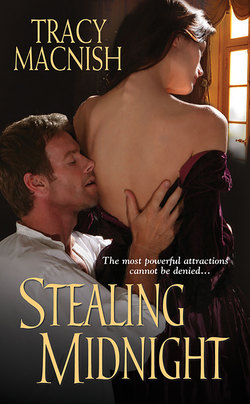

Читать книгу Stealing Midnight - Tracy MacNish - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter One

ОглавлениеChester, England, 1806

The night air fell damp and misty around the graveyard, and a filmy, chilled fog crept across mounded graves and silent crypts.

The night watchman took his bribe and left. Twenty minutes, he warned. No longer.

They would need every second, and so moved quickly—dirty fingers feeling around a freshly sealed tomb, seeking a crevice in which to insert a pry bar. The rusty metal bar groaned between the stone walls and iron door as chunks of crumbling lead came raining down from the broken seals. The lock gave way with a metallic crunch.

The men pulled hard, and beneath their efforts the door gave way. It slid open slowly, releasing a waft of stagnant, fetid air redolent of fresh rot and putrid remains.

A rasp of flint, a spark of light. A tiny, flickering flame revealed two male bodies, one a few days dead, bloated, stiff, and gray, the other lain on a slab of stone only that morning, unearthly pale and still.

The snatchers stripped the bodies before they bagged them in burlap sacks, grunting with their efforts, oblivious to the stench. Well into the stages of decomposition, the older corpse would only bring half the price, but at three months their regular salary, was still well worth the risks. The fresh one, however, would pay double, and was the one for who they’d come.

The specimen was grand: a young male aged approximately thirty years, his body well-muscled and devoid of wounds.

A muffled bell tolled twice in warning. The snatchers tossed the bagged bodies over their shoulders and put out their light. Disappearing into the darkness, they hurried down the rolling hills to where their cart sat hidden in a dark grove of pine trees.

With rags bound to their horses’ feet to muffle their sound, they drove their macabre bounty across the countryside, leaving the walled city of Chester behind them as they made their way to the River Dee.

Amidst whistles and tugs they urged the horses to pull the wagon onto the small barge, and once aboard, they set about securing the wheels with thick ropes. With a small splash and the lapping of water against a battered hull, they rowed west across the river and crossed the boundary into Wales.

Once on the other side, they drove the wagon on a narrow trail that led through the valley of two craggy mountains. Small dots of yellow lights could be seen in the distance: the village of Penarlâg.

They kept going, past dark, misty sheep fields and lichen-coated stone walls. Just on the northern outskirts of the sleeping village rose the crumbling estate owned by Rhys Gawain.

Carrying the bodies around back, the snatchers dumped them at the doorstep. One reached for the dangling cord and rang the bell. They waited a long while before ringing again. For the bounty the corpses would bring, they would wait all night.

The door finally opened, revealing a sleep-tousled young woman. In the yellow light of the tallow lanterns, her gray eyes were translucent, her black hair an ebony cloud streaked with lightning. The villagers had long ago named her a witch, attributing her odd appearance to a pact made with Satan himself.

Olwyn Gawain raised a brow as she looked down on the heap, a fiercely mocking look that had the men taking a step back. “Two?”

“Aye,” one of the snatchers confirmed, kicking at one of the corpses with his booted toe. “The big ’un is fresh. Just put in this marnin’.”

“I’ll fetch your pay.” She left for only a moment, returning with a small leather sack. Handing it over, she said, “Come back in a fortnight if you can find a female.”

As the snatchers departed, they heard a noise that sounded like a laughing sob, fading like mist into the foggy, cold night. They looked at each other in the darkness, and without a word, hurried away.

The rotting dead was not nearly so frightening as a living witch.

Olwyn belted her wrapper tighter around her waist, the damp chill of the wee hours making her wish for a peat fire and hot spiced tea. But with the two bodies lying on the back step, she had no time for such luxuries. Rushing through the crumbling stone corridors and up the enclosed spiral stairs to the master’s chambers, Olwyn mentally prepared herself for what would come. She rapped soundly on her father’s oaken door.

And then, with her breath coming in quick, shallow gasps, she forced herself to calm, waiting with trepidation to discover which incarnation of her father would greet her.

