Читать книгу The Hopeful - Tracy O'Neill - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSESSION I.

YOU aren’t the first, but could be the last; I can only hope. My first was older and a man. He said it was all in my head, when he was the one always suggesting fantastical things. But now one year older, I’m the one starting over, and though I’d like to think his words drove me wrong, it was all my doing. Which is more than I can say of coming here. My mother signed the dotted line because they don’t need my consent. But, Doctor, my signature will matter in three weeks. You’ve read my file. Doyle comma Alivopro: an abbreviated Alis volat propiis in honor of my father’s alma mater. Alis volat propiis: in Latin, she flies with her own wings. Alis volat propiis: what a judge said of Oregon when still independent of Britain and the United States. No, Alivopro Doyle did not consent to be treated.

Can you pronounce that for me again? the doctor asks.

Ah as in apple. Leave, as in of absence. O like owe. Pro like the prefix before life.

And Miss Doyle, I’m sure you’re aware that though you may not have given your consent, our success here is mostly contingent upon your cooperation? And that though you may not be legally responsible for yourself, you are de facto?

Excellent use of dead language, Doctor, I say.

Now that I’ve stabilized—medical parlance for not much worse than normal— I’m required to answer for myself, my own argot for interrogation.

The doctor continues through the formalities, blocking off liabilities, begging the question. It wasn’t your choice, what we’re doing here, she says, and yet there must be reasons.

It’s better than college. But you’re referring, of course, to the threat I pose.

And that your signature will only matter to the law if you prove yourself capable of normative cognition? And that I will only be able to effectively evaluate your cognition if you cooperate?

Leverage: from the Latin levis, meaning light.

Do you understand, Miss Doyle?

I do. Just look at us, I think, the nervous couple, in our medical matrimony—because let’s not forget the brain is an organ—do you take this doctor to be your lawfully mandated psychologist? I do, I do, I must. And anyway, I’m no novice when it comes to this. Figure skating is the only mode irrational enough for a novice to be more advanced than an intermediate. Juvenile, Intermediate, Novice, Junior Senior, such is its progression of levels. So since the doctor is my second, perhaps I’m an intermediate. Between what, I don’t know.

You said that what you thought was all your doing. Can you give me an example of what you meant?

Another doctor wanting me to make an example of myself.

In the non-punitive sense, I assure you.

If I know anything at all, it’s that nothing can be assured.

Then shall we take a calculated risk? says the doctor. Shall we try? You have mentioned the threat you pose. Why don’t we start with what exactly it is you believe you pose? Why are you here, Miss Doyle?

And because I’m out of choices, except for one, I must begin.

I had a bus to catch in ten minutes and the only way I’d make it was with a pair of scissors. Before the accident, the first psychologist prescribed this and other visualization exercises for my success. There was one in which I imagined a red windmill turning blue with positivity and blowing away fear. In another a lung expanded to inhale confidence and contracted to exhale doubt. This one involved a hairy monster, which I was to confront with scissors and trim into a small, manageable form. It’s wonders what a new ‘do can do for a girl.

Catching the bus was never a problem until getting out of bed was, but you can’t make excuses. “Get out of bed. Get out of bed!” I told myself.

“Use the imperative!” is what Dr. Ogden had advised. “Affirmative statements only. If you say, ‘Don’t do this’ or ‘Don’t do that,’ you’re thinking about what you don’t want to do, not what you do.” Except when I listened to him, I mostly thought about the things I didn’t want that would happen if I said, “Don’t do this.” The problem with sports psychologists is that they have limited imaginations. It’s all if-then statements. If you practice, then you will be perfect. If you believe, then you will achieve! But if you accidentally think wrongly, then what?

This had been my problem with the triple Salchow. I kept watching myself fall. Or collide with the barrier of the rink. Or chicken out. Imagining got to be like death; I knew it would happen but not how. By the time Dr. Ogden got to if-then statements, I wouldn’t trust someone like me with my own wellbeing. And here’s another if-then statement: if I was still skating, then I would not have needed to try to get out of bed.

“How do you feel?” my father asked me the first time I skated.

“Greedy,” I said. It was true I could never get enough.

But now in bed I could hear the thin clock arm marking seconds populous and bland as rabbits— tick tock tick tock tick— and knew the difference between the rhythm of a metronome and a song. I tried to materialize scissors for the exercise but instead saw only a four-post bed. Sit! Roll over! Fetch! I commanded, but the mind is like most teenagers.

“If all the other kids were jumping off of bridges with underpants on their heads, should I too?” I used to ask my mother when she suggested that maybe I would rather go to school like other kids, see movies, eat cookies. This would be before most businesses were open and she’d be driving me to the rink. I would have woken her, scrambled egg whites, brushed my teeth. But that’s what days became: teeth brushing, tiny back and forths, up and downs, just to do it again. There are no decisive victories with dental hygiene—there is only not losing until a waitress forgets to hold the onions. And when I thought of not losing for the rest of my life, bed was just as good a place as any other.

