough to unleash the rage.

Over the years it became a finely honed script. My father would come home late into the night, long after we were in bed. I would hear the argument start, then bear witness to its gradual and predictable escalation. My father belligerent, my mother pleading. As their voices rose, I would cup my ears closed, not wanting to hear, while I dug myself deeper into the bedding.

“You-shink-you-so-clever,” he’d slur.

“No, I’m not.”

“Yesh-you-are! Look’t-you – a know-it-all!” he’d shout.

“No, I don’t, I don’t know it all,” she’d beg. “Please. Please, Bruce, don’t. The children. The children are sleeping.”

It always started the same. Ended the same. The thumping. The pushing. The wrestling. Then the fists. Always the same. As I lay there with the air drawn from my bedroom, I would grab my blanket closer and place my thumb in my mouth, tears flushing my cheeks.

Afterwards, as the quietness pounded like the calm after a thunderstorm, I’d listen hard for the sound of her crying. When I heard it, I could take comfort knowing I hadn’t been abandoned and that my mother was still alive.

When I woke in the mornings my bed was wet and cold.

By the time I was washed and dressed, the overturned furniture was back in place and whatever had been destroyed set aside. We’d have breakfast and make our way to school, my mother taking special care to dress in order to hide her welts and bruises.

There were mornings that she didn’t manage to get to work at all, like the time my father cracked her head open with an empty Lion Lager bottle. By then we were already making use of the school bus so, after the early-morning ritual, she could return home to soak the blood from her matted hair and make her way back to bed to allow the hurts to heal.

Otherwise, as the day broke, she usually woke us up cheerfully and just as the weak rays of the sun melted the dew and the dank smell of moist sand tainted the air, we would clamber onto the bus for the lengthy journey through the farms of De Kroon to town. It was an old bus that rumbled along, detonating gravel rudely behind it. Each time it rolled to a stop to collect more scholars, clouds of dust would overtake us and our mouths would taste the grit as we stared out the window, our eyes still itchy from sleep. We always sat in the same place, behind the driver, in the front row. My brother, my sister and me next to each other, blonde and blue-eyed. Invariably, much bullying, shoving and pushing happened behind us, especially between the high-school boys, but the three of us sat there immune, safe, untouched and seemingly protected. We were English. And our mother, after all, was a teacher at the school.

But all privilege immediately dissolved when we were dropped off in the afternoons and made our way home along the dirt road. To break the tedium of our kilometre walk it sometimes became a game of neighbours pitted against neighbours and then we’d all gleefully and viciously participate in our very own post-Boer War flare-ups.

And this was just the place to do it, right here in the foothills of the Magaliesberg, deep in the valley of Silkaatsnek, where Generaal Koos de la Rey had played his hand and where the British Colonel Frederick Roberts had raised a white flag in defeat on that eleventh day of July 1900.

As our neighbours, the Badenhorsts, celebrated that long-ago victory, we took up the cause for Colonel Roberts and unreservedly fought back with stones that were thrown to almost miss and insults that were not fully understood.

“Engelsman!” they shouted.

“Dutchmen!” we hollered.

“Jy’s ’n rooinek. ’n Soutie.”

“You’re a plank. A houdkop.”

It made for an exhilarating journey home.

Other days were less eventful. Then we strolled along together, talking, laughing and kicking at the dirt. Some afternoons we stopped to pat the cows. Mostly, the cows ignored us and it became a competition of who could lure a brave one through the fence first and then stand still long enough as it enveloped a hand and an arm with its long tongue like a sandpaper tentacle all wet, sticky and slobbery.

But, together, we always looked out for snakes and we never fought on weekends and definitely not during school holidays.

Then we were steadfast friends.