A few moments passed before Rhys opened his door. Olwyn immediately noted he wore a relatively clean nightshirt, buttoned to his chin. His black, hawkish eyes shone clear and sharp beneath his bushy, dark brows. Relief swept through her apprehension.

She didn’t apologize for waking him; he would have been furious if she hadn’t. “We have a delivery. Two this time.”

“Two? Well then, we’ll be busy, won’t we, girl? Good, good,” Rhys said, and he rubbed his hands together against the cold. “Wake Drystan. I’ll get into my work clothes and meet you down there.”

Olwyn didn’t demur, even though her heart fell into the pit of her guts. She did as she was told, fetching Drystan by pounding on his door. As he was usually drunk on the nights he didn’t work, it took some doing to rouse him. When he answered, the stink of unwashed skin, greasy bed linens, and sulfurous belches hung in the air around him. At her word, he grunted, scratching at his crotch as he headed down the long corridor. As part of his duties, he would pull the bodies inside, strip them of their burlap sacks, and lay them out.

After he’d gone, Olwyn moved like a wraith through the ancient keep. The stone walls held the chill and dampness, her footsteps a hollow echo reaching into the dark corners untouched by tallow lanterns.

Reaching a small, curving staircase so narrow it only allowed for one person’s passage, Olwyn ascended to the tiny landing that led to her chambers. She withdrew her key from a cord around her neck, and unlocked and opened the door.

A grouping of three small rooms warmed by a central fireplace comprised Olwyn’s sanctuary. There were only three windows, tall, thin, and arched, their stained glass as ancient as memory. Those she left uncovered, leaving the red-gold light to spill in from dawn to dusk.

The room smelled of strong incense: amber and Tamil mint, sage and sandalwood, cardamom and ginger. She burned a tiny bit nightly, her one indulgence, necessary to chase away the nightmares. The scented smoke clung to the drapes and rugs, her hair and her clothes.

Olwyn closed and locked the door behind her, a matter of constant practice since Drystan began watching her with increased interest.

Alone in her chambers, she breathed a sigh of resignation. The task before her loomed with gristly promise. But someday, she promised herself, she would escape. She needed to believe that, or else succumb to insanity.

Over her door, the brass bell jangled. The bell had a long, thin cord that ran down to the lower levels, so that she was able to be summoned. The few servants they’d had before had long ago been dismissed, so it was Olwyn who was called to duty.

With a fleeting, impotent glare at the hated bell, Olwyn quickly dressed. For the task ahead she wore a simple, muslin sheath that was easily laundered, and topped it with two thick, woolen robes that had been washed so often they were soft and fringed with threads. To keep her hair from her eyes, she braided it into a thick twist that hung heavily down her back. She left on her knit stockings and pulled on thick boots made of lamb’s wool that laced to her knees. The dungeon floor held a chill that would quickly leech the warmth of the living.

Those who believed hell to be hot had never stepped into her father’s frigid nightmare.

Olwyn grabbed her throwing dagger and slid it into her belt, took her pistol, checked its priming, and tucked it in her waistband at the small of her back.

The bell rang again, this time five rapid tolls that smacked of irritation and manic obsession. And Olwyn had nothing further to delay her. The time to return to hell had come again.

“You take too long, girl,” Rhys muttered as Olwyn entered. He never looked up from the naked corpse in front of him, but waved his hand at the other. “Get started on that one. This one needs to be opened immediately. He’s only got another day or two left in him.”

Drystan had dragged the bodies down to what had once been a dungeon, located in the oldest part of the keep. It was now Rhys’s workroom, for the permeating coldness helped to keep the corpses fresher.

It still bore the feel and look of its original purpose, however. The stone walls and floor were dark with the perpetual seeping wetness of the underground. Torches and lanterns hung from iron spikes, their smoke a thick wreath against the ceiling, the smell of which did not disguise the stench of rancid blood and rotting flesh.

Iron bars separated a few tiny cells which were now filled with crude shelves that housed her father’s collection of organs and brains preserved in brine, the abnormal ones beside the normal, each showing various stages of depredation.

And high above them, an old iron cage was suspended from the ceiling. It had been used in years past for madmen, when the former lord of the land saw fit to restrain them.