That was no thought to get me up, of course. So for just a moment, I let my foot forget it was part of Middle America. I let myself lapse pastward, my foot pointing as it used to when my entire body pivoted around the axis of one toe, and I felt as I did when my life consisted of perfect circles, when it was all figure eights and laps around the rink. I closed my eyes and was back again, spinning on that slippery plane, and everything streaked together into ribbons of color so that I could not discern separate forms. But I knew where I was, where I was going. The ice, flatter and more perfect than the kind that forms in nature, revealed the path cut by my blades beneath me. I was flying without wings, contorting through the cold. My coach Lauren called out, “Arms! Arms!” and a Prince song about how he loved someone more than when she belonged to him played.

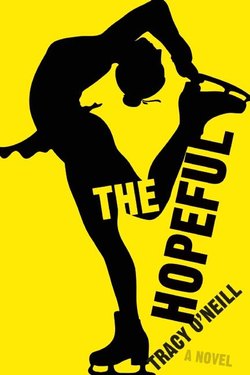

The music wasn’t my warm-up tape but Ryan’s, and we didn’t evaluate his choices because he was an Olympic shoo-in. A shoo-in is a mundane expression for someone whose victory seems predetermined. I wasn’t a shoo-in, but a hopeful, an eloquent expression for someone whose victory is yet to be determined.

Puberty could end my life, I knew. There were girls from the rink who were shoo-ins until bodily curves flattened their ability to jump faster than you can say circumference. I would not even look at bras in department stores, for the mind’s eye determines the future, as Dr. Ogden once said. I didn’t know how it happened. I was sixteen, and I was maybe getting too old. I made calculations: for the 2010 Olympics I’d be eighteen. In 2014 I’d be twenty-two, and no one skates in the Olympics at twenty-six. My year was only worth six minutes. Really only two and a half if I screwed up badly enough. I was training for the New England Regional Championships, the qualifying competition for the Eastern Sectional Champions, which was the qualifying competition for the National Championships. If I did well enough during the technical program portion of the competition, I would be allowed to skate my long program. But if not, then I wouldn’t even be permitted six minutes to not blow my year.

I read a jump lasts less than a second. There were four jumps in my technical program and ten in my long. Everyone knew all the judges cared about anymore were jumps, not like the days when centered spins and expressive arms could trump jumps. Not like the days when I would easily have been the best in the world. So really, less than fourteen seconds to justify that year. I practiced harder. Then harder. I kept a notebook of statistics. I woke up and thought, fifty out of fifty. I meant this for everything. On forty of fifty days, thirty-five of fifty days, I ran three extra miles, total: twelve. Fifty out of fifty it had to be. Six minutes for three hundred sixty-five days.

And of course I’d be a joke at the nationals without the triple Salchow. I’d thought I would have learned it by then, but time flies by incompetence, never waiting for excellence to catch up. And still, even with this knowledge, it was fun, though my mother doubted this when she saw me try to learn the jump. I fell for hours. It was the way I tried. I came home with bruises on my legs that blued and greened and yellowed every day I failed to perfect.

But I didn’t want comfort; I wanted rarity. “Think diamonds,” I used to tell my mother. “Supply and demand. That’s why the cost. And that’s why they’re worth it.”

“God help the man that falls for you,” she would say, seeing the violence of ambition bloom bruised beneath my skin.

Back then, I thought I would never lean on a person. I knew I could generate my own wind in still indoor air, cutting through the cold, rising and turning and falling alone. I could study forensically ice etchings: the circular storm of a well-centered spin, the clean cavity of a toe pick stab into a Lutz, the overt curve of a poor jump. In the hard tampered ice, I could read the history of chasing dreams.

Lauren skated over and we crouched by the evidence of my ineptitude. “You’re letting yourself go, that’s what this tells me,” she said. “You see the skid in this tracing? You’re letting your head get ahead of the rest of your body, and everything is following it in the wrong direction.”

“I’m sorry,” I said.

“Sorry means you won’t do it again. Are you really sorry? Show me sorry.”

So I skated the length of the rink with counter-clockwise crossovers to approach the jump, but I began to feel something happening, doubt or pounds perhaps. It was as though I knew that the most I would be able to do would be only not not doing it; it wasn’t simple math. Two negatives equal a positive, until you bring in the brain.

“You’re not even trying,” Lauren told me when I managed only two and a half rotations of the Salchow.

“I’m not not trying,” I said, and as soon as I said it, I didn’t know who had gotten into me.

“Not not trying is not going to land the jump for you,” Lauren said. “Do you know what I see you doing in the air?” She hunched, arms looped loosely as though cradling a heavy baby and right leg casually crossed over the other. “Now show me your air position.” I crossed my legs and pulled my arms mummy-like to the chest. “Tighter,” Lauren said. She put two fingers between my thighs. “Tighter,” she said. “Tighter, hurt me,” and I squeezed her between my legs until it hurt enough to be three rotations.