It had also been used for Olwyn, one dark night when her escape had been thwarted. After the dogs had attacked her on the property border, her father had dragged her back and put her in the cage. A lesson, he’d said, for a girl who’d dare to abandon the last member of her family.

She tried to avoid looking at it. It held memories of the worst night of her life, wounded, afraid, and alone in the dark dungeon, with the rats.

Scuttling rodents kept to the shadows, fat, bold, and rapacious from feasting on the scattered bits of flesh that regularly fell to the floor.

Olwyn’s hand rode lightly on the hilt of her dagger. She could shoot a rat in the head at fifty paces, could hit it with her dagger at half that. The rats seemed to know it, too, skittering to the corners when she entered.

Lord, but she hated them. They plagued her nightmares, their long, naked tails dragging behind their slick, dark bodies as they wallowed in the chest cavities of the corpses.

She peered into the shadows where they waited. She could see their eyes glittering in the torchlight. A shiver took her and she stamped on the floor as she walked, hoping to frighten them further away. The effort remained futile, though. The rats were as brash as they were ugly.

Olwyn moved to the stone slab that held the other corpse, just as her father instructed. Tuning out the meaty sounds of Rhys’s work, she got to her own.

The body was male, aged between twenty-five to thirty years of age. He was well formed and well fed, healthily muscled, and looked as though he had been in vigorous, perfect health at the time of his demise. Her eyes swept over his naked body, taking in his details. A scar on his arm, a birthmark on his thigh, a thick thatch of dark bronze hair surrounding his long, flaccid penis.

If she ever found a man who did not fear her a witch or sorceress, at least she could go to his bed not fearing his nakedness. Rhys did not cover the sexual organs of the dead to preserve Olwyn’s innocence. His determination to figure out why the human body aged, succumbed to illness, and ultimately died consumed him. Everything else that concerned the living had become an extraneous detail to which he gave no notice.

The sound of grinding bones beneath a saw mingled with the grunts of her father’s labor.

Olwyn inwardly cringed and kept her eyes on the body before her. He had not been dead long, she thought. He’d not yet flattened on the bottom, and he had no signs of stiffness.

Sadness touched her heart, as it often did when the specimen had been cut down in their prime. Did a young widow weep for him at night, her bed empty and cold without him? Was his father holding his mother in comfort, even as he shed tears for his son? Did a small child sleep, dreaming of a father he would spend a lifetime trying to remember?

Olwyn’s gaze slid up and down the naked man’s body. Even in death he was handsome, with dark gold hair gleaming in a thick halo around a visage that when alive, must have been quite a sight to behold. He wore joy on his face, in smile brackets around his lips, and in thin lines stretching from the corners of his closed eyes.

And taking up her papers and charcoal, she was full of regret that she could not sketch him as such, a virile, vibrant man full of life and laughter.

Instead, she drew his body as it was, long and lean, a study in symmetry and masculine beauty. She worked fast, and as she did, she tuned out the noise behind her and focused on the man whose life had been cut so short.

Olwyn drew his hands, his sinewy arms, the bulge of muscle and elegant shape of his shoulders. She tried to capture his face, so still and beautiful in death, and a lump thickened her throat once again. Did he have sisters who mourned him? Brothers who longed for just one more day?

“Olwyn, look at this,” Rhys said, his voice brimming with excitement.

Obediently, Olwyn laid down her work and moved to the side of the partially dissected cadaver. Rhys had made a long incision down the center of the torso and across the chest and gut, allowing him to pull back thick flaps of flesh, fat, and muscle. The sawing she’d heard had been the removal of the front of the ribcage, leaving the organs exposed.

“Look, girl. See the liver. Look at his nose, bulbous, thick with veins. I’ve seen this correlation before. I’m onto something here.” Rhys lifted his head and his black eyes were lit with an urgent fervor that too closely resembled madness. “I need the liver of the other man for comparison. Drystan! Get my scales.” He sank his hand gently into the chest and palpated the heart, pausing to look back up to Olwyn as if he’d forgotten why she was there. “Are you finished your sketch?”

“Nearly. It will take about ten more minutes, Papa.” She’d learned to move quickly, but he expected the impossible.

“Fine. Wait. No. The other one can wait a moment. Come sketch the way the liver looks now, before I remove it, so I can refer to it later.” He rushed her by waving at her stack of blank paper. “Don’t you stand there, girl. Move, move. This carcass rots as you breathe.”

Olwyn snatched up a nub of charcoal and a fresh sheet of paper, and leaning it on a flat plank of wood, drew in detail the distended liver. As soon as she finished, her father grabbed it away from her and furiously added notes about the color and smell, the shape and thickened texture.

Rhys threw the paper at Olwyn and dug his hands into the corpse’s torso. Olwyn heard a sucking sound as her father pulled the liver out, and she swallowed hard against the rising bile in her throat. No amount of assisting her father numbed her to the revulsion.

As the liver was weighed, measured, and examined, Olwyn returned to drawing the other man.

She drew him lovingly, the plane of his flat, lightly furred belly, the rise of his muscled abdomen from his narrow hips. Soon enough his torso would be split wide, his organs pulled and placed into glass jars, his entrails dumped in a bucket. Olwyn shivered with disgust and regret combined. How sad his family would be to know their son’s body had been so violated.

Her cheeks burned as she drew his genitals. As her charcoal scratched against the paper, she envisioned his penis slit open and examined beneath a magnifying glass. She pushed the thought away and instead imagined him alive.

She saw him on horseback, racing over a rolling green field. Wind filled his dark gold hair and his eyes sparkled with pleasure.

Olwyn set aside her charcoal for just a second and brushed her fingertips over his cold face, tracing his closed eyes. His eyelashes were long and lay dark against his pale cheek. What color had shone from his soul? she wondered. She touched the square line of his jaw, the stiff brush of his stubbly beard feeling lifelike over his frigid skin.

A sudden urge to protect the man came over her. She wanted to cover his nakedness, defend him against her father’s knives and saws, and see him properly returned to rest. He did not deserve such a ghastly end.

But even as the thought occurred to her, Rhys came behind her, his wickedly sharp scalpel winking in the yellow lantern light.

There was nothing Olwyn could do to stop him; Rhys spent all their money on corpses. He would never consider not performing an exam on one, just because Olwyn didn’t want him violated in such way. Her needs and wants and desires had ceased to matter the day her brother had died. On that day, Rhys became a man obsessed in his search for the key to life, and the reason for death.

Servants had been dismissed, food was rationed, luxuries were denied. And her mother, Talfryn, had run away. She’d never come back, and not a trace of her was ever found.

Olwyn had been left with her father, trapped like a rat.

Rhys stepped up to the side of the body and looked over it carefully. He lifted the head, the hands, and the feet, examined every inch of the skin.

“Not a mark on him,” Rhys muttered. Without being told, Olwyn wrote down his words. “No visible wasting from sickness, no bruises or sign of injury. No physical mark indicating cause of death.”

Rhys glanced quickly at the timepiece. His stomach growled and he snapped his head around to Drystan. “Tea and eggs. A heel of bread, too.” And then he trained his black, shining eyes on the broad, muscular chest of the dead man before him. “Let’s get started, eh?”

Rhys palpated the chest and abdomen before taking his knife into his hand. Olwyn held her breath and silently said a prayer for the man’s family, that they would never know what became of their handsome son and his perfect body. She moved to the other side of the slab, and not caring if her father noticed, took the dead man’s hand in hers. It was solid and square and as cold as the crypt from which he’d been taken.

Could it be that she had been alone and desperate for so long that she was falling in love with a corpse?

In that moment, Olwyn knew she’d reached the lowest depth of despair, so pathetic that she’d come to crave the company of a dead man.

Tears burned the back of her eyes as Rhys slid the tip of his blade into the center of the chest.

And then they both gasped and froze in place as blood welled from the incision.

Corpses don’t bleed. Only a pumping, beating heart moves blood through a body.

Olwyn held her breath and looked at Rhys with huge, round eyes. “He’s alive,” she whispered.

Rhys pulled the knife back and watched the blood slowly leak scarlet across the dead man’s chest, visceral proof of life. He seemed to be in a trance, and when he brought his black eyes up to Olwyn’s, they glittered like obsidian.

“I need his liver,” Rhys said. He spoke with such flat determination that Olwyn’s blood ran cold. Her father pointed to the passage that led out of the dungeon with the dripping edge of his scalpel. “Go to your room, Olwyn.”