“That’s the position I need to see in the air,” she said. “If I hold my pinkie in front of my face when you jump, I don’t want to be able to see any of you poking out. No hips. No elbows. No knees. Nothing gets between those legs, do you understand? Nothing.”

“Nothing,” I nodded, and I knew when my ice session was over, I would have to take matters into my own hands.

“If you have small hands, then it’s easier to use a toothbrush,” Ryan told me in the boy’s locker room afterward. I needed to be taught or starve a little. “But if you haven’t accessorized for the occasion, just punch yourself in the stomach with the other hand.”

I hit hard with my left hand and reached with my right. “I can’t,” I said. “Nothing’s coming up.” My eyes blurred with salt, and my nose leaked. There were strands of throat beneath my fingernail. I looked up at him from the tiled floor, forearms braced to the toilet.

“Practice makes perfect,” he said. And of course he was right. You’ve got to believe a guy that can lose six pounds in three days with a round of amphetamines.

“Bulbous things don’t rotate well,” Ryan said, crossing his arms, and even as I reached inside again, I thought of planets, though I knew it was silly to think about a thing so big its shape cannot be seen by the eye, so big its arc appears flat, when the edge between perfection and everything else is smaller even than the eye can see. Just take the triple Salchow. It is hurtling from an eighth of an inch of steel into the air for less than a second, rotating three times, and landing one-footed on ice. It is swindling physics. It is knowing that a nudge of tilt, a movement glancing towards lateness is failure. It is birthing unnatural beauty. And this is for what Dr. Ogden had prescribed windmills. When I told him I was afraid of not having it, he told me you don’t have it until you do.

And this is what I thought of as I bent over the toilet. Again! Again! Again! I willed, though I had nothing much left in me to give up. Lauren’s words pounded once more— harder, harder— until I saw my eggs float coddled to the surface.

But when the next ice session began, I kept landing on two feet like a pedestrian. My legs were jelly, so I stood by the rink barrier willing myself to imagine red giving way to blue. When what I saw was purple, I tried to visualize lungs expanding and collapsing. On the clock I saw the seconds circling away. I skated the circumference of the rink. I stepped on my left foot and turned. I leapt and snapped tight to spin one two three, pointing my toe as gravity replaced me to earth. The ice rushed up into me, and there was no time to extricate my legs from each other. Horizontal on the cold surface, I saw shards of teeth globbed in blood melting luminous ice. One minute it had been windmills, the next I was not even a hopeful. I hadn’t not tried. Later the doctor who didn’t deal in affirmations told me I was lucky even to be able to walk.

“Some people lose their ability to interpret taste with neck trauma,” he said. “Fortunately, your nerves appear normal.”

“I don’t want to interpret pudding,” I said. “I want to skate.” But though I only wanted to skate, all anyone could do was talk to me about life, as though it wasn’t something I’d been doing for sixteen years.

“You have your entire life ahead of you,” my mother told me. “You’re young. You’ve never even been in love.”

I told her that you don’t need to make out with something to love it, and she informed me that anger is a critical step in the grieving process. She had been reading books about bereavement and terminal illness. There were chapters dedicated to consoling men who lose their testicles to cancer and discussing the afterlife with agnostics. Chapter one discussed Kubler Ross, chapter two denial. The chapter I wished my mother never read concerned building a support group, which made her rub my back and tell me I was not alone.

“That is exactly my fear,” I told her.

But when I returned to school, it was all sperm and eggs. There were slideshows with stillborns and women in labor. The school board thought the visuals would stop the inevitable. And I couldn’t stand to get out of bed to see these screaming women, to see how it happens every time.

So there I was that morning one year later, beneath sheets cradling myself in glimmers of leaping with hope and unnatural contortions and thinking again! Again! Again! and windmills until finally once I fell from my dream, once I felt once more that it was over, I knew I had to confront another day.

I looked at my clock, seven minutes left, and pulled down the covers. I closed my eyes again until I saw a monster. She sauntered long-legged over— tick tock tick tock tick—and I fumbled for scissors to cut her hair, hair thick and black and wild enough to get lost in, hair that resembled my own.

“You come here often?” she asked, and I didn’t respond.

“I know why you’re in bed. You must be tired, because you’ve been running through my brain all night.” She moved closer, raising her hand to touch the pillow behind my head, a dark, leaning figment, and breathed hot towards my ear until all I saw was a schism of cleavage. Two fingers teasing between my legs, two moving above the thighs—harder, harder until she said she knew I wanted it, she ate figure skaters for breakfast, and a pretty young thing like me didn’t belong in a place like this. Shears raised, I squeezed my knees and caught a glint of light reflecting in the sharpened edges. I squeezed tight through legs and fingers, closing my fist in a snip.

“There’s no one like me,” I said.

And then, I got out of bed.

I woke up in the hospital.